Priyam Goswami the HISTORY of ASSAM from YANDABG to PARTITION 1826-1947

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golaghat ZP-F

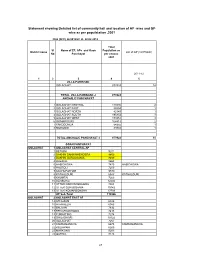

Statement showing Detailed list of community hall and location of AP -wise and GP- wise as per populatation ,2001 FEA (SFC) 26/2012/41 dt. 28.02.2012 Total Sl Name of ZP, APs and Gaon Population as District name List of GP (1st Phash) No Panchayat per census 2001 2011-12 12 3 4 5 ZILLA PARISHAD GOLAGHAT 873924 14 TOTAL ZILLA PARISHAD -I 873924 ANCHALIC PANCHAYAT 1 GOLAGHAT CENTRAL 118546 2 2 GOLAGHAT EAST 88554 1 3 GOLAGHAT NORTH 42349 1 4 GOLAGHAT SOUTH 195854 3 5 GOLAGHAT WEST 179451 3 6 GOMARIGURI 104413 2 7 KAKODONGA 54955 1 8 MORONGI 89802 1 TOTAL ANCHALIC PANCHAYAT -I 873924 14 GOAN PANCHAYAT GOLAGHAT 1 GOLAGHAT CENTRAL AP 1 BETIONI 9201 2 DAKHIN DAKHINHENGERA 9859 3 DAKHIN GURJOGANIA 8457 4 DHEKIAL 8663 5 HABICHOWA 7479 HABICHOWA 6 HAUTOLI 7200 7 KACHUPATHAR 9579 8 KATHALGURI 6543 KATHALGURI 9 KHUMTAI 7269 10 SENSOWA 12492 11 UTTER DAKHINHENGERA 7864 12 UTTER GURJOGANIA 10142 13 UTTER KOMARBONDHA 13798 AP Sub-Total 118546 GOLAGHAT 2 GOLAGHAT EAST AP 14 ATHGAON 6426 15 ATHKHELIA 6983 16 BALIJAN 7892 17 BENGENAKHOWA 7418 18 FURKATING 7274 19 GHILADHARI 10122 20 GOLAGHAT 7257 21 KAMARBANDHA 6678 KAMARBANDHA 22 KOLIAPANI 6265 23 MARKONG 5203 24 OATING 8128 23 12 3 4 5 25 PULIBOR 8908 AP Sub-Total 88554 GOLAGHAT 3 GOLAGHAT NORTH AP 26 MADHYA BRAHMAPUTRA 8091 27 MADHYA MISAMORA 7548 28 PACHIM BRAHMAPUTRA 8895 PACHIM BRAHMAPUTRA 29 PACHIM MISAMORA 8382 30 PUB MISAMORA 9433 AP Sub-Total 42349 GOLAGHAT 4 GOLAGHAT SOUTH AP 31 CHUNGAJAN 13943 32 CHUNGAJAN MAZGAON 5923 33 CHUNGAJAN MIKIR VILLAGES 7401 34 GANDHKOROI 10847 35 GELABIL 12224 36 -

Lower New Colony, Shillong-793003, Meghalaya (India) STD: 0364, Web: Neepco.Co.In

NORTH EASTERN ELECTRIC POWER CORPORATION LTD. “Brook land Compound”, Lower New Colony, Shillong-793003, Meghalaya (India) STD: 0364, Web: neepco.co.in CMD & FUNCTIONAL DIRECTORS NAME DESIGNATION TEL(OFFICE) MOBILE TEL(R) FAX E-MAIL VINOD KUMAR SINGH CMD 2224487 9650922231 2226417 [email protected] 2226453 [email protected] [email protected] ANIL KUMAR Director 2226630 9436105775 2226225 [email protected] (Personnel) ANIL KUMAR Director 2223176 9436105775 2505776 [email protected] (Finance) HEMANTA KUMAR Director 2227792 9436709095 2228520 [email protected] DEKA (Technical) [email protected] [email protected] CHIEF VIGILANCE OFFICER KHWAIRAKPAM CVO 2503652 7086099086 2229450 [email protected] PRATAP SINGH [email protected] COMPANY SECRETARIAT ABINOAM P RONG DCS 2228652 9436117663 2228652 [email protected] CMD Secretariat PARTHA PRATIM DAS GM (C) 2229778 9435559842 2226417 [email protected] [email protected] DIRECTOR (PERSONNEL) Secretariat HEMANTA BARUAH DGM(HR) 2226630 9436632420 2226225 [email protected] 7005120618 [email protected] DIRECTOR (FINANCE) Secretariat DIRECTOR (TECHNICAL) Secretariat DIGANTA GOSWAMI DGM (E/M) 9435577655 2228520 [email protected] [email protected] ANJELICA POSHNA DGM (E/M) 2226480 6009249201 2228520 [email protected] anjelicap@ neepco.co.in CORPORATE PLANNING & BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT / CORPORATE PROJECT MANAGEMENT APARAJITA CGM (Civil) 2221737 9436303944 2222126 [email protected] CHOUDHURY -

Marginalisation, Revolt and Adaptation: on Changing the Mayamara Tradition*

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 15 (1): 85–102 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2021-0006 MARGINALISATION, REVOLT AND ADAPTATION: ON CHANGING THE MAYAMARA TRADITION* BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003, Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Assam is a land of complex history and folklore situated in North East India where religious beliefs, both institutional and vernacular, are part and parcel of lived folk cultures. Amid the domination and growth of Goddess worshiping cults (sakta) in Assam, the sattra unit of religious and socio-cultural institutions came into being as a result of the neo-Vaishnava movement led by Sankaradeva (1449–1568) and his chief disciple Madhavadeva (1489–1596). Kalasamhati is one among the four basic religious sects of the sattras, spread mainly among the subdued communi- ties in Assam. Mayamara could be considered a subsect under Kalasamhati. Ani- ruddhadeva (1553–1626) preached the Mayamara doctrine among his devotees on the north bank of the Brahmaputra river. Later his inclusive religious behaviour and magical skill influenced many locals to convert to the Mayamara faith. Ritu- alistic features are a very significant part of Mayamara devotee’s lives. Among the locals there are some narrative variations and disputes about stories and terminol- ogies of the tradition. Adaptations of religious elements in their faith from Indig- enous sources have led to the question of their recognition in the mainstream neo- Vaishnava order. In the context of Mayamara tradition, the connection between folklore and history is very much intertwined. Therefore, this paper focuses on marginalisation, revolt in the community and narrative interpretation on the basis of folkloristic and historical groundings. -

The Protection of Human Rights of Rohingya in Myanmar: the Role of the International Community

Department of Political Science Master in International Relations Chair of: International Organization and Human Rights The Protection of Human Rights of Rohingya in Myanmar: The Role of The International Community CANDIDATE: SUPERVISOR: Riccardo Marzoli Professor Roberto Virzo No. 623322 CO-SUPERVISOR: Professor Francesco Cherubini Academic year: 2014/2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………...p.5 1.THE PAST: THE HISTORICAL PRESENCE OF ROHINGYA IN RAKHINE STATE. SINCE THE ORIGINS TO 1978…………………………………………………………. 9 1.1.REWRITING HISTORY: CONFLICTING VERSIONS OF BURMESE AND INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ………………………………………………………. 10 1.1.1 ETIMOLOGY OF THE TERMS…………………………………………………………………. 13 1.2. ANCIENT HISTORY OF ARAKAN AND FIRST ISLAMIC CONTACTS……… 14 1.3 CHANDRAS DINASTY AND THE ORIGINS OF THE MAGHS…………………16 1.4. MIN SAW MUN AND THE ARAKANESE KINGS WITH MUSLIM TITLES: THE SIGN OF A WIDESPREAD ISLAMIC INFLUENCE……………………………………...17 1.4.1 DIFFERENT VISIONS: WHICH ROLE FOR ROHINGYA IN MYANMAR?...................19 1.5 A NEW INFLUX: FRATRICIDAL WARS BETWEEN THE HEIRS OF THE MUGHALS’ THRONE AND THE ROLE OF THE KAMANS……………………………20 1.6 DIFFERENT WAVES OF MUSLIM ENTRANCES TO ARAKAN………………...21 1.7 1781 THE ADVENT OF THE BURMANS. THE OCCUPATION BY BODAW PAYA AND THE PREMISES OF THE BRITISH DOMINANCE ………………………………..24 1.7.1 KING SANDA WIZAYA AND THE KAMANS IN RAMREE………………………………...24 1.7.2 THE END OF THE KINGDOM OF MRAUK-U AND THE ARRIVAL OF THE AVA ARMY……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….25 1.7.3 KING BERING’S SAGA AND THE ARAKANESE -

Socio-Economic and Demographic Status of Assam: a Comparative Analysis of Assam with India Dr

International Journal of Humanities & Social Science Studies (IJHSSS) A Peer-Reviewed Bi-monthly Bi-lingual Research Journal ISSN: 2349-6959 (Online), ISSN: 2349-6711 (Print) Volume-I, Issue-III, November 2014, Page No. 108-117 Published by Scholar Publications, Karimganj, Assam, India, 788711 Website: http://www.ijhsss.com Socio-Economic and Demographic status of Assam: A comparative analysis of Assam with India Dr. Soma Dhar Research Scholar, Department of Economics, Assam University, Silchar, India Abstract The status of various indicators like, Socio-economic height, representation of demographic, human development ranking etc. can give us a rough picture about our economy. Assam is one of among the eight Sister States of North East India. It is the land of hills, valleys, mighty river Brahmaputra. The paper is based on the secondary data. The broad objective of the paper is to highlight the various facts & figures of Assam and compare these with facts & figures of all India averages. The analysis of the data shows that, though in some cases the performance of state Assam is satisfactorily than the all India average. But in major other areas, the position and performance of Assam is not satisfactorily compared to the all India average. In case of various socio-economic, demographic, human development indicators Assam is far behind from India. Key Wards: Socio-economic condition, Demographic status, Human development rank, Gender development, Nutrition status etc. Socio-economic condition and representation of demographic, human development status etc. are some important indicators which help to measure the development level of any community or state. According to Afzal (1995) and Bose (2006) development of medical science has improved the longevity of human population at the same time there are strong and well documented associations between health and socio-economic and other factors. -

Gazetteer of India Tirap District

Gazetteer of India ARUNACHAL PRADESH Tirap District GAZETTEER OF INDIA ARUNACHAL PRADESH TIRAP DISTRICT ARUNACHAL PRADESH DISTRICT GAZETTEERS TIRAP DISTRICT Edited by S. DUTTA CHOUDHURY GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1980 Published by Shri R.N. Bagchi Director of Information and Public Relations Government of Arunachal Pradesh, Shillong Printed by N.K, Gossain & Co. Private Ltd. 13/7ArifFRoad Calcutta 700 067 © Government of Arunachal Pradesh First Edition: 1980 First Reprint Edition: 2008 ISBN--978-81-906587-1-3 Price: Rs. 225/- Reprinted by M/s Himalayan Publishers Legi Shopping Con^jlex, BankTinali,ltanagar-791 111. FOREWORD I am happy to know that the Tirap District Gazetteer is soon coming out. This will be the second volume of District Gazetteers of Arunachal Pradesh — the first one on Lohit District was published during last year. The Gazetteer presents a comprehensive view of the life in Tirap District. The narrative covers a wide range of subjects and contains a wealth of information relating to the life style of the people, the geography of the area and also developments made so far in various sectors. The Tirap District Gazetteer, 1 hope, would serve a very useful purpose as a reference book. Raj Niwas R. N. Haldipur ltanagar-791111 Lieutenant Governor, Arunachal Pradesh May 6. 1980 PREFACE The present volume is the second in the series of Arunachal Pradesh District Gazetteers. The publication of this volume is the work of the Gazetteers Department of the Government of Arunachal Pradesh, carried out persistently over a number of years. In fact, the draft of Tirap District Gazetteer passed through a long course of examinations, changes and rewriting until the revised draft recommended by the Advisory Board in 1977 was approved by the Government of Arunachal Pradesh in 1978 and finally by the Government of India in 1979. -

Department of Statistics Assam University, Silchar

DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS ASSAM UNIVERSITY, SILCHAR List of Registered Alumni of the Department of Statistics, Assam University, Silchar All of them have pursued M. Sc (Statistics) program from the department Year of Your Current Your Current Mobile completion Affiliation Designation Sl. No. Name E-mail Number Debopama 2016 None None 1 Bhattacharya [email protected] 8133078014 Business, place 2016 Bongaigaon Entrepreneur 2 Dipshikha Baruah [email protected] 8638415125 RKP ASSOCIATES, Janiganj Bazar, 2016 Silchar, Pin-788001 Senior Assistant 3 Piyali Ghosh [email protected] 9435586758 Bakhal Dhar LPS, Anupama Paul [email protected] 7578971845 2016 Cachar Assistant Teacher 4 Srikishan Sarda Smita Dev [email protected] 9954167249 2016 College, Hailakandi Guest faculty 5 1 Year of Your Current Your Current Mobile completion Affiliation Designation Sl. No. Name E-mail Number Alankit House, Guwahati Anupoma Singha [email protected] 6002629655 2016 Ullubari,781007 Data Entry Operator 6 Evelyn learning Pvt. Limited, Ghitorni, New Subject matter expert 2017 Delhi (Statistics) 7 Aditi Chakraborty [email protected] 8486151814 Department of Statistics, Institute of Science, Banaras Senior Research 2017 Hindu University Fellow 8 Utpal Dhar Das [email protected] 9932312411 Bireshwar 2018 None None 9 Bhattacharjee [email protected] 9531045037 2018 None Private Tutor 10 Bornali Das [email protected] 8811932588 Studying PG diploma in Statistical Methods and Analytics at ISI, 2018 Tezpur Student 11 Indrajit Mazumder [email protected] 7002082656 Rangirkhari, Lane 2018 no.1, House no. 16 Student 12 Satabdi Roy [email protected] 9101489340 Studying at teachers' training college , 2018 silchar , assam Students 13 Suraj Goswami [email protected] 8638527300 2019 None None 14 Bikram Jyoti Sinha [email protected] 7086434306 2 Year of Your Current Your Current Mobile completion Affiliation Designation Sl. -

Tourism Sector in Assam: Its Economic Contribution and Challenges Purabi Gogoi Research Scholar, Dept

Pratidhwani the Echo A Peer-Reviewed International Journal of Humanities & Social Science ISSN: 2278-5264 (Online) 2321-9319 (Print) Impact Factor: 6.28 (Index Copernicus International) Volume-VI, Issue-II, October 2017, Page No. 214-219 Published by Dept. of Bengali, Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam, India Website: http://www.thecho.in Tourism Sector in Assam: Its Economic Contribution and Challenges Purabi Gogoi Research Scholar, Dept. of Economics, Dibrugarh University, Assam, India Abstract Assam is endowed with natural and cultural resources which can form the basis for a very lucrative tourism industry creating employment and generating revenues. Though, it has the great potentialities for the development of tourism, but due to very limited government funds made available to the tourism sector and other various types of challenges, its contribution is not so much encouraging. To encourage tourism sector in Assam, proper infrastructure facilities, trained tourist guide and also proper cooperation and help of public, private and NGOs sector is needed. Keywords: Assam, Tourism, Economic contribution Introduction: Tourism primarily relates to movement of people to places outside their usual place of residence, pleasure being the usual motivation. It induces economic activity either directly or indirectly. This could be in terms of economic output or in terms of employment generation, besides other social and infrastructural dimensions. Assam is endowed with natural and cultural resources which can form the basis for a very lucrative tourism industry creating employment and generating income not only in the urban centers but also in the rural areas. Assam can become one of the most destinations of tourism in India because of its magnificent tourism products like exotic wildlife, awesome scenic beauty, colorful fairs and festivals, age old historical monuments, lush green tea gardens and golf courses, massive river Brahmaputra and its tributaries. -

Assam and the Brahmaputra: Recurrent Flooding and Internal Displacement Sabira Coelho

The State of Environmental Migration 2011 ASSAM AND THE BRAHMAPUTRA: RECURRENT FLOODING AND INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT SABIRA COELHO Assam epitomizes images of natural beauty: wild- flood-prone regions of the country and even for life sanctuaries, tea estates and lush rainforests. It other countries in South Asia, like Bangladesh, who is the largest of the “seven sisters”, the states that confront the same issue. Also, solving the conun- make up the north-eastern wing of India. Right drum faced by Majuli, a sinking river island, would through the heart of this state runs the Brahma- contribute to possible solutions for island nations putra, the second largest braided river in the world, that could face the same predicament in the future. known for its meandering and frequent changes The first section of the paper will give an outline of course (Brahmaputra Board, ). The name of the demographics of the region, including the Brahmaputra means “the son of Brahma”, who existing migration patterns. The second section in Hindu mythology is the creator of all humans will discuss the floods (focusing on ) and con- and along with Vishnu, the preserver, and Shiva, sequent environmental degradation, its influence the destroyer, forms the “Great Trinity”. The Brah- on demographic trends and the prospects in light maputra created Majuli, a river island situated of climate change. The final section will assess the mid-stream, by gradually depositing sediment to policies relating to flood control and dealing with form an alluvial plain (ASI, ). However, the internal migration. Brahmaputra over time is transforming into Shiva, evidenced by the destruction it has caused in the Assamese part of the Brahmaputra river valley. -

Empire's Garden: Assam and the Making of India

A book in the series Radical Perspectives a radical history review book series Series editors: Daniel J. Walkowitz, New York University Barbara Weinstein, New York University History, as radical historians have long observed, cannot be severed from authorial subjectivity, indeed from politics. Political concerns animate the questions we ask, the subjects on which we write. For over thirty years the Radical History Review has led in nurturing and advancing politically engaged historical research. Radical Perspec- tives seeks to further the journal’s mission: any author wishing to be in the series makes a self-conscious decision to associate her or his work with a radical perspective. To be sure, many of us are currently struggling with the issue of what it means to be a radical historian in the early twenty-first century, and this series is intended to provide some signposts for what we would judge to be radical history. It will o√er innovative ways of telling stories from multiple perspectives; comparative, transnational, and global histories that transcend con- ventional boundaries of region and nation; works that elaborate on the implications of the postcolonial move to ‘‘provincialize Eu- rope’’; studies of the public in and of the past, including those that consider the commodification of the past; histories that explore the intersection of identities such as gender, race, class and sexuality with an eye to their political implications and complications. Above all, this book series seeks to create an important intellectual space and discursive community to explore the very issue of what con- stitutes radical history. Within this context, some of the books pub- lished in the series may privilege alternative and oppositional politi- cal cultures, but all will be concerned with the way power is con- stituted, contested, used, and abused. -

History of North East India (1228 to 1947)

HISTORY OF NORTH EAST INDIA (1228 TO 1947) BA [History] First Year RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY Arunachal Pradesh, INDIA - 791 112 BOARD OF STUDIES 1. Dr. A R Parhi, Head Chairman Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University 2. ************* Member 3. **************** Member 4. Dr. Ashan Riddi, Director, IDE Member Secretary Copyright © Reserved, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. “Information contained in this book has been published by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, IDE—Rajiv Gandhi University, the publishers and its Authors shall be in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use” Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi – 110 055 Website: www.vikaspublishing.com Email: [email protected] About the University Rajiv Gandhi University (formerly Arunachal University) is a premier institution for higher education in the state of Arunachal Pradesh and has completed twenty-five years of its existence. -

Golaghat District, Assam

Ground Water Information Booklet Golaghat District, Assam Central Ground Water Board North Eastern Region Ministry of Water Resources Guwahati August 2013 .GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET GOLAGHAT DISTRICT, ASSAM DISTRICT AT AGLANCE Sl Items Statistics No 1 GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical Area (in sq.km) 3,502 ii) Population 10,58,674 iii) Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 2,118.6 2 GEOMORPHOLOGY i) Major physiographic units Brahmaputra plane, marshy land and low altitude structural hills in the extreme south. ii) Major drainages Brahmaputra River and Dhansiri, Galabil, Desoi, Kakodanga Rivers 3 LAND USE (sq.km) i) Forest area 1,56,905 ii) Net area sown 1,19,046 iii) Total cropped area 1,84,497 iv) Area sown more than once 65,451 4 MAJOR SOIL TYPES Alluvial and flood plain soils 5 AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS as 558.76 on 2006(sq. km) 6 IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT 41.49 SOURCES (sq.km.) 7 NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER 11 MONITORING STATIONS OF CGWB (as on March 2013). 8 PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Quaternary formation followed by FORMATIONS Tertiary/Pre-Cambrian deposit 9 HYDROGEOLOGY i) Major water bearing Vast alluvial formation of river borne formations deposit ii) Pre-monsoon water level 3.8 -7.96 m bgl during 2007 iii) Post monsoon water level 3.31 -6.89 m bgl during 2007 iv) Long term water level trend in Rising 10 years(1998-2007) in m/year 10 GROUND WATER EXPLORATION BY CGWB (as on 28.02.2013). i) No of wells drilled 12 (8 EW, 3 OW, 1 PZ) ii) Depth range in meters 100 -305 iii) Discharge in lps 1.33 – 60.00 iv) Transmissivity(m2/day) 415-5,041 11 GROUND WATER QUALITY Fe : 0.10 – 4.60 i) Presence of chemical constituents EC : 56.00 – 820.00 more than permissible limit (mg/l)(i.e.,EC,F,Fe,As) 12 DYANMIC GROUND WATER RESOURCES (2009) in mcm.