1. LAGRANGIAN MECHANICS 1.1. Hamilton's Principle and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

Relativity with a Preferred Frame. Astrophysical and Cosmological Implications Monday, 21 August 2017 15:30 (30 Minutes)

6th International Conference on New Frontiers in Physics (ICNFP2017) Contribution ID: 1095 Type: Talk Relativity with a preferred frame. Astrophysical and cosmological implications Monday, 21 August 2017 15:30 (30 minutes) The present analysis is motivated by the fact that, although the local Lorentz invariance is one of thecorner- stones of modern physics, cosmologically a preferred system of reference does exist. Modern cosmological models are based on the assumption that there exists a typical (privileged) Lorentz frame, in which the universe appear isotropic to “typical” freely falling observers. The discovery of the cosmic microwave background provided a stronger support to that assumption (it is tacitly assumed that the privileged frame, in which the universe appears isotropic, coincides with the CMB frame). The view, that there exists a preferred frame of reference, seems to unambiguously lead to the abolishmentof the basic principles of the special relativity theory: the principle of relativity and the principle of universality of the speed of light. Correspondingly, the modern versions of experimental tests of special relativity and the “test theories” of special relativity reject those principles and presume that a preferred inertial reference frame, identified with the CMB frame, is the only frame in which the two-way speed of light (the average speed from source to observer and back) is isotropic while it is anisotropic in relatively moving frames. In the present study, the existence of a preferred frame is incorporated into the framework of the special relativity, based on the relativity principle and universality of the (two-way) speed of light, at the expense of the freedom in assigning the one-way speeds of light that exists in special relativity. -

Frames of Reference

Galilean Relativity 1 m/s 3 m/s Q. What is the women velocity? A. With respect to whom? Frames of Reference: A frame of reference is a set of coordinates (for example x, y & z axes) with respect to whom any physical quantity can be determined. Inertial Frames of Reference: - The inertia of a body is the resistance of changing its state of motion. - Uniformly moving reference frames (e.g. those considered at 'rest' or moving with constant velocity in a straight line) are called inertial reference frames. - Special relativity deals only with physics viewed from inertial reference frames. - If we can neglect the effect of the earth’s rotations, a frame of reference fixed in the earth is an inertial reference frame. Galilean Coordinate Transformations: For simplicity: - Let coordinates in both references equal at (t = 0 ). - Use Cartesian coordinate systems. t1 = t2 = 0 t1 = t2 At ( t1 = t2 ) Galilean Coordinate Transformations are: x2= x 1 − vt 1 x1= x 2+ vt 2 or y2= y 1 y1= y 2 z2= z 1 z1= z 2 Recall v is constant, differentiation of above equations gives Galilean velocity Transformations: dx dx dx dx 2 =1 − v 1 =2 − v dt 2 dt 1 dt 1 dt 2 dy dy dy dy 2 = 1 1 = 2 dt dt dt dt 2 1 1 2 dz dz dz dz 2 = 1 1 = 2 and dt2 dt 1 dt 1 dt 2 or v x1= v x 2 + v v x2 =v x1 − v and Similarly, Galilean acceleration Transformations: a2= a 1 Physics before Relativity Classical physics was developed between about 1650 and 1900 based on: * Idealized mechanical models that can be subjected to mathematical analysis and tested against observation. -

Chapter 5 the Relativistic Point Particle

Chapter 5 The Relativistic Point Particle To formulate the dynamics of a system we can write either the equations of motion, or alternatively, an action. In the case of the relativistic point par- ticle, it is rather easy to write the equations of motion. But the action is so physical and geometrical that it is worth pursuing in its own right. More importantly, while it is difficult to guess the equations of motion for the rela- tivistic string, the action is a natural generalization of the relativistic particle action that we will study in this chapter. We conclude with a discussion of the charged relativistic particle. 5.1 Action for a relativistic point particle How can we find the action S that governs the dynamics of a free relativis- tic particle? To get started we first think about units. The action is the Lagrangian integrated over time, so the units of action are just the units of the Lagrangian multiplied by the units of time. The Lagrangian has units of energy, so the units of action are L2 ML2 [S]=M T = . (5.1.1) T 2 T Recall that the action Snr for a free non-relativistic particle is given by the time integral of the kinetic energy: 1 dx S = mv2(t) dt , v2 ≡ v · v, v = . (5.1.2) nr 2 dt 105 106 CHAPTER 5. THE RELATIVISTIC POINT PARTICLE The equation of motion following by Hamilton’s principle is dv =0. (5.1.3) dt The free particle moves with constant velocity and that is the end of the story. -

Branched Hamiltonians and Supersymmetry

Branched Hamiltonians and Supersymmetry Thomas Curtright, University of Miami Wigner 111 seminar, 12 November 2013 Some examples of branched Hamiltonians are explored, as recently advo- cated by Shapere and Wilczek. These are actually cases of switchback poten- tials, albeit in momentum space, as previously analyzed for quasi-Hamiltonian dynamical systems in a classical context. A basic model, with a pair of Hamiltonian branches related by supersymmetry, is considered as an inter- esting illustration, and as stimulation. “It is quite possible ... we may discover that in nature the relation of past and future is so intimate ... that no simple representation of a present may exist.” – R P Feynman Based on work with Cosmas Zachos, Argonne National Laboratory Introduction to the problem In quantum mechanics H = p2 + V (x) (1) is neither more nor less difficult than H = x2 + V (p) (2) by reason of x, p duality, i.e. the Fourier transform: ψ (x) φ (p) ⎫ ⎧ x ⎪ ⎪ +i∂/∂p ⎪ ⇐⇒ ⎪ ⎬⎪ ⎨⎪ i∂/∂x p − ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎭⎪ ⎩⎪ This equivalence of (1) and (2) is manifest in the QMPS formalism, as initiated by Wigner (1932), 1 2ipy/ f (x, p)= dy x + y ρ x y e− π | | − 1 = dk p + k ρ p k e2ixk/ π | | − where x and p are on an equal footing, and where even more general H (x, p) can be considered. See CZ to follow, and other talks at this conference. Or even better, in addition to the excellent books cited at the conclusion of Professor Schleich’s talk yesterday morning, please see our new book on the subject ... Even in classical Hamiltonian mechanics, (1) and (2) are equivalent under a classical canonical transformation on phase space: (x, p) (p, x) ⇐⇒ − But upon transitioning to Lagrangian mechanics, the equivalence between the two theories becomes obscure. -

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM and ROTATIONS

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM AND ROTATIONS In classical mechanics the total angular momentum L~ of an isolated system about any …xed point is conserved. The existence of a conserved vector L~ associated with such a system is itself a consequence of the fact that the associated Hamiltonian (or Lagrangian) is invariant under rotations, i.e., if the coordinates and momenta of the entire system are rotated “rigidly” about some point, the energy of the system is unchanged and, more importantly, is the same function of the dynamical variables as it was before the rotation. Such a circumstance would not apply, e.g., to a system lying in an externally imposed gravitational …eld pointing in some speci…c direction. Thus, the invariance of an isolated system under rotations ultimately arises from the fact that, in the absence of external …elds of this sort, space is isotropic; it behaves the same way in all directions. Not surprisingly, therefore, in quantum mechanics the individual Cartesian com- ponents Li of the total angular momentum operator L~ of an isolated system are also constants of the motion. The di¤erent components of L~ are not, however, compatible quantum observables. Indeed, as we will see the operators representing the components of angular momentum along di¤erent directions do not generally commute with one an- other. Thus, the vector operator L~ is not, strictly speaking, an observable, since it does not have a complete basis of eigenstates (which would have to be simultaneous eigenstates of all of its non-commuting components). This lack of commutivity often seems, at …rst encounter, as somewhat of a nuisance but, in fact, it intimately re‡ects the underlying structure of the three dimensional space in which we are immersed, and has its source in the fact that rotations in three dimensions about di¤erent axes do not commute with one another. -

The Experimental Verdict on Spacetime from Gravity Probe B

The Experimental Verdict on Spacetime from Gravity Probe B James Overduin Abstract Concepts of space and time have been closely connected with matter since the time of the ancient Greeks. The history of these ideas is briefly reviewed, focusing on the debate between “absolute” and “relational” views of space and time and their influence on Einstein’s theory of general relativity, as formulated in the language of four-dimensional spacetime by Minkowski in 1908. After a brief detour through Minkowski’s modern-day legacy in higher dimensions, an overview is given of the current experimental status of general relativity. Gravity Probe B is the first test of this theory to focus on spin, and the first to produce direct and unambiguous detections of the geodetic effect (warped spacetime tugs on a spin- ning gyroscope) and the frame-dragging effect (the spinning earth pulls spacetime around with it). These effects have important implications for astrophysics, cosmol- ogy and the origin of inertia. Philosophically, they might also be viewed as tests of the propositions that spacetime acts on matter (geodetic effect) and that matter acts back on spacetime (frame-dragging effect). 1 Space and Time Before Minkowski The Stoic philosopher Zeno of Elea, author of Zeno’s paradoxes (c. 490-430 BCE), is said to have held that space and time were unreal since they could neither act nor be acted upon by matter [1]. This is perhaps the earliest version of the relational view of space and time, a view whose philosophical fortunes have waxed and waned with the centuries, but which has exercised enormous influence on physics. -

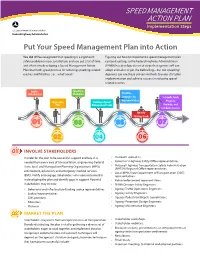

SPEED MANAGEMENT ACTION PLAN Implementation Steps

SPEED MANAGEMENT ACTION PLAN Implementation Steps Put Your Speed Management Plan into Action You did it! You recognized that speeding is a significant Figuring out how to implement a speed management plan safety problem in your jurisdiction, and you put a lot of time can be daunting, so the Federal Highway Administration and effort into developing a Speed Management Action (FHWA) has developed a set of steps that agency staff can Plan that holds great promise for reducing speeding-related adopt and tailor to get the ball rolling—but not speeding! crashes and fatalities. So…what’s next? Agencies can use these proven methods to jump start plan implementation and achieve success in reducing speed- related crashes. Involve Identify a Stakeholders Champion Prioritize Strategies for Set Goals, Track Implementation Market the Develop a Speed Progress, Plan Management Team Evaluate, and Celebrate Success Identify Strategy Leads INVOLVE STAKEHOLDERS In order for the plan to be successful, support and buy-in is • Outreach specialists. needed from every area of transportation: engineering (Federal, • Governor’s Highway Safety Office representatives. State, local, and Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPO), • National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) Regional Office representatives. enforcement, education, and emergency medical services • Local/MPO/State Department of Transportation (DOT) (EMS). Notify and engage stakeholders who were instrumental representatives. in developing the plan and identify gaps in support. Potential • Police/enforcement representatives. stakeholders may include: • FHWA Division Safety Engineers. • Behavioral and infrastructure funding source representatives. • Agency Traffic Operations Engineers. • Judicial representatives. • Agency Safety Engineers. • EMS providers. • Agency Pedestrian/Bicycle Coordinators. • Educators. • Agency Pavement Design Engineers. -

BRST APPROACH to HAMILTONIAN SYSTEMS Our Starting Point Is the Partition Function

BRST APPROACH TO HAMILTONIAN SYSTEMS A.K.Aringazin1, V.V.Arkhipov2, and A.S.Kudusov3 Department of Theoretical Physics Karaganda State University Karaganda 470074 Kazakstan Preprint KSU-DTP-10/96 Abstract BRST formulation of cohomological Hamiltonian mechanics is presented. In the path integral approach, we use the BRST gauge fixing procedure for the partition func- tion with trivial underlying Lagrangian to fix symplectic diffeomorphism invariance. Resulting Lagrangian is BRST and anti-BRST exact and the Liouvillian of classical mechanics is reproduced in the ghost-free sector. The theory can be thought of as a topological phase of Hamiltonian mechanics and is considered as one-dimensional cohomological field theory with the target space a symplectic manifold. Twisted (anti- )BRST symmetry is related to global N = 2 supersymmetry, which is identified with an exterior algebra. Landau-Ginzburg formulation of the associated d = 1, N = 2 model is presented and Slavnov identity is analyzed. We study deformations and per- turbations of the theory. Physical states of the theory and correlation functions of the BRST invariant observables are studied. This approach provides a powerful tool to investigate the properties of Hamiltonian systems. PACS number(s): 02.40.+m, 03.40.-t,03.65.Db, 11.10.Ef, 11.30.Pb. arXiv:hep-th/9811026v1 2 Nov 1998 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1 1 INTRODUCTION Recently, path integral approach to classical mechanics has been developed by Gozzi, Reuter and Thacker in a series of papers[1]-[10]. They used a delta function constraint on phase space variables to satisfy Hamilton’s equation and a sort of Faddeev-Popov representation. -

The Lagrangian and Hamiltonian Mechanical Systems

THE LAGRANGIAN AND HAMILTONIAN MECHANICAL SYSTEMS ALEXANDER TOLISH Abstract. Newton's Laws of Motion, which equate forces with the time- rates of change of momenta, are a convenient way to describe mechanical systems in Euclidean spaces with cartesian coordinates. Unfortunately, the physical world is rarely so cooperative|physicists often explore systems that are neither Euclidean nor cartesian. Different mechanical formalisms, like the Lagrangian and Hamiltonian systems, may be more effective at describing such phenomena, as they are geometric rather than analytic processes. In this paper, I shall construct Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics, prove their equivalence to Newtonian mechanics, and provide examples of both non- Newtonian systems in action. Contents 1. The Calculus of Variations 1 2. Manifold Geometry 3 3. Lagrangian Mechanics 4 4. Two Electric Pendula 4 5. Differential Forms and Symplectic Geometry 6 6. Hamiltonian Mechanics 7 7. The Double Planar Pendulum 9 Acknowledgments 11 References 11 1. The Calculus of Variations Lagrangian mechanics applies physics not only to particles, but to the trajectories of particles. We must therefore study how curves behave under small disturbances or variations. Definition 1.1. Let V be a Banach space. A curve is a continuous map : [t0; t1] ! V: A variation on the curve is some function h of t that creates a new curve +h.A functional is a function from the space of curves to the real numbers. p Example 1.2. Φ( ) = R t1 1 +x _ 2dt, wherex _ = d , is a functional. It expresses t0 dt the length of curve between t0 and t1. Definition 1.3. -

Newtonian Mechanics Is Most Straightforward in Its Formulation and Is Based on Newton’S Second Law

CLASSICAL MECHANICS D. A. Garanin September 30, 2015 1 Introduction Mechanics is part of physics studying motion of material bodies or conditions of their equilibrium. The latter is the subject of statics that is important in engineering. General properties of motion of bodies regardless of the source of motion (in particular, the role of constraints) belong to kinematics. Finally, motion caused by forces or interactions is the subject of dynamics, the biggest and most important part of mechanics. Concerning systems studied, mechanics can be divided into mechanics of material points, mechanics of rigid bodies, mechanics of elastic bodies, and mechanics of fluids: hydro- and aerodynamics. At the core of each of these areas of mechanics is the equation of motion, Newton's second law. Mechanics of material points is described by ordinary differential equations (ODE). One can distinguish between mechanics of one or few bodies and mechanics of many-body systems. Mechanics of rigid bodies is also described by ordinary differential equations, including positions and velocities of their centers and the angles defining their orientation. Mechanics of elastic bodies and fluids (that is, mechanics of continuum) is more compli- cated and described by partial differential equation. In many cases mechanics of continuum is coupled to thermodynamics, especially in aerodynamics. The subject of this course are systems described by ODE, including particles and rigid bodies. There are two limitations on classical mechanics. First, speeds of the objects should be much smaller than the speed of light, v c, otherwise it becomes relativistic mechanics. Second, the bodies should have a sufficiently large mass and/or kinetic energy.