Mark Mothersbaugh, Composer: an Appreciation Written by Daniel Goldmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fro F M V M°J° Nixon Is Mojo Is in A

TW O G R EA T W H A T'S FILMS FROMI HAPPENING S O U TH T O VIC AFR ICA DUNLO P 9A 11A The Arts and Entertainment Section of the Daily Nexus OF NOTE THIS WEEK 1 1 « Saturday: Don Henley at the Santa Barbara County Bowl. 7 p.m. Sunday: The Jefferson Airplane re turns. S.B. County Bowl, 3 p.m. Tuesday: kd. long and the reclines, country music from Canada. 8 p.m. at the Ventura Theatre Wednesday: Eek-A-M ouse deliv ers fun reggae to the Pub. 8 p.m. Definately worth blowing off Countdown for. Tonight: "Gone With The Wind," The Classic is back at Campbell Hall, 7 p.m. Tickets: $3 w/student ID 961-2080 Tomorrow: The Second Animation -in n i Celebration, at the Victoria St. mmm Theatre until Oct. 8. Saturday: The Flight of the Eagle at Campbell Hall, 8 p.m. H i « » «MI HBfi MIRiM • ». frOf M v M°j° Nixon is Mojo is in a College of Creative Studies' Art vJVl 1T1.J the man your band with his Gallery: Thomas Nozkowski' paint ings. Ends Oct. 28. University Art Museum: The Tt l t f \ T/'\parents prayed partner, Skid Other Side of the Moon: the W orldof Adolf Wolfli until Nov. 5; Free. J y l U J \ J y ou'd never Roper, who Phone: 961-2951 Women's Center Gallery: Recent Works by Stephania Serena. Large grow up to be. plays the wash- color photgraphs that you must see to believe; Free. -

Subculture Magazine - Alternative Music and Culture Magazine

Subculture Magazine - alternative music and culture magazine. The ultimate ...c, darkwave, synthpop, alternative and post punk music. always on the edge. User Password Sign Up | Forgot Password Thursday, Dec 08 , 2005 Devo - Live 1980 (DVD) Posted :Thu, Dec 8th, 2005 00:20:24 Devo Devo - Live 1980 (DVD) Target Video Review By : Vivien Weimar With 80s nostalgia being de rigueur these days, the time is ripe for a DEVO reunion. The reclusive new wave band usually doesn't tour much as original founder Mark Mothersbaugh has since moved on to creating commercials and soundtracks at his Los Angeles production company Mutato Muzika (that fantastically weird space-ship-looking building on Sunset Boulevard) along with the other Devo members save Jerry Casale who has been directing videos for such bands as the Foo Fighters and Soundgarden. However, this summer Devo got together and played limited dates all across the country--and this fall they released Live 1980, a full-length concert video shot at the Phoenix Theatre in Petaluma, CA on August 17, 1980. Complete with white uniforms, blue background screen and "energy domes" (don't you dare call them flower-pot hats), Devo play the hits off of their albums, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We are Devo!, Duty Now For the Future and Freedom of Choice. Twenty-one songs are featured in this 75-minute disc including the classic MTV staple "Whip It", the oft-covered "Girl U Want", and their own covers of Johnny River's classic "Secret Agent Man" and the Rolling Stones "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction". -

Dead Zone Back to the Beach I Scored! the 250 Greatest

Volume 10, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television FAN MADE MONSTER! Elfman Goes Wonky Exclusive interview on Charlie and Corpse Bride, too! Dead Zone Klimek and Heil meet Romero Back to the Beach John Williams’ Jaws at 30 I Scored! Confessions of a fi rst-time fi lm composer The 250 Greatest AFI’s Film Score Nominees New Feature: Composer’s Corner PLUS: Dozens of CD & DVD Reviews $7.95 U.S. • $8.95 Canada �������������������������������������������� ����������������������� ���������������������� contents ���������������������� �������� ����� ��������� �������� ������ ���� ���������������������������� ������������������������� ��������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����� ��� ��������� ����������� ���� ������������ ������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ��������������������� �������������������� ���������������������������������������������� ����������� ����������� ���������� �������� ������������������������������� ���������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������� ������������������������������� �������������������������� ���������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������������������������ �������������������������� -

2007-09-06.Pdf

2 BUZZ 09.06.07 daily.titan daily.titan BUZZ 09.06.07 3 BEAUTIFUL MUTANTS An artist who sees beauty his own way NERO ZERO IF YOU LIVED HERE ... The Buzz Editor: The Daily Titan 714.278.3373 LOCKED & LOADED Jennifer Caddick The Buzz Editorial 714.278.5426 [email protected] FOR MISFIRE Executive Editor: Editorial Fax 714.278.4473 AND Ian Hamilton The Buzz Advertising Director of 714.278.3373 [email protected] WE ASKED A Advertising Fax 714.278.2702 Advertising: The Buzz , a student publication, is a supplemental Stephanie Birditt insert for the Cal State Fullerton Daily Titan. It is printed MEXICAN every Thursday. The Daily Titan operates independently Assistant Director of of Associated Students, College of Communications, Advertising: CSUF administration and the CSU system. The Daily Titan Sarah Oak has functioned as a public forum since inception. Unless implied by the advertising party or otherwise stated, advertising in the Daily Titan is inserted by commercial Production: activities or ventures identified in the advertisements Jennifer Caddick themselves and not by the university. Such printing is not to be construed as written or implied sponsorship, Account Executives: endorsement or investigation of such commercial Nancy Sanchez enterprises. Juliet Roberts Copyright ©2006 Daily Titan /FX4VNNFS%SJOL1SJDFTr̾BOEPWFS 2 BUZZ 09.06.07 daily.titan daily.titan BUZZ 09.06.07 3 Fairfax District PHOTO BY CELIA CASTANON PHOTO BY CELIA CASTANON Inside Reserve vintage art and book gallery. A view of Canter’s Deli BY CELIA CASTANON at Canter’s. “And most celebrities definitely a place to find and recreate from $40 to $300, the art is actually are claustrophobic, this is not for Daily Titan Staff Writer come in around three or four in the a vintage look. -

Entertainment 87 ENTERTAINMENT

Enroll at uclaextension.edu or call (800) 825-9971 Entertainment 87 ENTERTAINMENT Sneak Preview See the most highly anticipated new films prior to public release, specially selected for our Sneak Preview audience. Our seasoned moderators lead engaging Q&As with actors, directors, writers, and producers, giving you an inside look at the making of each film. Sneak Preview starts January 29 and presents 10 new films. Page 87. Past films and guests have included 87 FILM & TV MUSIC Marriage Story with director Ford v Ferrari with director 88 Business & Management 95 Film Scoring Noah Baumbach James Mangold of Entertainment 96 Music Business If Beale Street Could Talk with director Dolemite Is My Name with screenwriters Barry Jenkins Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski 89 Entertainment Project 97 Music Production Management A Hidden Life with actor Valerie Pachner Diane with actor Mary Kay Place 90 Acting Above: Q&A with (left to right) moderator Pete Hammond and director Robert Kenner at Sneak Preview. 91 Cinematography For weekly updates, visit entertainment.uclaextension.edu/sneak-preview. 91 Directing 92 Film & TV Development FILM TV UL 700 Film & TV Free Networking Opportunities 93 Producing For more information call (310) 825-9064, email for Entertainment Studies [email protected], or visit Certificate Students 95 Post-Production entertainment.uclaextension.edu. Does your project need a director, cinematographer, screenwriter, actor, producer, composer, or other crew FILM TV 804.2 member? Would you like to meet other like-minded Sneak Preview: students who have the same business or career goals Contemporary Films and Filmmakers as you? This is the perfect opportunity to meet your 2.0 CEUs fellow certificate students and make important connec- For more information call (310) 825-9064. -

Rsd21 Drop 1 Remainders 4 July Customer Version

STOCK REMAINING FROM RSD21 DROP 1, JUNE 12, 2021 Items in bold are RSD Drop 1, everything else is back catalogue by the same artists THIS LIST UPDATED 4/7/21; MORE BACK CATALOGUE IN THE NEXT VERSION ITEM ARTIST TITLE FORMAT INFO PRICE £ 1. AC/DC Through The Mists Of Time/Witches Spell 12" clear vinyl Single Classic rock 20.99 2. AC/DC PWR/UP Ltd edn yellow vinyl LP Classic rock 34.99 (NOT RSD) 3. AIR People in the City 12" Picture Disc Electronic 22.75 4. AIR 10 000 H2 Legend 2LP Electronic 22.99 (NOT RSD) 5. ALARM, THE Spirit of '58 7" Punk 12.25 6. ALARM, THE Celtic Folklore Live in London and California 1988 LP Punk 22.99 (NOT RSD) 7. ALARM, THE Equals (2018) LP + poster Punk 18.99 (NOT RSD) 8. ALBERT COLLINS & Albert Collins & Barrelhouse Live 1LP transparent red / solid white / Rock 21.99 BARRELHOUSE black 9. AMORPHOUS ANDROGYNOUS, The World Is Full Of Plankton 10" Techno 14.99 THE 10. ANIMAL COLLECTIVE Prospect Hummer 12" EP Indie 25.49 11. ANTI-FLAG 20/20 Division 1 LP - Coloured Rock 26.25 12. ANTI-FLAG The Bright Lights of America 2LP green vinyl, this is #0462 Includes poster 21.99 (NOT RSD) 13. ANTI-FLAG The General Strike LP Rock 18.99 (NOT RSD) 14. ANTI-FLAG Live acoustic at 11th Street Records LP Rock WAS (RSD16) 20.99 NOW 16.80 15. ARNIE LOVE & THE LOVELETTS Invisible Wind 12" Soul 11.49 16. ART BLAKEY AND HIS JAZZ Chippin' In 2XLP with insert Jazz 39.49 MESSENGERS 17. -

Keeping the Score the Impact of Recapturing North American Film and Television Sound Recording Work

Keeping the Score The impact of recapturing North American film and television sound recording work December 2014 [This page is intentionally left blank.] Keeping the Score Table of Contents Acknowledgments 2 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Precarious work in a shifting industry 7 From full-time to freelance 7 A dignified standard set by decades of organizing 9 Musicians in a Twenty-First Century studio system 12 What is a “major studio” anyhow? 12 Composers squeezed in the middle: the rise of the “package deal” 15 Chasing tax credits 17 A profitable industry 19 The “last actors” feel the pain 21 Recording employment slipping away 21 Where has recording gone? 24 Recording the score as “an afterthought” 25 Hollywood provides quality employment – for most 26 Bringing work back: the debate thus far 28 A community weakened by the loss of music 33 Case Study: Impact on the Los Angeles regional economy 33 Impact on the cultural fabric 35 Breaking the social compact 36 Federal subsidies 36 Local subsidies 37 Cheating on employment 38 Lionsgate: a new major roars 39 Reliance on tax incentives 41 Wealth – and work – not shared 41 Taking the high road: what it could mean 43 Conclusion and Recommendations 44 Recommendations to policy makers 44 Recommendations to the industry 46 Endnotes 47 laane: a new economy for all 1 Keeping the Score Acknowledgments Lead author: Jon Zerolnick This report owes much to many organizations and individuals who gave generously of their time and insights. Thanks, first and foremost, to the staff and members of the American Federation of Musicians, including especially Local 47 as well as the player conference the Recording Musicians Association. -

Music History Lecture Notes Modern Rock 1960 - Today

Music History Lecture Notes Modern Rock 1960 - Today This presentation is intended for the use of current students in Mr. Duckworth’s Music History course as a study aid. Any other use is strictly forbidden. Copyright, Ryan Duckworth 2010 Images used for educational purposes under the TEACH Act (Technology, Education and Copyright Harmonization Act of 2002). All copyrights belong to their respective copyright holders, • Rock’s classic act The Beatles • 1957 John Lennon meets Paul McCartney, asks Paul to join his band - The Quarry Men • George Harrison joins at end of year - Johnny and the Moondogs The Beatles • New drummer Pete Best - The Silver Beetles • Ringo Star joins - The Beatles • June 6, 1962 - audition for producer George Martin • April 10, 1970 - McCartney announces the group has disbanded Beatles, Popularity and Drugs • Crowds would drown of the band at concerts • Dylan turned the Beatles on to marijuana • Lennon “discovers” acid when a friend spikes his drink • Drugs actively shaped their music – alcohol & speed - 1964 – marijuana - 1966 – acid - Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery tour – heroin in last years Beatles and the Recording Process • First studio band – used cutting-edge technology – recordings difficult or impossible to reproduce live • Use of over-dubbing • Gave credibility to rock albums (v. singles) • Incredible musical evolution – “no group changed so much in so short a time” - Campbell Four Phases of the Beatles • Beatlemania - 1962-1964 • Dylan inspired seriousness - 1965-1966 • Psychedelia - 1966-1967 • Return to roots - 1968-1970 Beatlemania • September 1962 – “Love me Do” • 1964 - “Ticket to Ride” • October 1963 – I Want To Hold your Hand • Best example • “Yesterday” written Jan. -

Extensions of Remarks E503 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

April 3, 2014 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E503 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS REMEMBERING BOB CASALE OF HONORING MR. NICHOLAS P. a $22 million 125,000 square foot campus in DEVO DINAPOLI Westminster, Colorado, creating an additional 100 high paying jobs. HON. STEVE ISRAEL I extend my deepest congratulations to Trimble Navigation for receiving the Business HON. TIM RYAN OF NEW YORK Recognition Award from the Jefferson County OF OHIO IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Economic Development Corporation. I thank IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Thursday, April 3, 2014 you for your commitment to innovation, high standards and quality products. Thursday, April 3, 2014 Mr. ISRAEL. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to honor Mr. Nicholas P. DiNapoli, an esteemed f Mr. RYAN of Ohio. Mr. Speaker, I rise today citizen of my congressional district who holds NATIONAL SCHOOL LUNCH to honor the remarkable life of Bob Casale, the distinction of being a lifelong resident of PROGRAM who passed away on February 17, 2014, at the Town of North Hempstead. Mr. DiNapoli the age of sixty-one. Bob was raised in Akron, was born on April 6, 1924, to Pete and Jea- HON. TED POE nette DiNapoli in Roslyn Heights, New York, Ohio. He led an exemplary life while in pursuit OF TEXAS of his dream of writing, producing, and per- and has resided in Albertson, New York since IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES forming music. Bob helped create a body of 1953. He is a New Yorker, born and bred. Thursday, April 3, 2014 work with his band Devo that put the ‘‘new’’ in After graduating from Roslyn public schools, new wave music. -

The Haverford Journal

The Haverford Journal The Haverford Journal Volume 3, Issue 1 April 2007 Volume 3, Issue 1 The Cultural Politics of British Opposition to Italian Opera, 1706-1711 Veronica Faust ‘06 Childbirth in Medieval Art Kate Phillips ‘06 Baudrillard, Devo, and the Postmodern De-evolution of the Simulation James Weissinger ‘06 Politics and the Representation of Gender and Power in Rubens’s The Disembarkation at Marseille from The Life of Marie de’ Medici April 2007 Aaron Wile ‘06 “Haverford’s best student work in the humanities and social sciences.” April 2007 (Vol. 3, Issue 1) 1 The Haverford Journal Volume 3, Issue 1 February 2007 Published by The Haverford Journal Editorial Board Managing Editors Pat Barry ‘07 Julia Erdosy ‘07 Board Members Production Leigh Browning ‘07 Sam Kaplan ‘10 Julia McGuire ‘09 Sarah Walker ‘08 Faculty Advisor Phil Bean Associate Dean of the College The Haverford Journal is published annually by the Haverford Journal Editorial Board at Haverford College, 370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, PA 19041. The Journal was founded in the spring of 2004 by Robert Schiff in an effort to showcase some of Haverford’s best student work in the humanities and social sciences. Student work appearing in The Haverford Journal is selected by the Editorial Board, which puts out a call for papers at the end of every spring semester. Entries are judged on the basis of academic merit, clarity of writing, persuasiveness, and other factors that contribute to the quality of a given work. All student papers submitted to the Journal are numbered and classified by a third party and then distributed to the Board, which judges the papers without knowing the names or class years of the papers’ authors. -

Art Terrorism in Ohio: Cleveland Punk, the Mimeograph Revolution, Devo, Zines, Artists’ Periodicals, and Concrete Poetry, 1964-2011

Art Terrorism in Ohio: Cleveland Punk, The Mimeograph Revolution, Devo, Zines, Artists’ Periodicals, and Concrete Poetry, 1964-2011. The Catalog for the Inaugural Exhibition at Division Leap Gallery. Part 1: Cleveland Punk [Nos. 1-22] Part 2: Devo, Evolution, & The Mimeograph Revolution [Nos. 23-33] Part 3: Zines, Artists’ Periodicals, The Mimeograph Revolution & Poetry [Nos.34-100] This catalog and exhibition arose out two convictions; that the Cleveland Punk movement in the 70’s is one of the most important and overlooked art movements of the late 20th century, and that it is fruitful to consider it in context of its relationship with several other equally marginalized contemporary postwar Ohio art movements in print; The Mimeograph Revolution, the zine movement, concrete poetry, and mail art. Though some pioneering music criticism, notably the work of Heylin and Savage, has placed Cleveland as being of central importance to the proto-punk narrative, it remains largely marginalized as an art movement. This may be because of geographical bias; Cleveland is a long way from New York or London. This is despite the fact that the bands involved were heavily influenced by previous art movements, especially the electric eels, who, informed by Viennese Aktionism, Albert Ayler, and theories of anti- music, were engaged in a savage form of performance art which they termed “Art Terrorism” which had no parallel at the time (and still doesn’t). It is tempting to imagine what response the electric eels might have had in downtown New York in the early 70’s, being far more provocative than their distant contemporaries Suicide. -

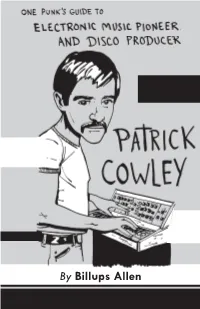

By Billups Allen Billups Allen Is a Record Store Clerk Who Spent His Formative Years in and Around the Washington D.C

By Billups Allen Billups Allen is a record store clerk who spent his formative years in and around the Washington D.C. punk scene. He graduated from the University of Arizona with a creative writing major and film minor. He currently lives in Memphis, Tennessee where he publishes Cramhole zine, contributes regularly to Razorcake, Lunchmeat, and Ugly Things, and writes fiction (cramholezine.com, billupsallen@ gmail.com) Illustrations by Danny Martin: Zines, murals , stickers, woodcuts, and teachin’ screen printing at a community college on the side. (@DannyMartinArt) Zine design by Todd Taylor Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. One Punk’s Guide to Patrick Cowley originally appeared in Razorcake #107, released in December 2018/January 2019. This zine is made possible in part by support by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles Arts Commission. Printing Courtesy of Razorcake Press razorcake.org n 1978 a DJ subscription-only remix of the already popular Donna Summer song “I Feel Love” went out in the mail. It was 15:43 long. The bass line was looped so overdubbed synthesizer effects could be added. This particular version of the song went largely unnoticed by the general public and did nothing to make producer Patrick Cowley a household name. But dancers in nightclubs reacted. They may have been unaware and/or unconcerned about what they were hearing, but they reacted.