Images of Masculinity: Ideology and Narrative Structure in Realistic Novels for Young Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Children's Book Council of Australia Book of the Year Awards

THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — CONTENTS Page BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — 1981 . 2 BOOK OF THE YEAR: OLDER READERS . .. 7 BOOK OF THE YEAR: YOUNGER READERS . 12 VISUAL ARTS BOARD AWARDS 1974 – 1976 . 17 BEST ILLUSTRATED BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 17 BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD: EARLY CHILDHOOD . 17 PICTURE BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 20 THE EVE POWNALL AWARD FOR INFORMATION BOOKS . 28 THE CRICHTON AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 32 CBCA AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 33 CBCA BOOK WEEK SLOGANS . 34 This publication © Copyright The Children’s Book Council of Australia 2021. www.cbca.org.au Reproduction of information contained in this publication is permitted for education purposes. Edited and typeset by Margaret Hamilton AM. CBCA Book of the Year Awards 1946 - 1 THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 – From 1946 to 1958 the Book of the Year Awards were judged and presented by the Children’s Book Council of New South Wales. In 1959 when the Children’s Book Councils in the various States drew up the Constitution for the CBC of Australia, the judging of this Annual Award became a Federal matter. From 1960 both the Book of the Year and the Picture Book of the Year were judged by the same panel. BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD 1946 - 1981 Note: Until 1982 there was no division between Older and Younger Readers. 1946 – WINNER REES, Leslie Karrawingi the Emu John Sands Illus. Walter Cunningham COMMENDED No Award 1947 No Award, but judges nominated certain books as ‘the best in their respective sections’ For Very Young Children: MASON, Olive Quippy Illus. -

The Text Publishing Company Bologna Rights List 2018

The Text Publishing Company Bologna Rights List 2018 Recent Acquisitions ......................................................................................................... 2 Recent Publications ......................................................................................................... 3 The Huggabie Falls Series by Adam Cece ..................................................................... 4 The Peacock Detectives by Carly Nugent ......................................................................... 5 The Art of Taxidermy by Sharon Kernot .......................................................................... 6 Bonesland by Brendan Lawley ......................................................................................... 7 The Finder by Kate Hendrick ............................................................................................ 8 The Boy from Earth by Darrell Pitt ................................................................................... 9 Text Classics .............................................................................................................. 10–12 Various titles by Robin Klein ......................................................................................... 11 Various titles by Ivan Southall ...................................................................................... 12 Text Publishing Agents .......................................................................................... 13–14 For additional information, please contact: Penny Hueston -

39-40.Pdf (334.4Kb)

LITERARY CRITICISM of Longtime, and the magical worlds of Peg Maltby. The A Formidable History depth and breadth of Saxby’s knowledge allow for revealing links between eras, authors, titles, themes, approaches and characters. For example, he says of the fates of two characters Pam Macintyre created thirty-six years apart — Raylene in Brinsmead’s Beat of the City (1966) and Louise in Sonya Hartnett’s Maurice Saxby All My Dangerous Friends (1998), which treats a similar subject — ‘But [Raylene] was created in the sixties when Images of Australia: A History of Australian closure was more important than truth’, revealing much about Children’s Literature 1941–1970 the respective eras. Scholastic, $59pb, 848pp, 1 865 04456 3 The rôle of school and public libraries, the Children’s Book Council, educational practices, visionary personalities LTHOUGH HE ATTRIBUTES it to Walter McVitty’s such as Marjorie Cotton (do I detect a New South Wales Innocence and Experience (1981) and Brenda Niall’s bias?), publishers and editors, children’s bookshops, special- A Australia through the Looking Glass (1984), there ist collections, reviewing journals, and non-fiction and educa- is no doubt that Maurice Saxby’s pioneering A History of tional publishing are carefully acknowledged and weighted. Australian Children’s Literature (1969, 1971), along with More than 800 pages permit leisurely explorations of Marcie Muir’s Bibliography of Australian Children’s Books books, authors and genres, and the inclusion of carefully (1970, 1976), established the canon of Australian children’s chosen textual excerpts that resonate with contemporary literature. Images of Australia, along with his The Proof attitudes, venues and language. -

Story Time: Australian Children's Literature

Story Time: Australian Children’s Literature The National Library of Australia in association with the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature 22 August 2019–09 February 2020 Exhibition Checklist Australia’s First Children’s Book Charlotte Waring Atkinson (Charlotte Barton) (1797–1867) A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales Sydney: George Evans, Bookseller, 1841 Parliament Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn777812 Charlotte Waring Atkinson (Charlotte Barton) (1797–1867) A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales Sydney: George Evans, Bookseller, 1841 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn777812 Living Knowledge Nora Heysen (1911–2003) Bohrah the Kangaroo 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn1453161 Nora Heysen (1911–2003) Dinewan the Emu 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn1458954 Nora Heysen (1911–2003) They Saw It Being Lifted from the Earth 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn2980282 1 Catherine Stow (K. ‘Katie’ Langloh Parker) (author, 1856–1940) Tommy McRae (illustrator, c.1835–1901) Australian Legendary Tales: Folk-lore of the Noongahburrahs as Told to the Piccaninnies London: David Nutt; Melbourne: Melville, Mullen and Slade, 1896 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn995076 Catherine Stow (K. ‘Katie’ Langloh Parker) (author, 1856–1940) Henrietta Drake-Brockman (selector and editor, 1901–1968) Elizabeth Durack (illustrator, 1915–2000) Australian Legendary Tales Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1953 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn2167373 Catherine Stow (K. -

Frances A. TITLE 'Good Reaaing from and About Australiafor 10-15 Year Olds: PUB DATE 82 K NOTE 12P.F Contains Kight Print Type

DOCUleNTRESUME ,ED 229 298 SO 014 611 AUTHOR Miller,'Frances A. TITLE 'Good Reaaing from and about Australiafor 10-15 Year Olds: PUB DATE 82 k NOTE 12p.f Contains kight print type. AVAILABLE TROMFrances A. Miller, 24 Fairfax Road, Bellevue Hill, N.S.W. 2023, Australia ($1.00,5 or'mo:re, $0.75). .PUB TYPE Reference Materials'- Bibliographiei (131) ° EDRS PRICE MF01/*01 Plus-Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens.Literature; *Cultural-Awareness; Cultural Background;Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Nonfict.ion; *Novels; *Short Stories IDENTIFIERS . *Australia ABSTRACT Approximately 100 novels and other fictionalworks featuring Australian settings and themesare cited in this annotated bibliography. Appropriate forages 10-15, the books were chosen for a. non-Australian reading audience interested inlearning more about the country. Books are listed under the following topics:Australia*in the beginning,.vonvict colony, discovery ofgold, the new century (1900-1950), outback 'setiings, country settings,city/town settings, humorous tall tales, fantasy and childhood,and short story - collections. Five nonfiction booksare also cited. Each entry lists author, title, publisher, age level, and includesa brief synopsis. A glossary of Australian terms is included. (KC) *********************************************************************** .* Reproductions supplied_In EDRSare the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ************************************************************t*********, U.S. DEPARTMENT -

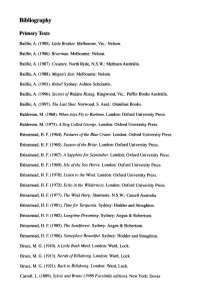

Bibliography Primary Texts

Bibliography Primary Texts Baillie, A. (1985). Little Brother. Melbourne, Vic: Nelson. Baillie, A. (1986). Riverman. Melbourne: Nelson. Baillie, A. (1987). Creature. North Ryde, N.S.W.: Methuen Australia. Baillie, A. (1988). Megan's Star. Melbourne: Nelson. Baillie, A. (1993). Rebel! Sydney: Ashton Scholastic. Baillie, A. (1996). Secrets ofWalden Rising. Ringwood, Vic: Puffin Books Australia. Baillie, A. (1997). The Last Shot. Norwood, S. Aust: Omnibus Books. Balderson, M. (1968). When Jays Fly to Barbmo. London: Oxford University Press. Balderson, M. (1975). A Dog Called George. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1964). Pastures of the Blue Crane. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1965). Season of the Briar. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1967). A Sapphire for September. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1969). Isle of the Sea Horse. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1970). Listen to the Wind. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1972). Echo in the Wilderness. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1977). The Wind Harp. Stanmore, N.S.W.: Cassell Australia. Brinsmead, H. F. (1981). Time for Tarquinia. Sydney: Hodder and Stoughton. Brinsmead, H. F. (1982). Longtime Dreaming. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Brinsmead, H. F. (1985). The Sandforest. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Brinsmead, H. F. (1986). Someplace Beautiful. Sydney: Hodder and Stoughton. Bruce, M. G. (1910). A Little Bush Maid. London: Ward, Lock. Bruce, M. G. (1913). Norah ofBillabong. London: Ward, Lock. Bruce, M. G. (1921). Back to Billabong. London: Ward, Lock. Carroll, L. (1889). Sylvie and Bruno (1988 Facsimile edition). New York: Dover Publications, Inc. Chauncy, N. -

Australia and Its German-Speaking Readers: a Study of How German Publishers Have Imagined Their Readers of Australian Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australia and Its German-Speaking Readers: A Study of How German Publishers Have Imagined Their Readers of Australian Literature OLIVER HAAG Austrian Research Centre for Transcultural Studies, Vienna APPENDIX Table 1: German Translations of Australian Fiction, 1821-present. This table is based on original research and serves as a basis for the findings conveyed in the present article as well as for more general overview and future research. 1 JASAL 2010 Special Issue: Common Readers Haag: Australia and Its German-Speaking Readers (Appendix) Year Author German Title Original Cover Blurb Illustration 1821 James Hardy Hardy Vauxs eines zweimal Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux Australia-specific Nil Vaux nach Botany Bay Verbannten (1819) Denkwürdigkeiten seines Lebens 1845 Charles Abenteuer eines Tales of the Colonies (1842- Australia-specific Nil Rowcroft Auswanderers [3 vols] 1843) 1846 Charles Abenteuer eines Tales of the Colonies (1842- Australia-specific Nil Rowcroft Auswanderers in den 1843) Colonien von Vandiemens- land [2 vols in 1] 1856 William Howitt Abenteuer in den Wildnissen Herbert’s Note-Book (1854) Australia-specific Nil von Australien 1857 William Howitt Australischer Robinson A Boy’s Adventures in the Wilds Australia-specific Nil of Australia (1854) 1865 Celeste de Die Sappho La Sapho (1958) Neutral Nil Chabrillan 1877 Clarke Deportirt auf Lebenszeit For the Term of His Natural -

Ideology and Narrative Structure in Realistic Novels for Young Adults

Images of masculinity: ideology and narrative structure in realistic novels for young adults A dissertation submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, September 2005 Lisbeth Clemens Graduate School of Library and Information Studies McGill University, Montreal ©Lisbeth Clemens 2005 Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-21635-4 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-21635-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell th es es le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Peters Township School District MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR READING LEVEL POINTS I Had A Hammer: Hank Aaron... Aaron, Hank 7.1 34 Postcard, The Abbott, Tony 3.5 17 My Thirteenth Winter: A Memoir Abeel, Samantha 7.1 13 Go And Come Back Abelove, Joan 5.2 10 Saying It Out Loud Abelove, Joan 5.8 8 Behind The Curtain Abrahams, Peter 3.5 16 Down The Rabbit Hole Abrahams, Peter 5.8 16 Into The Dark Abrahams, Peter 3.7 15 Reality Check Abrahams, Peter 5.3 17 Up All Night Abrahams, Peter 4.7 10 Defining Dulcie Acampora, Paul 3.5 9 Dirk Gently's Holistic... Adams, Douglas 7.8 18 Guía-autoestopista galá.... Adams, Douglas 8.1 12 Hitchhiker's Guide To The... Adams, Douglas 8.3 13 Life, The Universe, And... Adams, Douglas 8.6 13 Mostly Harmless Adams, Douglas 8.5 14 Restaurant At The End-Universe Adams, Douglas 8.1 12 So Long, And Thanks For All Adams, Douglas 9.4 12 Watership Down Adams, Richard 7.4 30 Storm Without Rain, A Adkins, Jan 5.6 8 Thomas Edison (DK Biography) Adkins, Jan 9.4 8 Ghost Brother Adler, C. S. 6.5 7 Her Blue Straw Hat Adler, C. S. 5.5 9 If You Need Me Adler, C. S. 6.9 7 In Our House Scott Is My... Adler, C. S. 7.2 8 Kiss The Clown Adler, C. S. 6.1 8 Lump In The Middle, The Adler, C. S. 6.5 10 More Than A Horse Adler, C. -

Reading Counts

Title Author Reading Level Sorted Alphabetically by Title 13 James Howe 4 47 Walter Mosley 5.2 1632 Eric Flint 8.1 1776 David McCullough 12.5 1984 George Orwell 8.2 2095 Jon Scieszka 5.4 29-Jun-99 David Wiesner 5.3 11-Sep-01 Andrew Santella 5.5 "A" Is for Abigail Lynne Cheney 4.6 $1.00 Word Riddle Book, The Marilyn Burns 6.5 1,2,3 In The Box Ellen Tarlow 1.2 10 Best Things… Dad Christine Loomis 1.6 10 Fat Turkeys Tony Johnston 1.7 10 For Dinner Jo Ellen Bogart 2.4 10 Minutes Till Bedtime Peggy Rathmann 1.5 10,000 Days Of Thunder Philip Caputo 7.6 100 Days Of School Trudy Harris 2.2 100 Inventions That Shaped... Bill Yenne 10 100 Selected Poems E.E. Cummings 7.2 100 Years In Photographs George Sullivan 6.8 1000 Facts About Space Pam Beasant 4.9 1000 Facts About The Earth Moira Butterfield 4.2 1000 Questions And Answers Richard Tames 5.6 1001 Animals to Spot Ruth Brocklehurst 1.6 1001 Things to Spot in the Sea Katie Daynes 2.3 100-Pound Problem, The Jennifer Dussling 2.4 100th Day Of School (Bader) Bonnie Bader 2.1 100th Day Of School, The Angela Shelf Medearis 1.5 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 2.1 100th Day, The Grace Maccarone 1.8 100th Thing About Caroline Lois Lowry 5.5 101 Dalmatians, The Dodie Smith 6.1 101 Hopelessly Hilarious Jokes Lisa Eisenberg 3.1 101 Tips For - A Best Friend Nancy Krulik 4.5 101 Ways To Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 4.8 101 Ways To Bug Your Teacher Lee Wardlaw 4.2 10-Step Guide...Monster Laura Numeroff 1.5 12 Again Sue Corbett 5.7 13 Ghosts: Strange But True.. -

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Peters Township School District MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR READING LEVEL POINTS Abduction, The Korman, Gordon 4 7 After The War Matas, Carol 5.5 7 Alice In April Naylor, Phyllis Reynolds 5.4 7 Alice The Brave Naylor, Phyllis Reynolds 5.2 7 All-Of-A-Kind Family Taylor, Sydney 4.5 7 Amazing But True Sports Storie Hollander, Phyllis 6.1 7 Animal Family, The Jarrell, Randall 4.6 7 Another Day Sachs, Marilyn 5.5 7 Antarctica (Myers) Myers, Walter Dean 8.6 7 Anthem Rand, Ayn 7.9 7 Arly Peck, Robert Newton 6.8 7 Arnold Schwarzenegger (Sexton) Sexton, Colleen 7.1 7 Ashwater Experiment, The Koss, Amy Goldman 6.4 7 Bad Beginning, The Snicket, Lemony 6.1 7 Badger On The Barge & Other... Howker, Janni 6.9 7 Bagthorpes V. The World Cresswell, Helen 6.9 7 Beowulf The Warrior Serraillier, Ian 8.3 7 Beowulf: A New Telling Nye, Robert 5.5 7 Bird Johnson, Angela 4.5 7 Birthday Murderer Bennett, Jay 5.1 7 Black Gold Henry, Marguerite 4.2 7 Black Pearl, The O'Dell, Scott 5.3 7 Blind Date Stine, R. L. 4.4 7 Bone Dance Brooks, Martha 5.9 7 Bone: Eyes Of The Storm Smith, Jeff 3.6 7 Book Of Changes Wynne-Jones, Tim 5.3 7 Book Of Nightmares Peel, John 5.2 7 Book Of Signs Peel, John 5.8 7 Borrowers, The Norton, Mary 4.8 7 Boy In The Moon, The Koertge, Ron 6.7 7 Branded Outlaw Hubbard, L. -

Dancing on Coral Glenda Adams Introduced by Susan Wyndham The

Dancing on Coral Drylands Glenda Adams Thea Astley Introduced by Susan Wyndham Introduced by Emily Maguire The True Story of Spit MacPhee Homesickness James Aldridge Murray Bail Introduced by Phillip Gwynne Introduced by Peter Conrad The Commandant Sydney Bridge Upside Down Jessica Anderson David Ballantyne Introduced by Carmen Callil Introduced by Kate De Goldi A Kindness Cup Bush Studies Thea Astley Barbara Baynton Introduced by Kate Grenville Introduced by Helen Garner Reaching Tin River Between Sky & Sea Thea Astley Herz Bergner Introduced by Jennifer Down Introduced by Arnold Zable The Multiple Effects of Rainshadow The Cardboard Crown Thea Astley Martin Boyd Introduced by Chloe Hooper Introduced by Brenda Niall classics_endmatter_2018.indd 1 21/02/2018 3:20 PM A Difficult Young Man Diary of a Bad Year Martin Boyd J. M. Coetzee Introduced by Sonya Hartnett Introduced by Peter Goldsworthy Outbreak of Love Wake in Fright Martin Boyd Kenneth Cook Introduced by Chris Womersley Introduced by Peter Temple When Blackbirds Sing The Dying Trade Martin Boyd Peter Corris Introduced by Chris Wallace-Crabbe Introduced by Charles Waterstreet The Australian Ugliness They’re a Weird Mob Robin Boyd Nino Culotta Introduced by Christos Tsiolkas Introduced by Jacinta Tynan The Life and Adventures of Aunts Up the Cross William Buckley Robin Dalton Introduced by Tim Flannery Introduced by Clive James The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke The Dyehouse C. J. Dennis Mena Calthorpe Introduced by Jack Thompson Introduced by Fiona McFarlane Careful, He Might Hear