Thank You for Your Interest in Lectio: Prayer on FORMED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Download Christian Spirituality in the Catholic Tradition

CHRISTIAN SPIRITUALITY IN THE CATHOLIC TRADITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jordan Aumann | 326 pages | 01 Aug 1985 | Ignatius Press | 9780898700688 | English | San Francisco, United States Christian Spirituality in the Catholic Tradition PDF Book Hammond C. William James popularized the use of the term "religious experience" in his book The Varieties of Religious Experience. How do you imagine the world? In particular, Philo taught that allegorical interpretations of the Hebrew Scriptures provides access to the real meanings of the texts. Jesuit Missionaries to North America. The matter was referred to the Inquisition. Into Your Hands, Father. Christianity portal Book Category. The Rosary: A Path into Prayer. University of California Press. Click here to sign up. Legend has it that Mary herself gave the Rosary to Dominic. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Each of the religious orders and congregations of the Catholic church, as well as lay groupings, has specifics to its own spirituality — its way of approaching God in prayer to foster its way of living out the Gospel. By: Sohrab Ahmari. Mysticism is not so much a doctrine as a method of thought. Ignatius Loyola. Pastoral Spirituality The monasteries became places of public scandal and the spirituality was measured in terms of worldly pleasure, riches and honour. What was part and parcel of royal court culture was adopted into religious practice. Liberative spirituality centres on the Exodus experience of the people of Israel who encounter Yahweh as the Liberator. Today, the same Christ is in people who are unwanted, unemployed, uncared for, hungry, naked, and homeless. -

“This Translation—The First Into English—Of the Life of Jesus Christ By

“This translation—the first into English—of The Life of Jesus Christ by Ludolph of Saxony will be welcomed both by scholars in various fields and by practicing Christians. It is at the same time an encyclopedia of biblical, patristic, and medieval learning and a compendium of late medieval spirituality, stressing the importance of meditation in the life of individual believers. It draws on an astonishing number of sources and sheds light on many aspects of the doctrinal and institutional history of the Church down to the fourteenth century.” — Giles Constable Professor Emeritus Princeton University “Milton T. Walsh has taken on a Herculean task of translating The Life of Christ by the fourteenth-century Carthusian, Ludolph of Saxony. He has more than risen to the challenge! Ludolph’s text was one of the most widely spread and influential treatments of the theme in the later Middle Ages and has, until now, been available only in an insufficient late nineteenth-century edition (Rigollot). The manuscript tradition of The Life of Christ (Vita Christi) is extremely complex, and Walsh, while basing his translation on the edition, has gone beyond in providing critical apparatus that will be of significant use to scholars, as well as making the text available for students and all interested in the theology, spirituality, and religious life of the later Middle Ages. His introduction expertly places Ludolph’s work in the textual tradition and is itself a contribution to scholarship. Simply put, this is an amazing achievement!” — Eric Leland Saak Professor of History Indiana University “Walsh has done pioneering work unearthing the huge range of patristic, scholastic, and contemporary sources that Ludolph drew upon, enabling us to re-evaluate the Vita as an encyclopedic compilation, skillfully collating a range of interpretations of the gospel scenes to meditational ends. -

Spiritual Struggle and Gregory of Nyssa's Theory of Perpetual Ascent

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-10-2019 Spiritual Struggle and Gregory of Nyssa’s Theory of Perpetual Ascent: An Orthodox Christian Virtue Ethic Stephen M. Meawad Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Ethics in Religion Commons Recommended Citation Meawad, S. M. (2019). Spiritual Struggle and Gregory of Nyssa’s Theory of Perpetual Ascent: An Orthodox Christian Virtue Ethic (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1768 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. SPIRITUAL STRUGGLE AND GREGORY OF NYSSA’S THEORY OF PERPETUAL ASCENT: AN ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN VIRTUE ETHIC A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Stephen M. Meawad May 2019 Copyright by Stephen Meawad 2019 SPIRITUAL STRUGGLE AND GREGORY OF NYSSA’S THEORY OF PERPETUAL ASCENT: AN ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN VIRTUE ETHIC By Stephen M. Meawad Approved December 14, 2018 _______________________________ _______________________________ Darlene F. Weaver, Ph.D. Elizabeth A. Cochran, Ph.D. Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology Director, Ctr for Catholic Intellectual Tradition Director of Graduate Studies (Committee Chair) (Committee Member – First Reader) _______________________________ _______________________________ Bogdan G. Bucur, Ph.D. Marinus C. Iwuchukwu, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology (Committee Member – Second Reader) Chair, Department of Theology Chair, Consortium Christian-Muslim Dial. -

Ordo Virtutum a Musical and Metaphysical Analysis

Hildegard von Bingen’s Ordo Virtutum A Musical and Metaphysical Analysis Michael C. Gardiner VOUCHERS First published 2019 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2019 Michael C. Gardiner The right of Michael C. Gardiner to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record has been requested for this book ISBN: 978-1-138-28858-4 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-26781-4 (ebk) Typeset in Times by Florence Production Ltd, Stoodleigh, Devon VOUCHERS 1 A metaphysical medieval assemblage Introduction At first glance the book in front of you is perhaps an odd, seemingly incongruous amalgam of perspectives: part music theory, part Neoplatonic philosophy, part theology, and equal parts critical theory, phenomenology, and contemporary philosophy. -

Mary and the Rosary Extract

MARY AND THE ROSARY in the light of the Apostolic Letter ‘Rosarium Virginis Mariae’ of Pope John Paul II October 16th, 2002 Hugh Clarke, O.Carm. MARY AND THE ROSARY in the light of the Apostolic Letter Rosarium Virginis Mariae of Pope John Paul II October 16th, 2002 Hugh Clarke, O. Carm. SAINT ALBERT’S PRESS Mary and the Rosary Cover image: The Coronation of the Virgin ceramic by Adam Kossowski, in the Rosary Way at The Friars, Aylesford, Kent. Scripture readings taken from The Jerusalem Bible published and copyright 1966, 1967 and 1968 by Darton, Longman and Todd Ltd., and used by permission of the publishers. Printed in England by Inc Dot Seafire Close, Clifton Moor, York, YO30 4UU First published 2003 Saint Albert’s Press Whitefriars, 35 Tanners Street Faversham, Kent, ME13 7JN, U.K. © British Province of Carmelites ISBN: 0-904849-22-8 Hugh Clarke, O. Carm. CONTENTS Introduction 4 Chapter 1 Prayer 6 The Five S-s 7 Contemplative Prayer 9 Mary — Model of Contemplation 10 Lectio Divina 11 Chapter 2 The Rosary 14 The Year of the Rosary 14 Memories 16 Chapter 3 Rosary Reflections 19 The Joyful Mysteries 20 The Mysteries of Light 22 The Sorrowful Mysteries 25 The Glorious Mysteries 27 The Recitation of the Rosary 29 A Treasure to be Rediscovered 31 Other Suggested Mysteries 33 Distribution of the Mysteries 35 Appendix 1 Pope Leo XIII & Bl. Bartoli Longo 36 Sources and Suggested Reading 38 Notes 39 Mary and the Rosary INTRODUCTION Many people will remember the 1960s, the years of strikes and demonstrations. -

“Guigo II and the Development of Lectio Divina”

“Guigo II and the Development of Lectio Divina” (by Joe Colletti, PhD, July, 2011) Guigo II was a Carthusian monk who died several centuries ago in 1193. His two most renowned writings are the Ladder of Monks and the Twelve Meditations. The Ladder of Monks, which is subtitled "a letter on the contemplative life," is considered one of the first, if not the first, description of the four steps that make up the mystical tradition of Lectio Divina as we know it today. His ladder consists of four rungs termed in Latin as lectio, meditatio, oratio, and contemplatio. According to Guigo, “Reading seeks, meditation finds, prayer asks, contemplation feels.” He further notes that “Reading puts as it were whole food into your mouth; meditation chews it and breaks it down; prayer finds its savour; contemplation is the sweetness that so delights and strengthens. Reading is like the bark, the shell; meditation like the pith, the nut; prayer is in the desiring asking; and contemplation is in the delight of the great sweetness. Reading is the first ground that that precedes and leads one into meditation; meditation seeks busily, and also with deep thought digs and delves deeply to find that treasure; and because it cannot be attained by itself alone, then he sends us into prayer that is mighty and strong. And so prayer rises to God, and there one finds the treasure one so fervently desires, that is the sweetness and delight of contemplation. And then contemplation comes and yields the harvest of the labour of the other three through a sweet heavenly dew, that the soul drinks in delight and joy.” An on-line version of the Ladder of Monks can be found at http://www.umilta.net/ladder.html. -

St. Francis De Sales Church, We Are Committed to Stewardship As Our Way of Life

614 Route 517, Vernon, NJ Mailing Address: P.O. Box 785, McAfee, NJ 07428 Telephone: 973-827-3248 www.stfrancisvernon.org Welcome to St. Francis de Sales Parish We extend a warm welcome to all who attend our Church. We hope you will find our parish community a place where your life of faith will be nourished. Your prayers, your presence, and your talent are most welcome. May God bless all of us. Jesus healing a blind man. We Invite You to Celebrate Eucharist: Saturday (Vigil): 5:00 PM Sunday 8:00 AM 10:00 AM 12:00 PM Morning Mass: Monday through Friday 8:30 AM Saturday (Memorial Mass) 8:30 AM Holy Days : 7:00 AM 8:30 AM 12:00 PM 7:30 PM Reconciliaon : Saturday 4:00 - 4:45 PM Adoraon : First Friday 9:00AM - 9:00PM Subsequent Fridays 9:00AM - 12:00PM ___________________________________________________________________________________ Served By: Rev. Brian P. Quinn, Pastor Deacon Dennis Gil Mission Statement As a parish family of St. Francis de Sales Church, we are committed to stewardship as our way of life. We place God first in all things. Centered in the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist, we devote ourselves to proclaim the Gospel. We are dedicated to grow as a faith community to holiness through prayer, sacraments and service to all God’s people. St. Francis de Sales Church St. Francis Fourth Sunday of Lent March 26, 2017 The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. — Psalm 23:1 Page Two March 26, 2017 SATURDAY MEMORIAL MASS The 8:30AM Saturday Mass during 25 - Saturday the month of March will be of- 8:30 AM Saturday Memorial Mass 5:00 PM Robert Baldwin Sr. -

Notre Dame Seminary School of Theology Professor: Archbishop

Notre Dame Seminary School of Theology Professor: Archbishop Alfred C. Hughes Time: MWF 9:00 – 9:50 a.m. E-mail: [email protected] Room: 1 SpT 501 - Spiritual Theology Syllabus I Course Description This course introduces the student to the Christian spiritual teaching of the Catholic Church. The two-fold purpose is to present in a systematic fashion the fundamental elements in the living of the Christian spiritual life and to introduce the student at the same time to Christian spiritual classics which illustrate these elements. II Course Rationale: A candidate for the priesthood needs to embrace a Christian spiritual life based on a sound understanding of the faith realities which undergird it. Exposure to the Christian spiritual classics introduces him to reliable spiritual reading for continuing spiritual formation. Both of these ends will lay a theological foundation for the spiritual guidance of others. III Envisioned Outcomes: Students will learn the basic stepping-stones in the journey of the Christian spiritual life. Students will appreciate the theological structure of the Christian spiritual life. Students will be introduced to thirteen Christian spiritual classics for continuing support of their own spiritual journey. Students will be acquainted with the basic theological understanding of the faith realities involved in helping others become disciples of the Lord. IV Instructional Methods: Lecture Class reflection on reading of classics V Requirements and Important Dates A. Read entire text and assigned portions of spiritual classics B. Two exams: October 24 and final exam week C. Reflective paper due three weeks after topic has been treated in class D. -

Fyp Lecture Schedule 2018-19 Section I

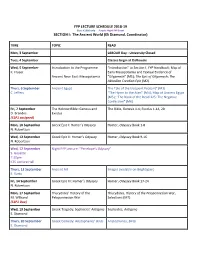

FYP LECTURE SCHEDULE 2018-19 Blue: K1000 only Purple: Night FYP Event SECTION I: The Ancient World (Eli Diamond, Coordinator) TIME TOPIC READ Mon, 3 September LABOUR Day - University Closed Tues, 4 September Classes begin at Dalhousie Wed, 5 September Introduction to the Programme “Introduction” to Section I, FYP Handbook; Map of K. Fraser Early Mesopotamia and Textual Evidence of Ancient Near East: Mesopotamia “Gilgamesh” (M1); The Epic of Gilgamesh; The Akkadian Creation Epic (M2) Thurs, 6 September Ancient Egypt The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant” (M3) C. Jeffers “The Hymn to the Aten” (M4); Map of Ancient Egypt (M5); "The Book of the Dead 125: The Negative Confession" (M6) Fri, 7 September The Hebrew Bible: Genesis and The Bible, Genesis 1-4; Exodus 1-14, 20 D. Brandes Exodus (S1P1 assigned) Mon, 10 September Greek Epic I: Homer’s Odyssey Homer, Odyssey Book 1-8 N. Robertson Wed, 12 September Greek Epic II: Homer’s Odyssey Homer, Odyssey Book 9-16 N. Robertson Wed, 12 September Night FYP Lecture: “Penelope’s Odyssey” S. Goyette 7:30pm KTS Lecture Hall Thurs, 13 September Ancient Art Images available on Brightspace E. Varto Fri, 14 September Greek Epic III: Homer’s Odyssey Homer, Odyssey Book 17-24 N. Robertson Mon, 17 September Thucydides’ History of the Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, M. Wilband Peloponnesian War Selections (M7) (S1P1 Due) Wed, 19 September Greek Tragedy: Sophocles’ Antigone Sophocles, Antigone E. Diamond Thurs, 20 September Greek Comedy: Aristophanes’ Birds Aristophanes, Birds E. Diamond Fri, 21 September Plato I: Republic and Symposium Plato, The Republic (Sun, Line, Cave images) (M8) E. -

Meditation and Contemplation in High to Late Medieval Europe

K ARL B AIER Meditation and Contemplation in High to Late Medieval Europe In the Western European history of meditation and contemplation the period from the 12th to the 15th century differs significantly from the times both before and after. Earlier forms undergo important changes and the foundations are laid for spiritual practices of which several dominated until the 20th century. Four trends are of special importance: • The development of elaborate philosophical and theological theories which treat meditation and contemplation systematically. • The democratization of meditation and contemplation. • The emergence of new methods, especially imaginative forms of meditation. • The differentiation between meditation and contemplation and their establishment as methods in their own right accompanied by discus- sions about their relation and the transition from one to the other. The following article will treat these trends and other related develop- ments concentrating on Richard of St. Victor, the Scala Claustralium of Guigo II and the Clowde of Unknowyng. A. RICHARD OF ST. VICTOR’S EPISTEMOLOGICAL APPROACH The Regular Canons of St. Victor, an abbey outside the city walls of Paris, ran one of the most famous schools for higher education in the 12th century. They developed a new form of philosophy and theology, unifying the monastic mystical tradition and spiritual practice with a spirit of critical reflection and systematical thinking typical of the rising scholasticism. In a practical and theoretical sense the Victorines con- nected science with a specific form of life.1 1 Cf. S. Jaeger, Humanism and ethics at the School of St. Victor in the early twelfth Century, in: Mediaeval Studies 55 (1993) 51-79. -

The Solitary Life

THE SOLITARY LIFE A Letter of Guigo 5th Prior of the Grande Chartreuse INTRODUCED AND TRANSLATED FROM THE LATIN BY THOMAS MERTON MONASTERY CEMETERY CROSS Charterhouse of the Transfiguration 2006 CARTHUSIAN BOOKLETS SERIES, N° 6 THE SOLITARY LIFE A Letter of Guigo, 5th Prior of the Grande Chartreuse. Written about 1135, in the last days of his priorate, to an unknown friend. Introduced and translated from the Latin by Thomas Merton COPYRIGHT © 1977 BY THE TRUSTEES OF THE THOMAS MERTON LEGACY TRUST N INTRODUCTION Guigo is one of those extraordinary figures in literature and in spirituality who, unknown and perhaps in some sense inaccessible to the many, have been accorded the most unqualified admiration by the discerning few. Thirty years ago Dom Wilmart, editing Guigo’s Meditations, did not hesitate to say that he considered this little book “the most original work that has come down to us from the truly crea- tive period of the middle ages.” No small praise when we reflect who Guigo’s contemporaries were! Dom Wilmart names a few: not only Hildebert, William de Conches, Bernard of Chartres, Honorius “of Autun”, Gilbert de la Porrée, but even Abelard, Hugh of St. Victor and St. Bernard himself. The opinion is neither rash nor even new. The very ones Wilmart names were among the first to praise Guigo without reservation. Peter the Venerable called him “the fairest flower of our religion.” We know what effect the Meditations of Guigo had on Bernard of Clairvaux (see St. Bernard, Letter XI). Some of the most fundamental ideas in Bernard’s own doctrine of love were in- 1 spired by his Carthusian friend. -

Birthing Jesus: a Salesian Understanding of the Christian Life

STUDIES IN SALESIAN SPIRITUALITY WENDY WRIGHT, PH.D. Birthing Jesus: A Salesian Understanding of the Christian Life originally published in Studia Mystica 13/1 (March 1990): 23-44 Our souls must give birth, not outside themselves but inside themselves, to the sweetest, gentlest and most beautiful male child imaginable. It is Jesus whom we must bring to birth and produce in ourselves. You are pregnant with him, my dear sister, and blessed by God who is his Father.¹ When Francis de Sales, early seventeenth century bishop and spiritual advisor, wrote these words to his friend and advisee Jane de Chantal, he was asserting his belief that the ultimate meaning of human life is to be found in bringing Jesus into the world. The core of Salesian spirituality, that tradition of Christian devotion articulated by de Sales and de Chantal, can in fact be summed up in the phrase “Live Jesus!”² These two pregnant words are packed with theological claims. They assert that the divine enters history and takes flesh through the medium of the human person. They affirm that this can happen at any point in history. The individual, like the Virgin Mary, can be a mother of God. He or she becomes so by being receptive to the Spirit of God which hovers in anticipation around the human soul, desiring to enter it, to cause it to conceive and then give birth, making divine life present in the world. The purpose of this article is to look closely at this maternal symbolism associated with the Virgin Mary, which is so foundational to the Salesian conception of the Christian life and in so doing make three assertions about it.