“Perhaps I'd Better Go Back to Mr. Jadassohn”: Charles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Karg-Elert 1869 Text

Zu den wenigen gelungenen Werken, die eine „einstimmige“ poly- Karg-Elert’s Sonata for clarinet solo op. 110 is one phone Architektur aufweisen, darf Karg-Elerts Sonate für Klari- of the few successful works with a “one-voiced” poly- nette solo op. 110 gezählt werden. Ein impressionistischer Duktus phonic architecture. An impressionistic approach with mit ihren vom Komponisten akribisch gesetzten Vortragsbeschrei- meticulously placed signs of expression underlines and bungen betont und verdeutlicht diesen außergewöhnlichen Ver- clarifies this unusual attempt at an extremely mini- such, die extrem miniaturisierte „lineare“ Anlage der Sonate noch aturized “linear” sonata form. Despite references to erfahrbar zu machen. Auch wenn Anklänge aus der Zeit mit- the time when the highly gifted Karg-Elert was still schwingen, als der hochbegabte Karg-Elert noch zu den beken- a “comrade of contemporary music” with its aleatoric nenden „Mitstreitern der Musik seiner Gegenwart“ mit ihren “noises” and search for new soundscapes, one can but aleatorischen „Geräuschsachen“ auf der Suche nach neuen Klang- wonder why he later left this experimental phase to schemen gehörte, bleibt zu fragen, warum er später diese expe- immerse himself in virtuosic and impressionist forms, rimentelle Phase seines Schaffens verließ, um in die Sprache paying tribute to the melodic-tonal heritage. His bril- virtuos-impressionistischer Gestaltungsformen einzutauchen und liant music-theoretical skills no doubt helped him dem melodisch-tonalen Erbe Tribut zu zollen? Seine glänzenden spice up his harmonies without any loss of tonal disci- musiktheoretischen Kenntnisse dürften ihm dazu verholfen pline. This also applies to his handling of the instru- haben, die Harmonik auszureizen, ohne daß die tonalen Dis- ments: their specific timbre and range, as in theTrio for ziplinen verlorengingen. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright ALFRED HILL’S VIOLA CONCERTO: ANALYSIS, COMPOSITIONAL STYLE AND PERFORMANCE AESTHETIC Charlotte Fetherston A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, NSW 2014 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. -

On the Trail of Jewish Music Culture in Leipzig

Stations Mendelssohn-Haus (Notenspur-Station 2) On the trail of Jewish Mendelssohn House (Music Trail Station 2) / Goldschmidtstraße 12 The only preserved house and at the same time the deathbed of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847), conductor of Leipzig’s Gewandhaus and founder of the rst German conservatory. music culture in Leipzig Musikverlag C.F.Peters / Grieg-Begegnungsstätte (Notenspur-Station 3) C.F.Peters Publishers/Grieg Memorial Centre (Music Trail Station 3) / Talstraße 10 Headquarters of the Peters’ Publishing Company since 1874, expropriated by the National Socialists in 1939; Henri Hinrichsen, the publishing manager and benefactor, was murdered in Auschwitz Concentration Camp in 1942. Wohnhaus von Gustav Mahler (Notenbogen-Station 4, Notenrad-Station 13) Gustav Mahler’s Residence (Music Walk Station 4, Music Ride Station 13) / Gustav-Adolf-Str.aße12 The opera conductor Gustav Mahler (1869-1911) lived in this house from 1887 till 1888 and composed his Symphony No.1 here. Wohnhaus von Erwin Schulho (Notenbogen-Station 6) Erwin Schulho ‘s Residence (Music Walk Station 6) / Elsterstraße 35 Composer and pianist Erwin Schulho (1894-1942) lived here during his studies under the instruction of Max Reger between 1908 and 1910. Schulho died in Wülzburg Concentration Camp in 1942. Hochschule für Musik und Theater „Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy“ - Max Reger (Notenbogen-Station 9, Notenrad-Station 3) Leipzig Conservatory named after its founder Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (Music Walk Station 9, Music Ride Station 3) / Grassistraße 8 The main building of the Royal Conservatory founded by Mendelssohn, inaugurated in 1887; place of study and instruction of prominent Jewish musicians such as Salomon Jadassohn, Barnet Licht, Wilhelm Rettich, Erwin Schulho , Günter Raphael and Herman Berlinski. -

Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia Or Online at Wrti.Org

Next on Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia or online at wrti.org. Encore presentations of the entire Discoveries series every Wednesday at 7:00 p.m. on WRTI-HD2 Saturday, November 7, 2009, 5:00-6:00 p.m. Salomon Jadassohn (1831-1902). Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor (1887). Markus Becker, piano, Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Michael Sanderling. Hyperion 67636. Tr 4-6. 23:51 Gloria Coates (b.1938). Symphony No. 7 (1991). Stuttgart Philharmonic, Georg Schmöhe. CPO 999392-2. Tr 4- 6. 25:16 The 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall is on November 9th, 2009. Inspired by this historic event, the American composer Gloria Coates (who has lived in Germany for years) dedicated her seventh symphony “to those who brought down the Wall in PEACE.” Salomon Jadassohn was an eminent composer, pianist, conductor, and teacher in Germany. Although he died in 1902, his works were banned by anti-Semitic followers of Wagner in the 1930s. Fortunately, his music (ironically influenced by Richard Wagner) is beginning to be heard once again. Jadassohn attended the Leipzig Conservatory shortly after its founding by Felix Mendelssohn and eventually taught piano and composition there. He had studied piano with Ignaz Moscheles and Franz Liszt, and among his influences in composition were Liszt and Wagner. He was a well-respected teacher who produced manuals on harmony, counterpoint, and orchestration that were used for years. Grieg, Delius, and one of last month’s composers on Discoveries, George Chadwick, all studied with him. His many works, including this inventive second concerto, are wonderful examples of the Romantic idiom. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0107 Notes

TOCCATA CLASSICS Salomon JADASSOHN Piano Trios No. 1 in F major, Op. 16 No. 2 in E major, Op. 20 No. 3 in C minor, Op. 59 Syrius Trio FIRST RECORDINGS SALOMON JADASSOHN: Piano Trios Nos. 1–3 by Malcolm MacDonald Salomon Jadassohn’s name is moderately familiar to musicologists, but only because he was an important teacher, many of whose students went on to make a considerable reputation for themselves: the roll-call includes Albéniz, Alfano, Bortkiewicz, Busoni, Chadwick, Čiurlionis, Delius, Fibich, Grieg, Kajanus, Karg-Elert, Reznicek, Georg Schumann, Sinding and Weingartner. Until recently Jadassohn’s own music has been virtually ignored, but it is beginning to emerge from the shadows. "e three piano trios on this disc are not among the most important essays in the genre to emerge from nineteenth-century Germany, but they are full of highly enjoyable music, written to give pleasure, while being economically constructed with considerable skill and ingenuity. Jadassohn was born into a Jewish family in Breslau, the capital of the Prussian province of Silesia (now Wrocław in Poland), on 13 August 1831 and enrolled in the Leipzig Conservatorium in 1848, where his composition teachers were Moritz Hauptmann, Ernst Richter and Julius Rietz. He studied piano, moreover, with Beethoven’s friend and protégé Ignaz Moscheles. From 1849 to 1851, by contrast, and to the disquiet of some of his teachers, Jadassohn also became a private pupil of Franz Liszt in Weimar. He spent most of his subsequent career teaching in Leipzig. As a Jew, he was unable to apply for any of the Leipzig church-music posts that were open to other graduates from the Conservatory; instead, he worked for a synagogue and supported himself otherwise mainly as a teacher of piano. -

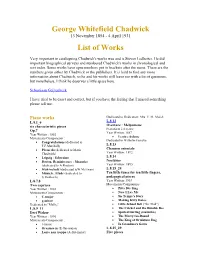

George Whitefield Chadwick List of Works

George Whitefield Chadwick 13 November 1854 - 4 April 1931 List of Works Very important in cataloguing Chadwick's works was and is Steven Ledbetter. He did important biographical surveys and numbered Chadwick's works in chronological and sort order. Some works have opus numbers put in brackets after the name. These are the numbers given either by Chadwick or the publishers. It is hard to find any more information about Chadwick, so he and his works still leave me with a lot of questions, but nonetheless, I think he deserves a little space here. Sebastiaan Geijtenbeek I have tried to be exact and correct, but if you have the feeling that I missed something please tell me. Piano works Dedicated to Dedication: Mrs. E. M. Marsh L.8.1_6 L.8.12 six characteristic pieces Overture : Melpomene Op.7 Pianoforte à 4 mains Year Written: 1887 Year Written : 1882 Movements/Components : Lento e dolente Dedicated to Wilhelm Gericke Congratulations (dedicated to F.F.Marshall) L.8.13 Please do (dedicated to Marie Chanson orientale Chadwick) Year Written : 1892 Leipzig : Scherzino L.8.14 Boston, Reminiscence : Mazurka Nocturne (dedicated to A.Preston) Year Written : 1895 Irish melody (dedicated toW.McEwen) L.8.15_24 Munich : Etude (dedicated to Ten little tunes for ten little fingers, G.Heubach) pedagogical pieces L.8.7,8 Year Written: 1903 Two caprices Movements/Components : Year Written : 1888 Pitty Itty Sing Movements/Components : Now I Lay Me C-major Sis Tempy's Story g-minor Making Kitty Dance Dedicated to "Mollie" Little School Bell ("for -

ITALIAN, PORTUGUESE, SPANISH and LATIN AMERICAN SYMPHONIES from the 19Th Century to the Present

ITALIAN, PORTUGUESE, SPANISH AND LATIN AMERICAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman FRANCO ALFANO (1876-1960, ITALY) Born in Posillipo, Naples. After studying the piano privately with Alessandro Longo, and harmony and composition with Camillo de Nardis and Paolo Serrao at the Conservatorio di San Pietro a Majella, Naples, he attended the Leipzig Conservatory where he completed his composition studies with Salomon Jadassohn. He worked all over Europe as a touring pianist before returning to Italy where he eventually settled in San Remo. He held several academic positions: first as a teacher of composition and then director at the Liceo Musicale, Bologna, then as director of the Liceo Musicale (later Conservatory) of Turin and professor of operatic studies at the Conservatorio di San Cecilia, Rome. As a composer, he speacialized in opera but also produced ballets, orchestral, chamber, instrumental and vocal works. He is best known for having completed Puccini’s "Turandot." Symphony No. 1 in E major "Classica" (1908-10) Israel Yinon/Brandenburg State Orchestra, Frankfurt ( + Symphony No. 2) CPO 777080 (2005) Symphony No. 2 in C major (1931-2) Israel Yinon/Brandenburg State Orchestra, Frankfurt ( + Symphony No. 1) CPO 777080 (2005) ANTONIÓ VICTORINO D'ALMEIDA (b.1940, PORTUGAL) Born in Lisbon.. He was a student of Campos Coelho and graduated from the Superior Piano Course of the National Conservatory of Lisbon. He then studied composition with Karl Schiske at the Vienna Academy of Music. He had a successful international career as a concert pianist and has composed prolifically in various genres including: instrumental piano solos, chamber music, symphonic pieces and choral-symphonic music, songs, opera, cinematic and theater scores. -

Fifty-Eighth National Conference November 5–7, 2015 JW Marriott Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana

Fifty-Eighth National Conference November 5–7, 2015 JW Marriott Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana ABSTRACTS & PROGRAM NOTES updated October 30, 2015 Abeles, Harold see Ondracek-Peterson, Emily (The End of the Conservatory) Abeles, Harold see Jones, Robert (Sustainability and Academic Citizenship: Collegiality, Collaboration, and Community Engagement) Adams, Greg see Graf, Sharon (Curriculum Reform for Undergraduate Music Major: On the Implementation of CMS Task Force Recommendations) Arnone, Francesca M. see Hudson, Terry Lynn (A Persistent Calling: The Musical Contributions of Mélanie Bonis and Amy Beach) Bailey, John R. see Demsey, Karen (The Search for Musical Identity: Actively Developing Individuality in Undergraduate Performance Students) Baldoria, Charisse The Fusion of Gong and Piano in the Music of Ramon Pagayon Santos Recipient of the National Artist Award, Ramón Pagayon Santos is an icon in Southeast Asian ethnomusicological scholarship and composition. His compositions are conceived within the frameworks of Philippine and Southeast Asian artistic traditions and feature western and non- western elements, including Philippine indigenous instruments, Javanese gamelan, and the occasional use of western instruments such as the piano. Receiving part of his education in the United States and Germany (M.M from Indiana University, Ph. D. from SUNY Buffalo, studies in atonality and serialism in Darmstadt), his compositional style developed towards the avant-garde and the use of extended techniques. Upon his return to the Philippines, however, he experienced a profound personal and artistic conflict as he recognized the disparity between his contemporary western artistic values and those of postcolonial Southeast Asia. Seeking a spiritual reorientation, he immersed himself in the musics and cultures of Asia, doing fieldwork all over the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia, resulting in an enormous body of work. -

Revising Perspectives on Nineteenth-Century Jewish Composers: a Case Study Comparison of Ignaz Brüll and Salomon Jadassohn

Revising Perspectives on Nineteenth-Century Jewish Composers: A Case Study Comparison of Ignaz Brüll and Salomon Jadassohn by Adana Whitter B.A., Universit y of British Columbia, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) March 2013 © Adana Whitter, 2013 i Abstract The influence of anti-Semitism on the lives and careers of Jewish musicians within the social climate of nineteenth-century Europe is well known. Pamela Potter, Sander Gilman, Philip Bohlman, and K. M. Knittel have thoroughly explored the anti-Semitic treatment of Jewish composers during this period. Definitions of the experience of Jewish composers have been crystallized on the basis of prominent cases, such as Gustav Mahler or Alexander Zemlinsky, who were actively discussed in the press or other publications. The goal of this study is to examine whether the general view of anti-Semitism, as shown in those studies, applies to other Jewish composers. To this aim, this thesis will introduce two lesser known Jewish composers, Ignaz Brüll (1846-1907) and Salomon Jadassohn (1831-1902) as case studies, consider closely their particular situations at the end of the nineteenth century, and assess their positions vis-à-vis the general views of how musician Jews were treated in these societies. Chapter One outlines the historical and political context in Germany and Austria, where these two composers resided, in order to understand where they fit into that context. Chapter Two focuses on Jewishness in music, the difficulties involved in defining Jewish music, along with the contributions of other Jewish composers to the wider European culture, and makes clear the important part anti- Semitism played in the process of identification during this period. -

Sullivan-Journal Nr. 10 (Dezember 2013)

Sullivan-Journal Nr. 10 (Dezember 2013) Diese Ausgabe des Sullivan-Journals greift Themen auf, die im Mai nächsten Jahres mit dem Folgeband von SullivanPerspektiven weiter vertieft werden. Sullivans Erfahrungen in Leipzig spielen auch in dem erneut von Albert Gier, Meinhard Saremba und Benedict Taylor herausge- gebenen Buch SullivanPerspektiven II – Arthur Sullivans Bühnenwerke, Oratorien, Schau- spielmusik und Lieder eine Rolle, und zwar in einem Beitrag über die Einflüsse der deutschen Oper auf Sullivans Wirken in Großbritannien. Die Hintergrundinformationen zu der Kantate The Martyr of Antioch in diesem Journal bieten eine wesentliche Grundlage für die musikali- schen und literarischen Analysen dieses Werks in dem geplanten Buch. Und mit dem Beitrag von Klaus Aringer und Martin Haselböck ergänzen wir Roger Norringtons Essay aus dem ers- ten Band von SullivanPerspektiven über Sullivans Klangwelt. Die Hinweise zum Orchester in Weimar – das nicht allzu weit von Sullivans Studienort Leipzig entfernt liegt – und zur Instru- mentalentwicklung im 19. Jahrhundert tragen zu einem weiter reichenden Verständnis von Sul- livans musikalischen Erfahrungen bei. Darüber hinaus berichten wir über einen sensationellen Fund von Sullivan-Texten, die Jahr- zehnte lang der Aufmerksamkeit entgangen waren. Unser besonderer Dank für die Unterstützung bei der Recherche geht vor allem an die Kurato- rin Frances Barulich der Morgan Library in New York (Mary Flagler Cary Curator of Music Manuscripts and Printed Music, The Morgan Library & Museum), sowie an die -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Americans at the Leipzig Conservatory (1843–1918) and Their Impact on AJoamnnae Perpipclean Musical Culture Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AMERICANS AT THE LEIPZIG CONSERVATORY (1843–1918) AND THEIR IMPACT ON AMERICAN MUSICAL CULTURE By JOANNA PEPPLE A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 Copyright © 2019 Joanna Pepple Joanna Pepple defended this dissertation on December 14, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: S. Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation George Williamson University Representative Sarah Eyerly Committee Member Iain Quinn Committee Member Denise Von Glahn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii Soli Deo gloria iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so grateful for many professors, mentors, family, and friends who contributed to the success of this dissertation project. Their support had a direct role in motiving me to strive for my best and to finish well. I owe great thanks to the following teachers, scholars, librarians and archivists, family and friends. To my dissertation committee, who helped in shaping my thoughts and challenging me with thoughtful questions: Dr. Eyerly for her encouragement and attention to detail, Dr. Quinn for his insight and parallel research of English students at the Leipzig Conservatory, Dr.