The Construction Techniques and Methods for Organizing Labor Used for Bernini's Colonnade in St.Peter's, Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cladding the Mid-Century Modern: Thin Stone Veneer-Faced Precast Concrete

CLADDING THE MID-CENTURY MODERN: THIN STONE VENEER-FACED PRECAST CONCRETE Sarah Sojung Yoon Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Historic Preservation Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation Columbia University May 2016 Advisor Dr. Theodore Prudon Adjunct Professor at Columbia University Principal, Prudon & Partners Reader Sidney Freedman Director, Architectural Precast Concrete Services Precast/ Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI) Reader Kimball J. Beasley Senior Principal, Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. (WJE) ABSTRACT Cladding the Mid-Century Modern: Thin Stone Veneer-Faced Precast Concrete Sarah Sojung Yoon Dr. Theodore Prudon, Advisor With significant advancements in building technology at the turn of the twentieth century, new building materials and innovative systems changed the conventions of construction and design. New materials were introduced and old materials continued to be transformed for new uses. With growing demand after WWII forcing further modernization and standardization and greater experimentation; adequate research and testing was not always pursued. Focusing on this specific composite cladding material consisting of thin stone veneer-faced precast concrete – the official name given at the time – this research aims to identify what drove the design and how did the initial design change over time. Design decisions and changes are evident from and identified by closely studying the industry and trade literature in the form of articles, handbooks/manuals, and guide specifications. For this cladding material, there are two major industries that came together: the precast concrete industry and the stone industry. Literature from both industries provide a comprehensive understanding of their exchange and collaboration. From the information in the trade literature, case studies using early forms of thin stone veneer-faced precast concrete are identified, and the performance of the material over time is discussed. -

Decreasing Hydrothermalism at Pamukkale- Hierapolis (Anatolia) Since the 7Th Century

EGU2020-20182 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-20182 EGU General Assembly 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Decreasing hydrothermalism at Pamukkale- Hierapolis (Anatolia) since the 7th century Bassam Ghaleb1, Claude Hillaire-Marcel1, Mehmet Ozkul2, and Feride Kulali3 1Université du Québec à Montréal, GEOTOP, Montreal, Canada ([email protected]) 2Pamukkale University, Denizli, Turkey 3Uskudar University, Istanbul,Turkey The dating of travertine deposition and groundwater / hydrothermal seepages in relation to late Holocene climatic changes can be achieved using short-lived isotopes of the 238U decay series, as illustrated by the present study of the Pamukkale travertine system, at the northern edge of the Denizli and Baklan graben merging area (see Özkul et al., 2013; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2013.05.018. The strongly lithified self-built channels and modern pools where analysed for their 238U,234U,230Th, 226Ra, 210Pb and 210Po contents, whereas 238U,234U and 226Ra were measured in modern hydrothermal waters. When corrected for detrital contamination, 230Th-ages of travertine samples range from 1215±80 years, in the oldest self-built hydrothermal channels, to the Present (modern pool carbonate deposits) thus pointing to the inception of the existing huge travertine depositional systems during the very late Holocene, probably following the major Laodikeia earthquate of the early 7th century (cf. Kumsar et al., 2016; DOI 10.1007/s10064-015-0791-0). So far, the available data suggest three major growth phases of the travertine system: an early phase (7th to 8th centuries CE), an intermediate phase (~ 14th century CE) and a modern one, less than one century old. -

Michelangelo's Locations

1 3 4 He also adds the central balcony and the pope’s Michelangelo modifies the facades of Palazzo dei The project was completed by Tiberio Calcagni Cupola and Basilica di San Pietro Cappella Sistina Cappella Paolina crest, surmounted by the keys and tiara, on the Conservatori by adding a portico, and Palazzo and Giacomo Della Porta. The brothers Piazza San Pietro Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano facade. Michelangelo also plans a bridge across Senatorio with a staircase leading straight to the Guido Ascanio and Alessandro Sforza, who the Tiber that connects the Palace with villa Chigi first floor. He then builds Palazzo Nuovo giving commissioned the work, are buried in the two The long lasting works to build Saint Peter’s Basilica The chapel, dedicated to the Assumption, was Few steps from the Sistine Chapel, in the heart of (Farnesina). The work was never completed due a slightly trapezoidal shape to the square and big side niches of the chapel. Its elliptical-shaped as we know it today, started at the beginning of built on the upper floor of a fortified area of the Apostolic Palaces, is the Chapel of Saints Peter to the high costs, only a first part remains, known plans the marble basement in the middle of it, space with its sail vaults and its domes supported the XVI century, at the behest of Julius II, whose Vatican Apostolic Palace, under pope Sixtus and Paul also known as Pauline Chapel, which is as Arco dei Farnesi, along the beautiful Via Giulia. -

The Arch and Colonnade of the Manhattan Bridge Approach and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 25, 1975, Number 3 LP-0899 THE ARCH AND COLONNAD E OF THE MANHATTAN BRIDGE APPROACH, Manhattan Bridge Plaza at Canal Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1912-15; architects Carr~re & Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough o£Manhattan Tax Map Block 290, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the described improvement is situated. On September 23, 1975, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Arch and Colonnade of the Manhattan Bridge Approach and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No . 3). The hearing had been duly ad vertised in accordance with . the provisions of law. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Manhattan Bridge Approach, a monumental gateway to the bridge, occupies a gently sloping elliptical plaza bounded by Canal, Forsyth and Bayard Streets and the Bowery. Originally designed to accommodate the flow of traffic, it employed traditional forms of arch and colonnade in a monument al Beaux-Arts style gateway. The triumphal arch was modeled after the 17th-century Porte St. Denis in Paris and the colonnade was inspired by Bernini's monumental colonnade enframing St. Peter's Square in Rome. Carr~re &Hastings, whose designs for monumental civic architecture include the New York Public Library and Grand Army Plaza, in Manhattan, were the architects of the approaches to the Manhattan Bridge and designed both its Brooklyn and Manhattan approaches. The design of the Manhattan Bridge , the the third bridge to cross the East River, aroused a good deal of controversy. -

Springs of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIBECTOB WATER- SUPPLY PAPER 338 SPRINGS OF CALIFORNIA BY GEKALD A. WARING WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1915 CONTENTS. Page. lntroduction by W. C. Mendenhall ... .. ................................... 5 Physical features of California ...... ....... .. .. ... .. ....... .............. 7 Natural divisions ................... ... .. ........................... 7 Coast Ranges ..................................... ....•.......... _._._ 7 11 ~~:~~::!:: :~~e:_-_-_·.-.·.·: ~::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ::::: ::: 12 Sierra Nevada .................... .................................... 12 Southeastern desert ......................... ............. .. ..... ... 13 Faults ..... ....... ... ................ ·.. : ..... ................ ..... 14 Natural waters ................................ _.......................... 15 Use of terms "mineral water" and ''pure water" ............... : .·...... 15 ,,uneral analysis of water ................................ .. ... ........ 15 Source and amount of substances in water ................. ............. 17 Degree of concentration of natural waters ........................ ..· .... 21 Properties of mineral waters . ................... ...... _. _.. .. _... _....• 22 Temperature of natural waters ... : ....................... _.. _..... .... : . 24 Classification of mineral waters ............ .......... .. .. _. .. _......... _ 25 Therapeutic value of waters .................................... ... ... 26 Analyses -

TRAVERTINE-MARL DEPOSITS of the VALLEY and RIDGE PROVINCE of VIRGINIA - a PRELIMINARY REPORT David A

- Vol. 31 February 1985 No. 1 TRAVERTINE-MARL DEPOSITS OF THE VALLEY AND RIDGE PROVINCE OF VIRGINIA - A PRELIMINARY REPORT David A. Hubbard, Jr.1, William F. Gianninil and Michelle M. Lorah2 The travertine and marl deposits of Virginia's Valley and Ridge province are the result of precipitation of calcium carbonate from fresh water streams and springs. Travertine is white to light yellowish brown and has a massive or concretionary structure. Buildups of this material tend to form cascades or waterfalls along streams (Figure 1). Marl refers to white to dark yellowish brown, loose, earthy deposits of calcium carbonate (Figure 2). Deposits of these carbonate materials are related and have formed during the Quaternary period. This preliminary report is a compilation of some litei-ature and observations of these materials. A depositional model is proposed. These deposits have long been visited by man. Projectile points, pottery fragments, and firepits record the visitation of American Indians to Frederick and Augusta county sites. Thomas Jefferson (1825) wrote an account of the Falling Spring Falls from a visit prior to 1781. Aesthetic and economic considerations eontinue to attract interest in these deposits. 'Virginia Division of Mineral Resources, Charlot- Figure 1. Travertine waterfall and cascade series tesville, VA on Falling Springs Creek, Alleghany County, 2Department of Environmental Sciences, Univer- Virginia. Note man standing in center of left sity of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA margin. 2 VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Vol. 31 Figure 2. An extensive marl deposit located in Figure 3. Rimstone dam form resulting from Frederick County, Virginia. Stream, in fore- precipitation of calcium carbonate in Mill Creek, ground, has incised and drained the deposit. -

Federal Building United States Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio, Was Designed and Constructed Under the U

FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE Youngstown, Ohio Youngstown, Ohio The Federal Building United States Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio, was designed and constructed under the U.S. General Services Administration’s Design Excellence Program, an initiative to create and preserve a legacy of outstanding public buildings that will be used and enjoyed now and by future generations of Americans. Special thanks to the Honorable William T. Bodoh, Chief Bankruptcy Judge, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, for his commitment and dedication to a building of outstanding quality that is a tribute to the role of the judiciary in our democratic society and worthy U.S. General Services Administration U.S. General Services Administration of the American people. Public Buildings Service Office of the Chief Architect Center for Design Excellence and the Arts October 2002 1800 F Street, NW Washington, DC 20405 2025011888 FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE Youngstown, Ohio Youngstown, Ohio The Federal Building United States Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio, was designed and constructed under the U.S. General Services Administration’s Design Excellence Program, an initiative to create and preserve a legacy of outstanding public buildings that will be used and enjoyed now and by future generations of Americans. Special thanks to the Honorable William T. Bodoh, Chief Bankruptcy Judge, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, for his commitment and dedication to a building of outstanding quality that is a tribute to the role of the judiciary in our democratic society and worthy U.S. -

COLONNADE RENOVATION Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia

CSI Richmond – April Project Spotlight - Glavé & Holmes Architecture COLONNADE RENOVATION Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia Washington and Lee University’s front campus was designated a National Historic District in 1973, described by the Interior as “one of the most dignified and beautiful college campuses in the nation”. In the center stands the Colonnade, comprised of the five most iconic buildings in the historic district: Washington, Payne, Robinson, Newcomb, and Tucker Halls. The phased rehabilitation of the building spanned eight years. The Colonnade is deeply revered, making any change sensitive. However, restoring its vitality was paramount to the University: code deficiencies, inefficient infrastructure, and worn interiors reflected decades of use. Offices were inadequate, spaces for interaction were sparse, technology was an afterthought, and there weren’t even bathrooms on the third floors. Understanding the beloved nature of the buildings, the University established lofty goals for this undertaking. G&HA followed the guidelines from the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation to preserve the major character and defining features in each building while upgrading all the MEP and life safety systems throughout. Because of space constraints, a new utility structure was designed and located across Stemmons Plaza to sit below grade. The structure’s green roof and seating areas integrate it into the site and enhance the landscape. The project achieved LEED Silver and historic tax credits. — COLONNADE -

Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: Rinascita

Niccolo’ Machiavelli (1469‐1527) • Political career (1498‐1512) • Official in Florentine Republic – Diplomat: observes Cesare Borgia – Organizes Florentine militia and military campaign against Pisa – Deposed when Medici return in 1512 – Suspected of treason he is tortured; retired to his estate Major Works: The Prince (1513): advice to Prince, how to obtain and maintain power Discourses on Livy (1517): Admiration of Roman republic and comparisons with his own time – Ability to channel civil strife into effective government – Admiration of religion of the Romans and its political consequences – Criticism of Papacy in Italy – Revisionism of Augustinian Christian paradigm Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: rinascita • Early Renaissance: 1420‐1500c • ‐‐1420: return of papacy (Martin V) to Rome from Avignon • High Renaissance: 1500‐1520/1527 • ‐‐ 1503: Ascension of Julius II as Pope; arrival of Bramante, Raphael and Michelangelo; 1513: Leo X • ‐‐1520: Death of Raphael; 1527 Sack of Rome • Late Renaissance (Mannerism): 1520/27‐1600 • ‐‐1563: Last session of Council of Trent on sacred images Artistic Renaissance in Rome • Patronage of popes and cardinals of humanists and artists from Florence and central/northern Italy • Focus in painting shifts from a theocentric symbolism to a humanistic realism • The recuperation of classical forms (going “ad fontes”) ‐‐Study of classical architecture and statuary; recovery of texts Vitruvius’ De architectura (1414—Poggio Bracciolini) • The application of mathematics to art/architecture and the elaboration of single point perspective –Filippo Brunellschi 1414 (develops rules of mathematical perspective) –L. B. Alberti‐‐ Della pittura (1432); De re aedificatoria (1452) • Changing status of the artist from an artisan (mechanical arts) to intellectual (liberal arts; math and theory); sense of individual genius –Paragon of the arts: painting vs. -

Late Renaissance 1520S

ARCG221- HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE II Late Renaissance and Mannerism 1520s - 1580s Dr. Abdurrahman Mohamed Saint Peters cathedral in the late renaissance Giuliano de Sangallo, Giocondo and Raphael were followed by Baldasari Belotti then by de Sangallo the younger and both died by 1546. All of these architects inserted changes on the original design of Bramante. Michael Angelo was commissioned in 1546 and most of the existing design of the cathedral belongs to him. Da Snagalo the younger design for Saint Peter’s church Michelangelo plan for Saint Peter’s church Ricci, Corrado.High and late Renaissance Architecture in Italy. pXII Michelangelo dome of St Peter’s Cathedral Roof of St. Peter's Basilica with a coffee bar and a gift shop. http://www.saintpetersbasilica.org/Exterior/SP-Square-Area.htm The grand east facade of St Peter's Basilica, 116 m wide and 53 m high. Built from 1608 to 1614, it was designed by Carlo Maderna. The central balcony is called the Loggia of the Blessings and is used for the announcement of the new pope with his blessing. St. Peter’s Cathedral View from St. Peter’s square designed by Bernini http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Vatican_StPeter_Square.jpg Palazzo Farnese, De Sangallo the Younger, 1534, upper floor by Michelangelo Ground floor plan 1- Courtyard 2- Entrance hall 3- Entrance fro the square Palazzo Farnese, De Sangallo the Younger, 1534, upper floor by Michelangelo Main façade Villa Giulia Palazzo Villa Giulia http://www.flickr.com/photos/dealvariis/4155570306/in/set-72157622925876488 Quoins Mannerism 1550-1600 The architecture of late renaissance which started at the end of 3rd decade of the 16th century followed the classical origins of the early and high renaissance. -

The University of Western Ontario Uses a Plagiarism-Checking Site Called Turnitin.Com

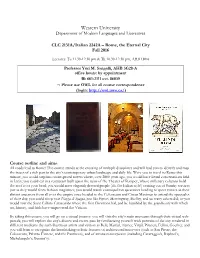

Western University Department of Modern Languages and Literatures CLC 2131A/Italian 2242A – Rome, the Eternal City Fall 2016 Lectures: Tu 11.30-12.30 pm & Th 10.30-12.30 pm, AHB 1B04 Professor Yuri M. Sangalli, AHB 3G28-A office hours: by appointment ☎: 661-2111 ext. 86039 ✉: Please use OWL for all course correspondence (login: http://owl.uwo.ca/) Course outline and aims: All roads lead to Rome! This course stands at the crossing of multiple disciplines and will lead you to identify and map the traces of a rich past in the city’s contemporary urban landscape and daily life. Were you to travel to Rome this minute, you would step into stone-paved streets where, over 2000 years ago, you would have heard conversations held in Latin; you could eat in a restaurant built upon the ruins of the Theater of Pompey, whose millenary columns hold the roof over your head; you would meet elegantly dressed people (ah, the Italian style!) coming out of Sunday services just as they would from fashion magazines; you would watch cosmopolitan spectators heading to sport venues as their distant ancestors from all over the empire once headed to the Colosseum and Circus Maximus to attend the spectacles of their day; you could sleep near Piazza di Spagna, just like Byron, Hemingway, Shelley, and so many others did; or you would visit the Saint Callisto Catacombs where the first Christians hid, and be humbled by the grandiosity with which art, history, and faith have empowered the Vatican. By taking this course, you will go on a virtual journey: you will visit -

• Exceptional Level of Private Access to Spectacular

Exceptional level of private access to spectacular churches, palaces & collections Rare opportunity to visit the Sistine Chapel, privately, at night & with no others present Explore the unprecedented riches of Villa Borghese with its six Caravaggio paintings & the finest collection of Bernini’s sculptures Our group will be received as guests in several magnificent private palaces & villas Visit based in the very comfortable 3* Superior Albergo del Senato located just by the Pantheon Annibale Caracci, Two putti spy on a pair of Heavenly Lovers, Palazzo Farnese, Rome If all roads lead to Rome, not all organised visits open the doors of Rome’s many private palaces and villas! This visit is an exception as it is almost entirely devoted to a series of specially arranged private visits. We shall enjoy extraordinary levels of access to some of the most important palaces, villas and collections in Rome. How is this possible? Over the years CICERONI Travel has built up an unrivalled series of introductions and contacts in Roman society, both sacred and secular. This allows us to organise what we believe to be the finest tour of its kind available. It is an opportunity which you are cordially invited to participate in as our guests. The overriding theme of the visit will be to allow you to enjoy a level of access to remarkable buildings and their collections, whilst recreating the perspective of an earlier, more privileged world. These visits will chart the transformation of Rome during the Renaissance and Baroque periods as a succession of remarkable Popes, Cardinals and Princes vied to outdo each other.