Managing the Multigenerational Workplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing for Generation Z in the Workplace

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College Spring 2020 A New Generation of Workers: Preparing for Generation Z in the Workplace Kendra Harris University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons, and the Training and Development Commons Recommended Citation Harris, Kendra, "A New Generation of Workers: Preparing for Generation Z in the Workplace" (2020). Senior Theses. 335. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/335 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harris 1 Thesis Summary A new generational wave has begun to enter the workforce. The oldest members of Generation Z, those approximately at the age of 25 and below, have recently begun their careers. In the past few years, some changes have been made to work environments, like constructing gyms and daycares at workplaces, expanding the options for work at home programs, and firms hosting social events to attract top, young talent. Some of these actions were to appease Generation Y (Millennials), but some, whether the intent was known or not, will be very pleasing and beneficial to Generation Z. However, Generation Y and Z have some key differences which can create new challenges for a firm’ managers and human resource departments. For example, Generation Z desires to complete their work in the correct way to please their managers, so exceptional training would be strongly recommended for Generation Z to be confident in their work. -

On Education

DEBATES ON EDUCATION www.debats.cat/en www.debats.cat/en Debates on Education|45 Building a School for the Digital Natives Generation Kirsti Lonka An initiative of In collaboration with Building a School for the Digital Natives Generation Debates on education | 45 DEBATES ON EDUCATION www.debats.cat/en 34 Building a School for the Digital Natives Generation How canKirsti we buildLonka student engagement and an educational community? Valerie Hannon How can we build student engagement and an educational community? Debats on education | 31 Debates on education | 45 An initiative of In collaboration with Universitat Oberta de Catalunya www.uoc.edu Transcript of Kirsti Lonka keynote speech at MACBA Auditorium. Barcelona, January 31, 2017. Debates on Education. All contents of Debates on Education may be found on line at www.debats.cat/en (guests, contents, conferences audio, video and publications). © Fundació Jaume Bofill and UOC, 2017 Provença, 324 08037 Barcelona [email protected] www.fbofill.cat This work is licensed under a Creative Commons “Attribution-ShareAlike International”. The commercial use of this work and possible derivatives is permitted. The distribution of the latter requires a license, identical to the one that regulates the original work. First Edition: May 2017 Author: Kirsti Lonka Publishing Coordinator: Valtencir Mendes Publishing Technical Coordinator: Anna Sadurní Publishing revision: Samuel Blàzquez Graphic Design: Amador Garrell ISBN: 978-84-946592-4-9 Index Introduction ..................................................................... 5 How to create new cultures for study and academic work? ............................................................... 7 How to prevent boredom and burn out and support the new generation? ........................................................ 10 What is engagement? ...................................................... 12 The digital challenge ...................................................... -

Generation Z and Implications for Counseling

Generation Z and Implications for Counseling Slameto Satya Wacana Christian University [email protected] Abstract Generation Z is a common name in the US and other Western countries for the group of people born from the second half of the 1990s through the late of the 2000s early 2010’s, a span of 15-20 years in the very late of the 20th Century and very early 21st Century. Gneration Z has behavioral and personality characteristics that are different from previuos generations. Characteristics of Generation Z are: 1) Fluent Technology, they are the “digital generation” who can acces the information as quickly and as easily possible, either for educational purposes or their interests in their daily lives. 2) Social, they are very intensely communicated with peers through various networking sites. They also tend to be tolerant to cultural differences and are very concerned with the environment. 3) Multitasking, are familiar with a variety of activities, read, talk, watch, or listen to music at the same time, wanting things to be done simultaneously and fast paced run. These characteristics have two opposite sides, provides benefits for themselves and their community, they can harm themselves and their environment. The presence of Generation Z has implications for education and counseling, namely: 1) Teachers and counselors are to guide and facilitate their development and use technology appropriately and wisely. 2) Teachers and counselors are to develop a Learning-Centered Approach Model in order that students are able to understand complex and dynamic world phenomenon. 3) Teachers and counselors are to utlize Face Book to support the effectiveness of guidance and counseling services in school. -

Developing the Next Generation

Learning to Work Research report June 2015 DEVELOPING THE NEXT GENERATION TODAY’S YOUNG PEOPLE, TOMORROW’S WORKFORCE The CIPD is the professional body for HR and people development. The not-for-profit organisation champions better work and working lives and has been setting the benchmark for excellence in people and organisation development for more than 100 years. It has more than 135,000 members across the world, provides thought leadership through independent research on the world of work, and offers professional training and accreditation for those working in HR and learning and development. 1 Developing the next generation Developing the next generation Research report Contents Foreword 2 Introduction 3 1 What does existing research tell us? 6 2 Building the business case for investing in development 9 3 Workplace skills 14 4 Development methods 19 5 Generational learning preferences 23 Conclusion 27 References 28 Acknowledgements This report was written by Ruth Stuart, Research Adviser at the CIPD. The research was supported by Katerina Rüdiger, Katherine Garrett and Stella Martorana at the CIPD. We are indebted to all of the individuals in the case study organisations who took part in the research through interviews and focus groups. In particular we would like to thank: Temi Akinmoladun – Apprentice, Barclays Graham Salisbury – Head of Human Resources, ActionAid Shajjad Ali – Apprentice, ActionAid Susithaa Sathiyamoorthy – Apprentice, ActionAid Sarah Bampton – Talent Programme Manager, Fujitsu Dan Snowdon – Industrial placement, -

Softening Power: Cuteness As Organizational Communication Strategy in Japan and the West

© 2018 Journal of International and Advanced Japanese Studies Vol. 10, February 2018, pp. 39-55 Master’s and Doctoral Programs in International and Advanced Japanese Studies Iain MACPHERSON & Teri Jane BRYANT Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Tsukuba Article Softening Power: Cuteness as Organizational Communication Strategy in Japan and the West Iain MACPHERSON MacEwan University, Faculty of Fine Arts and Communication, Assistant Professor Teri Jane BRYANT Haskayne School of Business, University of Calgary, Associate Professor Emerita This paper describes the use of cute communications (visual or verbal, and in various media) as an organizational communication strategy prevalent in Japan and emerging in western countries. Insights are offered for the use of such communications and for the understanding/critique thereof. It is first established that cuteness in Japan–kawaii–is chiefly studied as a sociocultural or psychological phenomenon, with too little analysis of its near-omnipresent institutionalization and conveyance as mass media. The following discussion clarifies one reason for this gap in research–the widespread conflation of ʻorganizational communication’ with advertising/branding, notwithstanding the variety of other messaging–public relations, employee communications, public service announcements, political campaigns–conveyed through cuteness by Japanese institutions. It is then argued that what few theorizations exist of organizational kawaii communications overemphasize their negative aspects or potentials, attributing to them both too much iniquity and too much influence. Outside of Japan studies, there is even less up-to-date scholarship on organizational cuteness, critical or otherwise. And there are no such studies at all, whether focused on Japan or elsewhere, that integrate intercultural insights. -

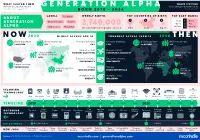

Gen Alpha 2020

WHAT SHAPED THEM THEIR FUTURE Millennial parents (Generation Y) GENERATION ALPHA Older siblings to Generation Beta Born 1980-1994 — aged 26-40 BORN 2010 2024 Born 2025-2039 LABELS WEEKLY BIRTHS TOP COUNTRIES OF BIRTH TOP BABY NAMES ABOUT The Alphas 1 2 3 GENERATION Generation glass Upagers Noah 1 Olivia 2,740,000 Oliver 2 Ava ALPHA William 3 Amelia Multi-modals Global Gen Generation Alphas born globally each week India China Nigeria NOW2020 OLDEST ALPHAS ARE 10 YOUNGEST ALPHAS TURN 25 2050 THEN Global population Global median age University graduates University graduates Global population Global median age 7.8 BILLION 30.9 1 IN 3 1 IN 2 9.8 BILLION 36.1 Business context Business context Largest population FREQUENT DISRUPTION CONTINUOUS VOLATILITY Largest economy growth by continent CHINA ASIA Education outcomes Education outcomes EMPLOYABILITY ADAPTABILITY Largest economy Largest population growth by continent UNITED STATES Training Training Largest population AFRICA Largest CHINA QUALIFICATIONS MICROCREDENTIALS population INDIA Workplace focus Workplace focus DIVERSITY WELLBEING INCOMING TECHNOLOGY Autonomous Quantum Aerial iPad Instagram GoPro 3D Google glass Apple Tesla Smart Siri HERO3 printers watch Powerwall Fortnite speakers AirPods 5G Biometrics vehicles computing ridesharing TIMELINE 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 Street Fax Landline Car key - Desktop Credit Analogue OUTGOING Myspace directory Pager MP3 player Blackberry machine phone CD/DVD GPS unit ignition Textbooks computer cards -

Generation Z's Positive and Negative Attributes and the Impact On

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2019 Generation Z's Positive and Negative Attributes and the Impact on Empathy After a Community- Based Learning Experience Amanda Nicole Moscrip University of North Florida Suggested Citation Moscrip, Amanda Nicole, "Generation Z's Positive and Negative Attributes and the Impact on Empathy After a Community-Based Learning Experience" (2019). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 908. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/908 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2019 All Rights Reserved GENERATION Z’S POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE ATTRIBUTES AND THE IMPACT ON EMPATHY AFTER A COMMUNITY-BASED LEARNING EXPERIENCE by Amanda Nicole Moscrip A thesis submitted to the Department of Psychology in partial fulfillment to the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Psychological Science UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES August, 2019 Unpublished work © Amanda Nicole Moscrip GEN Z’S ATTRIBUTES AND THE IMPACT ON EMPATHY AFTER A CBL EXPERIENCE ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my family and friends for all of the support throughout this journey. I would like to extend a special thank you to my mother Teresa Moscrip, my father Michael Moscrip, and my brothers Tyler and Matthew Moscrip for all of the unconditional love and encouragement. I would like to thank my friends Evan Wagoner, Michelle Boss, and Anna Lall for always supporting me. -

'True Gen': Generation Z and Its Implication for Companies

‘True Gen’: Generation Z and its implications for companies The influence of Gen Z—the first generation of true digital natives—is expanding. Tracy Francis and Fernanda Hoefel NOVEMEBER 2018 • CONSUMER PACKAGED GOODS © FG Trade/Getty Images Long before the term “influencer” was coined, us, Gen Z is “True Gen.” In contrast, the previous young people played that social role by creating generation—the millennials, sometimes called the and interpreting trends. Now a new generation of “me generation”—got its start in an era of economic influencers has come on the scene. Members of prosperity and focuses on the self. Its members Gen Z—loosely, people born from 1995 to 2010— are more idealistic, more confrontational, and less are true digital natives: from earliest youth, they willing to accept diverse points of view. have been exposed to the internet, to social networks, and to mobile systems. That context Such behaviors influence the way Gen Zers view has produced a hypercognitive generation very consumption and their relationships with brands. comfortable with collecting and cross-referencing Companies should be attuned to three implications many sources of information and with integrating for this generation: consumption as access rather virtual and offline experiences. than possession, consumption as an expression of individual identity, and consumption as a matter As global connectivity soars, generational shifts of ethical concern. Coupled with technological could come to play a more important role in setting advances, this generational shift is transforming behavior than socioeconomic differences do. Young the consumer landscape in a way that cuts across people have become a potent influence on people all socioeconomic brackets and extends beyond of all ages and incomes, as well as on the way those Gen Z, permeating the whole demographic pyramid. -

The New Generation of Students How Colleges Can Recruit, Teach, and Serve Gen Z

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The New Generation of Students How colleges can recruit, teach, and serve Gen Z new generation of students has arrived on college campuses. Known as Gen Z, this cohort marks a break from even the recent past in terms of diversity, attitudes about money, and use of technology. Now, institutions that have spent the last several years catering to millennials must pivot to appeal to the traditional-age students poised to Aenter higher education over the next decade and a half. Gen Z is the most diverse generation as this new generation coincides in modern American history, and its with a shrinking pool of high-school members are attentive to inclusion across graduates and increased expectations for race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and student success. To help colleges better gender identity. The Great Recession understand this new cohort, The Chronicle and its aftermath focused Gen Zers on of Higher Education has published its the value and relevance of a degree. latest in-depth report, The New Generation The purpose of college for them is to of Students: How colleges can recruit, help launch a career. Gen Zers also see teach, and serve Gen Z. This executive technology as an extension of themselves summary highlights how the report, with respect to how they communicate, which was published in September, consume information, and learn. presents insights into the mind-sets and No generation is a monolith, and motivations of Gen Zers and describes research on Gen Z is just emerging. But how colleges can best reach and serve this campus leaders must pay attention, new generation of learners. -

Recognizing the Vulnerability of Generation Z to Economic and Social Risks

Blagica Novkovska and Gordana Serafimovic. 2018. Recognizing the Vulnerability of Generation Z to Economic and Social Risks. UTMS Journal of Economics 9 (1): 29–37. Preliminary communication (accepted April 3, 2018) RECOGNIZING THE VULNERABILITY OF GENERATION Z TO ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RISKS Blagica Novkovska1 Gordana Serafimovic Abstract Generation Z, known also as “Net generation” and “Digital natives”, is of particular interest for researchers do to its specifics originating from the changes caused in the everyday’s live by the new technologies. This cohort is known to be highly vulnerable to several economic and social risks, depending on the characteristics of the society where they live. In this paper the socio-economic situation of youth in some small countries with different level of development is studied. Particular importance is paid to the criminality as a risk factor for Generation Z. The case of Macedonia has been studied in details, using the relevant data for the period from 2007 to 2016. Based on the use of a multivariate linear regression model it has been found that the criminality is strongly related to the size of NEET (part of the cohort that is Not in Education, Employment or Training). Keywords: youth, NEET, poverty, labour market transitions. Jel Classification: C22; C52; E24; I24; J29 INTRODUCTION A lot of different attempts were made in the literature to define Generation Z (Pal 2013). According to some approaches, members of Generation Z were born after 1995 (Grail Research 2011) and 1996. Oblinger and Oblinger (2005) call this group post- millenarians, but it is also called “Facebook Generation” (Prensky 2001), zappers which means switchers, “Instant online” group, “dotcom” kids, net generation, iGeneration. -

Generation Z: Step Aside Millennials Sorry Millennials, Your Time in the Limelight Is Over

Barclays Research Highlights: Sustainable & Thematic Investing Generation Z: Step aside Millennials Sorry Millennials, your time in the limelight is over. Make way for the new kids on the block - Generation Z - a generational cohort born between 1995 and 2009, and larger in size than the Millennials (1980-1994). The current fixation with Millennials makes them the most studied generation, which in turn has caused the use of this term to simplify to a label for anyone that may be young today. The irony here is that Millennials are not necessarily young anymore and we run the risk of overlooking the next cohort - Generation Z - who are now coming of age. For more information about Barclays Research’s offering, including coverage of this subject, please contact: [email protected] Completed: dd-Mmm-yy, HH:mm GMT Released: dd-Mmm-yy, HH:mm GMT Restricted -External The word ‘Millennial’ is overused and frequently used as a synonym for being young. Incorrect use of the label for all young people means that weGeneration run the risk Z: ofStep overlooking aside Millennials the next generational cohort who Millennialhave their Fixation own Fatigue set of values — cue Generation Z. Sorry Millennials, your time in the limelight is over. Make way for the new kids on the block — Generation Z — a generational cohort born between 1995 and 2009, and larger in size than the Millennials (1980–1994). The current fixation with Millennials makes them the most studied generation, which in turn has caused the use of this term to simplify to a label for anyone that Pre 1924 100+ may be young today. -

Characterizing Generation Z and Its Implications to Booking Practices in the Hotel Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by School of Hotel Administration, Cornell University Cornell University School of Hotel Administration The Scholarly Commons SHA Latin Honors Theses School of Hotel Administration Collection Spring 2019 Characterizing Generation Z and its Implications to Booking Practices in the Hotel Industry Sitara Kishore Cornell University School of Hotel Administration Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/honorstheses Part of the Hospitality Administration and Management Commons Custom Citation Kishore, S. (2019). Characterizing Generation Z and its implications to booking practices in the hotel industry. [Electronic version]. Available from Cornell University, School of Hotel Administration site: https://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/honorstheses/9 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Hotel Administration Collection at The Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in SHA Latin Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. Characterizing Generation Z and its Implications to Booking Practices in the Hotel Industry Abstract In an evaluation of preceding research, this study explores the characterization of Generation Z and, through a carefully designed questionnaire, its impact on consumer booking practices to prepare the hotel industry to better adapt to the incoming generation of travelers. Informed by the literature evaluated, the survey asks questions to (1) characterize the travel behavior of each participant, (2) ascertain the relative importance of multiple identified factors to their booking decision, and (3) characterize their individual profile.