The Role of Professional Child Care Providers in Preventing and Responding to Child Abuse and Neglect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Identify Rocks and Minerals

How to Identify Rocks and Minerals fluorite calcite epidote quartz gypsum pyrite copper fluorite galena By Jan C. Rasmussen (Revised from a booklet by Susan Celestian) 2012 Donations for reproduction from: Freeport McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation Friends of the Arizona Mining & Mineral Museum Wickenburg Gem & Mineral Society www.janrasmussen.com ii NUMERICAL LIST OF ROCKS & MINERALS IN KIT See final pages of book for color photographs of rocks and minerals. MINERALS: IGNEOUS ROCKS: 1 Talc 2 Gypsum 50 Apache Tear 3 Calcite 51 Basalt 4 Fluorite 52 Pumice 5 Apatite* 53 Perlite 6 Orthoclase (feldspar group) 54 Obsidian 7 Quartz 55 Tuff 8 Topaz* 56 Rhyolite 9 Corundum* 57 Granite 10 Diamond* 11 Chrysocolla (blue) 12 Azurite (dark blue) METAMORPHIC ROCKS: 13 Quartz, var. chalcedony 14 Chalcopyrite (brassy) 60 Quartzite* 15 Barite 61 Schist 16 Galena (metallic) 62 Marble 17 Hematite 63 Slate* 18 Garnet 64 Gneiss 19 Magnetite 65 Metaconglomerate* 20 Serpentine 66 Phyllite 21 Malachite (green) (20) (Serpentinite)* 22 Muscovite (mica group) 23 Bornite (peacock tarnish) 24 Halite (table salt) SEDIMENTARY ROCKS: 25 Cuprite 26 Limonite (Goethite) 70 Sandstone 27 Pyrite (brassy) 71 Limestone 28 Peridot 72 Travertine (onyx) 29 Gold* 73 Conglomerate 30 Copper (refined) 74 Breccia 31 Glauberite pseudomorph 75 Shale 32 Sulfur 76 Silicified Wood 33 Quartz, var. rose (Quartz, var. chert) 34 Quartz, var. amethyst 77 Coal 35 Hornblende* 78 Diatomite 36 Tourmaline* 37 Graphite* 38 Sphalerite* *= not generally in kits. Minerals numbered 39 Biotite* 8-10, 25, 29, 35-40 are listed for information 40 Dolomite* only. www.janrasmussen.com iii ALPHABETICAL LIST OF ROCKS & MINERALS IN KIT See final pages of book for color photographs of rocks and minerals. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

14-436 Statement of Adult Acting in Loco Parentis (As a Parent)

TANF/SFA FOR CHILDREN LIVING WITH UNRELATED ADULTS Statement of Adult Acting in Loco Parentis (as a Parent) Fill out this form if you are caring for a needy child you are not related to and you do not have court-ordered custody or guardianship of the child. SECTION 1. AGENCY INFORMATION (COMPLETED BY AGENCY STAFF ONLY) 1. COMMUNITY SERVICES OFFICE (CSO) 2. CASE MANAGER NAME 3. UNRELATED ADULT’S CLIENT ID NUMBER SECTION 2. INFORMATION ON ADULT CARING FOR THE CHILD (PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY) 4. LAST NAME 5. FIRST NAME 6. MIDDLE NAME 7. PHONE NUMBER (INCLUDE AREA CODE) ( ) 8. CURRENT ADDRESS (STREET, CITY, AND ZIP CODE) 9. PREVIOUS ADDRESS (STREET, CITY, AND ZIP CODE) SECTION 3. INFORMATION ON THE CHILD’S PARENTS (PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY) 10. NAME OF CHILD’S MOTHER 11. MOTHER’S PHONE NUMBER 12. MOTHER’S CURRENT OR LAST KNOWN ADDRESS ( ) 13. NAME OF CHILD’S FATHER 14. FATHER’S PHONE NUMBER 15. FATHER’S CURRENT OR LAST KNOWN ADDRESS ( ) SECTION 4. INFORMATION ABOUT YOUR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE CHILD (PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY) 16. Do you have permission from the child’s parents to care for the child? Yes No If yes, is it in w riting? Yes No 17. EXPLAIN HOW THE CHILD CAME TO LIVE WITH YOU 18. How long do you expect the child to live w ith you? 19. Are you planning to seek court-ordered custody or guardianship? Yes No SECTION 5. INFORMATION ABOUT THE CARE AND CONTROL OF A CHILD "In loco parentis" means in the place of a parent or instead of a We consider you as acting in loco parentis when: parent. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Teacher Resources – Trauma Responses in Early Teens and Adolescence

HOW CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE EXPERIENCE AND REACT TO TRAUMATIC EVENTS Booklet produced for the Victorian Bushfire Support and Training for Affected Schools Project May 2010 D1.2 This project was funded by the Australian Government. 1 AUSTRALIAN CHILD & ADOLESCENT TRAUMA, LOSS & GRIEF NETWORK THE AUTHORS JUSTIN KENARDY, ROBYNE LE BROCQUE, SONJA MARCH, ALEXANDRA DE YOUNG Justin Kenardy is Professor of Medicine and Psychology at the University of Queensland and Deputy Director of the Centre for National Research on Disability and Rehabilitation Medicine. He is a clinical psychologist and works primarily with children and adults who have experienced traumatic injury. Robyne Le Brocque is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for National Research on Disability and Rehabilitation Medicine. She is a health sociologist. Her interests are in the psychological and developmental impact of trauma on children and families. Sonja March is a Research Fellow at the Centre for National Research on Disability and Rehabilitation Medicine. She is a clinical psychologist and her work has focused on treatment of anxiety in children and adolescents, particularly using the internet. Alexandra De Young is a PhD Scholar at the School of Psychology, University of Queensland. She is a psychologist and her expertise lies in the impact of trauma on very young children. ACATLGN is a national collaboration to provide expertise, evidence-based resources and linkages to support children and their families through the trauma and grief associated with natural disasters and other adversities. It offers key resources to help school communities, families and others involved in the care of children and adolescents. -

Expanded Medical Leave Under the Families First Coronavirus

Expanded Medical Leave Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act Recognizes that it takes a Village to Raise a Child By: Alison Smith, Partner in Kelley Kronenberg’s Fort Lauderdale office. By now, most employers are familiar with, and have had to implement, aspects of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (“FFCRA”), (i.e., paid and/or family medical leave). Pursuant to the Emergency Family and Medical Leave Expansion Act (“EFMLA”), which as the name suggests, expands the Family and Medical Leave Act (“FMLA”), most employers with fewer than 500 employees are required to provide any employee who has worked for their company for at least 30 days, up to 12 weeks of job-protected leave. The first 10 days are unpaid (unless the employee requests paid sick leave or uses accrued leave time), and the remainder is paid for up to another 10 weeks (assuming the employee has not already used or exhausted FMLA leave for other qualifying reasons). Pay provided must be no less than two-thirds of the employee's regular rate, capped at $200 per day and $10,000 in the aggregate. This leave is specifically permitted so that the employee (who must not be able to work or telecommute), can provide child care for a son or daughter under the age of 18 if that child’s school or place of care is closed, or the childcare provider is unavailable due to a public health emergency (or, if the child is 18 years of age or older, has a mental or physical disability and is incapable of self-care because of that disability). -

Children's Participation in Child Protection

CHILDREN’S PARTICIPATION IN CHILD PROTECTION Tool 4 www.keepingchildrensafe.org.uk Copyright © Keeping Children Safe Coalition 2011 Graphics & Layout www.ideenweberei.com Produced by the Keeping Children Safe Coalition Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................2 Module One: Children recognise what is child abuse ................................................................................10 Exercise 1.1: Children’s rights .............................................................................................. 11 Exercise 1.2: Feeling safe and unsafe .................................................................................. 18 Exercise 1.3: Understanding child abuse ............................................................................. 22 Module Two: Children keeping themselves and others safe ..............................................................................................38 Exercise 2.1: Talking about feelings ..................................................................................... 38 Exercise 2.2: Decision-making ............................................................................................. 44 Exercise 2.3: Children keeping children safe ....................................................................... 49 Module Three: Making organisations feel safe for children................................................................................................56 -

Conduct and Behavior Problems: Intervention and Resources for School Aged Youth

An introductory packet on Conduct and Behavior Problems: Intervention and Resources for School Aged Youth The Center is co-directed by Howard Adelman and Linda Taylor and operates under the auspices of the School Mental Health Project, Dept. of Psychology, UCLA, Box 951563, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1563 (310) 825-3634 Fax: (310) 206-5895; E-mail: [email protected] Permission to reproduce this document is granted. Please cite source as the Center for Mental Health in Schools at UCLA. Please reference this document as follows: Center for Mental Health in Schools at UCLA. (2008). Conduct and Behavior Problems Related to School Aged Youth. Los Angeles, CA: Author. Copies may be downloaded from: http://smhp.psych.ucla.edu If needed, copies may be ordered from: Center for Mental Health in Schools UCLA Dept. of Psychology P.O. Box 951563 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1563 The Center encourages widespread sharing of all resources Overview In this introductory packet, the range of conduct and behavior problems are described using fact sheets and the classification scheme from the American Pediatric Association. Differences in intervention needed are discussed with respect to variations in the degree of problem manifested and include exploration of environmental accommodations, behavioral strategies, and medication. For those readers ready to go beyond this introductory presentation or who are interested in the topics of school violence, crisis response, or ADHD, we also provide a set of references for further study and, as additional resources, agencies and websites are listed that focus on these concerns. 1 Conduct and Behavior Problems: Interventions and Resources This introductory packet contains: I. -

Romeo and Juliet PART ONE (Easy Reader Edition).Pdf

Copyright © 2013. Saddleback Educational Publishing. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law. EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/6/2017 1:38 PM via OSAGE CO SCHOOL DIST R1 AN: 641677 ; Hutchison, Patricia, Shakespeare, William.; Romeo and Juliet Account: 076-081 ROMEO AND JULIET William Shakespeare – ADAPTED BY – Patricia Hutchison Copyright © 2013. Saddleback Educational Publishing. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law. EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 4/6/2017 1:38 PM via OSAGE CO SCHOOL DIST R1 AN: 641677 ; Hutchison, Patricia, Shakespeare, William.; Romeo and Juliet Romeo & Juliet_RL1_int.inddAccount: 076-081 1 7/2/13 4:26 PM Copyright ©2013 by Saddleback Educational Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, scanning, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. SADDLEBACK EDUCATIONAL PUBLISHING and any associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Saddleback Educational Publishing. ISBN-13: 978-1-62250-712-2 ISBN-10: 1-62250-712-6 eBook: 978-1-61247-963-7 Printed in Guangzhou, China 0000/CA00000000 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5 Copyright © 2013. Saddleback Educational Publishing. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. -

The Relationship Between Child Protection Workers and School Social Workers

St. Catherine University SOPHIA Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers School of Social Work 3-2014 The Relationship Between Child Protection Workers and School Social Workers Daniel S. Gibbel St. Catherine University Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Gibbel, Daniel S.. (2014). The Relationship Between Child Protection Workers and School Social Workers. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/ msw_papers/317 This Clinical research paper is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Social Work at SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers by an authorized administrator of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: Relationships Between Social Service Colleagues The Relationship Between Child Protection Workers and School Social Workers Daniel S. Gibbel MSW Clinical Research Paper Presented to the Faculty of School of the Social of Social Work St. Catherine University and the University of St. Thomas St. Paul, Minnesota In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Social Work Committee Members Karen Carlson, Ph.D. (Chair) Dana Hagemann, LSW Tricia Sedlacek MSW, LGSW The Clinical Research Project is a graduation requirement for MSW students at St. Catherine University/University of St. Thomas School of Social Work in St. Paul, Minnesota and is conducted within a nine-month time frame to demonstrate facility with basic social research methods. Students must independently conceptualize a research problem, formulate a research design that is approved by a research committee and the university Institutional Review Board, implement the project, and publicly present the findings of the study. -

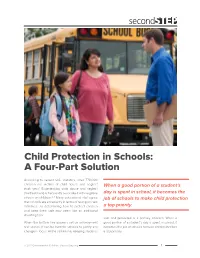

Child Protection in Schools: a Four-Part Solution

Child Protection in Schools: A Four-Part Solution According to recent U.S. statistics, over 770,000 children are victims of child abuse and neglect When a good portion of a student’s each year.1 Experiencing child abuse and neglect (maltreatment) is frequently associated with negative day is spent in school, it becomes the effects on children.2, 3 Many educational staff agree job of schools to make child protection that schools are at capacity in terms of taking on new initiatives, so determining how to protect children a top priority. and keep them safe may seem like an additional daunting task. safe and protected is a primary concern. When a When the bottom line appears set on achievement good portion of a student’s day is spent in school, it test scores, it can be hard for schools to justify any becomes the job of schools to make child protection change in focus. At the same time, keeping students a top priority. © 2014 Committee for Children ∙ SecondStep.org 1 priority and motivate staff to implement skills learned Four Components of School-Based Child Protection in training. Research by Yanowitz and colleagues6 underscores the importance of emphasizing policies Policies and Procedures and procedures in child abuse training within the Sta Training school setting. Student Lessons Family Education Administrators must assess their current child protection policies, Research indicates the most effective way to procedures and practices to develop do this is by training adults—all school staff and a comprehensive child protection caregivers—and teaching students skills.4, 5, 6 This can be accomplished by creating and implementing strategy for their school.