Living in the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tese De Charles Ponte

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM CHARLES ALBUQUERQUE PONTE INDÚSTRIA CULTURAL, REPETIÇÃO E TOTALIZAÇÃO NA TRILOGIA PÂNICO Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem, da Universidade Estadual de Campinas, para obtenção do Título de Doutor em Teoria e História Literária, na área de concentração de Literatura e Outras Produções Culturais. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fabio Akcelrud Durão CAMPINAS 2011 i FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA ELABORADA POR CRISLLENE QUEIROZ CUSTODIO – CRB8/8624 - BIBLIOTECA DO INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM - UNICAMP Ponte, Charles, 1976- P777i Indústria cultural, repetição e totalização na trilogia Pânico / Charles Albuquerque Ponte. -- Campinas, SP : [s.n.], 2011. Orientador : Fabio Akcelrud Durão. Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. 1. Craven, Wes. Pânico - Crítica e interpretação. 2. Indústria cultural. 3. Repetição no cinema. 4. Filmes de horror. I. Durão, Fábio Akcelrud, 1969-. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. III. Título. Informações para Biblioteca Digital Título em inglês: Culture industry, repetition and totalization in the Scream trilogy. Palavras-chave em inglês: Craven, Wes. Scream - Criticism and interpretation Culture industry Repetition in motion pictures Horror films Área de concentração: Literatura e Outras Produções Culturais. Titulação: Doutor em Teoria e História Literária. Banca examinadora: Fabio Akcelrud Durão [Orientador] Lourdes Bernardes Gonçalves Marcio Renato Pinheiro -

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

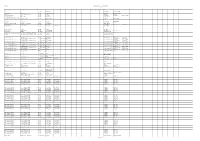

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

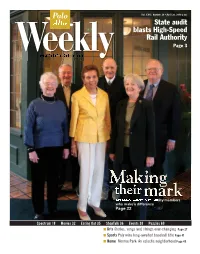

State Audit Blasts High-Speed Rail Authority Page 3

Palo 6°Ê888]Ê ÕLiÀÊÎäÊUÊ«ÀÊÎä]ÊÓä£äÊN 50¢ Alto State audit blasts High-Speed Rail Authority Page 3 www.PaloAltoOnline.com Making their mark Avenidas honors community members who make a difference Page 22 Spectrum 18 Movies 32 Eating Out 35 ShopTalk 36 Events 38 Puzzles 69 NArts Stories, songs and strings ever-changing Page 27 NSports Paly wins long-awaited baseball title Page 41 NHome Monroe Park: An eclectic neighborhood Page 49 JOIN US FOR THE GENTRY GALA FEATURING LOCAL GOURMET CUISINE, DANCING AND ENTERTAINMENT SATURDAY, MAY 15, 2010 • SHERATON HOTEL , PALO ALTO See the Latest Designs of The New Stanford Hospital Enjoy Live Entertainment Including: LATIN DANCE MARIACHI COUNTERPOINT STANFORD SYNCHRONIZED PERFORMANCES & LESSONS CARDENAL A CAPELLA SWIMMING Support Stanford Hospital & Clinics, Your Community Hospital VIP RECEPTION & GALA $250/person GALA $150/person Includes VIP Reception (Westin Palo Alto), Includes Admission to Gala (Sheraton Palo Alto) Admission to Gala (Sheraton Palo Alto), and Two Drinks Complimentary Valet Parking and Hosted Bar COCKTAIL ATTIRE For more information visit stanfordhospital.org/gala To RSVP, contact us at [email protected] or 650.721.2272 ABOUT STANFORD HOSPITAL & CLINICS Stanford Hospital & Clinics is known worldwide for advanced treatment of complex disorders in areas such as cardiovascular disease, cancer treatment, neurosciences, surgery and organ transplant. Consistently ranked among “America’s Best Hospitals” by U.S. News and World Report, Stanford is internationally recognized for -

Film, Philosophy Andreligion

FILM, PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION Edited by William H. U. Anderson Concordia University of Edmonton Alberta, Canada Series in Philosophy of Religion Copyright © 2022 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy of Religion Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942573 ISBN: 978-1-64889-292-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: "Rendered cinema fimstrip", iStock.com/gl0ck To all the students who have educated me throughout the years and are a constant source of inspiration. It’s like a splinter in your mind. ~ The Matrix Table of contents List of Contributors xi Acknowledgements xv Introduction xvii William H. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Félags- Og Mannvísindadeild

Félags- og mannvísindadeild MA-ritgerð Blaða- og fréttamennska Slægjur Undirflokkur hryllingsmynda Oddur Björn Tryggvason September 2009 Félags- og mannvísindadeild MA-ritgerð Blaða- og fréttamennska Slægjur Undirflokkur hryllingsmynda Oddur Björn Tryggvason September 2009 Leiðbeinandi: Guðni Elísson Nemandi: Oddur Björn Tryggvason Kennitala: 070278-5459 Ágrip Slægjur eru undirflokkur hryllingsmynda sem áttu blómaskeið sitt um miðbik áttunda áratugarins og fyrri hluta þess níunda. Þessar tegundir mynda þóttu ekki merkilegar út frá kvikmyndalegu sjónarmiði og voru harðlega gagnrýndar. Slægjurnar voru álitnar þrepinu ofar en klámmyndir. Auðvelt er að afskrifa myndirnar sökum einsleitni þeirra en þegar betur er að gáð má glögglega sjá að þær eru afsprengi umhverfisins og lýsandi dæmi um þann veruleika sem ákveðin kynslóð upplifði. Óvættirnir voru gjarnan táknrænir fyrir refsivendi óæskilegrar hegðunar og góð gildi ásamt sjálfsbjargarhvöt voru það sem þurfti til að lifa af. Félags- og stjórnmálalegar aðstæður höfðu sitt að segja í upprisu þessarra mynda og þær öðluðust vinsældir á umrótartíma í Bandaríkjunum. Fjallað verður um þessa tegund mynda og leitast við að varpa ljósi á menningarlegt gildi þeirra. bls. 3 Abstract Slasher films are a sub category within horror films that had it‘s glory days in the late seventies and early eighties. These films were not considered very noteworthy from a cinematic viewpoint and were harshly criticized by critics. Slasher films were thought to be one nocth above pornographic films. It‘s easy to write these films off because of their simplitcity but looking beneath the cover one can clearly see that these films are culturally significant and are indicative of a reality experienced by a certain generation. -

Por Título (.Pdf)

V I D I O T E C A DELEGAÇÃO LISBOA Listagem das obras por título TITULO REALIZADOR N_ORDEM CATEGORIA A FILHA DO MOSQUETEIRO STEVE BOYUM 3417 ACÇÃO/DRAMA A ONDA DOS SONHOS 2 MIKE ELLIOTT 3821 ACÇÃO/AVENTURA A PELE ONDE EU VIVO PEDRO ALMODÓVAR 3888 DRAMA/ROMANCE Á PROCURA DA TERRA DO NUNCA MARC FOSTER 2771 DRAMA/ROMANCE À PROVA DE FOGO JEAN-BAPTISTE LEONETTI 4427 ACÇÃO A SAGA TWILIGHT - LUA NOVA CHRIS EWITZ 3664 ACÇÃO/AVENTURA A SANGUE FRIO BENNETT MILLER 3040 ACÇÃO/AVENTURA A TEMPO E HORAS TOOD PHILLIPS 3820 COMÉDIA À TUA IMAGEM VIRGINIE SILLA 3439 THRILLER ABANDONADA CHUCK RUSSELL 2549 ACÇÃO/SUSPENSE ABC DA SEDUÇÃO ROBERT LUKETIC 3660 COMÉDIA ABEL DIEGO LUNA 4169 COMÉDIA/DRAMA ABRIL DESPEDAÇADO WALTER SALES 2748 DRAMA/ROMANCE ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS JENNIFER SAUNDERS 4603 COMÉDIA ACIDENTES SECRETOS ERIC NEVE 3630 ACÇÃO/AVENTURA ACONTECEU NA ARGENTINA CHRISTOPHER CHUL 3060 DRAMA/ROMANCE ACONTECEU NO OESTE SERGIO LEONE 2644 ACÇÃO/AVENTURA ACORDADO JOBY HAROLD 3452 THRILLER ACROSS THE UNIVERSE JULIE TAYMOR 3310 MUSICAL ACTO DE MATAR (O) JOSHUA OPPENHEIMER 4247 DOCUMENTÁRIO ADAM RENASCIDO PAUL SCHRADER 3714 ACÇÃO/AVENTURA ADEUS ÀS ARMAS FRANK BORZAGE 3037 ACÇÃO/AVENTURA AEROPLANO (O) 3250 COMÉDIA ÁFRICA MINHA SYDNEY POLLACK 3336 DRAMA/ROMANCE AGENTE SECRETO ALFRED HITCHCOCK 2553 ACÇÃO/SUSPENSE AGENTE VERMELHA (A) FRANCIS LAWRENCE 4682 ACÇÃO AGENTES DO DESTINO (OS) GEORGE NOLFI 3850 ACÇÃO/AVENTURA AGENTES UNIVERSITÁRIOS PHIL LORD, CHRISTOPHER MILLER 4300 COMÉDIA AGORA ONDE VAMOS (E) NADINE LABAKI 4062 ACÇÃO/AVENTURA ÁGUA DEEPA METHA 3149 DRAMA/ROMANCE -

Academy Invites 774 to Membership

MEDIA CONTACT [email protected] June 28, 2017 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ACADEMY INVITES 774 TO MEMBERSHIP LOS ANGELES, CA – The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is extending invitations to join the organization to 774 artists and executives who have distinguished themselves by their contributions to theatrical motion pictures. Those who accept the invitations will be the only additions to the Academy’s membership in 2017. 30 individuals (noted by an asterisk) have been invited to join the Academy by multiple branches. These individuals must select one branch upon accepting membership. New members will be welcomed into the Academy at invitation-only receptions in the fall. The 2017 invitees are: Actors Riz Ahmed – “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story,” “Nightcrawler” Debbie Allen – “Fame,” “Ragtime” Elena Anaya – “Wonder Woman,” “The Skin I Live In” Aishwarya Rai Bachchan – “Jodhaa Akbar,” “Devdas” Amitabh Bachchan – “The Great Gatsby,” “Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham…” Monica Bellucci – “Spectre,” “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” Gil Birmingham – “Hell or High Water,” “Twilight” series Nazanin Boniadi – “Ben-Hur,” “Iron Man” Daniel Brühl – “The Zookeeper’s Wife,” “Inglourious Basterds” Maggie Cheung – “Hero,” “In the Mood for Love” John Cho – “Star Trek” series, “Harold & Kumar” series Priyanka Chopra – “Baywatch,” “Barfi!” Matt Craven – “X-Men: First Class,” “A Few Good Men” Terry Crews – “The Expendables” series, “Draft Day” Warwick Davis – “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story,” “Harry Potter” series Colman Domingo – “The Birth of a Nation,” “Selma” Adam -

89Th Oscars® Nominations Announced

MEDIA CONTACT Academy Publicity [email protected] January 24, 2017 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Editor’s Note: Nominations press kit and video content available here 89TH OSCARS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED LOS ANGELES, CA — Academy President Cheryl Boone Isaacs, joined by Oscar®-winning and nominated Academy members Demian Bichir, Dustin Lance Black, Glenn Close, Guillermo del Toro, Marcia Gay Harden, Terrence Howard, Jennifer Hudson, Brie Larson, Jason Reitman, Gabourey Sidibe and Ken Watanabe, announced the 89th Academy Awards® nominations today (January 24). This year’s nominations were announced in a pre-taped video package at 5:18 a.m. PT via a global live stream on Oscar.com, Oscars.org and the Academy’s digital platforms; a satellite feed and broadcast media. In keeping with tradition, PwC delivered the Oscars nominations list to the Academy on the evening of January 23. For a complete list of nominees, visit the official Oscars website, www.oscar.com. Academy members from each of the 17 branches vote to determine the nominees in their respective categories – actors nominate actors, film editors nominate film editors, etc. In the Animated Feature Film and Foreign Language Film categories, nominees are selected by a vote of multi-branch screening committees. All voting members are eligible to select the Best Picture nominees. Active members of the Academy are eligible to vote for the winners in all 24 categories beginning Monday, February 13 through Tuesday, February 21. To access the complete nominations press kit, visit www.oscars.org/press/press-kits. The 89th Oscars will be held on Sunday, February 26, 2017, at the Dolby Theatre® at Hollywood & Highland Center® in Hollywood, and will be televised live on the ABC Television Network at 7 p.m. -

2012 and Will Not Have Completed Principal Photography During This Calendar Year

The Black List was compiled from the suggestions over 290 film executives, each of whom contributed the names of up to ten of their favorite scripts that were written in, or are somehow uniquely associated with, 2012 and will not have completed principal photography during this calendar year. This year, scripts had to receive at least six mentions to be included on the Black List. All reasonable effort has been made to confirm the information contained herein. The Black List apologizes for all misspellings, misattributions, incorrect representation identification, and questionable 2012 affiliations. It has been said many times, but it’s worth repeating: The Black List is not a “best of” list. It is, at best, a “most liked” list. FORWARD DRAFT DAY Rajiv Joseph, Scott Rothman 65 On the day of the NFL Draft, Bills General Manager Sonny Weaver has the opportunity to save football in Buffalo when he trades for the number one pick. He must quickly decide what he’s willing to sacrifice in pursuit of perfection as the lines between his personal and professional life become blurred. AGENCY Gersh, CAA AGENTS Lee Keele (Joseph), Chris Till, Bill Zotti (Rothman) MANAGEMENT Kaplan/Perrone (Joseph & Rothman) MANAGERS Josh Goldenberg, Aaron Kaplan PRODUCTION Montecito Pictures A COUNTRY OF STRANGERS Sean Armstrong 43 Based on true events. Inspector Geoff Harper conducts a forty year search for the Beaumont Children, three siblings taken from an Australian beach in January of 1966. AGENCY Verve AGENTS Aaron Hart, Adam Levine, Rob Herting, Bill Weinstein -

Ja He Elivät… Kuolivat… Jotain Siltä Väliltä?”

”JA HE ELIVÄT… KUOLIVAT… JOTAIN SILTÄ VÄLILTÄ…?” LOPETUKSEN TULKINTAA Aalto-yliopisto, PL 11000, 00076 AALTO www.aalto.fi Taiteen maisterin opinnäytteen tiivistelmä Tekijä Anni Pulkkinen Työn nimi “Ja he elivät… kuolivat… jotain siltä väliltä…?” – Lopetuksen tulkintaa Laitos Elokuvataiteen ja lavastustaiteen laitos Koulutusohjelma Elokuva- ja tv-käsikirjoitus Vuosi 2020 Sivumäärä 63 Kieli suomi Tiivistelmä Tämä opinnäyte käsittelee elokuvan lopetusta. Tarkasteluun asettuu lopun, eli viimeisen näytöksen kliimaksin jälkeinen pieni draamallinen yksikkö: elokuvan aivan viimeinen kohtaus tai kohtaukset. Lopetuksella on jo luonnostaan lähes pyhä asema elokuvakerronnassa, sillä se on viimeinen tarinan tapahtuma, jonka käsikirjoittaja kirjoittaa katsojalle nähtäväksi. Voisiko onnistuneelle lopetukselle määritellä tiettyjä tekijöitä? Opinnäyte koostuu kolmesta esseestä, joissa tarkastellaan Arrivalin (Yhdysvallat 2016), Titanicin (Yhdysvallat 1996) sekä Taru sormusten herrasta-trilogian viimeisen osan Kuninkaan paluun (Uusi-Seelanti-Yhdysvallat 2003) lopetuksia. Elokuvat on valittu analysoitavaksi sillä perusteella, että niiden lopetukset laukaisevat opinnäytteen kirjoittajassa aivan erityisen katarttisen reaktion. Esseiden ja koko työn punaisena lankana toimii trauman psykologinen ilmiö. On spekuloitu, että traumat ovat kaiken psyykkisen sairastamisen taustalla, ja siksi traumaa voi käyttää työkaluna tutkimaan ihmisen hyvinvointia – ja täten onnellisen elämän saloja. Mitä valittujen elokuvien lopetukset kertovat päähenkilöiden Louisen, Rosen -

Ficm Cat16 Todo-01

Contenido Gala Mexicana.......................................................................................................125 estrenos mexicanos.............................................................................126 Homenaje a Consuelo Frank................................................................... 128 Homenaje a Julio Bracho............................................................................136 ............................................................................................................ introducción 4 México Imaginario............................................................................................ 154 ................................................................................................................. Presentación 5 Cine Sin Fronteras.............................................................................................. 165 ..................................................................................... ¡Bienvenidos a Morelia! 6 Programa de Diversidad Sexual...........................................................172 ..................................................... Mensaje de la Secretaría de Cultura 7 Canal 22 Presenta............................................................................................... 178 Mensaje del Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía ������������9 14° Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia.............................11 programas especiales........................................................................ 179