We Consider the Ordinary Differential Equation Model of the Metal Rolling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Diversity of Dolichol-Linked Precursors to Asn-Linked Glycans Likely Results from Secondary Loss of Sets of Glycosyltransferases

The diversity of dolichol-linked precursors to Asn-linked glycans likely results from secondary loss of sets of glycosyltransferases John Samuelson*†, Sulagna Banerjee*, Paula Magnelli*, Jike Cui*, Daniel J. Kelleher‡, Reid Gilmore‡, and Phillips W. Robbins* *Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, Boston University Goldman School of Dental Medicine, 715 Albany Street, Boston, MA 02118-2932; and ‡Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA 01665-0103 Contributed by Phillips W. Robbins, December 17, 2004 The vast majority of eukaryotes (fungi, plants, animals, slime mold, to N-glycans of improperly folded proteins, which are retained in and euglena) synthesize Asn-linked glycans (Alg) by means of a the ER by conserved glucose-binding lectins (calnexin͞calreticulin) lipid-linked precursor dolichol-PP-GlcNAc2Man9Glc3. Knowledge of (13). Although the Alg glycosyltransferases in the lumen of ER this pathway is important because defects in the glycosyltrans- appear to be eukaryote-specific, archaea and Campylobacter sp. ferases (Alg1–Alg12 and others not yet identified), which make glycosylate the sequon Asn and͞or contain glycosyltransferases dolichol-PP-glycans, lead to numerous congenital disorders of with domains like those of Alg1, Alg2, Alg7, and STT3 (1, 14–16). glycosylation. Here we used bioinformatic and experimental Protists, unicellular eukaryotes, suggest three notable exceptions methods to characterize Alg glycosyltransferases and dolichol- to the N-linked glycosylation path described in yeast and animals PP-glycans of diverse protists, including many human patho- (17). First, the kinetoplastid Trypanosoma cruzi (cause of Chagas gens, with the following major conclusions. First, it is demon- myocarditis), fails to glucosylate the dolichol-PP-linked precursor strated that common ancestry is a useful method of predicting and so makes dolichol-PP-GlcNAc2Man9 (18). -

Physical Interactions Between the Alg1, Alg2, and Alg11 Mannosyltransferases of the Endoplasmic Reticulum

Glycobiology vol. 14 no. 6 pp. 559±570, 2004 DOI: 10.1093/glycob/cwh072 Advance Access publication on March 24, 2004 Physical interactions between the Alg1, Alg2, and Alg11 mannosyltransferases of the endoplasmic reticulum Xiao-Dong Gao2, Akiko Nishikawa1, and Neta Dean1 begins on the cytosolic face of the ER, where seven sugars (two N-acetylglucoseamines and five mannoses) are added 1Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Institute for Cell and Developmental Biology, State University of New York, Stony Brook, sequentially to dolichyl phosphate on the outer leaflet of NY 11794-5215, and 2Research Center for Glycoscience, National the ER, using nucleotide sugar donors (Abeijon and Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Tsukuba Hirschberg, 1992; Perez and Hirschberg, 1986; Snider and Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/glycob/article/14/6/559/638968 by guest on 30 September 2021 Central 6, 1-1 Higashi, Tsukuba 305-8566, Japan Rogers, 1984). After a ``flipping'' or translocation step, the Received on January 26, 2004; revised on March 2, 2004; accepted on last seven sugars (four mannoses and three glucoses) are March 2, 2004 added within the lumen of the ER, using dolichol-linked sugar donors (Burda and Aebi, 1999). Once assembled, the The early steps of N-linked glycosylation involve the synthesis oligosaccharide is transferred from the lipid to nascent of a lipid-linked oligosaccharide, Glc3Man9GlcNAc2-PP- protein in a reaction catalyzed by oligosaccharyltransferase. dolichol, on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. After removal of terminal glucoses and a single mannose, Prior to its lumenal translocation and transfer to nascent nascent glycoproteins bearing the N-linked Man8GlcNAc2 glycoproteins, mannosylation of Man5GlcNAc2-PP-dolichol core can exit the ER to the Golgi, where this core may is catalyzed by the Alg1, Alg2, and Alg11 mannosyltrans- undergo further carbohydrate modifications. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Yeast Genome Gazetteer P35-65

gazetteer Metabolism 35 tRNA modification mitochondrial transport amino-acid metabolism other tRNA-transcription activities vesicular transport (Golgi network, etc.) nitrogen and sulphur metabolism mRNA synthesis peroxisomal transport nucleotide metabolism mRNA processing (splicing) vacuolar transport phosphate metabolism mRNA processing (5’-end, 3’-end processing extracellular transport carbohydrate metabolism and mRNA degradation) cellular import lipid, fatty-acid and sterol metabolism other mRNA-transcription activities other intracellular-transport activities biosynthesis of vitamins, cofactors and RNA transport prosthetic groups other transcription activities Cellular organization and biogenesis 54 ionic homeostasis organization and biogenesis of cell wall and Protein synthesis 48 plasma membrane Energy 40 ribosomal proteins organization and biogenesis of glycolysis translation (initiation,elongation and cytoskeleton gluconeogenesis termination) organization and biogenesis of endoplasmic pentose-phosphate pathway translational control reticulum and Golgi tricarboxylic-acid pathway tRNA synthetases organization and biogenesis of chromosome respiration other protein-synthesis activities structure fermentation mitochondrial organization and biogenesis metabolism of energy reserves (glycogen Protein destination 49 peroxisomal organization and biogenesis and trehalose) protein folding and stabilization endosomal organization and biogenesis other energy-generation activities protein targeting, sorting and translocation vacuolar and lysosomal -

Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation from a Neurological Perspective

brain sciences Review Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation from a Neurological Perspective Justyna Paprocka 1,* , Aleksandra Jezela-Stanek 2 , Anna Tylki-Szyma´nska 3 and Stephanie Grunewald 4 1 Department of Pediatric Neurology, Faculty of Medical Science in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, 40-752 Katowice, Poland 2 Department of Genetics and Clinical Immunology, National Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, 01-138 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Pediatrics, Nutrition and Metabolic Diseases, The Children’s Memorial Health Institute, W 04-730 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] 4 NIHR Biomedical Research Center (BRC), Metabolic Unit, Great Ormond Street Hospital and Institute of Child Health, University College London, London SE1 9RT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-606-415-888 Abstract: Most plasma proteins, cell membrane proteins and other proteins are glycoproteins with sugar chains attached to the polypeptide-glycans. Glycosylation is the main element of the post- translational transformation of most human proteins. Since glycosylation processes are necessary for many different biological processes, patients present a diverse spectrum of phenotypes and severity of symptoms. The most frequently observed neurological symptoms in congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are: epilepsy, intellectual disability, myopathies, neuropathies and stroke-like episodes. Epilepsy is seen in many CDG subtypes and particularly present in the case of mutations -

Molecular Diagnostic Requisition

BAYLOR MIRACA GENETICS LABORATORIES SHIP TO: Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories 2450 Holcombe, Grand Blvd. -Receiving Dock PHONE: 800-411-GENE | FAX: 713-798-2787 | www.bmgl.com Houston, TX 77021-2024 Phone: 713-798-6555 MOLECULAR DIAGNOSTIC REQUISITION PATIENT INFORMATION SAMPLE INFORMATION NAME: DATE OF COLLECTION: / / LAST NAME FIRST NAME MI MM DD YY HOSPITAL#: ACCESSION#: DATE OF BIRTH: / / GENDER (Please select one): FEMALE MALE MM DD YY SAMPLE TYPE (Please select one): ETHNIC BACKGROUND (Select all that apply): UNKNOWN BLOOD AFRICAN AMERICAN CORD BLOOD ASIAN SKELETAL MUSCLE ASHKENAZIC JEWISH MUSCLE EUROPEAN CAUCASIAN -OR- DNA (Specify Source): HISPANIC NATIVE AMERICAN INDIAN PLACE PATIENT STICKER HERE OTHER JEWISH OTHER (Specify): OTHER (Please specify): REPORTING INFORMATION ADDITIONAL PROFESSIONAL REPORT RECIPIENTS PHYSICIAN: NAME: INSTITUTION: PHONE: FAX: PHONE: FAX: NAME: EMAIL (INTERNATIONAL CLIENT REQUIREMENT): PHONE: FAX: INDICATION FOR STUDY SYMPTOMATIC (Summarize below.): *FAMILIAL MUTATION/VARIANT ANALYSIS: COMPLETE ALL FIELDS BELOW AND ATTACH THE PROBAND'S REPORT. GENE NAME: ASYMPTOMATIC/POSITIVE FAMILY HISTORY: (ATTACH FAMILY HISTORY) MUTATION/UNCLASSIFIED VARIANT: RELATIONSHIP TO PROBAND: THIS INDIVIDUAL IS CURRENTLY: SYMPTOMATIC ASYMPTOMATIC *If family mutation is known, complete the FAMILIAL MUTATION/ VARIANT ANALYSIS section. NAME OF PROBAND: ASYMPTOMATIC/POPULATION SCREENING RELATIONSHIP TO PROBAND: OTHER (Specify clinical findings below): BMGL LAB#: A COPY OF ORIGINAL RESULTS ATTACHED IF PROBAND TESTING WAS PERFORMED AT ANOTHER LAB, CALL TO DISCUSS PRIOR TO SENDING SAMPLE. A POSITIVE CONTROL MAY BE REQUIRED IN SOME CASES. REQUIRED: NEW YORK STATE PHYSICIAN SIGNATURE OF CONSENT I certify that the patient specified above and/or their legal guardian has been informed of the benefits, risks, and limitations of the laboratory test(s) requested. -

Associated with Low Dehydrodolichol Diphosphate Synthase (DHDDS) Activity S

Sabry et al. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2016) 11:84 DOI 10.1186/s13023-016-0468-1 RESEARCH Open Access A case of fatal Type I congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG I) associated with low dehydrodolichol diphosphate synthase (DHDDS) activity S. Sabry1,2,3,4, S. Vuillaumier-Barrot1,2,5, E. Mintet1,2, M. Fasseu1,2, V. Valayannopoulos6, D. Héron7,8, N. Dorison8, C. Mignot7,8,9, N. Seta5,10, I. Chantret1,2, T. Dupré1,2,5 and S. E. H. Moore1,2* Abstract Background: Type I congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG-I) are mostly complex multisystemic diseases associated with hypoglycosylated serum glycoproteins. A subgroup harbour mutations in genes necessary for the biosynthesis of the dolichol-linked oligosaccharide (DLO) precursor that is essential for protein N-glycosylation. Here, our objective was to identify the molecular origins of disease in such a CDG-Ix patient presenting with axial hypotonia, peripheral hypertonia, enlarged liver, micropenis, cryptorchidism and sensorineural deafness associated with hypo glycosylated serum glycoproteins. Results: Targeted sequencing of DNA revealed a splice site mutation in intron 5 and a non-sense mutation in exon 4 of the dehydrodolichol diphosphate synthase gene (DHDDS). Skin biopsy fibroblasts derived from the patient revealed ~20 % residual DHDDS mRNA, ~35 % residual DHDDS activity, reduced dolichol-phosphate, truncated DLO and N-glycans, and an increased ratio of [2-3H]mannose labeled glycoprotein to [2-3H]mannose labeled DLO. Predicted truncated DHDDS transcripts did not complement rer2-deficient yeast. SiRNA-mediated down-regulation of DHDDS in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells largely mirrored the biochemical phenotype of cells from the patient. -

Viruses Like Sugars: How to Assess Glycan Involvement in Viral Attachment

microorganisms Review Viruses Like Sugars: How to Assess Glycan Involvement in Viral Attachment Gregory Mathez and Valeria Cagno * Institute of Microbiology, Lausanne University Hospital, University of Lausanne, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The first step of viral infection requires interaction with the host cell. Before finding the specific receptor that triggers entry, the majority of viruses interact with the glycocalyx. Identifying the carbohydrates that are specifically recognized by different viruses is important both for assessing the cellular tropism and for identifying new antiviral targets. Advances in the tools available for studying glycan–protein interactions have made it possible to identify them more rapidly; however, it is important to recognize the limitations of these methods in order to draw relevant conclusions. Here, we review different techniques: genetic screening, glycan arrays, enzymatic and pharmacological approaches, and surface plasmon resonance. We then detail the glycan interactions of enterovirus D68 and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), highlighting the aspects that need further clarification. Keywords: attachment receptor; viruses; glycan; sialic acid; heparan sulfate; HBGA; SARS-CoV-2; EV-D68 Citation: Mathez, G.; Cagno, V. Viruses Like Sugars: How to Assess 1. Introduction Glycan Involvement in Viral This review focuses on methods for assessing the involvement of carbohydrates in Attachment. Microorganisms 2021, 9, viral attachment and entry into the host cell. Viruses often bind to entry receptors that are 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ not abundant on the cell surface; to increase their chances of finding them, they initially microorganisms9061238 bind to attachment receptors comprising carbohydrates that are more widely expressed. -

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature Into Vascularized Glomeruli Upon Experimental Transplantation

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation † Sazia Sharmin,* Atsuhiro Taguchi,* Yusuke Kaku,* Yasuhiro Yoshimura,* Tomoko Ohmori,* ‡ † ‡ Tetsushi Sakuma, Masashi Mukoyama, Takashi Yamamoto, Hidetake Kurihara,§ and | Ryuichi Nishinakamura* *Department of Kidney Development, Institute of Molecular Embryology and Genetics, and †Department of Nephrology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan; ‡Department of Mathematical and Life Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan; §Division of Anatomy, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; and |Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Kumamoto, Japan ABSTRACT Glomerular podocytes express proteins, such as nephrin, that constitute the slit diaphragm, thereby contributing to the filtration process in the kidney. Glomerular development has been analyzed mainly in mice, whereas analysis of human kidney development has been minimal because of limited access to embryonic kidneys. We previously reported the induction of three-dimensional primordial glomeruli from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Here, using transcription activator–like effector nuclease-mediated homologous recombination, we generated human iPS cell lines that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the NPHS1 locus, which encodes nephrin, and we show that GFP expression facilitated accurate visualization of nephrin-positive podocyte formation in -

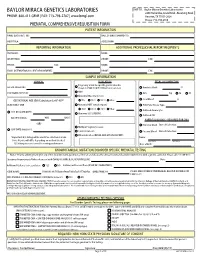

Prenatal Testing Requisition Form

BAYLOR MIRACA GENETICS LABORATORIES SHIP TO: Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories 2450 Holcombe, Grand Blvd. -Receiving Dock PHONE: 800-411-GENE | FAX: 713-798-2787 | www.bmgl.com Houston, TX 77021-2024 Phone: 713-798-6555 PRENATAL COMPREHENSIVE REQUISITION FORM PATIENT INFORMATION NAME (LAST,FIRST, MI): DATE OF BIRTH (MM/DD/YY): HOSPITAL#: ACCESSION#: REPORTING INFORMATION ADDITIONAL PROFESSIONAL REPORT RECIPIENTS PHYSICIAN: NAME: INSTITUTION: PHONE: FAX: PHONE: FAX: NAME: EMAIL (INTERNATIONAL CLIENT REQUIREMENT): PHONE: FAX: SAMPLE INFORMATION CLINICAL INDICATION FETAL SPECIMEN TYPE Pregnancy at risk for specific genetic disorder DATE OF COLLECTION: (Complete FAMILIAL MUTATION information below) Amniotic Fluid: cc AMA PERFORMING PHYSICIAN: CVS: mg TA TC Abnormal Maternal Screen: Fetal Blood: cc GESTATIONAL AGE (GA) Calculation for AF-AFP* NTD TRI 21 TRI 18 Other: SELECT ONLY ONE: Abnormal NIPT (attach report): POC/Fetal Tissue, Type: TRI 21 TRI 13 TRI 18 Other: Cultured Amniocytes U/S DATE (MM/DD/YY): Abnormal U/S (SPECIFY): Cultured CVS GA ON U/S DATE: WKS DAYS PARENTAL BLOODS - REQUIRED FOR CMA -OR- Maternal Blood Date of Collection: Multiple Pregnancy Losses LMP DATE (MM/DD/YY): Parental Concern Paternal Blood Date of Collection: Other Indication (DETAIL AND ATTACH REPORT): *Important: U/S dating will be used if no selection is made. Name: Note: Results will differ depending on method checked. Last Name First Name U/S dating increases overall screening performance. Date of Birth: KNOWN FAMILIAL MUTATION/DISORDER SPECIFIC PRENATAL TESTING Notice: Prior to ordering testing for any of the disorders listed, you must call the lab and discuss the clinical history and sample requirements with a genetic counselor. -

Myo-Glyco Disease Biology: Genetic Myopathies Caused by Abnormal Glycan Synthesis and Degradation

Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 6 (2019) 175–187 175 DOI 10.3233/JND-180369 IOS Press Review Myo-Glyco disease Biology: Genetic Myopathies Caused by Abnormal Glycan Synthesis and Degradation Motoi Kanagawa∗ Division of Molecular Brain Science, Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine, Japan Abstract. Glycosylation is a major form of post-translational modification and plays various important roles in organisms by modifying proteins or lipids, which generates functional variability and can increase their stability. Because of the physiological importance of glycosylation, defects in genes encoding proteins involved in glycosylation or glycan degradation are sometimes associated with human diseases. A number of genetic neuromuscular diseases are caused by abnormal glycan modification or degeneration. Heterogeneous and complex modification machinery, and difficulties in structural and functional analysis of glycans have impeded the understanding of how glycosylation contributes to pathology. However, recent rapid advances in glycan and genetic analyses, as well as accumulating genetic and clinical information have greatly contributed to identifying glycan structures and modification enzymes, which has led to breakthroughs in the understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of various diseases and the possible development of therapeutic strategies. For example, studies on the relationship between glycosylation and muscular dystrophy in the last two decades have significantly impacted the fields of glycobiology and neuromyology. In this review, the basis of glycan structure and biosynthesis will be briefly explained, and then molecular pathogenesis and therapeutic concepts related to neuromuscular diseases will be introduced from the point of view of the life cycle of a glycan molecule. Keywords: Glycosylation, muscular dystrophy, neuromuscular disease, therapeutic strategy STRUCTURE AND CELL BIOLOGY OF of a glycoconjugate, such as a glycoprotein and GLYCANS – AN OVERVIEW glycolipid. -

Targeted Proteomics Reveals Quantitative Differences in Low Abundance Glycosyltransferases of Patients with Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.15.291732; this version posted September 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Targeted Proteomics Reveals Quantitative Differences in Low Abundance Glycosyltransferases of Patients with Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation Roman Sakson1,2,*, Lars Beedgen3,*, Patrick Bernhard4,5,6, Keziban M. Alp7, Ni- cole Lübbehusen1, Ralph Röth8, Beate Niesler8,9, Matthias P. Mayer1, Christian Thiel3 and Thomas Ruppert1,# 1 Zentrum für Molekulare Biologie der Universität Heidelberg (ZMBH), DKFZ-ZMBH Alliance, Heidelberg, Germany 2 HBIGS, Heidelberg Biosciences International Graduate School, Heidelberg Univer- sity, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 3 Center for Child and Adolescent Medicine, Department Pediatrics I, Heidelberg Uni- versity, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 4 Institute for Surgical Pathology, Medical Center – University of Freiburg, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, Germany 5 Spemann Graduate School of Biology and Medicine (SGBM), University of Frei- burg, Germany 6 Faculty of Biology, Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany 7 Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC), 12135 Berlin, Germany 8 Department of Human Molecular Genetics, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidel- berg, Germany 9 Interdisciplinary Center for Neurosciences, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Ger- many * equal contribution # corresponding author bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.15.291732; this version posted September 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Protein glycosylation is essential in all domains of life and its mutational impairment in humans can result in severe diseases named Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation (CDGs).