A Study and Performance Guide of George Chadwick’S a Flower Cycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Symphony Hall, Boston Huntington and Massachusetts Avenues

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Branch Exchange Telephones, Ticket and Administration Offices, Back Bay 149 1 lostoai Symphony QreSnesfe©J INC SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor FORTY-FOURTH SEASON, 1924-1925 PiroErainriime WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1925, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TPJ 5TEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. » FREDERICK P. CABOT . Pres.dent GALEN L. STONE ... Vice-President B. ERNEST DANE .... Treasurei FREDERICK P. CABOT ERNEST B. DANE HENRY B. SAWYER M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE GALEN L. STONE JOHN ELLERTON LODGE BENTLEY W, WARREN ARTHUR LYMAN E. SOHlER WELCH W. H. BRENNAN. Manager C E. JUDD Assistant Manager 1429 — THE INST%U<SMENT OF THE IMMORTALS IT IS true that Rachmaninov, Pader- Each embodies all the Steinway ewski, Hofmann—to name but a few principles and ideals. And each waits of a long list of eminent pianists only your touch upon the ivory keys have chosen the Steinway as the one to loose its matchless singing tone, perfect instrument. It is true that in to answer in glorious voice your the homes of literally thousands of quickening commands,, to echo in singers, directors and musicai celebri- lingering beauty or rushing splendor ties, the Steinway is an integral part the genius of the great composers. of the household. And it is equally true that the Steinway, superlatively fine as it is, comet well within the There is a Steinway dealer in your range of the inoderate income and community or near you through "whom meets all the lequirements of the you may purchase a new Steinway modest home. -

Karg-Elert 1869 Text

Zu den wenigen gelungenen Werken, die eine „einstimmige“ poly- Karg-Elert’s Sonata for clarinet solo op. 110 is one phone Architektur aufweisen, darf Karg-Elerts Sonate für Klari- of the few successful works with a “one-voiced” poly- nette solo op. 110 gezählt werden. Ein impressionistischer Duktus phonic architecture. An impressionistic approach with mit ihren vom Komponisten akribisch gesetzten Vortragsbeschrei- meticulously placed signs of expression underlines and bungen betont und verdeutlicht diesen außergewöhnlichen Ver- clarifies this unusual attempt at an extremely mini- such, die extrem miniaturisierte „lineare“ Anlage der Sonate noch aturized “linear” sonata form. Despite references to erfahrbar zu machen. Auch wenn Anklänge aus der Zeit mit- the time when the highly gifted Karg-Elert was still schwingen, als der hochbegabte Karg-Elert noch zu den beken- a “comrade of contemporary music” with its aleatoric nenden „Mitstreitern der Musik seiner Gegenwart“ mit ihren “noises” and search for new soundscapes, one can but aleatorischen „Geräuschsachen“ auf der Suche nach neuen Klang- wonder why he later left this experimental phase to schemen gehörte, bleibt zu fragen, warum er später diese expe- immerse himself in virtuosic and impressionist forms, rimentelle Phase seines Schaffens verließ, um in die Sprache paying tribute to the melodic-tonal heritage. His bril- virtuos-impressionistischer Gestaltungsformen einzutauchen und liant music-theoretical skills no doubt helped him dem melodisch-tonalen Erbe Tribut zu zollen? Seine glänzenden spice up his harmonies without any loss of tonal disci- musiktheoretischen Kenntnisse dürften ihm dazu verholfen pline. This also applies to his handling of the instru- haben, die Harmonik auszureizen, ohne daß die tonalen Dis- ments: their specific timbre and range, as in theTrio for ziplinen verlorengingen. -

Sunday,July 20,2014 3:00Pm

SUNDAY, JULY 20, 2014 3:00PM MADONNA DELLA STRADA CHAPEL MARILYN KEISER, ORGAN Sonata in A Major, Op. 65, No. 3 Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) 1) Con moto maestoso Sinfonia from Cantata 29 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) trans. Marcel Dupré (1886-1971) Ich hatte viel Bekummerniss, from Cantata 21 Johann Sebastian Bach arr. Harvey Grace (1874-1944) Ein feste Burg, from Cantata 80 Johann Sebastian Bach arr. Gerald Near (b. 1942) Sonata Number 8, Op. 132 Josef Rheinberger (1839-1901) 1) Introduction 4) Passacaglia Salem Sonata (2003) Dan Locklair (b.1949) 2) “Hallowed be thy name…” 3) “…We owe thee thankfulness and praise…” Phoenix Processional Dan Locklair Concert Variations on the Austrian Hymn, Op. 3 John Knowles Paine (1839-1906) Symphony 1, Op. 14 Louis Vierne (1870-1937) 4) Allegro Vivace Carillon de Westminster, Op. 54, no. 6 Louis Vierne Marilyn Keiser is Chancellor’s Professor of Music Emeritus at Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, Bloomington, where she taught courses in sacred music and applied organ for 25 years. Prior to her appointment at Indiana University, Dr. Keiser was Organist and Director of Music at All Souls Parish in Asheville, North Carolina and Music Consultant for the Episcopal Diocese of Western North Carolina, holding both positions from 1970 to 1983. A native of Springfield, Illinois, Marilyn Keiser began her organ study with Franklin Perkins, then attended Illinois Wesleyan University where she studied organ with Lillian McCord, graduating with a Bachelor of Sacred Music degree. Dr. Keiser entered the School of Sacred Music at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, where she studied organ with Alec Wyton and graduated summa cum laude in 1965 with a Master of Sacred Music degree. -

On the Trail of Jewish Music Culture in Leipzig

Stations Mendelssohn-Haus (Notenspur-Station 2) On the trail of Jewish Mendelssohn House (Music Trail Station 2) / Goldschmidtstraße 12 The only preserved house and at the same time the deathbed of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847), conductor of Leipzig’s Gewandhaus and founder of the rst German conservatory. music culture in Leipzig Musikverlag C.F.Peters / Grieg-Begegnungsstätte (Notenspur-Station 3) C.F.Peters Publishers/Grieg Memorial Centre (Music Trail Station 3) / Talstraße 10 Headquarters of the Peters’ Publishing Company since 1874, expropriated by the National Socialists in 1939; Henri Hinrichsen, the publishing manager and benefactor, was murdered in Auschwitz Concentration Camp in 1942. Wohnhaus von Gustav Mahler (Notenbogen-Station 4, Notenrad-Station 13) Gustav Mahler’s Residence (Music Walk Station 4, Music Ride Station 13) / Gustav-Adolf-Str.aße12 The opera conductor Gustav Mahler (1869-1911) lived in this house from 1887 till 1888 and composed his Symphony No.1 here. Wohnhaus von Erwin Schulho (Notenbogen-Station 6) Erwin Schulho ‘s Residence (Music Walk Station 6) / Elsterstraße 35 Composer and pianist Erwin Schulho (1894-1942) lived here during his studies under the instruction of Max Reger between 1908 and 1910. Schulho died in Wülzburg Concentration Camp in 1942. Hochschule für Musik und Theater „Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy“ - Max Reger (Notenbogen-Station 9, Notenrad-Station 3) Leipzig Conservatory named after its founder Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (Music Walk Station 9, Music Ride Station 3) / Grassistraße 8 The main building of the Royal Conservatory founded by Mendelssohn, inaugurated in 1887; place of study and instruction of prominent Jewish musicians such as Salomon Jadassohn, Barnet Licht, Wilhelm Rettich, Erwin Schulho , Günter Raphael and Herman Berlinski. -

November 20, 2016 an Afternoon of Chamber Music

UPCOMING CONCERTS AT THE OREGON CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT SOUTHERN OREGON UNIVERSITY Thursday, December 1 at 7:30 p.m. SOU Wind Ensemble Friday, December 2 at 7:30 p.m. SOU Percussion Ensemble Saturday, December 3 at 7:30 p.m. Rogue Valley Symphony – Messiah Sunday, December 4 at 3:00 p.m. SOU Chamber and Concert Choirs Sunday, December 4 at 7:30 p.m. (in band room, #220) Maraval Steel Pan Band Friday, December 9 at 7:30 p.m. Saturday, December 10 at 3:00 p.m. Thomas Stauffer, cello Sunday, December 11 at 3:00 p.m. Siskiyou Singers, Haydn, Maria Theresa Mass with Orchestra Larry Stubson, violin Saturday, December 17 at 7:30 p.m. Sunday, December 18 at 3:00 p.m. Margaret R. Evans, organ Southern Oregon Repertory Singers Friday, December 30 at 7:30 p.m. Chamber Music Concerts – Gabe Young, Oboe, and Jodi French, piano An Afternoon of Chamber Music Music at SOU November 20, 2016 ▪ 3:00 p.m. For more info and tickets: 541-552-6348 and oca.sou.edu SOU Music Recital Hall PROGRAM Welcome to the Oregon Center for the Festival Piece Craig Phillips Arts at Southern Oregon University. Organ solo (b. 1961) A Song Without Words It is an academic division of the Univer- Cello and Organ sity, but also serves a broader purpose Craig Phillips is an American composer and organist. His music as a community arts presenter, arts has been heard in many venues in the United States and partner, and producer. -

Symphony Hall. Boston Huntington and Massachusetts Avenues

SYMPHONY HALL. BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephones Ticket Office ) j g^^j^ ^ j^gj Branch Exchange I Administration Offices ) THIRTY-THIRD SEASON. 1913 AND 1914 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor ilk ^BlFSSyii WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON. MARCH 13 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, MARCH 14 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS. MANAGER 11.57 ^ii^lafta a prolonging of musical pleasure by home-firelight awaits " the owner of a "Baldwin. The strongest impressions of the concert season are linked with Baldwintone, exquisitely exploited by pianists eminent in their art. Schnitzer, Pugno, Scharwenka, Bachaus — De Pachmann! More than chance attracts the finely-gifted amateur to this keyboard. Among people who love good music, w^ho have a culti- vated know^ledge of it, and who seek the best medium for producing it, the Baldwin is chief. In such an atmosphere it is as happily "at home" as are the Preludes of Chopin, the Liszt Rhapsodies upon a virtuoso's programme. THE BOOK OF THE BALDWIN free upon request. 366 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY 1158 4 Boston Symplioey Orcliestr^ Thirty-third Season. 191 3-191 Dr. KARL MUCK. Conductor aL^ Violins. Witek, A. Roth, 0. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Noack, S. : ' ' ' ' M ." 'i ! . .v. .'.!ui.:rr-?r':'.rJ^^^^^^^^Sft YSAYE THE WORLD FAMOUS VIOLINIST AND THE CHICKERING PIANO New York City, February 5, 1913. Messrs. Chickering & Sons, Boston, Mass. Gentlemen It is a pleasure to speak of the lovely tone of the Chickering & Sons' Piano, which with its round, rich, pliable quality blends with that of my violins i'; to perfection. -

Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia Or Online at Wrti.Org

Next on Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia or online at wrti.org. Encore presentations of the entire Discoveries series every Wednesday at 7:00 p.m. on WRTI-HD2 Saturday, November 7, 2009, 5:00-6:00 p.m. Salomon Jadassohn (1831-1902). Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor (1887). Markus Becker, piano, Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Michael Sanderling. Hyperion 67636. Tr 4-6. 23:51 Gloria Coates (b.1938). Symphony No. 7 (1991). Stuttgart Philharmonic, Georg Schmöhe. CPO 999392-2. Tr 4- 6. 25:16 The 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall is on November 9th, 2009. Inspired by this historic event, the American composer Gloria Coates (who has lived in Germany for years) dedicated her seventh symphony “to those who brought down the Wall in PEACE.” Salomon Jadassohn was an eminent composer, pianist, conductor, and teacher in Germany. Although he died in 1902, his works were banned by anti-Semitic followers of Wagner in the 1930s. Fortunately, his music (ironically influenced by Richard Wagner) is beginning to be heard once again. Jadassohn attended the Leipzig Conservatory shortly after its founding by Felix Mendelssohn and eventually taught piano and composition there. He had studied piano with Ignaz Moscheles and Franz Liszt, and among his influences in composition were Liszt and Wagner. He was a well-respected teacher who produced manuals on harmony, counterpoint, and orchestration that were used for years. Grieg, Delius, and one of last month’s composers on Discoveries, George Chadwick, all studied with him. His many works, including this inventive second concerto, are wonderful examples of the Romantic idiom. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0107 Notes

TOCCATA CLASSICS Salomon JADASSOHN Piano Trios No. 1 in F major, Op. 16 No. 2 in E major, Op. 20 No. 3 in C minor, Op. 59 Syrius Trio FIRST RECORDINGS SALOMON JADASSOHN: Piano Trios Nos. 1–3 by Malcolm MacDonald Salomon Jadassohn’s name is moderately familiar to musicologists, but only because he was an important teacher, many of whose students went on to make a considerable reputation for themselves: the roll-call includes Albéniz, Alfano, Bortkiewicz, Busoni, Chadwick, Čiurlionis, Delius, Fibich, Grieg, Kajanus, Karg-Elert, Reznicek, Georg Schumann, Sinding and Weingartner. Until recently Jadassohn’s own music has been virtually ignored, but it is beginning to emerge from the shadows. "e three piano trios on this disc are not among the most important essays in the genre to emerge from nineteenth-century Germany, but they are full of highly enjoyable music, written to give pleasure, while being economically constructed with considerable skill and ingenuity. Jadassohn was born into a Jewish family in Breslau, the capital of the Prussian province of Silesia (now Wrocław in Poland), on 13 August 1831 and enrolled in the Leipzig Conservatorium in 1848, where his composition teachers were Moritz Hauptmann, Ernst Richter and Julius Rietz. He studied piano, moreover, with Beethoven’s friend and protégé Ignaz Moscheles. From 1849 to 1851, by contrast, and to the disquiet of some of his teachers, Jadassohn also became a private pupil of Franz Liszt in Weimar. He spent most of his subsequent career teaching in Leipzig. As a Jew, he was unable to apply for any of the Leipzig church-music posts that were open to other graduates from the Conservatory; instead, he worked for a synagogue and supported himself otherwise mainly as a teacher of piano. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 63,1943-1944, Trip

ffiartt^gfe l|aU • N^ut fork Fifty-eighth Season in New York k^^ '%. %. •Vh- AN'*' BOSTON "»^^M SYAPHONY ORCnCSTRS FOUNDED [N 1881 DY HENRY L. HIGGINSON SIXTY-THIRD SEASON 1943-1944 {51 Thursday Evening; March 30 Saturday Afternoon, April 1 VICTOR RED SEAL RECORDS by the Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Also Sprach Zarathustra Strauss Battle of Kershenetz Rimsky-KorsakOT Bolero Ravel Oapriccio ( Jestis Maria Sanroma, Soloist) Stravinsky Classical Symphony Prokofieff Concerto for Orchestra in D major K. P. E. Bach Concerto Grosso in D minor Vivaldi Concerto in D major (Jascha Heifetz, Soloist) Brahms Concerto No. 2 ( Jascha Heifetz, Soloist) Prokofieff Concerto No. 12 — Larghetto Handel Damnation of Faust : Minuet — Waltz — Rakoczy March Berlioz Daphnis et Chlo6 — Suite No. 2 Ravel Dublnushka Rimsky-Korsakoff "Enchanted Lake" Liadov Frtihlingsstimmen — Waltzes (Voices of Spring) Strauss Gymnop^die No. 1 Erik Satie-Debussy "Khovanstchina" Prelude Moussorgsky "La Mer*' ("The Sea") Debussy Tiast Spring Grieg "Lieutenant Kije" Suite Prokofieff Love for Three Oranges — Scherzo and March Prokofieff Maiden with the Roses Sibelius Ma Mfere L'Oye (Mother Goose) Ravel Mefisto Waltz Liszt Missa Solemnis Beethoven Pell6as et M611sande Faur6 "Peter and the Wolf Prokofieff Pictures at an Exhibition Moussorgsky-Ravel Pohjola's Daughter Sibelius "Romeo and Juliet,'* Overture-Fantasia Tchaikovsky Rosamunde — Ballet Music Schubert Sal6n Mexico, El Aaron Copland Sarabande Debussy-Ravel Song of Volga Boatmen Arr. by Stravinsky "Swanwhite" ( "The Maiden with Roses" ) Sibelius Symphony No. 1 in B-flat major ("Spring") Schumann Symphony No. 2 in D major Beethoven Symphony No. 2 In D major Sibelius Symphony No. 3 Harris Symphony No. -

Composers for the Pipe Organ from the Renaissance to the 20Th Century

Principal Composers for the Pipe Organ from the Renaissance to the 20th Century Including brief biographical and technical information, with selected references and musical examples Compiled for POPs for KIDs, the Children‘s Pipe Organ Project of the Wichita Chapter of the American Guild of Organists, by Carrol Hassman, FAGO, ChM, Internal Links to Information In this Document Arnolt Schlick César Franck Andrea & Giovanni Gabrieli Johannes Brahms Girolamo Frescobaldi Josef Rheinberger Jean Titelouze Alexandre Guilmant Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck Charles-Marie Widor Dieterich Buxtehude Louis Vierne Johann Pachelbel Max Reger François Couperin Wilhelm Middelschulte Nicolas de Grigny Marcel Dupré George Fredrick Händel Paul Hindemith Johann Sebastian Bach Jean Langlais Louis-Nicolas Clérambault Jehan Alain John Stanley Olivier Messiaen Haydn, Mozart, & Beethoven Links to information on other 20th century composers for the organ Felix Mendelssohn Young performer links Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel Pipe Organ reference sites Camille Saint-Saëns Credits for Facts and Performances Cited Almost all details in the articles below were gleaned from Wikipedia (and some of their own listed sources). All but a very few of the musical and video examples are drawn from postings on YouTube. The section of J.S. Bach also owes credit to Corliss Arnold’s Organ Literature: a Comprehensive Survey, 3rd ed.1 However, the Italicized interpolations, and many of the texts, are my own. Feedback will be appreciated. — Carrol Hassman, FAGO, ChM, Wichita Chapter AGO Earliest History of the Organ as an Instrument See the Wikipedia article on the Pipe Organ in Antiquity: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pipe_Organ#Antiquity Earliest Notated Keyboard Music, Late Medieval Period Like early music for the lute, the earliest organ music is notated in Tablature, not in the musical staff notation we know today. -

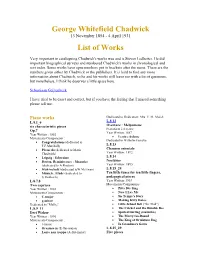

George Whitefield Chadwick List of Works

George Whitefield Chadwick 13 November 1854 - 4 April 1931 List of Works Very important in cataloguing Chadwick's works was and is Steven Ledbetter. He did important biographical surveys and numbered Chadwick's works in chronological and sort order. Some works have opus numbers put in brackets after the name. These are the numbers given either by Chadwick or the publishers. It is hard to find any more information about Chadwick, so he and his works still leave me with a lot of questions, but nonetheless, I think he deserves a little space here. Sebastiaan Geijtenbeek I have tried to be exact and correct, but if you have the feeling that I missed something please tell me. Piano works Dedicated to Dedication: Mrs. E. M. Marsh L.8.1_6 L.8.12 six characteristic pieces Overture : Melpomene Op.7 Pianoforte à 4 mains Year Written: 1887 Year Written : 1882 Movements/Components : Lento e dolente Dedicated to Wilhelm Gericke Congratulations (dedicated to F.F.Marshall) L.8.13 Please do (dedicated to Marie Chanson orientale Chadwick) Year Written : 1892 Leipzig : Scherzino L.8.14 Boston, Reminiscence : Mazurka Nocturne (dedicated to A.Preston) Year Written : 1895 Irish melody (dedicated toW.McEwen) L.8.15_24 Munich : Etude (dedicated to Ten little tunes for ten little fingers, G.Heubach) pedagogical pieces L.8.7,8 Year Written: 1903 Two caprices Movements/Components : Year Written : 1888 Pitty Itty Sing Movements/Components : Now I Lay Me C-major Sis Tempy's Story g-minor Making Kitty Dance Dedicated to "Mollie" Little School Bell ("for