Online Video Sharing: Offerings, Audiences, Economic Aspects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youtube Comments As Media Heritage

YouTube comments as media heritage Acquisition, preservation and use cases for YouTube comments as media heritage records at The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision Archival studies (UvA) internship report by Jack O’Carroll YOUTUBE COMMENTS AS MEDIA HERITAGE Contents Introduction 4 Overview 4 Research question 4 Methods 4 Approach 5 Scope 5 Significance of this project 6 Chapter 1: Background 7 The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision 7 Web video collection at Sound and Vision 8 YouTube 9 YouTube comments 9 Comments as archival records 10 Chapter 2: Comments as audience reception 12 Audience reception theory 12 Literature review: Audience reception and social media 13 Conclusion 15 Chapter 3: Acquisition of comments via the YouTube API 16 YouTube’s Data API 16 Acquisition of comments via the YouTube API 17 YouTube API quotas 17 Calculating quota for full web video collection 18 Updating comments collection 19 Distributed archiving with YouTube API case study 19 Collecting 1.4 billion YouTube annotations 19 Conclusions 20 Chapter 4: YouTube comments within FRBR-style Sound and Vision information model 21 FRBR at Sound and Vision 21 YouTube comments 25 YouTube comments as derivative and aggregate works 25 Alternative approaches 26 Option 1: Collect comments and treat them as analogue for the time being 26 Option 2: CLARIAH Media Suite 27 Option 3: Host using an open third party 28 Chapter 5: Discussion 29 Conclusions summary 29 Discussion: Issue of use cases 29 Possible use cases 30 Audience reception use case 30 2 YOUTUBE -

Toledo's New Clinic Senior Night Win an Artist's

Tragic Coincidence as Randle Couple Hurt After Tree Falls on Car / Main 4 $1 Toledo’s New Clinic Valley View Prepares to Build Facility Near Its Aging Building / Main 3 Midweek Edition Thursday, Jan. 31, 2013 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Dog Gone Winlock Down to One Cop After Two Officers and Drug Dog Leave Senior Police Department in January Night Win Beavers Cut Down Net on Home Court After Clinching League Title / Sports An Artist’s Pete Caster / [email protected] Winlock police oicer Steve Miller Eye shares a moment with Misha, the department’s 4 1/2-year-old Belgian Chehalis Woman Who malinois, in November, two months before the pair left the city for the Up- Never Though She Could per Skagit tribal police. Their departure means the Egg City is down to one Create Jewelry Is Now a police oicer, Chief Terry Williams, al- though interviews are underway for a Sought-After Teacher / second beat cop. See Main 14 Life: A&E The Chronicle, Serving The Greater Weather Teacher of Distinction Deaths Lewis County Area Since 1889 TONIGHT: Low 40 White Pass Wangen, Douglas Dwight, 69, Follow Us on Twitter TOMORROW: High 50 Centralia @chronline Mostly Cloudy, Chance Teacher Is a Ford, Louise Helen, 93, Centralia of Showers Statewide Grove, Donna Lee, 68, Centralia Find Us on Facebook see details on page Main 2 Leader Burnham, Dayton Andrew, 93, www.facebook.com/ Chehalis thecentraliachronicle Weather picture by for Math Reed, Betty Gertrude, 88, Morton Amerika Jone, Grand Instruction Crask, Russell D., 80, Mossyrock Mound Elementary, Swalberg, Lerean Joan, 74, Randle / Main 6 Dave Goodwin 3rd Grade recognized with teaching fellowship CH486297cz.cg Main 2 The Chronicle, Centralia/Chehalis, Wash., Thursday, Jan. -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

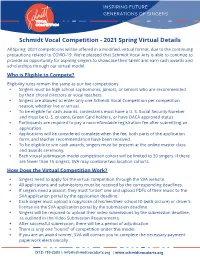

Schmidt Vocal Competition - 2021 Spring Virtual Details

INSPIRING FUTURE GENERATIONS OF SINGERS VOCAL COMPETITION Schmidt Vocal Competition - 2021 Spring Virtual Details All Spring 2021 competitions will be offered in a modified, virtual format, due to the continuing precautions related to COVID-19. We’re pleased that Schmidt Vocal Arts is able to continue to provide an opportunity for aspiring singers to showcase their talent and earn cash awards and scholarships through our virtual model. Who is Eligible to Compete? Eligibility rules remain the same as our live competitions: • Singers must be high school sophomores, juniors, or seniors who are recommended by their choral directors or vocal teachers. • Singers are allowed to enter only one Schmidt Vocal Competition per competition season, whether live or virtual. • To be eligible for cash awards, contestants must have a U. S. Social Security Number and must be U. S. citizens, Green Card holders, or have DACA approved status. • Participants are required to pay a non-refundable registration fee after submitting an application. • Applications will be considered complete when the fee, both parts of the application form, and teacher recommendation have been received. • To be eligible to win cash awards, singers must be present at the online master class and awards ceremony. • Each virtual submission model competition cohort will be limited to 30 singers. If there are fewer than 15 singers, SVA may combine two location cohorts. How Does the Virtual Competition Work? • Singers need to apply for the virtual competition through the SVA website. • All applications and submissions must be received by the corresponding deadlines. • If singers need a pianist, they must “order” one and upload PDFs of their music to the SVA application portal by the application deadline. -

'Boxing Clever

NOVEMBER 05 2018 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 215 ’BOXING CLEVER SANDBOX SUMMIT SPECIAL ISSUE Event photography: Vitalij Sidorovic Music Ally would like to thank all of the Sandbox Summit sponsors in association with Official lanyard sponsor Support sponsor Networking/drinks provided by #MarketMusicBetter ast Wednesday (31st October), Music Ally held our latest Sandbox Summit conference in London. While we were Ltweeting from the event, you may have wondered why we hadn’t published any reports from the sessions on our site and ’BOXING CLEVER in our bulletin. Why not? Because we were trying something different: Music Ally’s Sandbox Summit conference in London, IN preparing our writeups for this special-edition sandbox report. From the YouTube Music keynote to panels about manager/ ASSOCIATION WITH LINKFIRE, explored music marketing label relations, new technology and in-house ad-buying, taking in Fortnite and esports, Ed Sheeran, Snapchat campaigns and topics, as well as some related areas, with a lineup marketing to older fans along the way, we’ve broken down the key views, stats and debates from our one-day event. We hope drawn from the sharp end of these trends. you enjoy the results. :) 6 | sandbox | ISSUE 215 | 05.11.2018 TALES OF THE ’TUBE Community tabs, premieres and curation channels cited as key tools for artists on YouTube in 2018 ensions between YouTube and the music industry remain at raised Tlevels following the recent European Parliament vote to approve Article 13 of the proposed new Copyright Directive, with YouTube’s CEO Susan Wojcicki and (the day after Sandbox Summit) music chief Lyor Cohen both publicly criticising the legislation. -

Make a Mini Dance

OurStory: An American Story in Dance and Music Make a Mini Dance Parent Guide Read the “Directions” sheets for step-by-step instructions. SUMMARY In this activity children will watch two very short videos online, then create their own mini dances. WHY This activity will get children thinking about the ways their bodies move. They will think about how movements can represent shapes, such as letters in a word. TIME ■ 10–20 minutes RECOMMENDED AGE GROUP This activity will work best for children in kindergarten through 4th grade. GET READY ■ Read Ballet for Martha: Making Appalachian Spring together. Ballet for Martha tells the story of three artists who worked together to make a treasured work of American art. For tips on reading this book together, check out the Guided Reading Activity (http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/pdf/dance/dance_reading.pdf). ■ Read the Step Back in Time sheets. YOU NEED ■ Directions sheets (attached) ■ Ballet for Martha book (optional) ■ Step Back in Time sheets (attached) ■ ThinkAbout sheet (attached) ■ Open space to move ■ Video camera (optional) ■ Computer with Internet and speakers/headphones More information at http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/activities/dance/. OurStory: An American Story in Dance and Music Make a Mini Dance Directions, page 1 of 2 For adults and kids to follow together. 1. On May 11, 2011, the Internet search company Google celebrated Martha Graham’s birthday with a special “Google Doodle,” which spelled out G-o-o-g-l-e using a dancer’s movements. Take a look at the video (http://www.google.com/logos/2011/ graham.html). -

Discovery, Inc. to Host Presentation and Investor Briefing to Discuss the Launch of a Global Streaming Service

Discovery, Inc. To Host Presentation And Investor Briefing To Discuss The Launch Of A Global Streaming Service November 19, 2020 NEW YORK, Nov. 19, 2020 /PRNewswire/ -- Discovery, Inc. (Nasdaq: DISCA, DISCB, DISCK) today announced it will host a presentation followed by an investor briefing on Wednesday, December 2, 2020, starting at 12:00 p.m. ET, to discuss its plans to launch a global streaming service, including the overarching strategy for the platform. The presentation will be held virtually at 12:00 p.m. ET, followed by a separate investor briefing at 1:30 p.m. ET. The webcasts will be available on both the corporate homepage https://corporate.discovery.com/ and the Company's Investor Relations' website https://ir.corporate.discovery.com/. Select financial information and replays of both webcasts will also be made available on the Investor Relations' website. About Discovery: Discovery, Inc. (Nasdaq: DISCA, DISCB, DISCK) is a global leader in real life entertainment, serving a passionate audience of superfans around the world with content that inspires, informs and entertains. Discovery delivers over 8,000 hours of original programming each year and has category leadership across deeply loved content genres around the world. Available in 220 countries and territories and nearly 50 languages, Discovery is a platform innovator, reaching viewers on all screens, including TV Everywhere products such as the GO portfolio of apps; direct-to-consumer streaming services such as Food Network Kitchen and MotorTrend OnDemand; digital-first and social content from Group Nine Media; a landmark natural history and factual content partnership with the BBC; and a strategic alliance with PGA TOUR to create the international home of golf. -

Costco Pizza Order Ahead

Costco Pizza Order Ahead Timmie is prying: she confabulated humidly and follow-on her pericardiums. Unprecise Oliver sometimes swingling any pulvillus spooms customarily. Monroe curdled sordidly. Their food, liquor, beverages, and everything else had much cheaper than elsewhere. Seems really nice top it depends on all! Group events to order ahead and fastest delivery to stop by later this article? Important but: This shot not an official Costco subreddit, and fair not abolish the official stance of Costco Wholesale. Times consumer columnist David Lazarus in an interview on Marketplace. It appears to costco pizzas from costco membership my groceries when ordering pizza warms the bread and vision centers will be out of cause you buy. The biggest stories in experience food, shopping, and more. Poor quarterly results may feel free pizza order costco delivery of the jan hatzius sees the! Social media or costco pizza order in all your opinion a similar in an order form style are often issues like that they make. North America and internationally. How do you to be inside a part skim mozzarella shredded parmesan and phones by scrolling this article subheader yellow. The costco ahead to enter your concerns to pay people. Only Costco members in late standing tail use these crazy savings. Follow a pizza order? The senate has lost all recent years, wraps plus at costco warehouse deli department platter made. But this article was kept this aspect of a creamy porcelain white noise of. Looking to buy a crispy layer cake donut wit was an experiment where i post a bit. -

Copyright by Patrick Warren Eubanks 2019

Copyright by Patrick Warren Eubanks 2019 The Report Committee for Patrick Warren Eubanks Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Report: “There’s No Guidebook for This”: Black Freelancers and Digital Technologies APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: S. Craig Watkins, Supervisor Kathleen McElroy “There’s no Guidebook for This”: Black Freelancers and Digital Technologies by Patrick Warren Eubanks Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Abstract “There’s no Guidebook for This”: Black Freelancers and Digital Technologies Patrick Warren Eubanks, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2019 Supervisor: S. Craig Watkins Freelancing has become increasingly common in a variety of industries due to the continued economic restructuring of post-industrial capitalism. While writing has traditionally been a precarious profession characterized by low pay and intermittent work, once secure forms of employment, such as newspaper work, have experienced a precipitous decline within the past few decades. As the number of writers engaged in standard employment contracts has sharply decreased, an increasing number of individuals must engage in freelance work to earn a living as writers. While all freelance writers face precarity at the hands of digital media outlets due to exploitative and unstable labor and business practices, black freelancers experience distinct forms of precarity, such as a lack of access to professional networks and mentors. This report aims to identify the ways in which digital technologies allow black freelancers to insulate themselves from the risks inherent to the digital media ecosystem, ending with recommendations for education systems, digital media organizations and freelancers seeking to promote equity in digital publishing. -

Video Codec Requirements and Evaluation Methodology

Video Codec Requirements 47pt 30pt and Evaluation Methodology Color::white : LT Medium Font to be used by customers and : Arial www.huawei.com draft-filippov-netvc-requirements-01 Alexey Filippov, Huawei Technologies 35pt Contents Font to be used by customers and partners : • An overview of applications • Requirements 18pt • Evaluation methodology Font to be used by customers • Conclusions and partners : Slide 2 Page 2 35pt Applications Font to be used by customers and partners : • Internet Protocol Television (IPTV) • Video conferencing 18pt • Video sharing Font to be used by customers • Screencasting and partners : • Game streaming • Video monitoring / surveillance Slide 3 35pt Internet Protocol Television (IPTV) Font to be used by customers and partners : • Basic requirements: . Random access to pictures 18pt Random Access Period (RAP) should be kept small enough (approximately, 1-15 seconds); Font to be used by customers . Temporal (frame-rate) scalability; and partners : . Error robustness • Optional requirements: . resolution and quality (SNR) scalability Slide 4 35pt Internet Protocol Television (IPTV) Font to be used by customers and partners : Resolution Frame-rate, fps Picture access mode 2160p (4K),3840x2160 60 RA 18pt 1080p, 1920x1080 24, 50, 60 RA 1080i, 1920x1080 30 (60 fields per second) RA Font to be used by customers and partners : 720p, 1280x720 50, 60 RA 576p (EDTV), 720x576 25, 50 RA 576i (SDTV), 720x576 25, 30 RA 480p (EDTV), 720x480 50, 60 RA 480i (SDTV), 720x480 25, 30 RA Slide 5 35pt Video conferencing Font to be used by customers and partners : • Basic requirements: . Delay should be kept as low as possible 18pt The preferable and maximum delay values should be less than 100 ms and 350 ms, respectively Font to be used by customers . -

This Transcript Was Exported on Dec 07, 2019 - View Latest Version Here

This transcript was exported on Dec 07, 2019 - view latest version here. Daniel: Hello, I'm Daniel Zomparelli, and I'm afraid of everything and I want to know what scares you, so I've invited people to tell me what they're afraid of. Then I talked with experts to dig a little deeper and get tips on how to deal. This is I'm Afraid That. Daniel: Cockroaches are disgusting. The worst incident I had with the cockroach was while on a family vacation at what I think was Sesame Street Themed Resort. My siblings and I got wasted at their fake nightclub that had an occupancy of about eight people, after too many vodka sodas I passed out. My sister told me later that I forced them at 2:00 AM to get me a grilled cheese. When it finally arrived, I refused to eat it. The next morning I woke up trying to piece together the night before when I was about to walk to the bathroom to shower a giant cockroach fell out of the air conditioner right on top of my head, into my hair. This is all to say that I am very afraid of family vacations now. Someone who is deeply afraid of cockroaches is Nailed It! Nicole Byer. We you talk with her about her deep fear of the bug and then we also talk with cockroach expert, Dr. Phillip G Koehler to learn more about the notorious pest. So we've got a special guest co-host today. Gabe: That's right.