An Evaluation of Kazakhstan's Financial System Reforms in 1993

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HALYK AR English Version Final 28 04 18.Cdr

ANNUAL REPORT 1 2017 1 2 3 4 5 AT A GLANCE BUSINESS MODEL CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD'S CHAIRPERSON OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 4 8 STATEMENT MANAGEMENT BOARD'S 19 11 REVIEW 15 6 7 8 9 10 MANAGEMENT BOARD KEY EVENTS IN 2017 AWARDS MACROECONOMIC FINANCIAL REVIEW 25 31 35 AND BANKING REVIEW 43 38 11 12 13 14 15 BUSINESS REVIEW RISK MANAGEMENT SOCIAL REPORT CORPORATE GOVERNANCE RESPONSIBILITY STATEMENT 49 60 69 78 93 16 17 18 OUTLOOK CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL INFORMATION 96 STATEMENTS AND INDEPENDENT FOR SHAREHOLDERS AUDITORS' REPORT FOR THE 186 YEARS ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2017, 2016 AND 2015 100 1 BE THE LEADER! LEAD FROM THE FRONT! AT A GLANCE FLAGSHIP The word flagship denotes the lead ship in a fleet. The name is usually given to the best and largest ships, expeditions and taskforces. A flagship, as a rule, is a command and control ship for a commander, flag officer or headquarters and display's the senior officer's flag. 4 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS1 NUMBER OF CUSTOMERS/ACCOUNTS AT YEAR-END Key ratios Halyk Bank + Kazkommertsbank Halyk Bank Key figures at year-end 01.01.2018 01.01.2017 01.01.2018 01.01.2018 01.01.2017 KZT mln US$ mln* KZT mln US$ mln* Retail accounts, mln 8.5 5.9 5.4 Loans to customers 3,251,102 9,783 2,319,583 6,960 Corporate clients 3,935 1,672 1,621 Total assets 8,857,781 26,654 5,348,483 16,048 Payment cards, mln 9.0 6.3 5.5 Amounts due to customers 6,131,750 18,451 3,820,662 11,464 Retail loans, mln 0.9 0.68 0.67 Debt securities issued 962,396 2,896 584,933 1,755 Mortgage loans 40,761 20,012 21,455 Amounts due to credit institutions 255,151 -

LEGAL REGULATION of Npos' FUNDRAISING ACTIVITIES USING

An Analytical Overview LEGAL REGULATION OF NPOs’ FUNDRAISING ACTIVITIES USING NON-CASH PAYMENT SYSTEMS IN THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN1 PREPARED FOR International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) PREPARED BY Roza Salibekova 1 This overview is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the sole responsibility of ICNL and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. © ICNL, 2018 Translated from Russian Written and compiled by Roza Salibekova Legal Regulation of NCOs’ Fundraising Activities Using Non-Cash Payment Systems in the Republic of Kazakhstan / Written and compiled by Roza Salibekova. This overview is designed to inform private individuals and not-for-profit organizations about the key provisions of the Kazakh legislation that NCOs have to comply with in raising funds from legal and physical persons via non-cash payment facilities. Based on a comprehensive analysis of applicable Kazakh legislation, the study contains information of educational and practical value. Intended for a broad readership. DISCLAIMER. The materials presented in this handbook are intended for general use. No action or inaction should be taken based solely on the contents of this information, which cannot be regarded as legal advice. ICNL shall not be responsible for the accuracy and completeness of information in this handbook or any consequences of its use. Readers should consult with a legal professional on any specific legal matter before acting on any of the information presented. © International Center for Not-for-profit Law, 2018 © ICNL, 2018 2 Contents Goals and Objectives 4 Facts and Background 4 1. -

From Two to Six People of 350-550 Kilograms

1 BOLD ACCOMPLISHMENTS from two to six people of 350-550 kilograms The first woman to fly in a hot air balloon was1784 the 19-year-old Frenchwoman Elisabeth Thible. The flight was made in a hot air balloon called La Gustave in 1784 and lasted 45 minutes. The opera singer dressed as the goddess Minerva bravely climbed into it, amazing the crowd. A confident ascent Hot air balloons lift from two to six people into the air with a maximum payload of 350-550 kilograms. The world record holder is a 35-seat balloon with a two-story gondola. 2 2 4 Glossary 6 Chairman of the Board of Directors 8 Board of Directors 12 Chairman of the Bank's Management Board 14 Management Board of the Bank 21 Executive Summary 23 Shareholders and Capital. Dividend Policy 25 A Brief History of Bank CenterCredit 27 Overview of the macroeconomics and banking sector of the Republic of Kazakhstan 30 Review of Financial Performance 38 Overview of Core Operations 56 Risk Management System 60 Internal Control and Audit System 63 Information on the amount and composition of remuneration for members of the Board of Directors and the Management Board of the Bank for 2017. 64 Social Responsibility and Environmental Protection 69 Corporate Governance 77 Subsidiaries 79 Key Goals and Objectives for 2018 80 Information for Shareholders 83 Independent Auditors Report 2 3 1 ADB Asian Development Bank 2 ABS Automated banking system 3 Colvir ABS/Colvir Banking System Colvir is the Bank's current IT platform 4 AIS LEA Automated Information System for Law Enforcement Agencies 5 Damu EDF JSC / Damu Fund Damu Enterprise Development Fund JSC 6 ATM (Eng. -

US General Purpose Brands Purchase Volume In

FOR 46 YEARS, THE LEADING PUBLICATION COVERING PAYMENT SYSTEMS WORLDWIDE FEBRUARY 2017 / ISSUE 1103 Mastercard and Visa — U.S. 2016 Mastercard and Visa credit, debit, and prepaid cards issued in the U.S. General Purpose Brands U.S. generated $4.326 trillion in purchase volume (spending at merchants) in 2016, an increase of 9.5% over 2015. All consumer Purchase Volume in 2016 (Tril.) and commercial card products are included in that amount. > see p. 9 with Change vs. 2015 Alipay QR Code Payments to the U.S./Canada up $1.549 Visa Alipay, the largest processor of online and mobile payments in 15% Credit China, is building brick and mortar merchant acceptance networks for its mobile wallet product in the U.S. and Canada to serve up Visa $1.465 visiting Chinese consumers. The company says that more than Debit 7% > see p. 5 Sionic Mobile’s Rewards Marketplace down American $0.695 Airlines, hotels, car manufacturers, mobile network operators, 3% Express large retailers, and other enterprises that offer mobile apps for customer loyalty see opportunities to “earn and burn” rewards Mastercard up $0.693 points at each other’s locations. One example of earn and burn Credit 6% > see p. 12 Overdraft Credit for Millennials up $0.619 Mastercard Debit The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau says that revenues to 7% financial institutions in the U.S. from overdrafts consumers made from their demand deposit accounts (DDA), commonly known up Discover $0.121 as checking accounts, totaled $17 billion in 2016. The typical 3% > see p. 7 ID Insight Fights Account Takeover Fraud © 2017 The Nilson Report When ID Insight started offering products in 2003 to combat takeover of an existing account as well as fraud tied to opening a new account in the name of an unsuspecting existing cardholder, General Purpose Cards — U.S. -

'Halyk Savings Bank of Kazakhstan' Consolidated

17 November 2017 Joint Stock Company ‘Halyk Savings Bank of Kazakhstan’ Consolidated financial results for the nine months ended 30 September 2017 Joint Stock Company ‘Halyk Savings Bank of Kazakhstan’ and its subsidiaries (together “the Bank”) (LSE: HSBK) releases its condensed interim consolidated financial information for the nine months ended 30 September 2017. Umut Shayakhmetova, the Bank’s CEO commented: “The third quarter has been marked by the acquisition of Kazkommertsbank. In the past few months, we have been working intensively on integration of our new subsidiary, bringing all policies, risk and cost control to Halyk Bank’s standard and making necessary changes in KKB management team. The strategy for the enlarged Halyk Group is under development and to be announced by the end of the year. However, we believe our first joint consolidated results with KKB look promising.” Statement of profit or loss review Change, Change, 9m 2017 9m 2016 abs Y-o-Y, % 3Q 2017 3Q 2016 abs Y-o-Y, % Interest income 339,052 244,046 95,006 38.9% 154,347 86,175 68,172 79.1% Interest expense -172,236 -118,844 -53,392 44.9% -86,314 -40,092 -46,222 2.2x Net interest income before impairment 166,816 125,202 41,614 33.2% 68,033 46,083 21,950 47.6% charge Fee and commission 58,880 42,292 16,588 39.2% 28,893 14,700 14,193 96.6% income Fee and commission -16,029 -8,427 -7,602 90.2% -9,922 -2,324 -7,598 4.3x expense Net fee and 42,851 33,865 8,986 26.5% 18,971 12,376 6,595 53.3% commission income Insurance income(1) 3,560 1,899 1,661 87.5% 2,358 759 1,599 -

Joint Stock Company 'Halyk Savings Bank Of

18 May 2018 Joint Stock Company ‘Halyk Savings Bank of Kazakhstan’ Consolidated financial results for the three months ended 31 March 2018 Joint Stock Company ‘Halyk Savings Bank of Kazakhstan’ and its subsidiaries (together “the Bank”) (LSE: HSBK) releases its condensed interim consolidated financial information for the three months ended 31 March 2018. Statement of profit or loss review Change, 1Q 2018 4Q 2017 abs Q‐o‐Q, % Interest income 162,005 167,276 ‐5,271 ‐3.2% Interest expense ‐87,617 ‐ 85,569 ‐2,048 2.4% Net interest income before credit loss expense 74,388 81,707 ‐7,319 ‐9.0% Fee and commission income 26,374 28,760 ‐2,386 ‐8.3% Fee and commission expense ‐9,680 ‐10,703 1,023 ‐9.6% Net fee and commission income 16,694 18,057 ‐1,363 ‐7.5% Insurance income(1) 292 2,933 ‐2,641 ‐90.0% FX operations(2) 55,425 43,216 12,209 28.3% Loss from derivative operations and securities (3) ‐42,546 ‐27,877 ‐14,669 52.6% Other non‐interest income 15,764 14,179 1,585 11.2% Credit loss expense (4) ‐5,197 ‐43,149 37,952 ‐88.0% Recoveries of other credit loss expense(5) 1,355 1,275 80 6.3% Operating expenses ‐36,084 ‐46,216(6) 10,132 ‐21.9% Income tax expense ‐10,159 ‐8,167 -1,992 24.4% Profit from discontinued operations 2,585 2,134 451 21.1% Non‐controlling interest in net income ‐10,464 ‐51 ‐10,413 205.2x Net income 62,053 38,041 24,012 63.1% Net interest margin, p.a. -

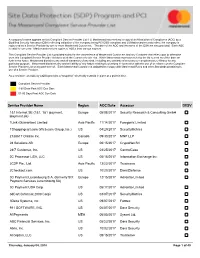

Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV

A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) Mastercard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) Mastercard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more Mastercard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. Mastercard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of Mastercard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While Mastercard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, Mastercard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. Mastercard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each Mastercard Customer is obligated to comply with Mastercard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Compliant Service Provider 1-60 Days Past AOC Due Date 61-90 Days Past AOC Due Date Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/08/2017 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Link (Guarantee) Limited Asia Pacific 11/14/2017 Foregenix Limited 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/29/2017 SecurityMetrics 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

Annual Report Contents

2019 annual report Contents: 1. GLOSSARY 3 2. AT A GLANCE 5 3. BUSINESS MODEL 8 4. CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD’S STATEMENT 10 5. CHAIRPERSON OF THE MANAGEMENT BOARD’S REVIEW 14 6. BOARD OF DIRECTORS 18 7. MANAGEMENT BOARD 23 8. KEY EVENTS 29 9. AWARDS 32 10. MACROECONOMIC AND BANKING REVIEW 34 11. FINANCIAL REVIEW 38 12. BUSINESS REVIEW 42 13. RISK MANAGEMENT 51 14. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 58 15. SOCIAL REPORT 67 16. RESPONSIBILITY STATEMENT 75 17. OUTLOOK 77 18. AUDITED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR 2019 79 (iNCLUDING INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT), NOTES TO THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR 2019 19. INFORMATION FOR SHAREHOLDERS 174 HALYK BANK ANNUAL REPORT 2019 1 glossary 4 Glossary Glossary 1 Altyn Bank Altyn Bank JSC (SB of China Citic Bank Corporation Ltd) 2 AML/CTF Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism 3 BCC Branch credit committee 4 BNCC Branch network credit committee 5 Business Roadmap – 2020 The “Road Map for Business 2020” Unified Programme for Supporting Entrepreneurship and Business Development 6 CITIC Bank China CITIC Bank Corporation Limited 7 GDR Global Depositary Receipt 8 Halyk Bank, the Bank Halyk Bank of Kazakhstan 9 Halyk Group, the Group Halyk Bank Group of Companies 10 IS Information security 11 IT Information technology 12 KASE Kazakhstan Stock Exchange 13 KKB Kazkommertsbank 14 Retail Credit Committee Retail Credit Committee of the Head Bank 15 RK Republic of Kazakhstan 16 SCC Small credit committee of the regional branch 17 SME Small and medium enterprises 18 SPV Special purpose vehicle -

5Ea57a68f19ad.Pdf

A N N U A L R E P O R T 2 0 1 8 CONTENTS 1. GLOSSARY 3 2. AT A GLANCE 5 3. BUSINESS MODEL 11 4. CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD'S STATEMENT 13 5. CHAIRPERSON OF THE MANAGEMENT BOARD'S REVIEW 16 6. BOARD OF DIRECTORS 18 7. MANAGEMENT BOARD 22 8. KEY EVENTS 27 9. AWARDS 31 10. MACROECONOMIC AND BANKING REVIEW 33 11. FINANCIAL REVIEW 37 12. BUSINESS REVIEW 42 13. RISK MANAGEMENT 53 14. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 61 15. SOCIAL REPORT 75 16. RESPONSIBILITY STATEMENT 85 17. OUTLOOK 87 18. AUDITED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR 2018 (INCLUDING INDEPENDENT 90 AUDITORS' REPORT), NOTES TO THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR 2018 19. INFORMATION FOR SHAREHOLDERS 326 2 GLOSSARY GLOSSARY Altyn Bank Altyn Bank JSC (SB of China Citic Bank Corporation Ltd) UAPF Unified Accumulative Pension Fund Halyk Group, the Group Halyk Bank Group of Companies Road Map for Business 2020 The “Road Map for Business 2020” Unified Programme for Supporting Entrepreneurship and Business Development IT Information technology IS Information security SME Small and medium-sized enterprise Halyk Bank, the Bank Halyk Bank of Kazakhstan NBK National Bank of Kazakhstan Halyk Project Halyk Bank's subsidiary for doubtful and bad asset management AML/CFT Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism Damu fund Damu Entrepreneurship Development Fund CITIC Bank China CITIC Bank Corporation Limited GDR Global Depositary Receipt KASE Kazakhstan Stock Exchange 4 2 AT A GLANCE AT A GLANCE FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (CONSOLIDATED BASIS) Key figures 01.01.2019 01.01.2018 Key figures 2018 20172 -

JSC Kazkommertsbank Annual Report for 2016

JSC Kazkommertsbank Annual Report for 2016 July 2017 1 Address of the Management Due to continued complicated macroeconomic situation, devaluation of national currency, changes to regulation and tightened up competition the year 2016 became another ambiguous year for the whole banking sector of Kazakhstan in general and for Kazkommertsbank in particular. Adopted in August 2015 resolution of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan and the National Bank of Kazakhstan on transition to the floating KZT exchange rate to compensate negative implications on the budget driven in turn by downturn of commodity prices resulted into weakening of local currency from KZT187 per US Dollar in August 2015 to KZT310-340 throughout 2016. Banking sector balance sheet demonstrated a substantial excess of FX liabilities vs assets and lack of hedging instruments. This resulted into a sharp growth of exchange rate and subsequent rise in interest expense all over the market. In addition to that, high funding cost and limited liquidity further worsened by outflow of customer accounts away from banking sector, high interest rates on deposits in KZT and lack of access to international capital markets resulted into contraction of lending to real economy. In turn, the rise in cost of funding driven by dried up liquidity in interbank market potentially gives rise to systemic risks, particularly related to ability of market participants to meet taken obligations. Besides, measures undertaken by the National Bank of Kazakhstan to strengthen Kazakhstani financial system led to tightening prudential requirements, particularly requirements on capital adequacy. This put shareholders and founders of banks to decide on additional capital injections. -

Kazakhstan Fall 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

Country Economic Update Kazakhstan Fall 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Kazakhstan The Economy is Rising: Country Economic Update | Fall 2017 It is Still All About Oil Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Macroeconomics & Fiscal Management Global Practice KAZAKHSTAN The Economy is Rising: It is Still All About Oil Country Economic Update Fall 2017 Government Fiscal Year: January 1 – December 31 Currency Unit: Kazakhstani Tenge (KZT) Currency Equivalents: Exchange Rate Effective as of November 1, 2017 US$1 = 334.71 KZT Weights and Measures: Metric System Abbreviations and Acronyms CPSD Country Private Sector Diagnostic EMDEs Emerging market and developing economies FDI Foreign direct investment FX Foreign currency GCI Global Competitiveness Index ICT Information and communication technology NBK National Bank of Kazakhstan NPLs Nonperforming loans PISA Programme for International Student Assessment R&D Research and development SCD Systematic Country Diagnostic SMEs Small and medium enterprises SOEs State-owned enterprises Cover photo credit: / Shutterstock.com: a photo of the Ministry of Energy of Kazakhstan. ii| Table of Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................................................... iv Overview .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Joint Stock Company Kazkommertsbank

JOINT STOCK COMPANY KAZKOMMERTSBANK Interim Condensed Consolidated Financial Information for the six months ended 30 June 2017 (unaudited) Joint Stock Company Kazkommertsbank Table of contents Page STATEMENT OF MANAGEMENT’S RESPONSIBILITIES FOR THE PREPARATION AND APPROVAL OF THE INTERIM CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL INFORMATION FOR THE THREE AND SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2017 (UNAUDITED) 1 REPORT ON REVIEW OF INTERIM CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL INFORMATION 2-3 INTERIM CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL INFORMATION FOR THE THREE AND SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2017 (UNAUDITED): Interim consolidated statement of profit or loss (unaudited) 4 Interim consolidated statement of comprehensive income (unaudited) 5 Interim consolidated statement of financial position (unaudited) 6 Interim consolidated statement of changes in equity (unaudited) 7-8 Interim consolidated statement of cash flows (unaudited) 9-10 Selected explanatory notes to the interim condensed consolidated financial information (unaudited) 11-38 1 REPORT ON REVIEW OF INTERIM FINANCIAL INFORMATION To the Shareholders and the Board of Directors of JSC Kazkommertsbank Introduction We have reviewed the accompanying interim consolidated statement of financial position of JSC Kazkommertsbank (“the Bank”) and its subsidiaries (“the Group”) as at 30 June 2017 and the related interim consolidated statements of profit or loss, and other comprehensive income for the three and six months then ended, and interim consolidated statements of changes in equity and cash flows for the six months then ended, and a summary of significant accounting policies and other explanatory notes. Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of this interim condensed consolidated financial information in accordance with International Accounting Standard (“IAS”) 34, Interim Financial Reporting.