Voyages of Discovery in the 18Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lonely Island

The Lonely Island By R. M. Ballantyne The Lonely Island Chapter One. The Refuge of the Mutineers. The Mutiny. On a profoundly calm and most beautiful evening towards the end of the last century, a ship lay becalmed on the fair bosom of the Pacific Ocean. Although there was nothing piratical in the aspect of the shipif we except her gunsa few of the men who formed her crew might have been easily mistaken for roving buccaneers. There was a certain swagger in the gait of some, and a sulky defiance on the brow of others, which told powerfully of discontent from some cause or other, and suggested the idea that the peaceful aspect of the sleeping sea was by no means reflected in the breasts of the men. They were all British seamen, but displayed at that time none of the wellknown hearty offhand rollicking characteristics of the Jacktar. It is natural for man to rejoice in sunshine. His sympathy with cats in this respect is profound and universal. Not less deep and wide is his discord with the moles and bats. Nevertheless, there was scarcely a man on board of that ship on the evening in question who vouchsafed even a passing glance at a sunset which was marked by unwonted splendour. The vessel slowly rose and sank on a scarce perceptible oceanswell in the centre of a great circular field of liquid glass, on whose undulations the sun gleamed in dazzling flashes, and in whose depths were reflected the fantastic forms, snowy lights, and pearly shadows of cloudland. -

(Mutiny on the Bounty, 1935) És Una Pel·Lícula Norda

La legendària rebel·lió a bord de la Bounty La tragèdia de la Bounty (Mutiny on the Bounty , 1935) és una pel·lícula nordamericana, dirigida per Frank Lloyd, i interpretada per Clarck Gable i Charles Laughton, que relata la història de l'amotinament dels mariners de la Bounty . El 28 d'abril de 1789, 31 dels 46 homes del veler de l'armada britànica Bounty s'amotinaren. L'oficial Fletcher Christian encapçalà l'amotinament contra el comandant de la nau, el tinent William Bligh, un marí amb experiència, que havia acompanyat Cook en el seu tercer viatge al Pacífic. La nau havia marxat a la Polinèsia per tal d'arreplegar especímens de l'arbre del pa, per tal de dur-los al Carib, perquè els seus fruits, rics en glúcids, serviren d'aliment als esclaus. El 26 d'octubre de 1788 ja havien carregat 1015 exemplars de l'arbre. En començar el viatge de tornada es va produir l'amotinament i els mariners llançaren els arbres al mar. Bligh i 18 homes foren abandonats en un bot. En 1790, després de 6.000 km de navegació heròica, arribaren a Gran Bretanya. L'armada britànica envià un vaixell per reprimir el motí, el Pandora , comandat per Erward Edwards. Va matar 4 amotinats. Per haver perdut la nau, Bligh va patir un consell de guerra. En 1804 fou governador de Nova Gal·les del Sud (Austràlia) i la seua repressió del comerç de rom provocà una revolta. L'única colònia britànica que queda en el Pacífic són les illes Pitcairn. Els seus 50 habitants (dades 2010) viuen en la major de les illes, de 47 km 2. -

Commercial Enterprise and the Trader's Dilemma on Wallis

Between Gifts and Commodities: Commercial Enterprise and the Trader’s Dilemma on Wallis (‘Uvea) Paul van der Grijp Toa abandoned all forms of gardening, obtained a loan, and built a big shed to house six thousand infant chickens flown in from New Zealand. The chickens grew large and lovely, and Toa’s fame spread. Everyone knew he had six thousand chickens and everyone wanted to taste them. A well-bred tikong gives generously to his relatives and neighbours, especially one with thousands of earthly goods. But . Toa aimed to become a Modern Busi- nessman, forgetting that in Tiko if you give less you will lose more and if you give nothing you will lose all. epeli hau‘ofa, the tower of babel Recently, the model of the trader’s dilemma was developed as an ana- lytical perspective and applied to Southeast Asia. The present paper seeks to apply this model in Western Polynesia, where many Islanders, after earning wages in Australia, New Zealand, the United States, or New Cale- donia, return to open a small shop in their home village. Usually, after one or two years of generous sharing, such enterprises have to close down. I analyze this phenomenon through case studies of successful indigenous entrepreneurs on Wallis (‘Uvea), with special attention to strategies they have used to cope with this dilemma. The Paradigm of the Trader’s Dilemma The trader’s dilemma is the quandary between the moral obligation to share wealth with kinfolk and neighbors and the necessity to make a profit and accumulate capital. Western scholars have recognized this dilemma The Contemporary Pacific, Volume 15, Number 2, Fall 2003, 277–307 © 2003 by University of Hawai‘i Press 277 278 the contemporary pacific • fall 2003 since the first fieldwork in economic anthropology by Bronislaw Malinow- ski (1922), Raymond Firth (1929; 1939), and others. -

Captain Bligh's Second Voyage to the South Sea

Captain Bligh's Second Voyage to the South Sea By Ida Lee Captain Bligh's Second Voyage To The South Sea CHAPTER I. THE SHIPS LEAVE ENGLAND. On Wednesday, August 3rd, 1791, Captain Bligh left England for the second time in search of the breadfruit. The "Providence" and the "Assistant" sailed from Spithead in fine weather, the wind being fair and the sea calm. As they passed down the Channel the Portland Lights were visible on the 4th, and on the following day the land about the Start. Here an English frigate standing after them proved to be H.M.S. "Winchelsea" bound for Plymouth, and those on board the "Providence" and "Assistant" sent off their last shore letters by the King's ship. A strange sail was sighted on the 9th which soon afterwards hoisted Dutch colours, and on the loth a Swedish brig passed them on her way from Alicante to Gothenburg. Black clouds hung above the horizon throughout the next day threatening a storm which burst over the ships on the 12th, with thunder and very vivid lightning. When it had abated a spell of fine weather set in and good progress was made by both vessels. Another ship was seen on the 15th, and after the "Providence" had fired a gun to bring her to, was found to be a Portuguese schooner making for Cork. On this day "to encourage the people to be alert in executing their duty and to keep them in good health," Captain Bligh ordered them "to keep three watches, but the master himself to keep none so as to be ready for all calls". -

The William F. Charters South Seas Collection at Butler University: a Selected, Annotated Catalogue (1994)

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Special Collections Bibliographies University Special Collections 1994 The William F. Charters South Seas Collection at Butler University: A Selected, Annotated Catalogue (1994) Gisela S. Terrell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/scbib Part of the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Terrell, Gisela S., "The William F. Charters South Seas Collection at Butler University: A Selected, Annotated Catalogue (1994)" (1994). Special Collections Bibliographies. 5. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/scbib/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE WILLIAM F. CHARTERS SOUTH SEAS COLLECTION The Irwin Library Butler University Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/williamfchartersOOgise The William F. Charters South Seas Collection at Butler University A Selected, Annotated Catalogue By Gisela Schluter Terrell With an Introduction By George W. Geib 1994 Rare Books & Special Collections Irwin Library Butler University Indianapolis, Indiana ©1994 Gisela Schluter Terrell 650 copies printed oo recycled paper Printed on acid-free, (J) Rare Books & Special Collections Irwin Library Butler University 4600 Sunset Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana 46208 317/283-9265 Produced by Butler University Publications Dedicated to Josiah Q. Bennett (Bookman) and Edwin J. Goss (Bibliophile) From 1972 to 1979, 1 worked as cataloguer at The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington. Much of what I know today about the history of books and printing was taught to me by Josiah Q. -

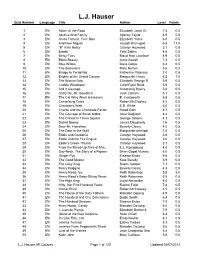

AR Quizzes for L.J. Hauser

L.J. Hauser Quiz Number Language Title Author Level Points 1 EN Adam of the Road Elizabeth Janet Gr 7.4 0.5 2 EN All-of-a-Kind Family Sydney Taylor 4.9 0.5 3 EN Amos Fortune, Free Man Elizabeth Yates 6.0 0.5 4 EN And Now Miguel Joseph Krumgold 6.8 11.0 5 EN "B" is for Betsy Carolyn Haywood 3.1 0.5 6 EN Bambi Felix Salten 4.6 0.5 7 EN Betsy-Tacy Maud Hart Lovelace 4.9 0.5 8 EN Black Beauty Anna Sewell 7.3 0.5 9 EN Blue Willow Doris Gates 6.4 0.5 10 EN The Borrowers Mary Norton 5.6 0.5 11 EN Bridge to Terabithia Katherine Paterson 7.0 0.5 12 EN Brighty of the Grand Canyon Marguerite Henry 6.2 7.0 13 EN The Bronze Bow Elizabeth George S 5.9 0.5 14 EN Caddie Woodlawn Carol Ryrie Brink 5.6 0.5 15 EN Call It Courage Armstrong Sperry 5.0 0.5 16 EN Carry On, Mr. Bowditch Jean Latham 5.1 0.5 17 EN The Cat Who Went to Heaven E. Coatsworth 5.8 0.5 18 EN Centerburg Tales Robert McCloskey 5.2 0.5 19 EN Charlotte's Web E.B. White 6.0 0.5 20 EN Charlie and the Chocolate Factor Roald Dahl 6.7 0.5 21 EN The Courage of Sarah Noble Alice Dalgliesh 4.2 0.5 22 EN The Cricket in Times Square George Selden 4.3 0.5 23 EN Daniel Boone James Daugherty 7.6 0.5 24 EN Dear Mr. -

Adult Trade January-June 2018

BLOOMSBURY January – June 2018 NEW TITLES January – June 2018 2 Original Fiction 12 Paperback Fiction 26 Crime, Thriller & Mystery 32 Paperback Crime, Thriller & Mystery 34 Original Non-Fiction 68 Food 78 Wellbeing 83 Popular Science 87 Nature Writing & Outdoors 92 Religion 93 Sport 99 Business 102 Maritime 104 Paperback Non-fiction 128 Bloomsbury Contact List & International Sales 131 Social Media Contacts 132 Index export information TPB Trade Paperback PAPERBACK B format paperback (dimensions 198 mm x 129 mm) Peach Emma Glass Introducing a visionary new literary voice – a novel as poetic as it is playful, as bold as it is strangely beautiful omething has happened to Peach. Blood runs down her legs Sand the scent of charred meat lingers on her flesh. It hurts to walk but she staggers home to parents that don’t seem to notice. They can’t keep their hands off each other and, besides, they have a new infant, sweet and wobbly as a jelly baby. Peach must patch herself up alone so she can go to college and see her boyfriend, Green. But sleeping is hard when she is haunted by the gaping memory of a mouth, and working is hard when burning sausage fat fills her nostrils, and eating is impossible when her stomach is swollen tight as a drum. In this dazzling debut, Emma Glass articulates the unspeakable with breathtaking clarity and verve. Intensely physical, with rhythmic, visceral prose, Peach marks the arrival of a ground- breaking new talent. 11 JANUARY 2018 HARDBACK • 9781408886694 • £12.99 ‘An immensely talented young writer . Her fearlessness renews EBOOK • 9781408886670 • £10.99 one’s faith in the power of literature’ ANZ PUB DATE 01 FEBRUARY 2018 George Saunders HARDBACK • AUS $24.99 • NZ $26.99 TERRITORY: WO ‘You'll be unable to put it down until the very last sentence’ TRANSLATION RIGHTS: BLOOMSBURY Kamila Shamsie ‘Peach is a work of genius. -

Bounty Saga Articles Bibliography

Bounty Saga Articles Bibliography By Gary Shearer, Curator, Pitcairn Islands Study Center "1848 Watercolours." Pitcairn Log 9 (June 1982): 10-11. Illus in b&w. "400 Visitors Join 50 Members." Australasian Record 88 (July 30,1983): 10. "Accident Off Pitcairn." Australasian Record 65 (June 5,1961): 3. Letter from Mrs. Don Davies. Adams, Alan. "The Adams Family: In The Wake of the Bounty." The UK Log Number 22 (July 2001): 16-18. Illus. Adams, Else Jemima (Obituary). Australasian Record 77 (October 22,1973): 14. Died on Norfolk Island. Adams, Gilbert Brightman (Obituary). Australasian Record 32 (October 22,1928): 7. Died on Norfolk Island. Adams, Hager (Obituary). Australasian Record 26 (April 17,1922): 5. Died on Norfolk Island. Adams, M. and M. R. "News From Pitcairn." Australasian Record 19 (July 12,1915): 5-6. Adams, M. R. "A Long Isolation Broken." Australasian Record 21 (June 4,1917): 2. Photo of "The Messenger," built on Pitcairn Island. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (April 30,1956): 2. Illus. Story of Miriam and her husband who labored on Pitcairn beginning in December 1911 or a little later. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 7,1956): 2-3. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 14,1956): 2-3. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 21,1956): 2. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 28,1956): 2. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (June 4,1956): 2. Adams, Miriam. "Letter From Pitcairn Island." Review & Herald 91 (Harvest Ingathering Number,1914): 24-25. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography

THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY VOLUME CXXXVI October 2012 NO. 4 EDITORIAL Tamara Gaskell 329 INTRODUCTION Daniel P. Barr 331 REVIEW ESSAY:DID PENNSYLVANIA HAVE A MIDDLE GROUND? EXAMINING INDIAN-WHITE RELATIONS ON THE EIGHTEENTH- CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA FRONTIER Daniel P. Barr 337 THE CONOJOCULAR WAR:THE POLITICS OF COLONIAL COMPETITION, 1732–1737 Patrick Spero 365 “FAIR PLAY HAS ENTIRELY CEASED, AND LAW HAS TAKEN ITS PLACE”: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE SQUATTER REPUBLIC IN THE WEST BRANCH VALLEY OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER, 1768–1800 Marcus Gallo 405 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS:A CUNNING MAN’S LEGACY:THE PAPERS OF SAMUEL WALLIS (1736–1798) David W. Maxey 435 HIDDEN GEMS THE MAP THAT REVEALS THE DECEPTION OF THE 1737 WALKING PURCHASE Steven C. Harper 457 CHARTING THE COLONIAL BACKCOUNTRY:JOSEPH SHIPPEN’S MAP OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER Katherine Faull 461 JOHN HARRIS,HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION, AND THE STANDING STONE MYSTERY REVEALED Linda A. Ries 466 REV.JOHN ELDER AND IDENTITY IN THE PENNSYLVANIA BACKCOUNTRY Kevin Yeager 470 A FAILED PEACE:THE FRIENDLY ASSOCIATION AND THE PENNSYLVANIA BACKCOUNTRY DURING THE SEVEN YEARS’WAR Michael Goode 472 LETTERS TO FARMERS IN PENNSYLVANIA:JOHN DICKINSON WRITES TO THE PAXTON BOYS Jane E. Calvert 475 THE KITTANNING DESTROYED MEDAL Brandon C. Downing 478 PENNSYLVANIA’S WARRANTEE TOWNSHIP MAPS Pat Speth Sherman 482 JOSEPH PRIESTLEY HOUSE Patricia Likos Ricci 485 EZECHIEL SANGMEISTER’S WAY OF LIFE IN GREATER PENNSYLVANIA Elizabeth Lewis Pardoe 488 JOHN MCMILLAN’S JOURNAL:PRESBYTERIAN SACRAMENTAL OCCASIONS AND THE SECOND GREAT AWAKENING James L. Gorman 492 AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY LINGUISTIC BORDERLAND Sean P. -

Tahiti & French Polynesia

READING GUIDE TAHITI & FRENCH POLYNESIA ere is a brief selection of favorite, new and hard-to-find books, prepared for your journey. For your convenience, you may call (800) 342-2164 to order these books directly from Longitude, a specialty mail- Horder book service. To order online, and to get the latest, most comprehensive selection of books for your voyage, go directly to reading.longitudebooks.com/D924803. ITMB ESSENTIAL Tahiti Travel Reference Map 2008, MAP, PAGES, $12.95 Item EXPAC259. Buy these 5 items as a set for $76 A detailed traveler’s map (1:100,000) of including shipping, 15% off the retail price. With free Tahiti and nearby Society Islands, including shipping on anything else you order. Bora Bora, Moorea, Tahaa and Raiatea. (Item Paul Theroux PAC326) The Happy Isles of Oceania 2006, PAPER, 480 PAGES, $16.95 ALSO RECOMMENDED The peripatetic author flies off to Australia and New Zealand with a kayak and ends up Lonely Planet exploring much of Melanesia and Polynesia, Lonely Planet South Pacific including Tonga, Fiji and the Marquesas, in this wickedly funny, wide-ranging tale. (Item Phrasebook PAC03) 2008, PAPER, 320 PAGES, $8.99 This handy pocket phrasebook covers the Paul Gauguin, John Miller (Editor) languages of the Cook Islands, Easter Island, Noa Noa, The Tahiti Journal Fiji, Hawaii, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Norfolk & Pitcairn islands, Samoa, Tahiti 1985, PAPER, 96 PAGES, $5.95 Gauguin’s impressions of two years in French and Tonga. (Item PAC224) Polynesia, originally published in 1919. With 24 Anne Salmond black-and-white illustrations. (Item PAC13) Aphrodite’s Island, The European Discovery of Tahiti Paddy Ryan 2010, HARD COVER, 537 PAGES, $47.95 The Snorkeller’s Guide to the Coral Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, James Cook, Reef, From the Red Sea to the Pacific Samuel Wallis and many more early European Ocean voyagers join local heroes, Tahitian warriors 1994, PAPER, 184 PAGES, $21.99 and kings in this authoritative, richly detailed This take-along guide covers coral reefs, fish, history of French Polynesia and its allure. -

Putting Down Roots Belonging and the Politics of Settlement on Norfolk Island

Putting Down Roots Belonging and the Politics of Settlement on Norfolk Island Mitchell Kenneth Low B.A. (Hons) University of Western Australia, 2004 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences (Anthropology and Sociology) 2012 Abstract In this thesis I theorise emergent nativeness and the political significance of resettlement among the descendants of the mutineers of the Bounty in the Australian external territory of Norfolk Island (South Pacific). Norfolk Islanders are a group of Anglo-Polynesian descendants who trace their ancestry to unions between the mutineers of the HMAV Bounty and Tahitian women. Norfolk Islanders’ ancestors were resettled from their home of Pitcairn Island to the decommissioned, vacant, penal settlement of Norfolk Island in 1856. Since this date, members of the Norfolk community have remained at odds with state officials from Britain and Australia over the exact nature of their occupancy of Norfolk Island. This fundamental contestation over the Island’s past is the basis of ongoing struggles over recognition, Island autonomy and territoriality, and belonging. Using a combination of qualitative research conducted on Norfolk Island and extensive historical and archival research, I present an ethnography of belonging among a highly emplaced island population. One of the central problems in conceptualising Norfolk Islanders’ assertions of belonging is that Norfolk Islanders not only claim Norfolk as a homeland, but members of this community have at times declared themselves the indigenous people of the Island. With respect to recent anthropological theorisations of indigeneity as relationally and historically constituted, I consider the extent to which concepts such as ‘native’ and ‘indigenous’ may be applicable to descendants of historical migrants. -

Tupaia: Master Navigator

School Journal Go to www.schooljournal.tki.org.nz for PDFs of all the texts in this issue of the School Journal as Tupaia: Master Navigator Level 3, August 2019 well as teacher support material (TSM) for the following: TSM School Trespass Instructions for Travelling without Touching by Hanahiva Rose Year 6 the Ground Journal Tupaia: Master Navigator AUGUST 2019 AUGUST August SCHOOL JOURNAL 2019 Overview This TSM contains information and suggestions for teachers to pick and choose from, depending on the needs of their students and their purpose for using the text. The materials provide many opportunities for revisiting the text. Tupaia was a Tahitian navigator and high-priest who travelled to Aotearoa ▪ broadens the historical narratives about with Captain Cook and the crew of the Endeavour in 1769. Tupaia spoke many first encounters between Māori and the British languages and played a crucial role mediating between Māori and the British ▪ contains words and phrases in te reo Māori, reo māohi (a language spoken in the first formal encounters between the two peoples. He was recognised by in Tahiti), and English tangata whenua as a person of great mana. Although his significant contribution to Cook’s journey has generally been overlooked, Tupaia is remembered in ▪ contrasts the way Tupaia was acknowledged and remembered by Māori Māori oral histories and remains a key figure in the history of Aotearoa. with the way he was treated by the crew of the Endeavour This story: ▪ emphasises important links between Polynesian and Māori cultures, for The ‘arioi were based at Taputapuātea. This great marae was at the centre example, a common language base and a shared ancestral homeland ▪ recounts the story of Tupaia, an important Tahitian navigator who Hawai‘iHawai‘i of a large group of islands and home to the temple of ‘Oro.