Emerging Youth Publics in Late Colonial Uttarakhand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As Rich in Beauty As in Historic Sites, North India and Rajasthan Is a Much Visited Region

India P88-135 18/9/06 14:35 Page 92 Rajasthan & The North Introduction As rich in beauty as in historic sites, North India and Rajasthan is a much visited region. Delhi, the entry point for the North can SHOPPING HORSE AND CAMEL SAFARIS take you back with its vibrancy and Specialities include marble inlay work, precious Please contact our reservations team for details. and semi-precious gemstones, embroidered and growth from its Mughal past and British block-printed fabrics, miniature Mughal-style FAIRS & FESTIVALS painting, famous blue pottery, exquisitely carved Get caught up in the excitement of flamboyant rule. The famous Golden Triangle route furniture, costume jewellery, tribal artefacts, and religious festivals celebrated with a special local starts here and takes in Jaipur and then don't forget to get some clothes tailor-made! farvour. onwards to the Taj Mahal at Agra. There’s SHOPPING AREAS Feb - Jaisalmer Desert Festival, Jaisalmer Agra, marble and stoneware inlay work Taj so much to see in the region with Mughal complex, Fatehbad Raod and Sabdar Bazaar. Feb - Taj Mahotsav, Agra influence spreading from Rajasthan in Delhi, Janpath, Lajpat Nagar, Chandini Chowk, Mar - Holi, North India the west to the ornate Hindu temples of Sarojini Nagar and Ajmal Khan Market. Mar - Elephant Festival, Jaipur Khajuraho and Orcha in the east, which Jaipur, Hawa Mahal area, Chowpars for printed Apr - Ganghur Festival, Rajasthan fabrics, Johari Bazaar for jewellery and gems, leads to the holy city of Varanasi where silverware etc. Aug - Sri Krishna Janmasthami, Mathura - Vrindavan pilgrims gather to bathe in the crowded Jodhpur, Sojati Gate and Station area, Tripolia Bazaar, Nai Sarak and Sardar Market. -

Linguistics Development Team

Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Pramod Pandey Centre for Linguistics / SLL&CS Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Email: [email protected] Paper Coordinator: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Department of Linguistics, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, Pune- 411006, [email protected] Content Writer: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Prof H. S. Ananthanarayana Content Reviewer: Retd Prof, Department of Linguistics Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family Description of Module Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Historical and Comparative Linguistics Module Title Indo-Aryan Language Family Module ID Lings_P7_M1 Quadrant 1 E-Text Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE FAMILY The Indo-Aryan migration theory proposes that the Indo-Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes into South Asia during the early part of the 2nd millennium BCE, bringing with them the Indo-Aryan languages. Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between Western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument is supported by archaeological and anthropological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. -

Azadari in Lucknow

WEEKLY www.swapnilsansar.orgwww.swapnilsansar.org Simultaneously Published In Hindi Daily & Weekly VOL24, ISSUE 35 LUCKNOW, 07 SEPTEMBER ,2019,PAGE 08,PRICE :1/- Azadari in Lucknow Agency.Inputs With Sajjad Baqar- Lucknow is on the whole favourable to Madhe-Sahaba at a public meeting, and in protested, including prominent Shia Adeeb Walter -Lucknow.Azadari in Shia view." The Committee also a procession every year on the barawafat figures such as Syed Ali Zaheer (newly Lucknow is name of the practices related recommended that there should be general day subject to the condition that the time, elected MLA from Allahabad-Jaunpur), to mourning and commemoration of the prohibition against the organised place and route thereof shall be fixed by the Princes of the royal family of Awadh, district authorities." But the Government the son of Maulana Nasir a respected Shia failed to engage Shias in negotiations or mujtahid (the eldest son, student and inform them beforehand of the ruling. designated successor of Maulana Nasir Crowds of Shia volunteer arrestees Hussain), Maulana Sayed Kalb-e-Husain assembled in the compound of Asaf-ud- and his son Maulana Kalb-e-Abid (both Daula Imambada (Bara Imambara) in ulema of Nasirabadi family) and the preparation of tabarra, April 1939. brothers of Raja of Salempur and the Raja The Shias initiated a civil of Pirpur, important ML leaders. It was disobedience movement as a result of the believed that Maulana Nasir himself ruling. Some 1,800 Shias publicly Continue On Page 07 Imambaras, Dargahs, Karbalas and Rauzas Aasafi Imambara or Bara Imambara Imambara Husainabad Mubarak or Chhota Imambara Imambara Ghufran Ma'ab Dargah of Abbas, Rustam Nagar. -

(Муссури) Travel Guide

Mussoorie Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/mussoorie page 1 Max: 19.5°C Min: Rain: 174.0mm 23.20000076 When To 2939453°C Mussoorie Jul Mussorie is a picturesque hill Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, VISIT umbrella. station that offers enchanting view Max: 17.5°C Min: Rain: 662.0mm of capacious green grasslands and 23.60000038 http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-mussoorie-lp-1145302 1469727°C snow clad Himalayas. A sublime Famous For : City Aug valley adorned with flowers of Jan Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, different colors, cascading From plush flora and fauna to rich cultural Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, umbrella. waterfalls and streams is just a heritage, Mussoorie is a hill station that has umbrella. Max: 17.5°C Min: Rain: 670.0mm 23.10000038 everything to attract any traveler. Popularly Max: 6.0°C Min: Rain: 51.0mm 1469727°C feast to eyes. 6.800000190 known as "the Queen of the Hills", the hill is 734863°C Sep at an elevation of 6,170 ft, thus making it a Feb Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, perfect destination to avoid scorching heat Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, umbrella. of plains. The number of places to visit in umbrella. Max: 16.5°C Min: Rain: 277.0mm 21.29999923 Mussoorie are more than anyone can wish Max: 7.5°C Min: Rain: 52.0mm 7060547°C 9.399999618 for. Destinations like Kempty Falls, Lake 530273°C Oct Mist, Cloud End, Mussoorie Lake and Jwalaji Mar Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, Temple are just the tip of the iceberg. -

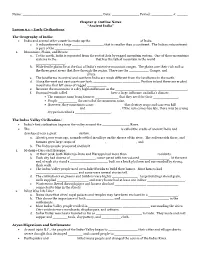

Chapter 9: Outline Notes “Ancient India” Lesson 9.1 – Early Civilizations

Name: ______________________________________ Date: _____________ Period: __________ #: _____ Chapter 9: Outline Notes “Ancient India” Lesson 9.1 – Early Civilizations The Geography of India: India and several other countries make up the _______________________ of India. o A subcontinent is a large _______________ that is smaller than a continent. The Indian subcontinent is part of the ____________. 1. Mountains, Plains, and Rivers: a. To the north, India is separated from the rest of Asia by rugged mountain system. One of these mountains systems in the __________________ that has the tallest mountain in the world ____________ ______________. b. Wide fertile plains lie at the foot of India’s extensive mountain ranges. The plains owe their rich soil to the three great rivers that flow through the region. These are the _________, Ganges, and ________________________ rivers. c. The landforms in central and southern India are much different from the landforms in the north. d. Along the west and east coasts are lush ______________ ________. Further inland there are eroded mountains that left areas of rugged _________. e. Between the mountains is a dry highland known as the ____________________ ______________. f. Seasonal winds called ____________________ have a large influence on India’s climate. The summer rains bring farmers ___________ that they need for their ____________. People _________ the arrival of the monsoon rains. However, they sometimes cause ______________ that destroy crops and can even kill _______________ and ________________. If the rain comes too late, there may be a long dry period called a _________________. The Indus Valley Civilization: India’s first civilization began in the valley around the _____________ River. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project: Rehabilitation of Damaged Roads in Dehradun

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 47229-001 December 2014 IND: Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project Submitted by Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project (Roads & Bridges), Government of Uttarakhand, Dehardun This report has been submitted to ADB by the Program Implementation Unit, Uttarkhand Emergency Assistance Project (R&B), Government of Uttarakhand, Dehradun and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Initial Environmental Examination July 2014 India: Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project Restoration Work of (1) Tyuni–Chakrata-Mussoorie–Chamba–Kiriti nagar Road (Package No: UEAP/PWD/C23) (2) Kalsi- Bairatkhai Road (Package No: UEAP/PWD/C24) (3) Ichari-Kwano-Meenus Road (Package No: UEAP/PWD/C38) Prepared by State Disaster Management Authority, Government of Uttarakhand, for the Asian Development Bank. i ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank ASI - Archaeological Survey of India BOQ - Bill of Quantity CTE - Consent to Establish CTO - Consent to Operate DFO - Divisional Forest Officer DSC - Design and Supervision Consultancy DOT - Department of Tourism CPCB - Central Pollution Control Board EA - Executing Agency EAC - Expert Appraisal Committee EARF - Environment Assessment and Review Framework EC - Environmental Clearance EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMMP - Environment Management and Monitoring Plan EMP - Environment Management Plan GoI - Government of India GRM - Grievance Redressal Mechanism IA - -

The Constitution . Amendment) Bill

LOK SABHA THE CONSTITUTION (NINTH . AMENDMENT) BILL, 1956 .. (Report of Joint Committee) PRI!s!!NTED ON THB 16TH JULY, 1956 W,OK SABHA SECRETARIAT . NEWDELID Jaly, 1956 CONTBNTS PAOBS r. Composition of the Joblt Comminoe i-ii ;z. Report of the Joint Committee iif-iv 3· Minutes of Dissent • vii-xv 4o Bill as omended by the Joint Committee 1-18 MPBNDIX I- Modon In the Lok_Ssbha for refe=ce of the Bill to Joint Coum:U.ttee • • • • • • • • 19-20 APPINDDI II- Motion in the Rsjya Sabha 21 Anmmo: m- Minutes of the littfnts of the Joint Committee • APPl!NDIX A APPIINDIX B THE CONSTITUTION (NINTH AMENDMENT) BILL, 1956 _ Composition of the Joint Committee Shri Govind Ballabh Pant-Chainnan. MEMBERs Lok Sabha 2. Shri U. Srinivasa Malliah 3. Shri H. V. Pataskar 4. Shri A. M. Thomas 5. Shri R. Venkataraman 6. Shri S. R. Rane 7. Shri B. G. Mehta 8. Shri Basanta Kumar Das 9. Dr. Ram Subhag Singh 10. Pandit Algu Rai Shastri 11. Shri Dev Kanta Borooah 12. Shri S. Nijalingappa 13. Shri S. K. Patil 14. Shri Shriman Narayan 15. Shri G. S. Altekar - 16. Shri G. B. Khedkar 17. Shri Radha Charan Sharma 18. 'shri GUrm.~ Singh Musafi~ 19. Shri i:l.am PiaLop 'Gai-g 20. Shri Bhawanji A. Khimji. 21. Shri P. Ramaswamy - · 22. Shri B. N. Datar ·: 23. Shri Anandchand 24. Shri Frank Anthony 25. Shri P. T. Punnoose 26. Shri K. K. Basu 27. Shri.J. B. Kripalani 28. Shri Asoka Mehta 29. Shri Sarangadhar Das 30. Shri N. -

Hindi and Urdu (HIND URD) 1

Hindi and Urdu (HIND_URD) 1 HINDI AND URDU (HIND_URD) HIND_URD 111-1 Hindi-Urdu I (1 Unit) Beginning college-level sequence to develop basic literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari script only. Prerequisite - none. HIND_URD 111-2 Hindi-Urdu I (1 Unit) Beginning college-level sequence to develop basic literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari script only. Prerequisite: grade of at least C- in HIND_URD 111-1 or equivalent. HIND_URD 111-3 Hindi-Urdu I (1 Unit) Beginning college-level sequence to develop basic literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari script only. Prerequisite: grade of at least C- in HIND_URD 111-2 or equivalent. HIND_URD 116-0 Accelerated Hindi-Urdu Literacy (1 Unit) One-quarter course for speakers of Hindi-Urdu with no literacy skills. Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts; broad overview of Hindi-Urdu grammar. Prerequisite: consent of instructor. HIND_URD 121-1 Hindi-Urdu II (1 Unit) Intermediate-level sequence developing literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts. Prerequisite: grade of at least C- in HIND_URD 111-3 or equivalent. HIND_URD 121-2 Hindi-Urdu II (1 Unit) Intermediate-level sequence developing literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts. Prerequisite: grade of at least C- in HIND_URD 121-1 or equivalent. HIND_URD 121-3 Hindi-Urdu II (1 Unit) Intermediate-level sequence developing literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts. Prerequisite: grade of at least C- in HIND_URD 121-2 or equivalent. HIND_URD 210-0 Hindi-Urdu III: Topics in Intermediate Hindi-Urdu (1 Unit) A series of independent intermediate Hindi-Urdu courses, developing proficiency through readings and discussions. -

F. No. 10-6/2017-IA-Ill Government of India

F. No. 10-6/2017-IA-Ill Government of India Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (IA.III Section) Indira Paryavaran Bhawan, Jor Bagh Road, New Delhi - 3 Date: 10th October, 2017 To, Mukhya Nagar Adhikari Haldwani Nagar Nigam, Nagar Palika Parishad, Haldwani, District: Nainital - 263139, Uttarakhand E Mail: infoRnagarnigamhaldwani.com Subject: Integrated Municipal Solid Waste Management Project at Haldwani - Kathgodam, District Nainital, Uttarakhand by M/s Haldwani Nagar Nigam - Environmental Clearance - reg. Sir, This has reference to your online proposal No. IA/UK/MIS/62412/2015 dated 9th February 2017, submitted to this Ministry for grant of Environmental Clearance (EC) in terms of the provisions of the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006 under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. 2. The proposal for grant of environmental clearance to the project 'Integrated Municipal Solid Waste Management Project at Haldwani-Kathgodam, District Nainital, Uttarakhand promoted by M/s Haldwani Nagar Nigam' was considered by the Expert Appraisal Committee (Infra-2) in its meetings held on 12-14 April, 2017 and 21-24 August, 2017. The details of the project, as per the documents submitted by the project proponent, and also as informed during the above meeting, are under:- (i) The project involves Integrated Municipal Solid Waste Management Project at Haldwani- Kathgodam, District Nainital, Uttarakhand promoted by M/s Haldwani Nagar Nigam. (ii) As a part of the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), Haldwani Nagar Nigam (HNN) has proposed treatment and disposal of MSW at Indira Nagar railway crossing on Sitarganj bypass, Haldwani. (iii) Integrated Municipal Solid Waste Management Facility has been taken up to cater the Haldwani City, Bhimtal, Kichha, Lalkuan and Rudrpur under administrative control of Haldwani Nagar Nigam. -

Dehradun, India Sdgs Cities Challenge Snapshot

SDGs Cities Challenge Module Three Dehradun, India SDGs Cities Challenge Snapshot Challenge Overview Urban service delivery in Dehradun is facing increasing stress due to high levels of urbanisation and governance gaps in the service delivery architecture. Dehradun, being the state capital, caters to a wide range of institutional, educational and tourism needs. The provisioning of urban infrastructure in the city – both quantity and quality - has not kept pace with the rapid rate of urbanisation over the past two decades. RapidThe extremely urbanisation, narrow coupled roads in with the core unprecedented city area, inadequate growth in traffic management numberthroughout of register the city edand vehicles a general and lack influx of proper of vehicles road hierarchy on city requires a sustained roadseffort overfrom a surrounding period of time areas, to reorganise has contributed the road tosector. large Public-scale transport, which is in increasea rudimentary of traffic state, in alsothe city.requires The largeextremely scale investmentnarrow roads to supportin economic activity thecommensurate core city area, with inadequate the growth trafficpotential. management With more than 300 schools in the city, the throughoutincreasing intensity the city of and traffic a general has resulted lack of in proper traffic congestion road and delays and increased accidents and pollution levels. which pose potential threat to the safety hierarchy requires a sustained effort over a period to and security of school students during their commute to schools. reorganise the road sector. Our proposal calls for a child friendly mobility plan for the city, with Our challenge is to plan our urban communities and city- emphasis on providing access to safe and affordable mobility systems in neighbourhoods in a way that makes the city accessible to their journey between home and school. -

On Documenting Low Resourced Indian Languages Insights from Kanauji Speech Corpus

Dialectologia 19 (2017), 67-91. ISSN: 2013-2247 Received 7 December 2015. Accepted 27 April 2016. ON DOCUMENTING LOW RESOURCED INDIAN LANGUAGES INSIGHTS FROM KANAUJI SPEECH CORPUS Pankaj DWIVEDI & Somdev KAR Indian Institute of Technology Ropar*∗ [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract Well-designed and well-developed corpora can considerably be helpful in bridging the gap between theory and practice in language documentation and revitalization process, in building language technology applications, in testing language hypothesis and in numerous other important areas. Developing a corpus for an under-resourced or endangered language encounters several problems and issues. The present study starts with an overview of the role that corpora (speech corpora in particular) can play in language documentation and revitalization process. It then provides a brief account of the situation of endangered languages and corpora development efforts in India. Thereafter, it discusses the various issues involved in the construction of a speech corpus for low resourced languages. Insights are followed from speech database of Kanauji of Kanpur, an endangered variety of Western Hindi, spoken in Uttar Pradesh. Kanauji speech database is being developed at Indian Institute of Technology Ropar, Punjab. Keywords speech corpus, Kanauji, language documentation, endangered language, Western Hindi DOCUMENTACIÓN DE OBSERVACIONES SOBRE LENGUAS HINDIS DE POCOS RECURSOS A PARTIR DE UN CORPUS ORAL DE KANAUJI Resumen Los corpus bien diseñados y bien desarrollados pueden ser considerablemente útiles para salvar la brecha entre la teoría y la práctica en la documentación de la lengua y los procesos de revitalización, en la ∗* Indian Institute Of Technology Ropar (IIT Ropar), Rupnagar 140001, Punjab, India.