Nurture: the Ring That Holds the Keys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fro F M V M°J° Nixon Is Mojo Is in A

TW O G R EA T W H A T'S FILMS FROMI HAPPENING S O U TH T O VIC AFR ICA DUNLO P 9A 11A The Arts and Entertainment Section of the Daily Nexus OF NOTE THIS WEEK 1 1 « Saturday: Don Henley at the Santa Barbara County Bowl. 7 p.m. Sunday: The Jefferson Airplane re turns. S.B. County Bowl, 3 p.m. Tuesday: kd. long and the reclines, country music from Canada. 8 p.m. at the Ventura Theatre Wednesday: Eek-A-M ouse deliv ers fun reggae to the Pub. 8 p.m. Definately worth blowing off Countdown for. Tonight: "Gone With The Wind," The Classic is back at Campbell Hall, 7 p.m. Tickets: $3 w/student ID 961-2080 Tomorrow: The Second Animation -in n i Celebration, at the Victoria St. mmm Theatre until Oct. 8. Saturday: The Flight of the Eagle at Campbell Hall, 8 p.m. H i « » «MI HBfi MIRiM • ». frOf M v M°j° Nixon is Mojo is in a College of Creative Studies' Art vJVl 1T1.J the man your band with his Gallery: Thomas Nozkowski' paint ings. Ends Oct. 28. University Art Museum: The Tt l t f \ T/'\parents prayed partner, Skid Other Side of the Moon: the W orldof Adolf Wolfli until Nov. 5; Free. J y l U J \ J y ou'd never Roper, who Phone: 961-2951 Women's Center Gallery: Recent Works by Stephania Serena. Large grow up to be. plays the wash- color photgraphs that you must see to believe; Free. -

Rsd21 Drop 1 Remainders 4 July Customer Version

STOCK REMAINING FROM RSD21 DROP 1, JUNE 12, 2021 Items in bold are RSD Drop 1, everything else is back catalogue by the same artists THIS LIST UPDATED 4/7/21; MORE BACK CATALOGUE IN THE NEXT VERSION ITEM ARTIST TITLE FORMAT INFO PRICE £ 1. AC/DC Through The Mists Of Time/Witches Spell 12" clear vinyl Single Classic rock 20.99 2. AC/DC PWR/UP Ltd edn yellow vinyl LP Classic rock 34.99 (NOT RSD) 3. AIR People in the City 12" Picture Disc Electronic 22.75 4. AIR 10 000 H2 Legend 2LP Electronic 22.99 (NOT RSD) 5. ALARM, THE Spirit of '58 7" Punk 12.25 6. ALARM, THE Celtic Folklore Live in London and California 1988 LP Punk 22.99 (NOT RSD) 7. ALARM, THE Equals (2018) LP + poster Punk 18.99 (NOT RSD) 8. ALBERT COLLINS & Albert Collins & Barrelhouse Live 1LP transparent red / solid white / Rock 21.99 BARRELHOUSE black 9. AMORPHOUS ANDROGYNOUS, The World Is Full Of Plankton 10" Techno 14.99 THE 10. ANIMAL COLLECTIVE Prospect Hummer 12" EP Indie 25.49 11. ANTI-FLAG 20/20 Division 1 LP - Coloured Rock 26.25 12. ANTI-FLAG The Bright Lights of America 2LP green vinyl, this is #0462 Includes poster 21.99 (NOT RSD) 13. ANTI-FLAG The General Strike LP Rock 18.99 (NOT RSD) 14. ANTI-FLAG Live acoustic at 11th Street Records LP Rock WAS (RSD16) 20.99 NOW 16.80 15. ARNIE LOVE & THE LOVELETTS Invisible Wind 12" Soul 11.49 16. ART BLAKEY AND HIS JAZZ Chippin' In 2XLP with insert Jazz 39.49 MESSENGERS 17. -

Music History Lecture Notes Modern Rock 1960 - Today

Music History Lecture Notes Modern Rock 1960 - Today This presentation is intended for the use of current students in Mr. Duckworth’s Music History course as a study aid. Any other use is strictly forbidden. Copyright, Ryan Duckworth 2010 Images used for educational purposes under the TEACH Act (Technology, Education and Copyright Harmonization Act of 2002). All copyrights belong to their respective copyright holders, • Rock’s classic act The Beatles • 1957 John Lennon meets Paul McCartney, asks Paul to join his band - The Quarry Men • George Harrison joins at end of year - Johnny and the Moondogs The Beatles • New drummer Pete Best - The Silver Beetles • Ringo Star joins - The Beatles • June 6, 1962 - audition for producer George Martin • April 10, 1970 - McCartney announces the group has disbanded Beatles, Popularity and Drugs • Crowds would drown of the band at concerts • Dylan turned the Beatles on to marijuana • Lennon “discovers” acid when a friend spikes his drink • Drugs actively shaped their music – alcohol & speed - 1964 – marijuana - 1966 – acid - Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery tour – heroin in last years Beatles and the Recording Process • First studio band – used cutting-edge technology – recordings difficult or impossible to reproduce live • Use of over-dubbing • Gave credibility to rock albums (v. singles) • Incredible musical evolution – “no group changed so much in so short a time” - Campbell Four Phases of the Beatles • Beatlemania - 1962-1964 • Dylan inspired seriousness - 1965-1966 • Psychedelia - 1966-1967 • Return to roots - 1968-1970 Beatlemania • September 1962 – “Love me Do” • 1964 - “Ticket to Ride” • October 1963 – I Want To Hold your Hand • Best example • “Yesterday” written Jan. -

Extensions of Remarks E503 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

April 3, 2014 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E503 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS REMEMBERING BOB CASALE OF HONORING MR. NICHOLAS P. a $22 million 125,000 square foot campus in DEVO DINAPOLI Westminster, Colorado, creating an additional 100 high paying jobs. HON. STEVE ISRAEL I extend my deepest congratulations to Trimble Navigation for receiving the Business HON. TIM RYAN OF NEW YORK Recognition Award from the Jefferson County OF OHIO IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Economic Development Corporation. I thank IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Thursday, April 3, 2014 you for your commitment to innovation, high standards and quality products. Thursday, April 3, 2014 Mr. ISRAEL. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to honor Mr. Nicholas P. DiNapoli, an esteemed f Mr. RYAN of Ohio. Mr. Speaker, I rise today citizen of my congressional district who holds NATIONAL SCHOOL LUNCH to honor the remarkable life of Bob Casale, the distinction of being a lifelong resident of PROGRAM who passed away on February 17, 2014, at the Town of North Hempstead. Mr. DiNapoli the age of sixty-one. Bob was raised in Akron, was born on April 6, 1924, to Pete and Jea- HON. TED POE nette DiNapoli in Roslyn Heights, New York, Ohio. He led an exemplary life while in pursuit OF TEXAS of his dream of writing, producing, and per- and has resided in Albertson, New York since IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES forming music. Bob helped create a body of 1953. He is a New Yorker, born and bred. Thursday, April 3, 2014 work with his band Devo that put the ‘‘new’’ in After graduating from Roslyn public schools, new wave music. -

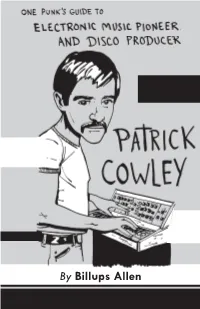

By Billups Allen Billups Allen Is a Record Store Clerk Who Spent His Formative Years in and Around the Washington D.C

By Billups Allen Billups Allen is a record store clerk who spent his formative years in and around the Washington D.C. punk scene. He graduated from the University of Arizona with a creative writing major and film minor. He currently lives in Memphis, Tennessee where he publishes Cramhole zine, contributes regularly to Razorcake, Lunchmeat, and Ugly Things, and writes fiction (cramholezine.com, billupsallen@ gmail.com) Illustrations by Danny Martin: Zines, murals , stickers, woodcuts, and teachin’ screen printing at a community college on the side. (@DannyMartinArt) Zine design by Todd Taylor Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. One Punk’s Guide to Patrick Cowley originally appeared in Razorcake #107, released in December 2018/January 2019. This zine is made possible in part by support by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles Arts Commission. Printing Courtesy of Razorcake Press razorcake.org n 1978 a DJ subscription-only remix of the already popular Donna Summer song “I Feel Love” went out in the mail. It was 15:43 long. The bass line was looped so overdubbed synthesizer effects could be added. This particular version of the song went largely unnoticed by the general public and did nothing to make producer Patrick Cowley a household name. But dancers in nightclubs reacted. They may have been unaware and/or unconcerned about what they were hearing, but they reacted. -

What Were the Forces That Led to the Rise of New Wave?

Are We Not New Wave? Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s Theo Cateforis http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=152565 The University of Michigan Press, 2011 Q&A with Theo Cateforis, author of Are We Not New Wave? Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s New wave emerged at the turn of the 1980s as a pop music movement cast in the image of punk rock's sneering demeanor, yet rendered more accessible and sophisticated. Artists such as the Cars, Devo, the Talking Heads, and the Human League leapt into the Top 40 with a novel sound that broke with the staid rock clichés of the 1970s and pointed the way to a more modern pop style. In Are We Not New Wave? Theo Cateforis provides the first musical and cultural history of the new wave movement, charting its rise out of mid- 1970s punk to its ubiquitous early 1980s MTV presence and downfall in the mid-1980s. The book also explores the meanings behind the music's distinctive traits—its characteristic whiteness and nervousness; its playful irony, electronic melodies, and crossover experimentations. Cateforis traces new wave's modern sensibilities back to the space-age consumer culture of the late 1950s/early 1960s. Theo Cateforis is Assistant Professor of Music History and Cultures in the Fine Arts Department at Syracuse University. His research is in the areas of American Music, Popular Music Studies, and Twentieth-Century Art Music. He was editor of the anthology The Rock History Reader. The University of Michigan Press: What were the forces that led to the rise of new wave? Theo Cateforis: New wave initially circulated as a synonym for the punk rock movement that emerged in the mid-1970s. -

![[ ALTERNATIVE by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 408 ] 28 DAYS >> SONG](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9812/alternative-by-artist-no-of-tunes-408-28-days-song-3289812.webp)

[ ALTERNATIVE by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 408 ] 28 DAYS >> SONG

[ ALTERNATIVE by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 408 ] 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO A >> STARBUCKS ALIEN ANT FARM >> GLOW ALIEN ANT FARM >> MOVIES ALIEN ANT FARM >> SMOOTH CRIMINAL {K} ALL AMERICAN REJECTS >> GIVES YOU HELL {K} ANDREW W K >> WE WANT FUN ANDROIDS >> DO IT WITH MADONNA {K} ARCTIC MONKEYS >> I BET YOU LOOK GOOD ON THE DANCE FLOOR AREA 7 >> START MAKING SENSE ASHLEE SIMPSON >> LA LA {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> GIRLFRIEND {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> HERE'S TO NEVER GROWING UP {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> MY HAPPY ENDING {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> SK8ER BOI {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> SMILE {K} BABY ANIMALS >> RUSH YOU BEASTIE BOYS >> BODY MOVIN BEASTIE BOYS >> INTERGALATIC BEN FOLDS FIVE >> ROCKIN' THE SUBURBS BIG AUDIO DYNAMITE >> RUSH BLACK KEYS >> LONELY BOY {K} BLIND MELON >> NO RAIN BLINK 182 >> ALL THE SMALL THINGS {K} BLINK 182 >> BORED TO DEATH BLINK 182 >> DAMMIT BLINK 182 >> I MISS YOU {K} BLINK 182 >> MAN OVERBOARD {K} BLINK 182 >> ROCK SHOW BLINK 182 >> WHAT'S MY AGE BLOODHOUND GANG >> FIRE WATER BURN BLUR >> CRAZY BEAT BLUR >> SONG 2 BODY ROCKERS >> I LIKE THE WAY {K} BODYJAR >> FALL TO THE GROUND {K} BODYJAR >> TOO DRUNK TO DRIVE BUSTED >> WHAT I GO TO SCHOOL FOR CAKE >> SHORT SKIRT - LONG JACKET CALLING >> OUR LIVES CARDIGANS >> MY FAVOURITE GAME CITIZEN KING >> BETTER DAYS COLDPLAY >> DON'T PANIC COLDPLAY >> EVERY TEARDROP IS A WATERFALL COLDPLAY >> PARADISE COLDPLAY >> SPEED OF SOUND {K} COLDPLAY >> TALK {K} CORNERSHOP -

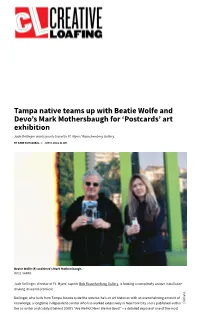

Tampa Native Teams up with Beatie Wolfe and Devo's Mark

Tampa native teams up with Beatie Wolfe and Devo’s Mark Mothersbaugh for ‘Postcards’ art exhibition Jade Dellinger wants you to travel to Ft. Myers’ Rauschenberg Gallery. BY GABE ECHAZABAL — JUN 4, 2021 11 AM Beatie Wolfe (R) and Devo’s Mark Mothersbaugh. ROSS HARRIS Jade Dellinger, director of Ft. Myers’ superb Bob Rauschenberg Gallery, is hosting a completely unique installation making its world premiere. Dellinger, who hails from Tampa, boasts quite the resume; he’s an art historian with an overwhelming amount of knowledge, a longtime independent curator who has worked extensively in New York City and a published author. AsDonate the co-writer and catalyst behind 2008’s “Are We Not Men? We Are Devo!”—a detailed expose of one of the most ingenious and innovative bands of all time—Dellinger’s expertise crosses many boundaries. His fascination withPrivacy Devo doesn’t stop at the band’s quirky music. The band’s aesthetic, its approach to art, its films and its overall approach all spoke to Dellinger in equal parts so his enthusiasm for the installation on display in Ft. Meyers through Aug. 8. Postcards for Democracy Through Aug. 8 at Bob Rauschenberg Gallery Florida SouthWestern State College, 8099 College Pkwy Bldg. L, Fort Myers. During an exhibition, Gallery hours are: Monday-Friday, 10 a.m.-4 p.m.; Saturday, 11 a.m.-3 p.m. (closed Sundays and holidays) (239) 489-9313; rauschenberggallery.com “Postcards for Democracy” is a trailblazing, interactive concept hatched by none other than Devo frontman, Mark Mothersbaugh. The composer, songwriter and visual artist paired with British singer-songwriter and innovative artist Beatie Wolfe to concoct an idea meant to draw much-deserved attention to one of the country’s most underappreciated institutions, the U.S. -

What Is Post-Punk?

What is Post-Punk? A Genre Study of Avant-Garde Pop, 1977-1982 Mimi Haddon Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montréal April 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Ph.D. in Musicology © Mimi Haddon 2015 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... vi Résumé ......................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... viii List of Musical Examples ................................................................................................................ x List of Diagrams and Tables ........................................................................................................... xi List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... xii INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Genre ........................................................................................................ 4 Genre as Musical Style .......................................................................................................... -

Educator Guide: Mark Mothersbaugh, Myopia September 25, 2015 – January 9, 2016

Educator Guide: Mark Mothersbaugh, Myopia September 25, 2015 – January 9, 2016 artist bio “I got a pair of glasses • Born: 1950, Akron Ohio when I was seven and I • Education: Went to Kent State University in 1968, started as a printmaker • Musician,composer, singer, artist and co-founder of DEVO. saw the world-it all just • Composer for movie and television scores including “Pee-wee’s Playhouse,” “The Lego Mov- came into focus in one ie” and many films by the director Wes Anderson. • His process often starts with a drawing—he then uses the computer to generate prints, rugs, moment.” animations, sculptures, etc. exhibition • This exhibition includes documentation and music from Mark Mothersbaugh’s DEVO days as well as prints, drawings, paintings, sculptures, rugs and video animations. It also includes newly- produced musical and sculptural installations and most notably, a life-long series of postcard- sized works. • The title of the exhibition, Myopia, refers to the vision defect Mothersbaugh was diagnosed with when he was 7. • He began working on “Beautiful Mutants” series in the early 1990s. He digitally edits vintage photographs to present the symmetrical reflection of one side of a subject’s body and face. He places many of these in old daguerreotype frames to heighten the eerie effect. This series explores symmetry and how humans are not really symmetrical. • Mothersbaugh began the Orchestrion series while writing music for Wes Anderson’s movie, “Moonrise Kingdom”. He collected antique duck calls and dismantled organ pipes to create these electronic, music machines. materials • Digitally altered photographs, antique frames, a redesigned automobile and ceramic sculptures. -

Neo-Darwinism and Evo-Devo: an Argument for Theoretical Pluralism in Evolutionary Biology

Neo-Darwinism and Evo-Devo: An Argument for Theoretical Pluralism in Evolutionary Biology Lindsay R. Craig Temple University There is an ongoing debate over the relationship between so-called neo-Darwinism and evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) that is motivated in part by the possibility of a theoretical synthesis of the two (e.g., Amundson 2005; Brigandt and Love 2010; Laubichler 2010; Minelli 2010; Pigliucci and Müller 2010). Through analysis of the terms and arguments employed in this debate, I argue that an alternative line of argument has been missed. Specifically, I use the terms of this debate to argue that a relative significance issue (Beatty 1995, 1997) exists and reflects a theoretical pluralism that is likely to remain. 1. Introduction The relatively new field of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) continues to attract considerable attention from biologists, philosophers, and historians, in part, because work in this field demonstrates that impor- tant changes are underway within biology (e.g., Gilbert, Opitz and Raff 1996; Love 2003; Amundson 2005; Burian 2005a; Müller and Newman 2005; Laubichler 2007, 2010; Müller 2007; Pigliucci 2007, 2009; Minelli 2010). Though studies of development and evolution were closely connected during the 19th century, continued work in genetics fostered a general split between the two during the first decades of the twentieth century (e.g., Allen 1978; Gilbert 1978; Mayr and Provine 1980; Gilbert, Opitz and Raff 1996). Consequently, embryology and developmental biology did not play a significant role in the development of so-called neo-Darwinism1 during the Thanks to Richard Burian, Michael Dietrich, and Robert Richardson for comments on earlier versions of this paper. -

Devo Shout Mp3, Flac, Wma

Devo Shout mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Shout Country: Italy Released: 1984 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1517 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1908 mb WMA version RAR size: 1284 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 858 Other Formats: DTS AAC MP4 ADX DMF WAV MP3 Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Shout 3:16 2 The Satisfied Mind 3:08 3 Don't Rescue Me 3:06 4 The 4th Dimension 4:24 5 C'mon 3:16 6 Here To Go 3:18 7 Jurisdiction Of Love 3:00 8 Puppet Boy 3:10 9 Please Please 3:04 Are You Experienced? 10 3:15 Written-By – Jimi Hendrix 11 Growing Pains 3:45 12 Shout (E-Z Listening Muzak Version 1) 4:12 Companies, etc. Marketed By – American Recordings Phonographic Copyright (p) – Warner Bros. Records Inc. Copyright (c) – Warner Bros. Records Inc. Copyright (c) – Devo Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Infinite Zero Copyright (c) – Infinite Zero Pressed By – WEA Mfg. Olyphant – W170 Credits Art Direction – Vigon Seireni* Art Direction [Rerelease] – Sherry Leight Engineer – Robert Casale Engineer [Assistant] – Ed Delena* Mastered By [Originally] – Steve Marcussen* Mixed By – Mike Shipley (tracks: 1 to 9) Photography By – Karen Filter Producer – Devo Programmed By [Additional Emulator Programs] – Al Norvath*, Bill Wolfer Remastered By – Bill Inglot, Dan Hersch Technician [Technical Assistance] – Jim Mothersbaugh Written-By – Devo (tracks: 1, 2, 4 to 6, 8, 9, 11, 12), Mark Mothersbaugh (tracks: 3, 7) Notes Originally released in 1984. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 9362-43094-2 0 Matrix / Runout: wea mfg.