Journey Back in Time—A Mount Rainier Geological Field Trip Guide for Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Itinerary: Mt. Rainier Loop

Itinerary: Mt. Rainier Loop Length: 78 miles Time to Allow: 4-5 hours Open Season: The route is usually snow-free by mid-June and remains open through late October. The road closes each year due to winter snowfall from November to early June. Driving Directions: From Packwood, travel northwest on Forest Road (FR) 52, also called Skate Creek Road, 23 miles to State Route (SR) 706. Turn right on SR 706 and travel east 41.9 miles into Mount Rainier National Park to SR 123. Turn right on SR 123 and travel south 5.4 miles to US Highway 12. Turn right on US Highway 12 and travel 7.3 miles west back to Packwood. Experience the grandeur of Mount Rainier, old-growth temperate rainforest, waterfalls, and impressive vistas! An excellent introduction to Mount Rainier National Park. Start: Begin this mountain adventure in the rural mountain community of Packwood located on Highway 12. Restaurants, car services, lodging, and campgrounds are available. Stop 1: Skate Creek Nestled deep in the forest, watch bubbling Skate Creek as you drive its namesake road. Along this winding, paved, but primitive road, see countless waterfalls cascade along the roadside. See blankets of drooping mosses and experience the beauty and serenity of this little gem. Memorable fall color displays have earned this road the honor of “Best Sunday Drive in Lewis County for Fall Color”. In the wintertime, this road is closed to vehicle traffic and the Skate Creek Sno-Park becomes a popular destination for the snowmobiling crowds. Stop 2: Nisqually Entrance Welcoming visitors to Mount Rainier National Park at the Nisqually Entrance stands a wooden entrance arch built in 1922 and reconstructed in 1973. -

An Inventory of Fish in Streams in Mount Rainier National Park 2001-2003

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science An Inventory of Fish in Streams at Mount Rainier National Park 2001-2003 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2013/717.N ON THE COVER National Park staff conducting a snorkel fish survey in Kotsuck Creek, Mount Rainier National Park, 2002. Photograph courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park. An Inventory of Fish in Streams at Mount Rainier National Park 2001-2003 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2013/717.N Barbara A. Samora, Heather Moran, Rebecca Lofgren National Park Service North Coast and Cascades Network Inventory and Monitoring Program Mount Rainier National Park Tahoma Woods Star Rt. Ashford, WA. 98304 April 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

The Recession of Glaciers in Mount Rainier National Park, Washington

THE RECESSION OF GLACIERS IN MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK, WASHINGTON C. FRANK BROCKMAN Mount Rainier National Park FOREWORD One of the most outstanding features of interest in Mount Rainier National Park is the extensive glacier system which lies, almost entirely, upon the broad flanks of Mount Rainier, the summit of which is 14,408 feet above sea-level. This glacier system, numbering 28 glaciers and aggregating approximately 40-45 square miles of ice, is recognized as the most extensive single peak glacier system in continental United States.' Recession data taken annually over a period of years at the termini of six representative glaciers of varying type and size which are located on different sides of Mount Rainier are indicative of the rela- tive rate of retreat of the entire glacier system here. At the present time the glaciers included in this study are retreating at an average rate of from 22.1 to 70.4 feet per year.2 HISTORY OF INVESTIGATIONS CONDUCTED ON THE GLACIERS OF MOUNT RAINIER Previous to 1900 glacial investigation in this area was combined with general geological reconnaissance surveys on the part of the United States Geological Survey. Thus, the activities of S. F. Em- mons and A. D. Wilson, of the Fortieth Parallel Corps, under Clarence King, was productive of a brief publication dealing in part with the glaciers of Mount Rainier.3 Twenty-six years later, in 1896, another United States Geological Survey party, which included Bailey Willis, I. C. Russell, and George Otis Smith, made additional SCircular of General Information, Mount Rainier National Park (U.S. -

Tolmie State Park Washington State Parks • Park Hours – 7730 61St Ave NE Olympia, WA 98506 April 16 to Sept

Things to remember Tolmie State Park Washington State Parks • Park hours – 7730 61st Ave NE Olympia, WA 98506 April 16 to Sept. 15, (360) 456-6464 8 a.m. to dusk. • Winter schedule – Sept. 16 to State Parks information: (360) 902-8844 April 15, 8 a.m. to dusk, Wednesday through Sunday. Although most parks Reservations: Online at are open year round, some parks or portions of www.parks.state.wa.us or call TolmieState Park parks are closed during the winter. For a winter (888) CAMPOUT or (888) 226-7688 schedule and information about seasonal Other state parks located in closures, visit www.parks.state.wa.us or call the the general area: information center at (360) 902-8844. Eagle Island, Joemma Beach, Millersylvania and Penrose Point • Moorage fees are charged year round for mooring at docks, floats and buoys from 1 p.m. to 8 a.m. • Wildlife, plants and all park buildings, signs, tables and other structures are protected; removal Connect with us on social media or damage of any kind is prohibited. Hunting, www.twitter.com/WAStatePks feeding of wildlife and gathering firewood on state park property is prohibited. www.facebook.com/WashingtonStateParks • Pets must be on leash and under physical control www.youtube.com/WashingtonStateParks at all times. This includes trail areas and campsites. Share your stories and photos: Adventure Awaits.com Pet owners must clean up after pets on all state park lands. S Sample If you would like to support Washington State S Sample Parks even more, please consider making a 2018 donation when renewing your license plate tabs. -

Chambers Creek

Section 3 - Physical and Environmental Inventory 3.1 Chambers Creek – Clover Creek Drainage Basin 3.2 Puyallup River Drainage Basin 3.3 Sewer Service Basins in the Puyallup and White River Drainage Basins 3.4 Nisqually River Drainage Basin 3.5 Kitsap Drainage Basin 3.6 City of Tacoma - North End WWTP 3.7 Joint Base Lewis Mcchord Sewer System – Tatsolo Point WWTP Pierce County Public Works and Utilities – Sewer Utility Unified Sewer Plan Update Section 3 Section 3 – Physical and Environmental Inventory Section 3 documents the land-use and environmental tenants of the four major basins in Pierce County and are organized around those basins. Chambers Creek – Clover Creek Drainage Basin - Section 3.1 Puyallup River Drainage Basin – Section 3.2 Nisqually River Drainage Basin – Section 3.4 Kitsap Drainage Basin – Section 3.5 3.1 Chambers Creek – Clover Creek Drainage Basin The Chambers Creek - Clover Creek Drainage Basin (Basin) is located in central Pierce County, between Puget Sound on the west and the ridge above the Puyallup River Valley on the east. Point Defiance and the southwest shore of Commencement Bay serve as the basin’s northern boundary, and the City of DuPont lies on the southern boundary. The basin encompasses approximately 104,258 acres (117 square miles) of land including the Cities of DuPont, including Northwest Landing, University Place, Lakewood, and Northwest Tacoma, Fircrest, the Towns of Ruston, and Steilacoom, as well as portions of Fort Lewis and McChord Military Reservations, and the unincorporated communities of South Hill, Frederickson, Mid County, Graham, Parkland, and Spanaway. 3.1.1 Topography Lowland topography is generally flat to gently rolling. -

Evidence of a Changing Climate Impacting the Fluvial Geomorphology of the Kautz Creek on Mt

EVIDENCE OF A CHANGING CLIMATE IMPACTING THE FLUVIAL GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE KAUTZ CREEK ON MT. RAINIER by Melanie R. Graeff A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Environmental Studies The Evergreen State College June, 2017 ©2017 by Melanie R. Graeff. All rights reserved. This Thesis for the Master of Environmental Studies Degree by Melanie R. Graeff has been approved for The Evergreen State College by ________________________ Michael Ruth, M.Sc Member of the Faculty ________________________ Date ABSTRACT Evidence of a Changing Climate Impacting the Fluvial Geomorphology of the Kautz Creek on Mt. Rainier Melanie Graeff Carbon dioxide emissions have stimulated the warming of air and ocean temperatures worldwide. These conditions have fueled the intensity of El Nino-Southern Oscillation and Atmospheric River events by supplying increased water vapor into the atmosphere. These precipitation events have impacted the fluvial geomorphology of a creek on the southwestern flank of the Kautz Creek on Mt. Rainier, Washington. Using GIS software was the primary means of obtaining data due to the lack of publications published on the Kautz Creek. Time periods of study were set up from a 2012 publication written by Jonathan Czuba and others, that mentioned observations of the creek that dated from 1960 to 2008. In combining those observations of the Kautz and weather data from the weather station in Longmire, Washington, this allowed for a further understanding of how climate change has affected the fluvial geomorphology of the Kautz Creek over time. GIS software mapping showed numerous changes on the creek since 2008. -

Chapter 13 -- Puget Sound, Washington

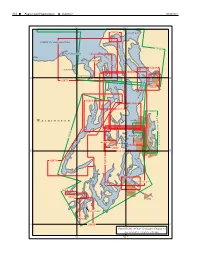

514 Puget Sound, Washington Volume 7 WK50/2011 123° 122°30' 18428 SKAGIT BAY STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA S A R A T O 18423 G A D A M DUNGENESS BAY I P 18464 R A A L S T S Y A G Port Townsend I E N L E T 18443 SEQUIM BAY 18473 DISCOVERY BAY 48° 48° 18471 D Everett N U O S 18444 N O I S S E S S O P 18458 18446 Y 18477 A 18447 B B L O A B K A Seattle W E D W A S H I N ELLIOTT BAY G 18445 T O L Bremerton Port Orchard N A N 18450 A 18452 C 47° 47° 30' 18449 30' D O O E A H S 18476 T P 18474 A S S A G E T E L N 18453 I E S C COMMENCEMENT BAY A A C R R I N L E Shelton T Tacoma 18457 Puyallup BUDD INLET Olympia 47° 18456 47° General Index of Chart Coverage in Chapter 13 (see catalog for complete coverage) 123° 122°30' WK50/2011 Chapter 13 Puget Sound, Washington 515 Puget Sound, Washington (1) This chapter describes Puget Sound and its nu- (6) Other services offered by the Marine Exchange in- merous inlets, bays, and passages, and the waters of clude a daily newsletter about future marine traffic in Hood Canal, Lake Union, and Lake Washington. Also the Puget Sound area, communication services, and a discussed are the ports of Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, and variety of coordinative and statistical information. -

1934 the MOUNTAINEERS Incorpora.Ted T�E MOUNTAINEER VOLUME TWENTY-SEVEN Number One

THE MOUNTAINEER VOLUME TWENTY -SEVEN Nom1-0ae Deceml.er, 19.34 GOING TO GLACIER PUBLISHED BY THE MOUNTAIN�ER.S INCOaPOllATBD SEATTLI: WASHINGTON. _,. Copyright 1934 THE MOUNTAINEERS Incorpora.ted T�e MOUNTAINEER VOLUME TWENTY-SEVEN Number One December, 1934 GOING TO GLACIER 7 •Organized 1906 Incorporated 1913 EDITORIAL BOARD, 1934 Phyllis Young Katharine A. Anderson C. F. Todd Marjorie Gregg Arthur R. Winder Subscription Price, $2.00 a Year Annual (only) Seventy-five Cents Published by THE MOUNTAINEERS Incorporated Seattle, Washington Entered as second class matter, December 15, 1920, at the Postofflce at Seattle, Washington, under the Act of March 3, 1879. TABLE OF CONTENTS Greeting ........................................................................Henr y S. Han, Jr. North Face of Mount Rainier ................................................ Wolf Baiter 3 r Going to Glacier, Illustrated ............... -.................... .Har iet K. Walker 6 Members of the 1934 Summer Outing........................................................ 8 The Lake Chelan Region ............. .N. W. <J1·igg and Arthiir R. Winder 11 Map and Illustration The Climb of Foraker, Illitstrated.................................... <J. S. Houston 17 Ascent of Spire Peak ............................................... -.. .Kenneth Chapman 18 Paradise to White River Camp on Skis .......................... Otto P. Strizek 20 Glacier Recession Studies ................................................H. Strandberg 22 The Mounta,ineer Climbers................................................ -

Mount Rainier National Park, Washington

NATIONAL PARK . WASHINGTON MOUNT RAINIER WASHINGTON CONTENTS "The Mountain" 1 Wealth of Gorgeous Flowers 3 The Forests 5 How To Reach the Park 8 By Automobile 8 By Railroad and Bus 11 By Airplane 11 Administration 11 Free Public Campgrounds 11 Post Offices 12 Communication and Express Service 12 Medical Service 12 Gasoline Service 12 What To Wear 12 Trails 13 Fishing 13 Mount Rainier Summit Climb 13 Accommodations and Expenses 15 Summer Season 18 Winter Season 18 Ohanapecosh Hot Springs 20 Horseback Trips and Guide Service 20 Transportation 21 Tables of Distances 23 Principal Points of Interest 28 References 32 Rules and Regulations 33 Events of Historical Importance 34 Government Publications 35 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • Harold L. Ickes, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammerer, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE • 1938 AN ALL-YEAR PARK Museums.—The park museum, headquarters for educational activities, MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK may be fully enjoyed throughout the and office of the park naturalist are located in the museum building at year. The summer season extends from early June to early November; the Longmire. Natural history displays and wild flower exhibits are main winter ski season, from late November well into May. All-year roads make tained at Paradise Community House, Yakima Park Blockhouse, and the park always accessible. Longmire Museum. Nisquaiiy Road is open to Paradise Valley throughout the year. During Hikes from Longmire.—Free hikes, requiring 1 day for the round trip the winter months this road is open to general traffic to Narada Falls, 1.5 are conducted by ranger naturalists from the museum to Van Trump Park, miles by trail from Paradise Valley. -

Shoreline Inventory and Characterization Report

Final Draft THURSTON COUNTY SHORELINE MASTER PROGRAM UPDATE Inventory and Characterization Report SMA Grant Agreements: G0800104 and G1300026 June 30, 2013 Prepared By: Thurston County Planning Department Building # 1, 2nd Floor 2000 Lakeridge Drive SW Olympia, WA 98502-6045 This page left intentionally blank. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 1 REPORT PURPOSE .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 SHORELINE MASTER PROGRAM UPDATES FOR CITIES WITHIN THURSTON COUNTY ...................................................................... 2 REGULATORY OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................. 2 SHORELINE JURISDICTION AND DEFINITIONS ........................................................................................................................ 3 REPORT ORGANIZATION .................................................................................................................................................. 5 2 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 DETERMINING SHORELINE JURISDICTION LIMITS .................................................................................................................. -

An Early Warning Program for Harmful Algal Blooms in Puget Sound

An Early Warning Program for Harmful Algal Blooms in Puget Sound Harmful Algae Puget Sound is one of the most naturally beautiful and ecologically diverse locations in the Pacific Northwest. However, these waters are home to several species of algae that can produce deadly toxins when water conditions encourage their populations to explode. During these harmful algal blooms (HABs), the algae and their toxins accumulate in shellfish, and are also transferred up the food chain to marine and terrestrial animals. High concentrations of some algal species can sicken or kill marine birds, mammals or humans and can cause fish to die in large numbers. The SoundToxins program We formed SoundToxins—the Partnership for Enhanced Monitoring and Emergency Response to HABs in Puget Sound—to combat the apparent increase in these HAB occurrences over the past decade. SoundToxins is a diverse partnership of shellfish farmers, fish farmers, environmental learning centers, volunteers, local health jurisdictions, colleges, and Native American tribes that was conceived and initiated by Northwest Fisheries Science Center (NWFSC), and is now co- directed by Washington Sea Grant (WSG). SoundToxins has grown from four partners in 2006 to over 28 partners in 2017, some of whom monitor multiple sites in Puget Sound. SoundToxins has three main objectives: • To document unusual bloom events and new species entering Puget Sound. • To determine the environmental conditions that promote the onset and flourishing of HABs. • To determine the combination of monitoring parameters that provide the earliest warnings of these events. Monitoring Puget Sound Pseudo-nitzschia SoundToxins samples phytoplankton, These algae are pennate diatoms that can produce a or single-celled algae, throughout toxin called domoic acid. -

Magnificent Mt. Rainier

RV Traveler's Roadmap to Mt. Rainer Ascending to 14,410 feet above sea level, Mount Rainier stands as an icon in the Washington landscape. An active volcano, Mount Rainier is the most glaciated peak in the contiguous U.S.A., spawning six major rivers. Sub alpine wildflower meadows ring the icy volcano while ancient forest cloaks Mount Rainier’s lower slopes. Wildlife abounds in the park’s ecosystems. A lifetime of discovery awaits. 1 Highlights & Facts For The Ideal Experience Mt. Rainier National Park Trip Length: Roughly 220 miles Visitors Centers: Longmire, Paradise, Ohanapecosh, Sunrise Best Time To Go: Summer for wildflowers, early fall for foliage and less visitors. Parks roads are closed from November - April except Nisqually/Paradise Supply Location: Longmire 2 Traveler's Notes Lake Mayfield, WA. Roughly an hours drive from Mt. Rainier Year-round access to the park is via SR 706 to the Nisqually Entrance in the southwest corner of the park. The road from the entrance to Longmire remains open throughout winter except during extreme weather. The highly visible Columbian black-tailed deer, Douglas squirrels, noisy Stellar's jays and common ravens are animals that many people remember. The most diverse and abundant animals in the park, however, are the invertebrates - the insects, worms, crustaceans, spiders- to name a few - that occupy all environments to the top of Columbia Crest itself. Every summer thousands of hikers and backpackers travel to Mount Rainier National Park to make a trip along the Wonderland Trail, seeking the same scenic splendors and thrilling adventures that Superintendent Roger Toll described above.