Memorializing Sex Workers in Vancouver's West End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UBCM Community Excellence Awards Application Now Available

REGIONAL COUNCIL INFORMATION PACKAGE June 28, 2007 Page Calendars 5 Regional Council Calendar NRRD/Town Departments 6 REC. SERVICES Poster Re: Canada Day in the Park 7 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT & PLANNING SERVICES Notice Re: Tourism Strategic Plan Public Consultation Meeting, NLC, July 10th UBCM 8-9 Notice Re: Inviting Applications for the 2007 Energy Aware Award 10-18 Notice Re: 2007 UBCM Community Excellence Awards Application Now Available 19-20 TOWN OF VIEW ROYAL Submission to Advisory Panel Re: Railway Safety Act Review Page 1 of 66 Page Provincial Ministries 21-22 OFFICE OF THE PREMIER Letter Re: Cabinet Minister Request Form for 102nd UBCM Annual Convention 23 MINISTRY OF HEALTH Letter Re: Tobacco Control Regulatory Discussion Paper Federal Ministries 24 Hon. JAY HILL, P.C., M.P. Notice Re: Call for Applications for Funding Program 'New Horizons for Seniors' Miscellaneous Correspondence 25-29 DONALD E. TAYLOR Letter to Prime Minister Re: Alaska-Canada Utility Corridor 30-34 DONALD E. TAYLOR Letter to Mayor Colin Kinsley Re: Alaska - Canada Utility Corridor 35 DONALD E. TAYLOR Letter to Prime Minister Re: Additional Information 36 DAVID SUZUKI FOUNDATION Letter Re: Copy of Zoned RS-1 (Residential Salmon-1) 37-39 W. ZARCHIKOFF & ASSOCIATES Notice & Registration Re: 4th Regional Forum: Crystal Meth & New Drug Trends, Vancouver, Sept. 13-14th Page 2 of 66 Page Miscellaneous Correspondence 40-43 OFFICIAL OPPOSITION Letter Re: Affects of TILMA on Local Government 44-49 BEN BENNETT COMMUNICATIONS PPS REVIEW - MANAGING WASTE RESPONSIBLY Trade Organizations 50-53 HELLO NORTH Notice Re: Stay Another Day Program - Northeastern BC Events - June 28 - July 4 54-55 TOURISM RESEARCH INNOVATION PROJECT Notice Re: Objectives & Activities 56-59 BC FOREST SAFETY COUNCIL TruckSafe Rumblings Business & Industry 60-62 TERASEN GAS Invitation Re: Terasen Reception at the 2007 UBCM Annual Convention, Sept. -

Ujjal Dosanjh: B.C.'S Indian-Born Premier

Contents Ujjal Dosanjh: B.C.'s Indian-Born Premier In an attempt to hang onto power and to stage a comeback in the court of public opinion after the resignation of Glen Clark, the beleaguered NDP government of British Columbia picks Ujjal Dosanjh as party leader and premier. The former attorney general of the province was selected following a process that itself was not without controversy. As a Canadian pioneer, Dosanjh becomes the first Indian-born head of government in Canada. A role model as well, the new premier has traveled far to a nation that early in the 1900s restricted Indian immigration by an order-in-council. Ironically, Dosanjh, no stranger to controversy and personal struggle, is the grandson of a revolutionary who was jailed by the British during India s fight for independence. Introduction The Ethnic Question A Troublesome Inheritance An Experiential Education The Visible Majority Multiculturalism in Canada Racial History in Canada Discussion, Research, and Essay Questions Comprehensive News in Review Study Modules Using both the print and non-print material from various issues of News in Review, teachers and students can create comprehensive, thematic modules that are excellent for research purposes, independent assignments, and small group study. We recommend the stories indicated below for the universal issues they represent and for the archival and historic material they contain. Vander Zalm: A Question of Accountability, May 1991 Glen Clark: Mandate Squandered? October 1999 Other Related Videos Available from CBC Learning Does Your Resource Collection Include These CBC Videos? Skin Deep: The Science of Race Who Is A Real Canadian? Introduction Ujjal Dosanjh: B.C.'s Indian-Born Premier On February 19, 2000, political history was made in British Columbia when the New Democratic Party chose Ujjal Dosanjh to be its new leader, and as a result, for the first time in Canada, an Indo-Canadian became head of government in a provincial legislature. -

Directors'notice of New Business

R-2 DIRECTORS’ NOTICE OF NEW BUSINESS To: Chair and Directors Date: January 16, 2019 From: Director Goodings, Electoral Area ‘B’ Subject: Composite Political Newsletter PURPOSE / ISSUE: In the January 11, 2019 edition of the Directors’ Information package there was a complimentary issue of a political newsletter entitled “The Composite Advisor.” The monthly newsletter provides comprehensive news and strategic analysis regarding BC Politics and Policy. RECOMMENDATION / ACTION: [All Directors – Corporate Weighted] That the Regional District purchase an annual subscription (10 issues) of the Composite Public Affairs newsletter for an amount of $87 including GST. BACKGROUND/RATIONALE: I feel the newsletter is worthwhile for the Board’s reference. ATTACHMENTS: January 4, 2019 issue Dept. Head: CAO: Page 1 of 1 January 31, 2019 R-2 Composite Public Affairs Inc. January 4, 2019 Karen Goodings Peace River Regional District Box 810 Dawson Creek, BC V1G 4H8 Dear Karen, It is my pleasure to provide you with a complimentary issue of our new political newsletter, The Composite Advisor. British Columbia today is in the midst of an exciting political drama — one that may last for the next many months, or (as I believe) the next several years. At present, a New Democratic Party government led by Premier John Horgan and supported by Andrew Weaver's Green Party, holds a narrow advantage in the Legislative Assembly. And after 16 years in power, the long-governing BC Liberals now sit on the opposition benches with a relatively-new leader in Andrew Wilkinson. B.C.'s next general-election is scheduled for October 2021, almost three years from now, but as the old saying goes: 'The only thing certain, is uncertainty." (The best political quote in this regard may have been by British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan who, asked by a reporter what might transpire to change his government's course of action, replied: "Events, dear boy, events." New research suggests that MacMillan never said it — but it's still a great quote!) Composite Public Affairs Inc. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents BRITISH COLUMBIA: THE CUTS BEGIN Introduction The Campbell Plan Idiosyncratic Politics Discussion, Research, and Essay Questions BRITISH COLUMBIA: THE CUTS BEGIN Introduction On February 13, 2002, British Columbia pay for a measure they viewed as short- Premier Gordon Campbell delivered a sighted and ill-timed. Others were outraged televised address to the province, shortly that he had ordered the province’s striking after introducing his Liberal government’s teachers back to work, and that he had first budget. Clad in a sombre black business threatened to impose a salary settlement on suit, Campbell did not have much good news them that most viewed as unsatisfactory. to report to B.C. residents, the vast majority Labour groups were incensed at his decision of whom had given his party a huge majority to reopen signed contracts affecting health- in the May 2001 election. He apologized for care workers and others in the public sector, the difficult and quite likely unpopular steps in order to roll back their wages and benefits. his government believed it was necessary to Community groups servicing the needs of the take in the months to come. He claimed they homeless and other marginalized people in were necessary in order to wrestle down the Vancouver and elsewhere looked in vain for $4.4-billion deficit that he asserted had been any indication from the government that inherited by his government from its NDP funding for their activities would be in- predecessor. Acknowledging that cuts to creased. Environmentalists were deeply education, health care, and social programs, troubled by what they regarded as along with a significant reduction in the Campbell’s lack of sympathy with their public sector and a reopening of contracts concerns for preserving the province’s with civil servants would arouse resentment forests. -

1 Sustainable Urban Development in Canada: Global Urban

Sustainable Urban Development in Canada: Global Urban Development (GUD) Report to the Government of Sweden’s Mistra Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research Dr. Nola-Kate Seymoar, President and CEO, International Centre for Sustainable Cities, Vancouver, Canada, September 20071 Part I: Background and Major Developments 1. The Canadian Urban Agenda In 1999 the National Roundtable on Environment and Economy (NRTEE)’s International Committee, chaired by Mike Harcourt (former Mayor of Vancouver and Premier of British Columbia), called for a program that would market Canadian know how and technology about urban sustainability – in cities in developing and newly industrializing countries. In response, the Sustainable Cities Initiative (SCI) was created in Industry Canada, and began piloting its programs in 1999 in China, Brazil and Poland. It worked in partnership with local municipalities and a number of private sector and not-for-profit partners including the International Centre for Sustainable Cities (ICSC). Needs assessments (roadmaps) were completed for each city and based on these roadmaps, Canadian suppliers were engaged to respond – in some cases on a straight commercial basis paid by the local authority and in others on the basis of assistance from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and other aid agencies. By 2002, the program had won an award from the World Business Council for Sustainable Development and was expanded overseas to 17 cities. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) had been operating an international program since the late eighties2 and with financial support from CIDA, FCM, the Canadian Urban Institute (CUI) and a private sector consulting firm (AgriTeam) developed a number of ‘local government support programs’ in Central Europe and South East Asia. -

Transitions Fiscal and Political Federalism in an Era of Change

Canada: The State of the Federation 2006/07 Transitions Fiscal and Political Federalism in an Era of Change Edited by John R. Allan Thomas J. Courchene Christian Leuprecht Conference organizers: Sean Conway Peter M. Leslie Christian Leuprecht Institute of Intergovernmental Relations School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University McGill-Queen’s University Press Montreal & Kingston • London • Ithaca SOTF2006/07Prelims 1 9/17/08, 2:32 PM The Institute of Intergovernmental Relations The Institute is the only academic organization in Canada whose mandate is solely to promote research and communication on the challenges facing the federal system. Current research interests include fiscal federalism, health policy, the reform of federal po- litical institutions and the machinery of federal-provincial relations, Canadian federalism and the global economy, and comparative federalism. The Institute pursues these objectives through research conducted by its own staff and other scholars, through its publication program, and through seminars and conferences. The Institute links academics and practitioners of federalism in federal and provincial govern- ments and the private sector. The Institute of Intergovernmental Relations receives ongoing financial support from the J.A. Corry Memorial Endowment Fund, the Royal Bank of Canada Endowment Fund, the Government of Canada, and the governments of Manitoba and Ontario. We are grateful for this support, which enables the Institute to sustain its extensive program of research, publication, and related activities. L’Institut des relations intergouvernementales L’Institut est le seul organisme universitaire canadien à se consacrer exclusivement à la recherche et aux échanges sur les questions du fédéralisme. Les priorités de recherche de l’Institut portent présentement sur le fédéralisme fiscal, la santé, la modification éventuelle des institutions politiques fédérales, les mécanismes de relations fédérales-provinciales, le fédéralisme canadien au regard de l’économie mondiale et le fédéralisme comparatif. -

Greenest City” Agenda

The Urban Politics of Vancouver’s “Greenest City” Agenda by Michael Barrett Soron B.A. (Political Science), University of Calgary 2007 Research Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Urban Studies in the Urban Studies Program Faculty of Arts of Social Sciences © Michael Barrett Soron 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Michael Barrett Soron Degree: Master of Urban Studies Title of Thesis: The Urban Politics of Vancouver’s “Greenest City” Agenda Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Peter V. Hall Dr. Karen Ferguson Senior Supervisor Associate Professor, Urban Studies and History Simon Fraser University Dr. Anthony Perl Supervisor Director, Urban Studies Professor, Urban Studies and Political Science Simon Fraser University Dr. Eugene McCann Internal Examiner Associate Professor, Geography Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: January 13, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii STATEMENT OF ETHICS APPROVAL The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: (a) Human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or (b) Advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research (c) as a co-investigator, collaborator or research assistant in a research project approved in advance, or (d) as a member of a course approved in advance for minimal risk human research, by the Office of Research Ethics. -

Contributors

Contributors Michael Boudreau is Professor in the Department of Criminology & Criminal Justice at St. Thomas University. He is the author of City of Order: Crime & Society in Halifax, 1918-1935 (UBC Press, 2012) which was short-listed in 2013 for the Canadian Historical Association’s annual prize for the book “judged to have made the most significant contribution to the understanding of the Canadian past.” He has recently written a blog posting entitled “The Legalization of Cannabis in New Brunswick” (https://acadiensis.wordpress.com/2017/10/11/the-legalization-of- cannabis-in-new-brunswick/) and he is researching capital punishment and executions in New Brunswick, 1869-1957. Wade Davis is Professor of Anthropology and the BC Leadership Chair in Cultures and Ecosystems at Risk at the University of British Columbia. Between 1999 and 2013 he served as Explorer-in-Residence at the National Geographic Society. Author of twenty books, including One River, The Wayfinders and Into the Silence, winner of the 2012 Samuel Johnson prize, he is the recipient of eleven honorary degrees, as well as the 2009 Gold Medal from the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, the 2011 Explorers Medal, the 2012 David Fairchild Medal for botanical exploration, and the 2015 Centennial Medal of Harvard University. In 2016 he was made a Member of the Order of Canada. Jamie Lee Hamilton is a trans, Metis, sex work, and anti-poverty activist with deep roots in the Downtown Eastside. Jamie Lee has run numerous times as a political independent for municipal council and Park Board, and she has operated her social club, Forbidden City, for ten years. -

The Work of the Lgbtq Civic Advisory Committee, 2009-14

Queering Vancouver: The Work of the lgbtq Civic Advisory Committee, 2009-14 Catherine Murray* he proposition, so often asserted, that Vancouver is an avant- garde paradise for people who identify as lgbtq (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, and queer) merits careful examination.1 What evidence is usually cited? Social movement historians confirm that T lgbtq the city was the site of the first organization – the Association for Social Knowledge (ask) – that influenced national and regional social movements; that it developed a “thick,” active, and diverse associative structure of local gay, lesbian, and transgender rights and service groups; that it was the site of transformative protests or events; and that it is today well ensconced within Pacific Northwest and global social networks.2 Its lgbtq groups have achieved a distinctive record of groundbreaking struggles – even if there is as yet little agreement among social historians * I am indebted to the International Women’s World (2011) panel, the members of which discussed the first draft of this article; to Sarah Sparks, research assistant and MA graduate in Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies at Simon Fraser University; the constructive anonymous reviewers from BC Studies; and, especially, BC Studies’ editor Graeme Wynn. 1 Manon Tremblay, ed., Queer Mobilizations: Social Movement Activism and Canadian Public Policy (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2015), 31. Like Tremblay, I use the term “queer” to designate all non-heterosexual people. 2 For queer urban history of Vancouver, see Anne-Marie Bouthillette, “Queer and Gendered Housing: A Tale of Two Neighborhoods in Vancouver,” in Queers in Space: Communities, Public Spaces, Sites of Resistance, ed. -

Supporting Survivors Across the Years

EVA BC Annual Training Forum Supporting Survivors Across the Years November 28 and 29, 2019 Sheraton Vancouver Airport Hotel Richmond, BC MEET EVA BC Welcome and Acknowledgements Welcome to the 2019 Annual Training Forum, Supporting Survivors Across the Special thanks to the EVA BC Years, organized by the Ending Violence Board Members and Staff on the Training Forum Planning Association of BC (EVA BC). Committee who planned and coordinated this Forum. We are thrilled to have the opportunity to bring together those involved in STV Counselling, STV Outreach, Much gratitude and appreciation Multicultural Outreach, Community-Based Victim Services to all of the workshop facilitators programs, Sexual Assault/Woman Assault Centres, and keynote speakers for the and those involved in gender-based violence response time and energy they have and coordination committees from across BC, to learn given us. Many thanks to you! together and from one another about the wide range of issues that affect those who experience gender-based EVA BC would like to violence and abuse at any time of life, from childhood respectfully acknowledge that onward to adulthood and advanced age. our Annual Training Forum takes place on unceded, We want to extend our profound appreciation in ancestral, and traditional acknowledging the following partners and sponsors for territories of the sc̓ əwaθenaɁɬ their donations and support: təməxʷ (Tsawwassen), S’ólh Téméxw (Stó:lō), Kwantlen, BC Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General Stz’uminus, and xʷməθkʷəy̓ əm Odin Books (Musqueam) peoples. Sheraton Vancouver Airport Hotel Scotiabank Colour Time Printing & Digital Imaging Uber Span Communications Artwork “Pilgrim’s Journey” kindly provided by Vancouver artist Joey Mallett. -

Stigma Cities: Dystopian Urban Identities in the United States West and South in the Twentieth Century

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 8-2009 Stigma Cities: Dystopian Urban Identities In The United States West And South In The Twentieth Century Jonathan Lavon Foster University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Immune System Diseases Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Social History Commons, United States History Commons, and the Virus Diseases Commons Repository Citation Foster, Jonathan Lavon, "Stigma Cities: Dystopian Urban Identities In The United States West And South In The Twentieth Century" (2009). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1206. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/2797195 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STIGMA CITIES: DYSTOPIAN URBAN IDENTITIES IN THE UNITED STATES WEST AND SOUTH IN THE -

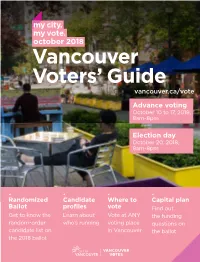

2018 Voters Guide Large Print | English

Vancouver Voters’ Guide vancouver.ca/vote Advance voting October 10 to 17, 2018, 8am-8pm Election day October 20, 2018, 8am-8pm Randomized Candidate Where to Capital plan Ballot profiles vote Find out Get to know the Learn about Vote at ANY the funding random-order who’s running voting place questions on candidate list on in Vancouver the ballot the 2018 ballot New for you in 2018 Names listed in random order An audio version is on the ballot available at vancouver. Candidates are listed in random ca/vote, reading all order, NOT alphabetical order on voter information except the ballot this year. Get ready: candidate statements. Plan your vote with the online Ì Kids can vote! tool at vancouver.ca/plan- On October 13 and 14, your-vote, or the worksheet in kids can vote in the this guide. City’s special program to Get to know the random encourage kids to vote order list at vancouver.ca/ in the future. See “Kids vote or on the worksheet in Vote” in the table of this guide. contents. Leave time to vote: consider Vote at shelters, drop-in voting in advance from centres and small care October 10 to 17, as wait times facilities may be shorter. We’re expanding mobile Voter information cards are voting to increase voting bundled by last name. access for those with socioeconomic or other Everyone at the same address barriers. with the same last name will get their cards in one Ì Selfie backdrops envelope. will be at all voting locations! Translated, large print, and audio versions of the voters’ Share a selfie to guide are available.