Géricault. Raft of the Medusa Initial Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2007 Newsletter

Spring 2007 Collecting China Interdisciplinary symposium expands dialog on Chinese art objects The Newsletter of the University of Delaware Department of Art History 1 Contents Spring 2007 Editor in Chief and Photo Editor: From the Chair From the Chair | 3 Undergraduate Student Linda Pellecchia News | 15 Titles Editor: David M. Stone No doubt, you’ve noticed that the Art History newsletter has changed its Art History Club | 15 Art Director: Don Shenkle look and now has a name, Insight. The department, launched more than Undergraduate Awards | 15 Editorial Coordinator: forty years ago, has fl ourished and Insight allows us to spread the news Connee McKinney of our extraordinary record of accomplishments. Some news builds on Secretarial Assistance: Eileen Larson, traditional strengths. Other items refl ect exciting new directions. Our Deb Morris, Tina Trimble focus on American art will expand next year with the arrival of a new Graduate Student News | 16 “Collecting ‘China’” — Insight is produced by the Department colleague in the history of African American art and another in the 19th An International Gem | 4 Graduate Awards | 16 of Art History as a service to alumni and 20th-century art of the United States. Our curriculum has, on the Graduate Student News | 16 and friends of the Department. We are other hand, expanded globally beyond America and Europe. We now Graduate Degrees Granted | 17 always pleased to receive your opin- teach the arts and architecture of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Art News from Alumni | 18 ions and ideas. Please contact Eileen History undergraduate and graduate students have garnered prestigious Larson, Old College 318, University of grants and awards. -

Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Dorothy Johnson GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los ANGELES For my parents, Alice and John Winter, and for Johnny Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748 — 1825). The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, 1818 Benedicte Gilman, Editor (detail). Oil on canvas, 87.2 x 103 cm (34% x 40/2 in.). Elizabeth Burke Kahn, Production Coordinator Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum (87.PA.27). Jeffrey Cohen, Designer Lou Meluso, Photographer Frontispiece: (Getty objects, 87.PA.27, 86.PA.740) Jacques-Louis David. Self-Portrait, 1794. Oil on canvas, 81 x 64 cm (31/8 x 25/4 in.). Paris, © 1997 The J. Paul Getty Museum Musee du Louvre (3705). © Photo R.M.N. 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, California 90265-5799 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs Mailing address: provided) courtesy of the owners, unless otherwise P.O. Box 2112 indicated. Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 Typography by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Library of Congress Austin, Texas Cataloging-in-Publication Data Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., Hong Kong Johnson, Dorothy. Jacques-Louis David, the Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis / Dorothy Johnson, p. cm.—(Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references (p. — ). ISBN 0-89236-236-7 i. David, Jacques Louis, 1748 — 1825. Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis. 2. David, Jacques Louis, 1748-1825 Criticism and interpretation. 3. Telemachus (Greek mythology)—Art. 4. Eucharis (Greek mythology)—Art. I. Title. -

All at Sea: Romanticism in Géricault's Raft of the Medusa

All at Sea: Romanticism in Géricault's Raft of the Medusa Galven Keng Yue Lee All at sea. We – receptacles, tentacles Of ingestion and Assemblage. A mass of ever-dying, ever-living Vapid waves. All at sea. ~ Galven Keng Yue Lee Plate 1: Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1819, oil on canvas, 491 x 716 cm. Source: Musée du Louvre, Paris. Fair use is claimed for not-for-profit educational & scholarship purposes. Abstract Théodore Géricault’s painting, Raft of the Medusa, has long been regarded as a quintessentially Romantic painting. Yet it was unprecedented when it was exhibited at the 1819 Salon by its raw and direct appeal to the viewer’s 1 The ANU Undergraduate Research Journal emotions, and represented an early stage in French Romantic painting. In this paper, I argue that the painting was an original, logical outcome of the social and political turbulence that plagued French society in the early nineteenth century and which also impinged itself on the personal circumstances of Géricault’s life. It is through this general malaise and sense of crisis that the painting can not only be seen as an authentic product of its time, but also one that reflected the distinctly personal nature of the Romantic painting, through the intense personal involvement and identification of Géricault with its creation and subsequent legacy. Romanticism in Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa is a stunning piece that strikes the viewer with its intense, emotional representations of hope and hopelessness. The pointless suffering of the denizens of the raft eradicate any pretensions to heroic achievement or tragic sacrifice; only the surging waves of the ocean respond without sympathy to their cries for salvation from a suffering which has only brought them to the pits of unheroic despair—drawing us within the vacant expression of the older man in the left foreground clutching onto the limp body of a younger male, possibly his son. -

The Raft of the Medusa the Story of a Painting, the Painting of a Story

The Raft of the Medusa The story of a painting, the painting of a story Scheme of Work Suitable for KS4 pupils Written and Designed by David Herbert Drama and Education Consultant [email protected] [Image of The Raft of the Medusa available at <www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/raft-medusa>] [For copyright reasons some visual images included in the original Resource Pack have been omitted here.] Contents Introduction..................................................................................p.3 Aims of the Scheme.....................................................................p.4 Tasks............................................................................................p.4 • The word “trapped” • Outline of story • Stages of Degeneration • Props • Lyrics to the song • News report Evaluation....................................................................................p.8 The Written Portfolio....................................................................p.9 Sources......................................................................................p.10 • The Raft of the Medusa story • Stages of Degeneration Portfolio Worksheets..................................................................p.13 • Drama Coursework – Stages of Degeneration • Storyboarding • Trapped evaluation Skills to allow students to explore in more depth.......................p.17 Reading List...............................................................................p.18 2 Introduction This scheme of work has been written and designed -

Wreck: Gericault and the Body in Pieces

Art Appreciation Lecture Series 2019 Being human: The figure in art Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa Mark Ledbury 12 / 13 June 2019 Lecture summary: This lecture examines one of the great works of nineteenth-century Art, Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, 200 years after the painting was first seen. It explores Gericault’s fascination with bodies, but also the political and cultural impact of a painting in its time and beyond. The wreck of the Medusa through incompetence and fear , the subsequent appalling suffering of the occupants of the Raft, caused scandal in the France of the recently restored Monarchy , and Gericault used both his fascination with human and animal bodies and his training in neo-classical studios to very powerful effect in a painting of enormous scale, ambition and effort. Slide list: 1. Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa, (Oil on canvas, 1817-19, 4,91 m. x 7,16 m, Paris: Louvre) 2. Horace Vernet, Portrait of Géricault, (Oil on Canvas, 1822 or 3, New York, Metropolitan Museum) 3. J-A-D Ingres, Grande Odalisque (1812-18, Oil on Canvas, Paris: Louvre) 4. A-L Girodet, Pygmalion (1818-19, Oil on Canvas, Paris: Louvre) 5. Achille Etna Michallon, The Death of Roland (oil on canvas, 1818, Paris: Louvre) 6. Géricault, Horse Studies,(Graphite on Paper, c.1812-14, Getty Museum, Los Angeles) 7. Géricault, Charging Chasseur, or An Officer of the Imperial Horse Guards Charging 1812, Oil on Canvas, Paris, Louvre 8. Géricault, Wounded Cuirassier leaving the Battle (1814, Oil on Canvas, Paris: Louvre) 9. -

A.P. Art History Simplified Timeline Through 1900 Note: These Are Approximate Dates

Marsha K. Russell 1 St. Andrew's Episcopal School, Austin, TX A.P. Art History Simplified Timeline through 1900 Note: These are approximate dates. Remember periods and styles overlap. Prehistory Paleolithic: up to about 10,000 BCE • Venus/Goddess of Willendorf • Lascaux Cave Paintings • Altamira Cave Paintings Neolithic in England: about 2,000 BCE • Stonehenge Mesopotamia/Near East (ignore time lapses) Sumerian: ~3500 - 2300 BCE • Standard of Ur • Ram offering stand • Bull-headed lyre • Bull holding a Vase • Ziggurats Akkadian: ~2300 - 2200 BCE • Victory Stele of Naram-Sin Neo Sumerian: ~2200 - 2000 BCE • Gudea statues Babylonian: ~1900 - 1600 BCE • Stele of Hammurabi Assyrian: ~900 - 600 BCE • Lamassu (Winged Human-Headed Bull) • Lion Hunt Bas Reliefs Egypt Predynastic: 3500 - 3000 BCE • Palette of Narmer Old Kingdom: ~3000 - 2200 BCE • Khafre • Menkaure and Khamerernebty • Seated Scribe • Ti Watching a Hippo Hunt • Prince Rahotep and his wife Nofret • Pyramid of King Djoser by Imhotep Middle Kingdom: ~2100 - 1600 BCE • Rock-cut tomb New Kingdom: ~1500 - 40 BCE (includes the Amarna Period 1355 – 1325 BCE) • Funerary Temple of Hatshepsut • Temple of Ramses II • Temple of Amen-Re at Karnak • Akhenaton • Akhenaton and His Family Marsha K. Russell 2 St. Andrew's Episcopal School, Austin, TX Aegean & Greece Minoan: ~2000 - 1500 BCE • Snake Goddess • Palace at Knossos • Dolphin Fresco • Toreador Fresco • Octopus Vase Mycenean: ~1500 - 1100 BCE • "Treasury of Atreus" with its corbelled vault • Repoussé masks • Lion Gate at Mycenae • Inlaid dagger -

Romanticism, Rebellion, and the Music of the Future an Essay By

Romanticism, Rebellion, and the Music of the Future An essay by Thomas Hampson and Carla Maria Verdino‐Süllwold From the liner notes of Berlioz, Wagner, and Liszt: Romantic Songs (EMI, 1994) “A cesspool of mud and filth!” was Richard Wagner’s first reaction to Paris when he arrived there after fleeing Riga in 1839. Yet, like countless musicians before him, the beleaguered composer had been drawn to the French capital with its diverse and stimulating cross‐section of artists, thinkers and prime movers. To some degree Wagner’s observations about mid‐19th‐century Paris were correct: the network of unpaved boulevards teemed with carriages, carts and pedestrians; sewage ran into the streets, and the scarcity of public baths made smells formidable. Yet Paris boasted Europe’s oldest university, arguably its finest cuisine, and a rich array of spectacle and serious entertainment for its citizenry. It was gas illumination in 1829 that gave the metropolis its nickname “City of Light,” but it was the radiance of its artistic and intellectual climate that made the appellation endure. 19th‐century Paris was the center of modern science, historical scholarship, philosophical, social, political and religious theory, as well as the cradle of literary, artistic and musical innovation. As the birthplace of 18th‐century revolution, she bequeathed a legacy of violent political and cultural change to the subsequent era. The collapse of Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité into the bloodbath of the Reign of Terror resulted in the rise of Napoleon, at first hailed by the Romantics as a symbol of energy and transforming power, only to be mourned, as Beethoven did in the lugubrious chords of the Eroica, as the heroic ideal manqué. -

Le Modèle Noir De Géricault À Matisse

Adrienne L. Childs exhibition review of Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019) Citation: Adrienne L. Childs, exhibition review of “Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw. 2019.18.2.18. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Childs: Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019) Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse Musée D’Orsay, Paris March 26–July 21, 2019 ACTe Memorial, Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe September 13–December 19, 2019 Catalogue: Le Modèle noir de Gericault à Matisse. Paris: Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie and Flammarion, 2019. 384 pp.; 274 color illus.; bibliography; index. $47 (hardcover) ISBN: 978-2-35433-281-5 ISBN: 978-2-0814-8096-4 In the heat of the racially charged American political climate of the 1960s, the French- American collectors and patrons Jean and Dominique de Menil embarked on The Image of the Black in Western Art project, a monumental effort to document all of the images of blacks in Western art. The de Menils believed that dignified, beautiful representations of black men, women, and children emanating from the ancient Mediterranean to modern Europe would serve as a counternarrative to the toxic atmosphere of race relations they witnessed while living in the United States. -

Exemplar for Internal Achievement Standard Art History Level 2

Exemplar for internal assessment resource Art History for Achievement Standard 91184 Exemplar for Internal Achievement Standard Art History Level 2 This exemplar supports assessment against: Achievement Standard 91184 Communicate an understanding of an art history topic An annotated exemplar is an extract of student evidence, with a commentary, to explain key aspects of the standard. It assists teachers to make assessment judgements at the grade boundaries. New Zealand Qualifications Authority To support internal assessment © NZQA 2014 Exemplar for internal assessment resource Art History for Achievement Standard 91184 Grade Boundary: Low Excellence 1. For Excellence, the student needs to communicate perceptive understanding of an art history topic. This involves: • evaluating key ideas to drawing insightful conclusions based on information gathered • using supporting evidence gathered from art works and other sources This student has investigated Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat and Théodore Gericault’s The Raft of Medusa. Evidence of perceptive understanding is apparent in the insightful conclusions drawn from the evaluation of The Death of Marat (1), and the evaluation of the concerns of Romanticism and Neoclassicism (2). These have been supported by evidence from art works (3) and evidence from other sources (4). Insight is also apparent in the final conclusions, which draw on the preceding evaluations of David and Gericault (5). For a more secure Excellence, the student could include more detail in their evaluative discussion of key ideas, and integrate relevant supporting evidence into their final conclusion. © NZQA 2014 David saw Marat’s death as an opportunity for political propaganda and a way to demand political action. -

Chapter 21 New Directions in Nineteenth-Century Art 467 David’S Work Gives You Only One Side of the Story, However

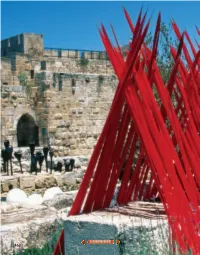

462 7 Art of the Modern Era t the beginning of the nineteenth century, A the elegant, lighthearted Rococo style lost favor with artists who adopted new styles, including Neoclassicism and Romanticism. Artists responded to the new freedoms developing during this era by experimenting with new ways to express their ideas and feelings. In this unit, you will discover works such as the one shown here, by glass artist David Chihuly. His installa- tion In the Light of Jerusalem, includes spectacu- lar colored glass sculpture displayed at the Tower of David Museum in Jerusalem. Web Museum Tour Discover more innovative glasswork by Chihuly in the Mint Museum’s contemporary collection. Visit the museum galleries and tour the Mint’s Museum of Craft and Design. Click on Web Museum Tours at art.glencoe.com. Activity Choose between the Mint Museum of Art or the Museum of Craft and Design. Scroll through the thumbnails to view the collections. Note the variety of media represented in the artworks. What other types of glass artworks can you find at the museum site? Dale Chihuly. Red Spears. 1999. Glass installation. Jerusalem. 463 21 New Directions in Nineteenth-Century Art ave you ever taken an art lesson or attended an art school? Do stu- H dents learn from each other as well as from the teacher? The acade- mies, or art schools, in France and England during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries urged their students to study the works of the past as a way of developing their own skills. This inspired an artistic style called Neo- classicism, which replaced the Rococo style. -

The Raft of the Medusa an Analysis of Géricault’S Portrayal of Race, Politics and Class

The Raft of the Medusa An Analysis of Géricault’s Portrayal of Race, Politics and Class March 15th, 2004 – HIS367 – History of Images – 991502502– P. Rutherford Jake Hirsch-Allen 1 The Thematic Approach ~ Few paintings have provoked as varied and enduring a response as Theodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa. The debate surrounding this piece is perhaps best analyzed thematically in terms of race and immigration, artistic style and breakthroughs, realism and regime. While a thorough exploration of any one of these topics would require a novel and in fact, many have been written about the painting (each a testament to the depth of meaning latent in it), a cursory discussion of several of these issues illuminates the significance of the piece within historical and contemporary discussions of class, and, more generally, within art history. The Shipwreck of the Medusa ~ For his contemporaries, Géricault’s painting represented one scene of the terrible story of a shipwreck caused by an inept captain appointed through the favouratism of the Bourbon monarchy: The Medusa had outrun its convoy on its way to Senegal to reinstate French colonial interests, there when Captain Duroys de Chaumareys ran the ship aground. With lifeboats for only two hundred and fifty of the four hundred passengers on board, the remaining soldiers, sailors, officers and civilians were forced onto a makeshift raft. The captain, aristocrats, officers and their families, who occupied the lifeboats, after agreeing to tow the raft, promptly severed the ropes attaching it to their boats, abandoning its occupants to the elements without provisions. Many died the first night, July 5th, 1816. -

Orientalism and the Photographs of Delacroix

Orientalism and the Photographs of Eugène Delacroix: An Exploration of Vision, Identity, and Difference in Nineteenth Century France A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Elizabeth J. DeVito June 2011 © 2011 Elizabeth J. DeVito. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Orientalism and the Photographs of Eugène Delacroix: An Exploration of Vision, Identity, and Difference in Nineteenth Century France by ELIZABETH J. DEVITO has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Jaleh Mansoor Assistant Professor of Art History Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT DEVITO, ELIZABETH J., M.A., June 2011, Art History Orientalism and the Photographs of Eugène Delacroix: An Exploration of Vision, Identity, and Difference in Nineteenth Century France Director of Thesis: Jaleh Mansoor This thesis investigates some of the experimental Orientalist photographs of Eugène Delacroix from 1854. I explore these works through a post-colonial, feminist, and Lacanian psychoanalytical perspective, in order to understand how these unusual photographs operate in nineteenth century, bourgeois France. The first chapter discusses the images of Delacroix, who is canonized as a painter, as they both create and are produced by a newly emergent Spectacle culture supported by the rapidly proliferating, fairly young, medium of photography. The second chapter recognizes the bodies of the nude female figures as sites of imperialist and misogynistic ideologies to develop, which in turn justifies colonial enterprises in the Near East. The final chapter seeks to explore the materiality of the photograph, or more specifically, the nude female image, seen as both Romantically traditional and erotic via the gaze.