Evaluation of the Prisoner Re-Entry Initiative Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

RFR Template

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE DIVISION OF CAPITAL ASSET MANAGEMENT AND MAINTENANCE ONE ASHBURTON PLACE 15TH FLOOR BOSTON, MA 02108 Request for Response (RFR) Commonwealth of Massachusetts Energy Intelligence System COMMBUYS Bid#: Agency Document Number: DCP2127E AD1 UNSPC Code: 2.12.2021 Please Note: This is a single document associated with a complete Bid (also referred to as Solicitation) that can be found on COMMBUYS (www.COMMBUYS.com). All Bidders are responsible for reviewing and adhering to all information, forms and requirements for the entire Bid, which are all incorporated into the Bid. Bidders may also contact the COMMBUYS Helpdesk at [email protected] or the COMMBUYS Helpline at 1-888-MA-STATE. The Helpline is staffed from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM Monday through Friday Eastern Standard or Daylight time, as applicable, except on federal, state and Suffolk county holidays. Document Sensitivity Level: High during development; Low once published. Revised: December 23, 2014 1 RFR INTRODUCTION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION ....................................................... 1 1.1 Procurement Scope and Description ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background Information ........................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Applicable Procurement Law ................................................................................................. 2 1.4 Number of Awards ................................................................................................................. -

Corporate Plan Summary, “We”, “Us”, “Our” and “The Corporation” Mean CBC/Radio-Canada

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 2 2 . OUR COMMITMENT TO TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY 3 3. WHO WE ARE AND OUR SERVICES 4 4. OUR OPERATING ENVIRONMENT 6 5. Y OUR STORIES, TAKEN TO HEAR T – STRATEGIC INITIATIVES 2019-2022 8 6. MEASURING OUR PERFORMANCE 15 7. FINANCIAL OUTLOOK 22 APPENDIX A: FINANCIAL PROJECTIONS 24 APPENDIX B: CAPITAL BUDGET 25 APPENDIX C: RISK MANAGEMENT 28 APPENDIX D: OUR MANDATE AND GOVERNANCE 34 EDITORIAL NOTE In the Corporate Plan Summary, “we”, “us”, “our” and “the Corporation” mean CBC/Radio-Canada. NOTE REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS The Corporate Plan Summary contains forward-looking statements regarding objectives, strategic initiatives, and expected financial and operational results. Forward-looking statements are typically identified by words such as “may,” “should,” “could,” “would” and “will,” as well as expressions such as “believe,” “expect,” “forecast,” “anticipate,” “intend,” “plan,” “estimate” and other similar expressions. Forward-looking statements are based on the following broad assumptions: CBC/Radio-Canada’s government funding remains consistent with amounts announced in the federal budget, and the broadcasting regulatory environment will not change significantly. Key risks and uncertainties are described in the Risk Management section in Appendix C. However, some risks and uncertainties are by definition difficult to predict and are beyond our control. They include, but are not limited to, economic, financial, advertising market, technical and regulatory conditions. These and other factors may cause actual results to differ substantially from the expectations stated or implied in forward-looking statements. NOTE REGARDING PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT We rely on data from both internal tools and third parties to measure our performance metrics. -

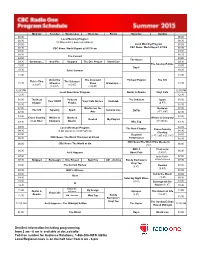

CBC Radio One - Program Schedule Summer 2020

CBC Radio One - Program Schedule Summer 2020 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 6:00 AM 6:00 AM 6:30 Local Morning Program 6:30 (5:30 AM start in selected markets) Local Morning Program 7:00 CBC News: World Report 7:00 7:30 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 AM at 6/7/8/9 AM 8:00 8:00 8:30 8:30 9:00 The Current The 9:00 9:30 House The Sunday 9:30 10:00 Edition 10:00 Day 6 10:30 q What On Earth 10:30 More with 11:00 Cost Of Living Anna Maria 11:00 CBC Podcast Inappropriate Under The Tremonti Questions Cost Of Under The 11:30 Showcase First Day Back Influence 11:30 (3:30 NT) Living (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) Influence 12:00 PM Vinyl 12:00 PM Local Noon Hour Program Quirks & Quarks 12:30 Cafe 12:30 1:00 The Next More with The Doc Project White Coat 1:00 Unreserved Tapestry Ana Maria Spark 1:30 Chapter Tremonti Laugh Out Loud The Debaters (4 PT) 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Podcast Now or Canada Podcast Tapestry 2:00 Spark Playlist 2:30 Afternoon Playlist Never Live (3 PT, 4 MT) 2:30 Writers & 3:00 Writers & Quirks & Story From Marvin’s Now 3:00 Reclaimed or Company 3:30 Company Quarks Here Room Never (5 CT/MT/ PT) 3:30 4:00 The Next Cross 4:00 Local Afternoon Program Chapter Country 4:30 (3 PM start in selected markets) Checkup 4:30 (1 PT, 2 MT, 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 PM Regional 3 CT, 5 AT) 5:00 5:30 Performance 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News: The World This Weekend (7 AT) 6:00 Laugh Out Loud White Coat, Black Art 6:30 (7:30 AT) (7:30 AT) 6:30 As It Happens 7:00 Unreserved 7:00 (8 -

Agenda and Meeting Docket

Board and Board Committee Meetings Monday January 28 and Tuesday January 29, 2019 Open Session Tuesday January 29, 2019 11:00 am –12:00 pm Senate and Board Chambers, University Centre DRAFT AGENDA 1. Approval of Agenda MOTION: THAT the agenda of the open session of the regular meeting of January 29, 2019 be approved. 2. Approval of Summary Record of the Meeting of November 27, 2018 (attached) MOTION: THAT the summary record of the open session of the regular meeting of November 27, 2018 be approved. 3. Business Arising from the Summary Record 4. Chair’s Remarks 5. Correspondence 6. President’s Report a. Update on Off Campus Activity Risk Management Policy 7. External Relations Update BOG-Jan29/19-33 CONSENT 8. Operations and Facilities Committee (Ms. Daphne Corbett) a. Status Report on Capital Projects BOG-Jan29/19-19A b. New and Revised Awards BOG-Jan29/19-03 MOTION: That the Board of Governors approve the new and revised undergraduate and graduate awards set out in the attached document and listed below: • Schulich Leader Scholarship (revised) • STÓ:LŌ Legacy Scholarship (revised) • Canadian Judicial Indigenous Law Scholar Award (new) • Insolvency Institute of Canada Prize in Insolvency Studies (new) • Carolyn E. & Robert J. McCormick Indigenous Entrance Scholarship (revised) • Irene Lee Bursary In English (revised)* • Larry Lee Kinesiology Bursary (revised)* • Taylor Scholarship in Music (revised)* • Davison Graduate Award in Russian and Slavic Studies (revised) • T.S. McPherson Entrance Scholarship (revised)* • Terry and Myrna Daniels -

Detailed Information Including Programming from 2 Am

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 06:00 06:00 Local Morning Program 06:30 06:30 (5:30am start in selected markets) 07:00 Local Morning Program 07:00 07:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am CBC News: World Report 6/7/8/9 07:30 08:00 08:00 08:30 08:30 The Current 09:00 09:00 The House 09:30 Grownups… New Fire Stripped The Doc Project Short Cuts 09:30 The Sunday Edition 10:00 10:00 Day 6 10:30 Q the Summer 10:30 11:00 11:00 Under the The Irrelevant Podcast Playlist The 180 This is That The Debaters 11:30 Influence Show Grownups… 11:30 (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) 12:00 PM 12:00 PM Local Noon Hour Program Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 01:00 The Next Podcast The Debaters Spark 01:00 Your DNTO Vinyl Café Stories Radiolab Chapter Playlist (4 PT) 01:30 01:30 02:00 Wachtel on the Radiolab 02:00 The 180 Tapestry Spark Canada Live DNTO 02:30 Arts (3 PT, 4 MT) 02:30 03:00 03:00 Cross Country Writers & Quirks & Writers & Company Rewind My Playlist 03:30 in an Hour Company Quarks Wire Tap (5PT/MT/CT) 03:30 04:00 Local Afternoon Program 04:00 The Next Chapter Cross Country 04:30 (3 pm start in selected markets) 04:30 Checkup 05:00 05:00 Regional (1 PT, 2 MT, 3 CT, 5 AT) CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm 05:30 Performance 05:30 CBC News:The World This Weekend 06:00 CBC News: The World at Six 06:00 (7 AT) BBC 4 C'est la vie 06:30 06:30 As It Happens Short Cuts (7:30 AT) 07:00 In the Field + 07:00 07:30 Stripped By Design Doc Project New Fire AIH - Archive Randy Bachman's Living Out Loud 07:30 Vinyl Tap -

The Experience of Music Therapy Within Medical Assistance in Dying

EXIT MUSIC: THE EXPERIENCE OF MUSIC THERAPY WITHIN MEDICAL ASSISTANCE IN DYING by SarahRose Mary Black A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by SarahRose Mary Black, 2020 Exit Music: The Experience of Music Therapy within Medical Assistance in Dying SarahRose M. Black Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Music University of Toronto 2020 Abstract Since the 2015 legalization of medical assistance in dying (MAiD), healthcare professionals across the interdisciplinary spectrum have been exploring their roles within this practice, and a number of professions have created guidelines and policies to define their role(s). Many Canadian music therapists also found themselves implicated in care for those requesting MAiD. No prior research has been done to gain insight into the role of music therapy within the context of MAiD. This qualitative hermeneutic phenomenological study, the first of its kind, examines the experience of music therapy within medically assisted dying from three perspectives: the patient, their primary caregiver, and the music therapist/researcher. Ten cases that vary in duration of involvement of the music therapist, demographic, characteristics, and nature of the music therapy are presented through a hermeneutic phenomenological methodology lens. A total of 24 music therapy sessions and seven caregiver interviews were transcribed and analyzed. A total 28 researcher reflections were analyzed. The analysis of data revealed thematic trends of life reflection activated by the musical interaction (wherein the music functioned as a narrator and a trigger), control (over musical and ritualistic ii choices), communication and connectedness (with the self and others through music), and aesthetic pleasure (as a catalyst for therapeutic outcomes such as pain and symptom management). -

Gabriel Award Winners

2016 Catholic Academy Gabriel Award Winners RADIO Category 1: Entertainment...National or Local Release "Death and An Election In Pasco": Certificate of Merit Latino USA "Day 6: Sad YouTube, Music and Memory": Gabriel Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Category 6: Short Feature...Local Release Category 2: Arts...National or Local Release "The Eyeopener: Living on Empties": Gabriel Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Calgary "Song Travels with Michael Feinstein, Episode: Justin Kauflin": Gabriel South Carolina Public Radio "Religiously Devoted": Certificate of Merit WBVM Spirit FM 90.5, Tampa, Florida Category 3: Documentary...National Release Category 7: Religious...National Release "Why Do I Stay?": Gabriel WNYC Radio Rookies "Mary's Touch - Brian Caswell's Story": Gabriel Austin, Texas "The Doc Project: Whatever Happened to Scott?": Certificate of Merit Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Category 9: Ecumenical and Interreligious ...National or local Release Category 4: Documentary...Local Release "Tapestry: Educating Omar Khadr": Gabriel "Ideas: The Road to Damascus": Gabriel Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Canadian Broadcasting Corporation "The Sunday Edition : Answer Back, Brother": Certificate of Merit Category 11: News and Informational...Local Release Canadian Broadcasting Corporation "Why Left Turns Are So Deadly": Gabriel New York Public Radio - WNYC Category 5: Short Feature...National Release "Unreserved: Taking the First Steps on the Road to "Day 6: John Keller Interview": Gabriel Reconciliation": Certificate of Merit Canadian -

Evaluation Report, Safety in State Correctional Facilities, Is Available at 651-296-4708 Or

Safety in State Correctional Facilities 2020 EVALUATION REPORT Program Evaluation Division Office of the Legislative Auditor State of Minnesota Program Evaluation Division Evaluation Staff The Program Evaluation Division was created within James Nobles, Legislative Auditor the Office of the Legislative Auditor (OLA) in 1975. Judy Randall, Deputy Legislative Auditor The division’s mission, as set forth in law, is to determine the degree to which state agencies and Caitlin Badger programs are accomplishing their goals and Sarah Delacueva objectives and utilizing resources efficiently. Scott Fusco Will Harrison Topics for evaluations are approved by the Jody Hauer Legislative Audit Commission (LAC), which has Donald Hirasuna equal representation from the House and Senate and David Kirchner the two major political parties. However, evaluations Tavis Leighton by the office are independently researched by the Lucas Lockhart Legislative Auditor’s professional staff, and reports Ryan Moltz are issued without prior review by the commission or Jodi Munson Rodríguez any other legislators. Findings, conclusions, and Laura Schwartz recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views Katherine Theisen of the LAC or any of its members. Caitlin Zanoni OLA also has a Financial Audit Division that To obtain reports in electronic ASCII text, Braille, annually audits the financial statements of the State large print, or audio, call 651-296-4708. People with of Minnesota and, on a rotating schedule, audits state hearing or speech disabilities may call through agencies and various other entities. Financial audits Minnesota Relay by dialing 7-1-1 or 1-800-627-3529. of local units of government are the responsibility of the State Auditor, an elected office established in the To offer comments about our work or suggest an Minnesota Constitution. -

Contentious Politics and the 25Th January Egyptian Revolution

The London School of Economics and Political Science Contentious Politics and the 25th January Egyptian Revolution Neil Ketchley A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2014 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 44,982 words. 2 Abstract The three articles that make up this thesis consider the diverse forms of contentious politics and mass mobilization that emerged during the 25th January Egyptian Revolution in 2011 and its aftermath. The first article, discussing the eighteen days of anti-Mubarak protest, pays special attention to the position of the Egyptian army in and around Midan al-Tahrir, and recounts how protestors sought to co-opt and neutralize the threat posed by regime forces. It finds that fraternizing protestors developed a repertoire of contention that made situational, emotional claims on the loyalty of regime troops. -

RTDNA Canada Announces 2020 Network Award Winners

1 RTDNA Canada Announces 2020 Network Award Winners Toronto, ONTARIO – (June 9, 2020) - RTDNA Canada is pleased to recognize journalistic excellence with the winners of the 2020 RTDNA Canada Network Awards. RTDNA Canada Awards honour the best journalists, programs, stations and newsgathering organizations in radio, television and digital. Congratulations to the winners for their exceptional work! Please visit RTDNA Canada to view a highlight reel for each winner. 2020 RTDNA Canada Awards – Network Winners: Digital Best News App • CBC News – CBC News App Best Podcast • TSN – Durbano Best Sports App • Sportsnet – Sportsnet App Breaking News – Charlie Edwards Award • Globalnews.ca – The Arrest of Cameron Ortis Continuing Coverage – Ron Laidlaw Award • CBC News – Canada Votes (Digital) Data Storytelling Award • Global News – Tainted: Tainted Water Consortium Digital Media Award • CBC News: Indigenous Unit – Original Voices Diversity – Adrienne Clarkson Award • CBC Indigenous – Original Voices 2 Excellence in Social Media Award • Sportsnet – 2019 NBA Finals News – Live Special Events – Gord Sinclair Award • CBC News – Canada Votes (Election Night Live Special DIGITAL) Opinion and Commentary – Sam Ross Award • HuffPost Canada – Perspectives on Trudeau Blackface Incidents Sports – Feature Reporting • HuffPost Canada – The Race Never Ends for One of World's Top Ultra- Marathoners Multiplatform Dejero Award for Best Technical Innovation • CBC News – The National – Inside Syria Excellence in Innovation • CTV News – 2019 Election Campaign: Truth -

Empathy, Ethics and Aesthetics in Love + Radio Michelle Macklem Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

RadioDoc Review Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 4 January 2017 Empathy, ethics and aesthetics in Love + Radio Michelle Macklem Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/rdr Part of the American Studies Commons, Audio Arts and Acoustics Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Macklem, Michelle, Empathy, ethics and aesthetics in Love + Radio, RadioDoc Review, 3(1), 2017. doi:10.14453/rdr.v3i1.4 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Empathy, ethics and aesthetics in Love + Radio Abstract The podcast Love + Radio thrives on cultivating a kind of emotional tightrope, where the listener wavers from curiosity to contempt to empathy. The pe isodes “Jack and Ellen” and “The Living Room” have stark differences, particularly in terms of sound design, but their aesthetic and production values have a coherency that is exemplary of Love + Radio’s style. Sound is used to distinguish between ‘Ellen’, the subject, and ‘Jack’ her paedo-baiting alter ego. ‘Jack’ is created by pitch-shifting the voice of ‘Ellen’ down, instantly giving the story intrigue and also alluding to the clandestine nature of their work. “Jack and Ellen” is caught somewhere between a radio documentary and a swirling sample-based composition as the skilled musicality of the piece communicates a specific de itorial perspective, that is perhaps a glimpse of how the producers were affected during its creation. “The Living Room”, on the other hand, is sparse and neat.