JOURNAL of LANGUAGE and LINGUISTIC STUDIES Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing for Generation Z in the Workplace

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College Spring 2020 A New Generation of Workers: Preparing for Generation Z in the Workplace Kendra Harris University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons, and the Training and Development Commons Recommended Citation Harris, Kendra, "A New Generation of Workers: Preparing for Generation Z in the Workplace" (2020). Senior Theses. 335. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/335 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harris 1 Thesis Summary A new generational wave has begun to enter the workforce. The oldest members of Generation Z, those approximately at the age of 25 and below, have recently begun their careers. In the past few years, some changes have been made to work environments, like constructing gyms and daycares at workplaces, expanding the options for work at home programs, and firms hosting social events to attract top, young talent. Some of these actions were to appease Generation Y (Millennials), but some, whether the intent was known or not, will be very pleasing and beneficial to Generation Z. However, Generation Y and Z have some key differences which can create new challenges for a firm’ managers and human resource departments. For example, Generation Z desires to complete their work in the correct way to please their managers, so exceptional training would be strongly recommended for Generation Z to be confident in their work. -

On Education

DEBATES ON EDUCATION www.debats.cat/en www.debats.cat/en Debates on Education|45 Building a School for the Digital Natives Generation Kirsti Lonka An initiative of In collaboration with Building a School for the Digital Natives Generation Debates on education | 45 DEBATES ON EDUCATION www.debats.cat/en 34 Building a School for the Digital Natives Generation How canKirsti we buildLonka student engagement and an educational community? Valerie Hannon How can we build student engagement and an educational community? Debats on education | 31 Debates on education | 45 An initiative of In collaboration with Universitat Oberta de Catalunya www.uoc.edu Transcript of Kirsti Lonka keynote speech at MACBA Auditorium. Barcelona, January 31, 2017. Debates on Education. All contents of Debates on Education may be found on line at www.debats.cat/en (guests, contents, conferences audio, video and publications). © Fundació Jaume Bofill and UOC, 2017 Provença, 324 08037 Barcelona [email protected] www.fbofill.cat This work is licensed under a Creative Commons “Attribution-ShareAlike International”. The commercial use of this work and possible derivatives is permitted. The distribution of the latter requires a license, identical to the one that regulates the original work. First Edition: May 2017 Author: Kirsti Lonka Publishing Coordinator: Valtencir Mendes Publishing Technical Coordinator: Anna Sadurní Publishing revision: Samuel Blàzquez Graphic Design: Amador Garrell ISBN: 978-84-946592-4-9 Index Introduction ..................................................................... 5 How to create new cultures for study and academic work? ............................................................... 7 How to prevent boredom and burn out and support the new generation? ........................................................ 10 What is engagement? ...................................................... 12 The digital challenge ...................................................... -

The 'Digital Native' and 'Digital Immigrant': a Dangerous Opposition

The ‘digital native’ and ‘digital immigrant’: a dangerous opposition Siân Bayne and Jen Ross University of Edinburgh This paper is presented at the Annual Conference of the Society for Research into Higher Education (SRHE) December 2007. Introduction The distinction between the digital ‘native’ and the digital ‘immigrant’ has become a commonly- accepted trope within higher education and its broader cultural contexts, as a way of mapping and understanding the rapid technological changes which are re-forming our learning spaces, and ourselves as subjects in the digital age. Young people have grown up with computers and the internet, the argument goes, and are naturally proficient with new digital technologies and spaces, while older people will always be a step behind/apart in their dealings with the digital. What is more, young learners’ immersion in digital technologies creates in them a radically different approach to learning, one which is concerned above all with speed of access, instant gratification, impatience with linear thinking and the ability to multi-task. Teachers, we are told, have a duty to adapt their methods to this new way of learning – are required, in fact, to re-constitute themselves according to the terms of the ‘native’ in order to remain relevant and, presumably, employable (for example Prensky 2001, Oblinger 2003, Long 2005, Barnes et al 2007, Thompson 2007). It is no doubt the case that when we work in internet environments, we work with technological spaces which are highly volatile, and which offer us new and potentially radical ways of communicating, representing and constituting knowledge and selfhood. Within such potentially disorienting spaces, the rhetoric of the digital ‘native’ allows us to structure and contain our understanding of their implications, positioning young learners as subjects ‘at one’ with the digital environment in a way which older users – teachers, ‘immigrants’ – can never be. -

Millennial Leadership in Law Schools: Essays on Disruption, Innovation, and the Future

Millennial Leadership in Law Schools: Essays on Disruption, Innovation, and the Future Edited By: Ashley Krenelka Chase Associate Director, Dolly & Homer Hand Law Library Coordinator for Legal Practice Technology & Instructor of Law; Stetson University College of Law Includes contributions from more than 20 professionals! • Explores the role Millennials will play in shaping the future of legal education • Gain insight into Millennials’ way of thinking and learn how to mentor and guide them to be successful • Perfect for law school administrators, faculty, staff members, and students from all generations About This Title This book explores the role millennials will play—as faculty, administrators, or staff members—in shaping the future of legal education, and what the academy can do to embrace the millennial generation as colleagues, not students. This book can be used to understand, guide, engage, mentor, and work with Millennials to shape the next generation of excellent law school leaders. • Section I: These chapters focus on the culture of law schools, and the need to embrace a new, forward-thinking and innovative way of defining what law schools are and do and how we educate students. • Section II: In section two, the authors focus on relationships: the relationships Millennials in the academy have with ourselves, our institutions, and the community. • Section III: This section includes chapters that detail how Millennial leaders work in the classroom, how they use things like feedback and assessment to change the dynamic in the classroom and to innovate law school pedagogy to educate well- rounded lawyers. • Section IV: These chapter are an essential read for anyone who spends time thinking about the current legal economy and law schools’ roles in educating practice-ready lawyers. -

On Digital Immigrants and Digital Natives: How the Digital Divide Affects Families, Educational Institutions, and the Workplace by Ofer Zur, Ph.D

On Digital Immigrants and Digital Natives: How the Digital Divide Affects Families, Educational Institutions, and the Workplace By Ofer Zur, Ph.D. (Digital Immigrant) & Azzia Zur, B.A. (Digital Native) "Digital native" is a term for people born in the digital era, i.e., Generation X and younger. This group is also referred to as the "iGeneration" or is described as having been born with "digital DNA." In contrast, the term "digital immigrant" refers to those born before about 1964 and who grew up in a pre-computer world. The terms "digital immigrants" and "digital natives" were popularized and elaborated upon by Dr. Mark Prensky (2001) and critiqued for their validity and usefulness by Harding (2010) among others. In the most general terms, digital natives speak and breathe the language of computers and the culture of the web into which they were born, while digital immigrants will never deal with technology as naturally as those who grew up with it. Not all Digital Immigrants and Digital Natives are Created Equal It is important to realize that not all digital immigrants and not all digital natives are created equal. The native/immigrant divide is one of generations - people were either born in the digital era or they were not (Rosen, 2010; Zur & Zur, 2011). While most digital natives are tech-savvy by virtue of their being born around technology, others do not have a knack for technology and computers, or even an interest or inclination to learn more. Digital immigrants are also clearly a highly diverse group in terms of their attitudes and capacities in regard to digital technologies. -

Digital Natives

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Education - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2012 Digital natives Sue Bennett University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/edupapers Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Sue: Digital natives 2012, 212-219. https://ro.uow.edu.au/edupapers/1049 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Chapter accepted for publication in The Encyclopedia of Cyber Behavior, forthcoming from IGI Global. Final draft accepted 18 August 2011. Digital Natives Sue Bennett Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong, Australia ABSTRACT The term ‘digital native’ was popularized by Prensky (2001) as a means to distinguish young people who were highly technologically literate and engaged. His central claim was that because of immersion in digital technologies from birth younger people think and learn differently from older generations. Tapscott (1998) proposed a similar idea, calling it ‘The Net Generation’, and there have been numerous labels applied to the same supposed phenomena. Recent research has revealed that the term is misapplied when used to generalize about an entire generation, and instead indicates that only a small sub-set of the population fits this characterization. This research shows significant diversity in the technology skills, knowledge and interests of young people, and suggests that there are important ‘digital divides’ which are ignored by the digital native concept. This chapter synthesizes key findings from Europe, North America and Australia and predicts future directions for research in this area. -

Generation Z and Implications for Counseling

Generation Z and Implications for Counseling Slameto Satya Wacana Christian University [email protected] Abstract Generation Z is a common name in the US and other Western countries for the group of people born from the second half of the 1990s through the late of the 2000s early 2010’s, a span of 15-20 years in the very late of the 20th Century and very early 21st Century. Gneration Z has behavioral and personality characteristics that are different from previuos generations. Characteristics of Generation Z are: 1) Fluent Technology, they are the “digital generation” who can acces the information as quickly and as easily possible, either for educational purposes or their interests in their daily lives. 2) Social, they are very intensely communicated with peers through various networking sites. They also tend to be tolerant to cultural differences and are very concerned with the environment. 3) Multitasking, are familiar with a variety of activities, read, talk, watch, or listen to music at the same time, wanting things to be done simultaneously and fast paced run. These characteristics have two opposite sides, provides benefits for themselves and their community, they can harm themselves and their environment. The presence of Generation Z has implications for education and counseling, namely: 1) Teachers and counselors are to guide and facilitate their development and use technology appropriately and wisely. 2) Teachers and counselors are to develop a Learning-Centered Approach Model in order that students are able to understand complex and dynamic world phenomenon. 3) Teachers and counselors are to utlize Face Book to support the effectiveness of guidance and counseling services in school. -

Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants, Digital Learners: an International Empirical Integrative Review of the Literature

Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants, Digital Learners: An International Empirical Integrative Review of the Literature Theodore B. Creighton American College of Education The author, preparing for a new position as a doctoral research faculty at the American College of Education (ACE), conducted an extensive integrated literature review of “digital natives” and related terms. Focus of the review was directed specifically around digital learners defined as those born between 1980 and 1994. The results clearly revealed a variety of definitions for “digital natives” and “digital immigrants” with no specific clarification or research-based rationale. In addition, strong evidence points toward little connection between a student’s age and digital skills and increased learning. Much of the research suggests that students’ digital competence may be much lower than their “digital professors.” ICPEL Education Leadership Review, Vol. 19, No. 1– December, 2018 ISSN: 1532-0723 © 2018 International Council of Professors of Educational 132 The term Digital Native seems to have first appeared in the literature in the late 1990s and is mostly accredited to Prensky (2001a, 2001b) and Tapscott (1998, 2009). Students (called digital natives) are those born roughly between 1980 and 1994, and represent the first generation to grow up with new technology and have been characterized by their familiarity with and confidence in, with respect to Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). They have spent most of their lives surrounded with digital communication technology (Gallardo-Echenique, Marques-Molas, Bullen, & Strijbos, 2015). Modern day students in kindergarten through college have spent their lives surrounded by computers, video games, cell phones, and other digital products. -

Developing the Next Generation

Learning to Work Research report June 2015 DEVELOPING THE NEXT GENERATION TODAY’S YOUNG PEOPLE, TOMORROW’S WORKFORCE The CIPD is the professional body for HR and people development. The not-for-profit organisation champions better work and working lives and has been setting the benchmark for excellence in people and organisation development for more than 100 years. It has more than 135,000 members across the world, provides thought leadership through independent research on the world of work, and offers professional training and accreditation for those working in HR and learning and development. 1 Developing the next generation Developing the next generation Research report Contents Foreword 2 Introduction 3 1 What does existing research tell us? 6 2 Building the business case for investing in development 9 3 Workplace skills 14 4 Development methods 19 5 Generational learning preferences 23 Conclusion 27 References 28 Acknowledgements This report was written by Ruth Stuart, Research Adviser at the CIPD. The research was supported by Katerina Rüdiger, Katherine Garrett and Stella Martorana at the CIPD. We are indebted to all of the individuals in the case study organisations who took part in the research through interviews and focus groups. In particular we would like to thank: Temi Akinmoladun – Apprentice, Barclays Graham Salisbury – Head of Human Resources, ActionAid Shajjad Ali – Apprentice, ActionAid Susithaa Sathiyamoorthy – Apprentice, ActionAid Sarah Bampton – Talent Programme Manager, Fujitsu Dan Snowdon – Industrial placement, -

Softening Power: Cuteness As Organizational Communication Strategy in Japan and the West

© 2018 Journal of International and Advanced Japanese Studies Vol. 10, February 2018, pp. 39-55 Master’s and Doctoral Programs in International and Advanced Japanese Studies Iain MACPHERSON & Teri Jane BRYANT Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Tsukuba Article Softening Power: Cuteness as Organizational Communication Strategy in Japan and the West Iain MACPHERSON MacEwan University, Faculty of Fine Arts and Communication, Assistant Professor Teri Jane BRYANT Haskayne School of Business, University of Calgary, Associate Professor Emerita This paper describes the use of cute communications (visual or verbal, and in various media) as an organizational communication strategy prevalent in Japan and emerging in western countries. Insights are offered for the use of such communications and for the understanding/critique thereof. It is first established that cuteness in Japan–kawaii–is chiefly studied as a sociocultural or psychological phenomenon, with too little analysis of its near-omnipresent institutionalization and conveyance as mass media. The following discussion clarifies one reason for this gap in research–the widespread conflation of ʻorganizational communication’ with advertising/branding, notwithstanding the variety of other messaging–public relations, employee communications, public service announcements, political campaigns–conveyed through cuteness by Japanese institutions. It is then argued that what few theorizations exist of organizational kawaii communications overemphasize their negative aspects or potentials, attributing to them both too much iniquity and too much influence. Outside of Japan studies, there is even less up-to-date scholarship on organizational cuteness, critical or otherwise. And there are no such studies at all, whether focused on Japan or elsewhere, that integrate intercultural insights. -

Gen Alpha 2020

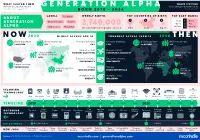

WHAT SHAPED THEM THEIR FUTURE Millennial parents (Generation Y) GENERATION ALPHA Older siblings to Generation Beta Born 1980-1994 — aged 26-40 BORN 2010 2024 Born 2025-2039 LABELS WEEKLY BIRTHS TOP COUNTRIES OF BIRTH TOP BABY NAMES ABOUT The Alphas 1 2 3 GENERATION Generation glass Upagers Noah 1 Olivia 2,740,000 Oliver 2 Ava ALPHA William 3 Amelia Multi-modals Global Gen Generation Alphas born globally each week India China Nigeria NOW2020 OLDEST ALPHAS ARE 10 YOUNGEST ALPHAS TURN 25 2050 THEN Global population Global median age University graduates University graduates Global population Global median age 7.8 BILLION 30.9 1 IN 3 1 IN 2 9.8 BILLION 36.1 Business context Business context Largest population FREQUENT DISRUPTION CONTINUOUS VOLATILITY Largest economy growth by continent CHINA ASIA Education outcomes Education outcomes EMPLOYABILITY ADAPTABILITY Largest economy Largest population growth by continent UNITED STATES Training Training Largest population AFRICA Largest CHINA QUALIFICATIONS MICROCREDENTIALS population INDIA Workplace focus Workplace focus DIVERSITY WELLBEING INCOMING TECHNOLOGY Autonomous Quantum Aerial iPad Instagram GoPro 3D Google glass Apple Tesla Smart Siri HERO3 printers watch Powerwall Fortnite speakers AirPods 5G Biometrics vehicles computing ridesharing TIMELINE 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 Street Fax Landline Car key - Desktop Credit Analogue OUTGOING Myspace directory Pager MP3 player Blackberry machine phone CD/DVD GPS unit ignition Textbooks computer cards -

Generation Z's Positive and Negative Attributes and the Impact On

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2019 Generation Z's Positive and Negative Attributes and the Impact on Empathy After a Community- Based Learning Experience Amanda Nicole Moscrip University of North Florida Suggested Citation Moscrip, Amanda Nicole, "Generation Z's Positive and Negative Attributes and the Impact on Empathy After a Community-Based Learning Experience" (2019). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 908. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/908 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2019 All Rights Reserved GENERATION Z’S POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE ATTRIBUTES AND THE IMPACT ON EMPATHY AFTER A COMMUNITY-BASED LEARNING EXPERIENCE by Amanda Nicole Moscrip A thesis submitted to the Department of Psychology in partial fulfillment to the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Psychological Science UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES August, 2019 Unpublished work © Amanda Nicole Moscrip GEN Z’S ATTRIBUTES AND THE IMPACT ON EMPATHY AFTER A CBL EXPERIENCE ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my family and friends for all of the support throughout this journey. I would like to extend a special thank you to my mother Teresa Moscrip, my father Michael Moscrip, and my brothers Tyler and Matthew Moscrip for all of the unconditional love and encouragement. I would like to thank my friends Evan Wagoner, Michelle Boss, and Anna Lall for always supporting me.