The Creation & Consolidation of the Irish Border

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary

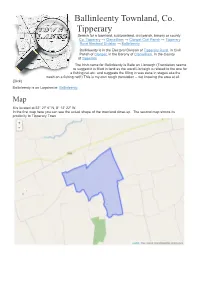

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary Search for a townland, subtownland, civil parish, barony or countySearch Co. Tipperary → Clanwilliam → Clonpet Civil Parish → Tipperary Rural Electoral Division → Ballinleenty Ballinleenty is in the Electoral Division of Tipperary Rural, in Civil Parish of Clonpet, in the Barony of Clanwilliam, in the County of Tipperary The Irish name for Ballinleenty is Baile an Líontaigh (Translation seems to suggest it is filled in land as the word Líontaigh is related to the one for a fishing net etc. and suggests the filling in was done in stages aka the mesh on a fishing net!!) This is my own rough translation – not knowing the area at all. (Dick) Ballinleenty is on Logainm.ie: Ballinleenty. Map It is located at 52° 27' 6" N, 8° 12' 22" W. In the first map here you can see the actual shape of the townland close-up. The second map shows its proximity to Tipperary Town Leaflet | Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors Area Ballinleenty has an area of: 1,513,049 m² / 151.30 hectares / 1.5130 km² 0.58 square miles 373.88 acres / 373 acres, 3 roods, 21 perches Nationwide, it is the 17764th largest townland that we know about Within Co. Tipperary, it is the 933rd largest townland Borders Ballinleenty borders the following other townlands: Ardavullane to the west Ardloman to the south Ballynahow to the west Breansha Beg to the east Clonpet to the east Gortagowlane to the north Killea to the south Lackantedane to the east Rathkea to the west Subtownlands We don't know about any subtownlands in Ballinleenty. -

Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to Be Crossed by the Proposed Project

Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to be Crossed by the Proposed Project TB No.: 1 Townlands: Abbotstown/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309268, 238784 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection TB No.: 2 Townlands: Dunsink/ Sheephill Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309327, 238835 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House (within the townland of Sheephill) and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). The remains of a stone demesne wall associated with Abbotstown are located along the northern side of the road (UBH 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection 32102902/EIAR/3B Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 TB No.: 3 Townlands: Sheephill/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 310153, 239339 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south. -

Town Tree Cover in Bridgend County Borough

1 Town Tree Cover in Bridgend County Borough Understanding canopy cover to better plan and manage our urban trees 2 Foreword Introducing a world-first for Wales is a great pleasure, particularly as it relates to greater knowledge about the hugely valuable woodland and tree resource in our towns and cities. We are the first country in the world to have undertaken a country-wide urban canopy cover survey. The resulting evidence base set out in this supplementary county specific study for Bridgend County Borough will help all of us - from community tree interest groups to urban planners and decision-makers in local Emyr Roberts Diane McCrea authorities and our national government - to understand what we need to do to safeguard this powerful and versatile natural asset. Trees are an essential component of our urban ecosystems, delivering a range of services to help sustain life, promote well-being, and support economic benefits. They make our towns and cities more attractive to live in - encouraging inward investment, improving the energy efficiency of buildings – as well as removing air borne pollutants and connecting people with nature. They can also mitigate the extremes of climate change, helping to reduce storm water run-off and the urban heat island. Natural Resources Wales is committed to working with colleagues in the Welsh Government and in public, third and private sector organisations throughout Wales, to build on this work and promote a strategic approach to managing our existing urban trees, and to planting more where they will -

Exploring the Economic Geography of Ireland1

Working Paper No. 271 December 2008 www.esri.ie Exploring the Economic Geography of Ireland1 Edgar Morgenroth Subsequently published as "Exploring the Economic Geography of Ireland", Journal of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland, Vol. 38, pp.42-73, (2008/2009). Abstract: Only a few research papers have analysed the spatial distribution of economic activity in Ireland. There are a number of reasons for this, not least the fact that comprehensive data on the location of economic activity by sector across all sectors has not been available at the highly disaggregated spatial level. This paper firstly establishes the geographic distribution of employment at the 2 digit NACE level, using a novel approach that utilises a special tabulation from the CSO 2006 Census of Population Place of Work Anonymised Records (POWCAR). It then analyses the spatial patterns of this distribution using maps and more formal methods such measures of spatial concentration and tests for spatial autocorrelation. The paper considers the locational preferences of individual sectors, the degree to which specific sectors agglomerate and co-agglomerate, and thus will uncover urbanisation effects and differences across urban and rural areas regarding economic activity. Keywords: Economic geography, employment distribution JEL Classification: R12, R14, R30. Corresponding Author: [email protected] 1 The author would like to thank the CSO, and particularly Gerry Walker, for making available the data used in the analysis. ESRI working papers represent un-refereed work-in-progress by members who are solely responsible for the content and any views expressed therein. Any comments on these papers will be welcome and should be sent to the author(s) by email. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote illustrations or maps Abbey Theatre 175 sovereignty 390 Abbot, Charles 28 as Taoiseach 388–9 abdication crisis 292 and Trimble 379, 409, 414 Aberdeen, Earl of 90 Aiken, Frank abortion debate 404 ceasefire 268–9 Academical Institutions (Ireland) Act 52 foreign policy 318–19 Adams, Gerry and Lemass 313 assassination attempt 396 and Lynch 325 and Collins 425 and McGilligan 304–5 elected 392 neutrality 299 and Hume 387–8, 392, 402–3, 407 reunification 298 and Lynch 425 WWII 349 and Paisley 421 air raids, Belfast 348, 349–50 St Andrews Agreement 421 aircraft industry 347 on Trimble 418 Aldous, Richard 414 Adams, W.F. 82 Alexandra, Queen 174 Aer Lingus 288 Aliens Act 292 Afghan War 114 All for Ireland League 157 Agar-Robartes, T.G. 163 Allen, Kieran 308–9, 313 Agence GénéraleCOPYRIGHTED pour la Défense de la Alliance MATERIAL Party 370, 416 Liberté Religieuse 57 All-Ireland Committee 147, 148 Agricultural Credit Act 280 Allister, Jim 422 agricultural exports 316 Alter, Peter 57 agricultural growth 323 American Civil War 93, 97–8 Agriculture and Technical Instruction, American note affair 300 Dept of 147 American War of Independence 93 Ahern, Bertie 413 Amnesty Association 95, 104–5, 108–9 and Paisley 419–20 Andrews, John 349, 350–1 resignation 412–13, 415 Anglesey, Marquis of 34 separated from wife 424 Anglicanism 4, 65–6, 169 Index 513 Anglo-American war 93 Ashbourne Purchase Act 133, 150 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1938) 294, 295–6 Ashe, Thomas 203 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985) Ashtown ambush 246 aftermath -

Register of Current Social Science Research in Ireland, 1988

ISBN 07070 0101 3 APRIL 1989 REGISTER OF CURRENT SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH IN IRELAND, 1988 Compiled by Florence O’Sullivan THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE REGISTER OF CURRENT SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH IN IRELAND, 1988 Complied by Florence O’Sullivan Copies may be obtained from The Economic. and Soczal Research Institute (Limited Company No. 18269) Registered Office: 4 BurlinEton Road, Dublin 4 Price IR£3.00 ~) The Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin. 1988 ISBN 0 7070 0102 3 This register, which is based on replies to a questionnaire sent out in March 1988, provides information on research in progress in Irish universities, colleges and other institutions. The Institute and the compiler gratefully acknowledge the help received from the contributor’s in submitting entries and thus making possible the publication of the register. Users are reminded that entries in the register are those provided by respondents and, hence, responsibility cannot be taken for the accuracy of the information presented. For further details of the research listed, direct approach should be made to the research worker(s) engaged on a particular project. CONTENTS Alphabetical List of Subject Heads I,’.il Names and Addresses of Contributing Organisations Research in Progress Index of Researchers 69 ALPHABETICAL LIST OF SUBJECT HEADS Agriculture; Natural Resources 1 Business, Industrial & Management Studies Crime; Law; Deviance Demography i0 Economic & Social History ii Economics 15 Education 23 Human Geography; Planning 30 Language: Communications 33 Manpower; Labour; Industrial Relations 36 Politics; International Relations; Public Administration 42 Psychology; Social Psychology; Applied Psychology 47 Regional Studies 5O Social Administration; Social Medicine 55 Sociology; Social Anthropology 61 Statistics 67 (The numbers cited refer to the page(s) on which an organisation’s project(s) appears. -

Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922

Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922 CONSTITUTION OF THE IRISH FREE STATE (SAORSTÁT EIREANN) ACT, 1922. AN ACT TO ENACT A CONSTITUTION FOR THE IRISH FREE STATE (SAORSTÁT EIREANN) AND FOR IMPLEMENTING THE TREATY BETWEEN GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND SIGNED AT LONDON ON THE 6TH DAY OF DECEMBER, 1921. DÁIL EIREANN sitting as a Constituent Assembly in this Provisional Parliament, acknowledging that all lawful authority comes from God to the people and in the confidence that the National life and unity of Ireland shall thus be restored, hereby proclaims the establishment of The Irish Free State (otherwise called Saorstát Eireann) and in the exercise of undoubted right, decrees and enacts as follows:— 1. The Constitution set forth in the First Schedule hereto annexed shall be the Constitution of The Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann). 2. The said Constitution shall be construed with reference to the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland set forth in the Second Schedule hereto annexed (hereinafter referred to as “the Scheduled Treaty”) which are hereby given the force of law, and if any provision of the said Constitution or of any amendment thereof or of any law made thereunder is in any respect repugnant to any of the provisions of the Scheduled Treaty, it shall, to the extent only of such repugnancy, be absolutely void and inoperative and the Parliament and the Executive Council of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) shall respectively pass such further legislation and do all such other things as may be necessary to implement the Scheduled Treaty. -

Enhanced Belfast Campus Building User Guide Blocks BA & BB

Enhanced Belfast campus Building User Guide Blocks BA & BB Welcome to the new Ulster University Belfast campus. This practical guide will help you make the best use of the design features, services and systems of the new facilities as well as providing you with useful contacts, maps and transport information. BUILDING ORGANISATION The first thing to note is that a new naming convention is being used for the Ulster University Belfast campus. The existing building, previously known as Block 82, is now Block BA and the new extension to this building is Block BB. Blocks BA and BB are linked from the 2nd to 5th floors. To gain access to Block BB you will need to enter through the reception control point at the ground floor of Block BA marked on the diagram below as (1) before crossing to your intended floor (2). Plant Room 08 Art Studio Workspace 07 Paint Workshop Link between Blocks Studios Wood Workshop Metal Workshop 06 Foundry Link between Blocks Mould Making Fine Art 05 Faculty Presentation Link between Blocks Edit Suite Silversmithing & Jewellery Student Hub 04 Link between Blocks Ceramics Access to Library 2 Student Hub 03 Life Room Print Workshop Print Studio Library 02 24h Computing Open Access Computing Student Hub Textiles Art & Design Research Head of School, Associate Head of School, Research Institute Director Library 01 Fire Evacuation and Assembly Points Textiles GREAT PATRICK STREET Temporary Art Gallery 1 STAIR 1 Reception LIFT Building Directory STAIR 2 Entrance Library YORK STREETBLOCK BA 00 BLOCK BB 1 BUILDING UTILITY & ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION • Daylight dimming is also incorporated Ulster University has a detailed energy and into the facility. -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

General Observations About the Free State Provincial Government

A Better Life for All? Fifteen Year Review of the Free State Provincial Government Prepared for the Free State Provincial Government by the Democracy and Governance Programme (D&G) of the Human Sciences Research Council. Ivor Chipkin Joseph M Kivilu Peliwe Mnguni Geoffrey Modisha Vino Naidoo Mcebisi Ndletyana Susan Sedumedi Table of Contents General Observations about the Free State Provincial Government........................................4 Methodological Approach..........................................................................................................9 Research Limitations..........................................................................................................10 Generic Methodological Observations...............................................................................10 Understanding of the Mandate...........................................................................................10 Social attitudes survey............................................................................................................12 Sampling............................................................................................................................12 Development of Questionnaire...........................................................................................12 Data collection....................................................................................................................12 Description of the realised sample.....................................................................................12 -

The Free State, South Africa

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development THE FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA The third largest of South Africa’s nine provinces, the Free State suffers from The Free State, unemployment, poverty and low skills. Only one-third of its working age adults are employed. 150 000 unemployed youth are outside of training and education. South Africa Centrally located and landlocked, the Free State lacks obvious regional assets and features a declining economy. Jaana Puukka, Patrick Dubarle, Holly McKiernan, How can the Free State develop a more inclusive labour market and education Jairam Reddy and Philip Wade. system? How can it address the long-term challenges of poverty, inequity and poor health? How can it turn the potential of its universities and FET-colleges into an active asset for regional development? This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system T impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other he Free State, South Africa higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. CONTENTS Chapter 1. The Free State in context Chapter 2. Human capital and skills development in the Free State Chapter 3. -

Local Government Elections Election of a Councillor

Declaration by election agent as to election expenses Local government elections Election of a Councillor To be completed by the election agent to accompany the return of election expenses Please note: There is no longer any requirement for this declaration to be signed by a Justice of the Peace Election in the [county]* [county borough]* [burgh]* [district council]* [unitary authority]* [local government area]* of In the [ward]* [division]* of Date of publication of notice of the election Full name of candidate I solemnly and sincerely declare as follows: 1. I was at this election the election agent of the person named above as candidate. 2. I have examined the return of election expenses [about to be]* [delivered]* by me to the returning officer, of which a copy is now shown to me and marked _______ __, and to the best of my knowledge and belief it is a complete and accurate return as required by law. 3. To the best of my knowledge and belief, all expenses shown in the return as paid were paid by me, except as otherwise stated. * Please note delete if inapplicable Signature of declarant Date Declaration by candidate as to election expenses Local government elections Election of a Councillor To be completed by the candidate to accompany the return of election expenses Please note: There is no longer any requirement for this declaration to be signed by a Justice of the Peace Election in the [county]* [county borough]* [burgh]* [district council]* [unitary authority]* [local government area]* of In the [ward]* [division]* of Date of publication of notice of the election Full name of candidate I solemnly and sincerely declare as follows: 1.