Carving up the World at Its Political Joints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Analysis

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FINAL BILL ANALYSIS BILL #: HB 1013 FINAL HOUSE FLOOR ACTION: SUBJECT/SHORT Daylight Saving Time 103 Y’s 11 N’s TITLE SPONSOR(S): Nuñez; Fitzenhagen and others GOVERNOR’S Approved ACTION: COMPANION CS/CS/SB 858 BILLS: SUMMARY ANALYSIS HB 1013 passed the House on February 14, 2018, and subsequently passed the Senate on March 6, 2018. The bill declares the Legislature’s intent to observe Daylight Saving Time year-round throughout the entire state if federal law is amended to permit states to take such action. The bill does not appear to have a fiscal impact. The bill was approved by the Governor on March 23, 2018, ch. 2018-99, L.O.F., and will become effective on July 1, 2018. This document does not reflect the intent or official position of the bill sponsor or House of Representatives. STORAGE NAME: h1013z1.LFV.docx DATE: March 28, 2018 I. SUBSTANTIVE INFORMATION A. EFFECT OF CHANGES: Present Situation The Standard Time Act of 1918 In 1918, the United States enacted the Standard Time Act, which adopted a national standard measure of time, created five standard time zones across the continental U.S., and instituted Daylight Saving Time (DST) nationwide as a war effort during World War I.1 DST advanced standard time by one hour from the last Sunday in March to the last Sunday in October.2 DST was repealed after the war but the standard time provisions remained in place.3 During World War II, a national DST standard was revived and extended year-round from 1942 to 1945.4 Uniform Time Act of 1966 Following World War -

Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2002

Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2002 Edited by Clive Wilkinson PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Dedication This book is dedicated to all those people who are working to conserve the coral reefs of the world – we thank them for their efforts. It is also dedicated to the International Coral Reef Initiative and partners, one of which is the Government of the United States of America operating through the US Coral Reef Task Force. Of particular mention is the support to the GCRMN from the US Department of State and the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. I wish to make a special dedication to Robert (Bob) E. Johannes (1936-2002) who has spent over 40 years working on coral reefs, especially linking the scientists who research and monitor reefs with the millions of people who live on and beside these resources and often depend for their lives from them. Bob had a rare gift of understanding both sides and advocated a partnership of traditional and modern management for reef conservation. We will miss you Bob! Front cover: Vanuatu - burning of branching Acropora corals in a coral rock oven to make lime for chewing betel nut (photo by Terry Done, AIMS, see page 190). Back cover: Great Barrier Reef - diver measuring large crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) and freshly eaten Acropora corals (photo by Peter Moran, AIMS). This report has been produced for the sole use of the party who requested it. The application or use of this report and of any data or information (including results of experiments, conclusions, and recommendations) contained within it shall be at the sole risk and responsibility of that party. -

Mitchell 1936 R.Pdf

RULES ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HANAll NAY 21 i 9 4 8. NITH REGARD TO THE REPRODUCTION OF MASTERS THESES la » No person or corporation may publish or reproduce in any manner, without the consent of the Board of Regents, a thesis which has been submitted to the University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree. ibJ No individual or corporation or other organization may publish quotations or excerpts from a graduate thesis without the consent of the author and of .the University. EDUCATION IN AMERICAN SAMOA it WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO HEALTH PROBLEMS by DONALD DEAN MITCHELL A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Division of the University of Hawaii In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts June 1936 Approved by / . 1 / ' /(Chairman) if? no.1^5 CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE 3&-&T 1 Samoa and the Samoans 1 II The Changing Samoa-— --------- -------------16 III Education In American Samoa— — ------ 55 IV Health Education in American Samoa--------- -87 Appendix------- 192 Bibliography--- — -— — --- — ------------200 Kam Kam Bindery 4 8 9 4 1 JUL 1 3 1936 ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE FIGURE 1. MAP OF THE ISLANDS OF AMERICAN SAMOA......... v. FIGURE 2. CHART SHOWING THE ADMINISTRATIVE ORGANI ZATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, AMERICAN SAMOA.............................. 82 FIGURE 3. CHART SHOWING THE ORGANIZATION OF THE PUBLIC HEALTH DEPARTMENT OF AMERICAN SAMOA........ 108 TABLES TABLE I. POPULATION STATISTICS................... 192 TABLE II. MORTALITY STATISTICS................... 193 TABLE HI. CAUSES OF DEATHS IN AMERICAN SAMOA FOR THE YEAR 1934...................... 194 TABLE IV. DEATHS ACCORDING TO SEX AND QUINQUENNIAL AGE GROUPS............................ -

Time Zone Boundaries V2016.10 Updates

Time Zone Changes applied to October 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ Many areas of Russia have changed the name of their time zone to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). Cyprus ▪ On October 30, 2016, when Europe and the rest of Cyprus will set their clocks back 1 hour to UTC+2, Northern Cyprus will remain on UTC+3. 1 Time Zone Changes applied to April 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ Magdan Oblast will forward 1 hour April 24, 2016. Venezuela ▪ On May 1, Venezuelans will set their clocks forward 30 minutes. Azerbaijan ▪ Azerbaijan has cancelled Daylight Saving Time (DST) and will not move the clocks forward on March 27, 2016. 2 Time Zone Changes applied to March 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ President Putin signed four bills into law, making changes to the following time zone regions: Sakhalin Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Altai Republic and Altai Krai. The result of these changes modify/create the time zone regions of Transbaikal (Zabaykalsky Krai), Astrakhan Oblast, Sakhalin Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Altai Republic, and Altai Krai. Chile ▪ Chile will resume seasonal clock changes in 2016 after spending all of last year on Daylight Saving Time (DST). The South American country will turn clocks back by one hour in May. Brazil ▪ Residents Clocks in southern Brazilian states will be turned back by 1 hour at midnight between Saturday, February 20 and Sunday, February 21, 2016, as Daylight Saving Time (DST) ends. Haiti ▪ Haiti will not observe Daylight Saving Time (DST) in 2016. The planned clock change on Sunday, March 13, 2016 has just been canceled. United States ▪ Metlakatla, Alaska will observe the same local time as the rest of the state from now on. -

Standard Time Zones of the World Map (PDF)

STANDARD TIME ZONES OF THE WORLD 165 150 135 120 105 90 75 60 45 30 15 03015 45 60 75 90 105 120 135 150 165 180 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 12 11 A R C T I C O C E A N Svalbard A R C T I C O C E A N (NORWAY) SEVERNAYA ZEMLYA FRANZ JOSEF Qaanaaq LAND (Thule) Kara Sea 6 0 Greenland Sea 4 Laptev Sea NEW SIBERIAN ISLANDS Greenland 75 3 75 (DENMARK) Barents Sea NOVAYA Baffin East Siberian Sea 1 ZEMLYA Beaufort Sea Bay 3 Wrangel Itseqqortoomiit Jan Mayen Island 7 (Scoresbysund) (NORWAY) Chukchi 5 Norwegian Sea Sea Repulse Bay U.S. 11 Iqaluit Davis ICELAND 12 Dawson 6 Denmark 0 9 (Frobisher Bay) Strait Strait 9 Nuuk (Godthåb) SWEDEN FINLAND R U S S I A Yakutsk Anchorage 10 9 NORWAY St. Petersburg 5 7 Magadan 60 Hudson 60 EST. Bay 3 4 Perm' Izhevsk Bering Sea C A N A D A Labrador LAT. 8 North DENMARK Moscow Omsk UNITED LITH. Novosibirsk Edmonton Sea Sea RUS. Lake Baikal Sea IRELAND BELARUS 4 4 KINGDOM Samara of Petropavlovsk- U.S. 10 NETH. POLAND Astana GERMANY Okhotsk Kamchatskiy AL Island of London EUT N D S Newfoundland BEL. Sakhalin I AN I S L A Winnipeg LUX. S CZ. REP. D UKRAINE N Paris SLOV. 6 LA 3½ KAZAKHSTAN IS AUS. MOLDOVA L Québec 10 RI SWITZ. HUNG. Aral U FRANCE SLO. -

International Date Line Act 2011

SAMOA INTERNATIONAL DATE LINE ACT 2011 Arrangement of Provisions 1. Short title and 7. Calculation of interest commencement 8. Effect on pay and allowances 2. Act binds the Government 9. Offence and penalty 3. Interpretation 10. Maps, charts and atlases 4. Samoa standard time 11. Non-liability of Government 5. International Date Line 12. Consequential amendments 6. Deeming provisions Schedule INTERNATIONAL DATE LINE ACT 2011 No. 6 AN ACT to provide for the change to standard time in Samoa and to make consequential amendments to the position of the International Date Line, and for related purposes. [Assent date:28 June 2011] [Commencement date for whole Act: 29 December 2011] Commencement for section 5(3): 28 June 2011] BE IT ENACTED by the Legislative Assembly of Samoa in Parliament assembled as follows: 1. Short title and commencement – (1) This Act may be cited as the International Date Line Act 2011. (2) Except for section 5(3), this Act commences at 12 o’clock midnight, on Thursday 29 December 2011. (3) Section 5(3) commences on the date of assent by the Head of State. 2 International Date Line Act 2011 2. Act binds the Government – This Act binds the Government of Samoa. 3. Interpretation – In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires: “instrument” includes: (a) a form of enactment, order, notice or rule made under delegated power conferred by statute or regulation; and (b) a contract taking effect in Samoa or having affecting parties in Samoa regardless of where the contract is to be performed or enforced; “International Date Line” means meridian (in red colour) depicted in the map in the Schedule; “Samoa standard time” in this Act and any other statute of Samoa which refers to ‘Samoa standard time’ means the time 13 hours in advance of Co-ordinated Universal Time. -

What Every Developer Should Know About Time 1807: the Noon Gun Starts firing a Time Signal in Cape Town, South Africa [Bis79]

1 What every developer should know about time 1807: The Noon Gun starts firing a time signal in Cape Town, South Africa [Bis79]. This allows ships in the port to check the accuracy of their marine chronometers. Marine chronometers Martin Thoma are used on ships to help calculate the longitude. E-Mail: [email protected] 1825: The Stockton and Darlington Railway opened [Tom15]. This raised the need for synchronized times for train schedules Abstract—This paper introduces basic concepts around time, started to rise. Often, the time of a big city like Berlin was including calendar systems, time zones, UTC and offsets. It gives chosen. This was then called Berlin Standard Time. a brief historic overview of systems that are applied to simplify the understanding. 1838: Telegraphy made time synchronization possible [TM99]. 1876: After missing a train, Sir Sandford Fleming proposes I. INTRODUCTION to use a 24-hour clock. So instead of distinguishing 6am and 6pm, he proposes to distinguish 6 o’clock and 18 o’clock. Time is such a fundamental concept that we rarely think about 1884: Sir Sandford Fleming proposed a worldwide standard it in detail. When one is forced to develop software or analyzes time at the International Meridian Conference to which 24 time data generated by software, one needs to understand the edge ◦ zones of 360 = 15◦ latitude are added as local offsets. This cases. This paper is a short introduction to those concepts and 24 way, the local time at each place would be at most half an edge cases. The paper is inspired by [Sus12a], [Sus12b] and hour off from the standardized time and simplify the system John Skeet’s talk at NDC London in January 2017. -

Tides Around the World!

Tides Around the World! A day of tides, worldwide Tides are caused by gravitational interactions between the Earth, Sun, and Moon. Both the Sun and Moon influence tides on Earth and result in “bulges” in Earth’s oceans that changes depending on the orientation of the Sun and Moon (see figure 1). Since the Moon revolves around the Earth, this orientation changes over the course of the month, causing larger or small tidal bulges. Meanwhile, the Earth is also rotating on its axis, once every 24 hours. Let’s see if we can identify and make sense of patterns in tidal data for different locations around the Earth. Figure 1. Schematic diagram of (exaggerated) tidal bulges created by the Moon. A note on timekeeping and time zones When we say, “It’s twelve o’clock noon,” we are probably referring to local time. Local time is probably most useful to us in our daily lives: maybe we get up at 6 o’clock in the morning, eat lunch at 11:30, get out of school at 3 o’clock or 4 o’clock in the afternoon, and go to bed by nine in the evening. If you’ve ever traveled far enough east or west from your home, maybe you’ve entered a different time zone. In different time zones, we shift “local time” so that it makes sense for that place on the planet. If we didn’t have different time zones, then “twelve o’clock noon” at one place on the Earth would be light outside, while on the other side of the Earth it would be pitch dark! Instead, we shift the time so that “twelve o’clock noon” means approximately the same thing everywhere on the planet. -

Development Policy Sovereignty in Samoa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Pule: Development policy sovereignty in Samoa Avataeao Junior Ulu 2013 A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Development Studies School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Glossary ............................................................................................................................................................ 7 List of Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................. 9 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 11 Overall aim: ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Research questions: ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Thesis structure ............................................................................................................................................ -

The Pulenu'u in Samoa the Transformation of An

THE PULENU'U IN SAMOA THE TRANSFORMATION OF AN OFFICE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES MAY 2006 By Kevin Riddle Thesis Committee: Terence Wesley-Smith, Chairperson John F. Mayer David Chappell David Hanlon We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree ofMaster ofArts in Pacific Islands Studies. Thesis Committee Chairperson 11 Dedicated to my parents, Jon and Nancy 111 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Unbeknownst to myself, work on this thesis began when I first arrived in Samoa in 2001. That experience changed the course ofmy life in an undoubtedly positive way and I am grateful to all the individuals who supported me throughout my time in Samoa. lowe much to my Peace Corps friends for their unwavering support and alofa; Amelia, Lili, Hilo, Taui, Sefo, Anne, Sita, Sone, Cat, Ina, Pati and Serna. I would like to thank the 'aiga ofLolo Fatu ofMatatufu for opening their house to me and helping me to become familiar with and appreciate the fa'aSamoa. In addition, lowe a great deal to MaIolo Olomaga Sese and Fasina MaIolo for welcoming me into their family for two years. In addition, I am indebted to my host brothers Malua and Junior for helping me integrate into the village of Vaisala. I would also like to thank Aumua Kiso and his family for their hard work and allowing me to leave the Peace Corps with a sense ofaccomplishment. -

Aspects of Samoan Women's Wartime Experiences

SUBTLE INVASIONS: ASPECTS OF SAMOAN WOMEN’S WARTIME EXPERIENCES SAUI’A LOUISE MARIE TUIMANUOLO MATAIA-MILO A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE VICTORIA UNIVERSITY OF WELLINGTON IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY VICTORIA UNIVERSITY OF WELLINGTON 2017 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks and gratitude to my supervisors, Adrian Muckle, and Charlotte Macdonald for all your assistance. I thank you most sincerely for your patience, interest, and immense knowledge that guided and helped me through this research. I could not have imagined having better advisors and mentors for this journey. I acknowledge the scholarship award under the Memorandum of Understanding between the National University of Samoa and Victoria University that enabled me to pursue this study. I also received financial assistance from the Victoria Doctoral Hardship Scholarship and Victoria Doctoral Submission Scholarship. I would also like to express my deepest appreciation to all my research participants (age 83-105 years), in Upolu, Manono, Savai’i, Tutuila and Manu’a, and in Auckland. You graciously agreed to be interviewed, to contribute and to share your wartime life stories. You are the reason I set out to find answers. Your war experiences have become the core of this thesis. Without you this study would not have been possible. I know most of you have passed on to the spirit world, but your wisdom will strengthen the next generation of Samoan women. A number of people have contributed their services to improve the quality of this thesis, notably the VUW Librarians Justin Cargill and Tony Quinn, the staff of the New Zealand National Library/Alexander Turnbull Library and Archives New Zealand. -

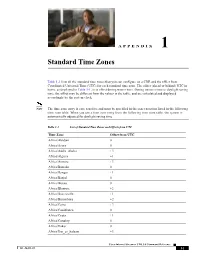

Appendix 1, “Standard Time Zones”

APPENDIX 1 Standard Time Zones Table 1-1 lists all the standard time zones that you can configure on a CDE and the offset from Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) for each standard time zone. The offset (ahead or behind) UTC in hours, as displayed in Table 1-1, is in effect during winter time. During summer time or daylight saving time, the offset may be different from the values in the table, and are calculated and displayed accordingly by the system clock. Note The time zone entry is case sensitive and must be specified in the exact notation listed in the following time zone table. When you use a time zone entry from the following time zone table, the system is automatically adjusted for daylight saving time. Table 1-1 List of Standard Time Zones and Offsets from UTC Time Zone Offset from UTC Africa/Abidjan 0 Africa/Accra 0 Africa/Addis_Ababa +3 Africa/Algiers +1 Africa/Asmera +3 Africa/Bamako 0 Africa/Bangui +1 Africa/Banjul 0 Africa/Bissau 0 Africa/Blantyre +2 Africa/Brazzaville +1 Africa/Bujumbura +2 Africa/Cairo +2 Africa/Casablanca 0 Africa/Ceuta +1 Africa/Conakry 0 Africa/Dakar 0 Africa/Dar_es_Salaam +3 Cisco Internet Streamer CDS 3.0 Command Reference OL-26431-01 1-1 Appendix 1 Standard Time Zones Table 1-1 List of Standard Time Zones and Offsets from UTC (continued) Time Zone Offset from UTC Africa/Djibouti +3 Africa/Douala +3 Africa/El_Aaiun +1 Africa/Freetown 0 Africa/Gaborone +2 Africa/Harare +2 Africa/Johannesburg +2 Africa/Kampala +3 Africa/Khartoum +3 Africa/Kigali +2 Africa/Kinshasa +1 Africa/Lagos +1 Africa/Libreville +1