Strasbourg, 4 June 1993 - 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acs Courier Network (Cyprus)

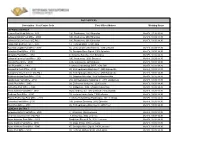

4.2021 ACS COURIER NETWORK (CYPRUS) SERVICE POINT AREA ADDRESS TELEPHONE OPENING HOURS City Centre - N8 1C Evagorou Ave & An.Leventi, 1097 Nicosia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 8:45-18:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Michalakopoulou - N3 22 Michalacopoulou Str, 1075 Nicosia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Strovolos - N2 70 Athalassas Ave, 2012 Strovolos 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Engomi - EG 34B October 28th Str, 2414 Engomi 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Lakatamia - LK 40H Makariou Ave, 2324 Lakatamia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Strakka - N9 351 Arch. Makariou III, 2313 Pano Lakatamia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-18:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Pallouriotisa - N6 68A John Kennedy Ave, 1046 Pallouriotisa 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-18:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Pera Chorio Nisou- PR 27C Makariou Ave, 2572 Pera Chorio Nisou 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-18:00 Sat: 8:45-13:00 Strovolos Ind.Area - N5 14 Varkizas Str, 2033 Strovolos Ind. Area 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 07:45 - 19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 NICOSIA Latsia - LA 33 Arch. Makariou Ave, 2220 Latsia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Kokkinotrimithia - KR 2 Gr. Auxentiou & Avlonos 2660 Kokkinotrimithia 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-18:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Astromeritis - N7 70A Grivas Digenis Ave, 2722 Astromeritis 99 465150 Mon-Fri 10:00 - 19:00 Sat 08:00-13:00 Soleas area- SL 47 Makariou Str, 2800 Kakopetria 22 922219 Mon-Fri 10:30-13:00+15:15-17:30 Wed + Sat 10:30-13:00 Ergates - ER 2 Meg.Alexandrou, 2643 Ergates 22 515155 Mon-Fri 9:00-18:00 Wed + Sat 9:00-14:00 Tsireio - L4 41 Stelios Kyriakides Str, 3080 Limassol 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Agios Nicolaos - L2 3 Riga Feraiou Str, 3095 Limassol 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Omonoia - ΟΜ 35A Vasileos Pavlou Str, 3052 Limassol 7777 7373 Mon-Fri 7:45-19:00 Sat 8:45-13:00 Kolonakiou - LF 17 Sp. -

Larnaka Gastronomy Establishments

Catering and Entertainment Establishments for LARNAKA 01/02/2019 Category: RESTAURANT Name Address Telephone Category/ies 313 SMOKE HOUSE 57, GRIGORI AFXENTIOU STREET, AKADEMIA CENTER 99617129 RESTAURANT 6023, LARNACA 36 BAY STREET 56, ATHINON AVENUE, 6026, LARNACA 24621000 & 99669123 RESTAURANT, PUB 4 FRIENDS 5, NIKIFOROU FOKA STREET, 6021, LARNACA 96868616 RESTAURANT A 33 GRILL & MEZE RESTAURANT 33, AIGIPTOU STREET, 6030, LARNACA 70006933 & 99208855 RESTAURANT A. & K. MAVRIS CHICKEN LODGE 58C, ARCH. MAKARIOU C' AVENUE, 6017, LARNACA 24-651933, 99440543 RESTAURANT AKROYIALI BEACH RESTAURANT MAZOTOS BEACH, 7577, MAZOTOS 99634033 RESTAURANT ALASIA RESTAURANT LARNACA 38, PIALE PASIA STREET, 6026, LARNACA 24655868 RESTAURANT ALCHEMIES 106-108, ERMOU STREET, STOA KIZI, 6022, LARNACA 24636111, 99518080 RESTAURANT ALEXANDER PIZZERIA ( LARNAKA ) 101, ATHINON AVENUE, 6022, LARNACA 24-655544, 99372013 RESTAURANT ALFA CAFE RESTAURANT ΛΕΩΦ. ΓΙΑΝΝΟΥ ΚΡΑΝΙΔΙΩΤΗ ΑΡ. 20-22, 6049, ΛΑΡΝΑΚΑ 24021200 RESTAURANT ALMAR SEAFOOD BAR RESTAURANT MAKENZY AREA, 6028, LARNACA RESTAURANT, MUSIC AND DANCE AMENTI RESTAURANT 101, ATHINON STREET, 6022, LARNACA 24626712 & 99457311 RESTAURANT AMIKOS RESTAURANT 46, ANASTASI MANOLI STREET, 7520, XYLOFAGOU 24725147 & 99953029 RESTAURANT ANAMNISIS RECEPTION HALL 52, MICHAEL GEORGIOU STREET, 7600, ATHIENOU 24-522533 RESTAURANT ( 1 ) Catering and Entertainment Establishments for LARNAKA 01/02/2019 Category: RESTAURANT Name Address Telephone Category/ies ANNA - MARIA RESTAURANT 30, ANTONAKI MANOLI STREET, 7730, AGIOS THEODOROS 24-322541 RESTAURANT APPETITO 33, ARCH. MAKARIOU C' AVENUE, 6017, LARNACA 24818444 RESTAURANT ART CAFE 1900 RESTAURANT 6, STASINOU STREET, 6023, LARNACA 24-653027 RESTAURANT AVALON 6-8, ZINONOS D. PIERIDI STREET, 6023, LARNACA 99571331 RESTAURANT B. & B. RESTAURANT LARNACA-DEKELIA ROAD, 7041, OROKLINI 99-688690 & 99640680 RESTAURANT B.B. BLOOMS BAR & GRILL 7, ATHINON AVENUE, 6026, LARNACA 24651823 & 99324827 RESTAURANT BALTI HOUSE TANDOORI INDIAN REST. -

4 Bedroom Detached House

4 Bedroom Detached House FOR SALE - € 400,000 EUR https://www.mayfaircyprus.net/p/110060 Prop No. 110060 This four bedroom property is located in the quiet residential area of City: Larnaca Xylpphagou. The premises are very spacious 300 sq.m of covered area and it stands on a good size plot of 3535 sq.m. The property has many extras like Area: Xylofagou two big garages, air-conditioned units all over the house, central heating, Bedrooms: 4 Bedrooms one extra kitchen, 200 olive trees around the area with a huge mature size Bathrooms: 3 Baths garden. This well presented house is ideal as a permanent home. The Real Covered area: 300 m2 Estate is located in Xylofagou close to a wide variety of local amenities and within easy reach of the shops, bars, restaurants and the sandy beach of 2 Plot: 3535 m Ayia Napa. The property comes with title deeds. Accommodation comprises: Title deeds: Yes open plan fitted kitchen, veranda, four bedrooms, guest w.c., en-suite to Property Type: Detached master bedroom, main bathroom, double glazed windows, pressurized water system, air-conditioning units, central heating, garden, store room, utility Condition: Resale room and two covered parking. Property features Air Conditioning En-suite BBQ Area Garden Central Heating Open Plan Fitted Kitchen Covered Parking Pressurized Water System Double Glazing Store Room Mayfair Properties Corner of 1 Arch Makariou III & Gr Afxentiou Ave. Shop 7, Akamia Centre, 6017, Larnaca, Cyprus Tel: +357 248 187 30< Fax: +357 248 187 740 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.mayfaircyprus.com . -

Download the E4 Nature Trail

ils tra ure nat d other Follow the E4 an us. pr Cy EUROPEAN LONG DISTANCE PATH E4 INTRODUCTION The European long distance path E4 was extended to Cyprus following a proposal by the Greek Ramblers Association to the European Ramblers Association, the coordinating body of the European Network of long distance paths. The main partners in Cyprus are the Cyprus Tourism Organisation and the Forestry Department. The path starts at Gibraltar, passes through Spain, France, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, mainland Greece, the Greek island of Crete, to the island of Cyprus. In its Cyprus section, European path E4 connects Larnaka and Pafos international airports. Along the route, it traverses Troodos mountain range, Akamas peninsula and long stretches of cural areas, along regions of enhanced natural beauty and high ecological, historic, archaeological, cultural and scientific value. Few people have the time or the stamina to tackle the whole route in one go. The information given here is a general outline, to assist ramblers identify the path route. It is by no means a detailed description of all aspects of covered areas. Ramblers are strongly advised to research further any path section(s) to be attempted, with particular emphasis in the availability and proximity of overnight licensed accommodation establishments, especially in remote mountain and rural areas. It should be stressed that the route by no means represents all that Cyprus has to offer the rambler. It is primarily designed as cross- country route, and as such is inevitably selective, missing out some fine landscapes and/or cultural sites. It does however provide a sampler of the scenic and cultural variety that is Cyprus. -

Rapid Antigen Testing Units – 24 May 2021 Aiming at the Continuous

Rapid antigen testing units – 24 May 2021 Aiming at the continuous surveillance of the community and the workplaces, the free programmes of rapid antigen testing of the general population and employees are in progress. For the smooth and safe operation of businesses that have been activated according to the Decrees, employers in businesses, as well as the Heads of Departments/Services in the public and wider public sector, are obliged to coordinate the rapid testing of the employees, so that the mandatory weekly rapid antigen testing of at least 50% of the personnel working with physical presence, is ensured. Additionally, the self-employed and the domestic employees and/or people caring for elders or disabled persons or people providing assistance to individuals who are unable to take care of themselves are obligated to participate in the program. It is understood that exempt from the above regulation are the employees who have received the 1st dose of a licenced vaccine and three weeks have elapsed from their vaccination. For example, if a company/organization/department of the public/wider public sector employs 20 people with physical presence, of which 12 have received the 1st dose of the vaccine, the obligation for weekly testing concerns the other 8 individuals (4+4). On Monday, 24 May, the testing units will be operating in the following areas: Operating District Location of testing units hours 8.30 a.m. – Agios Ioannis Gymnasium 6.00 p.m. 7.30 a.m. – “Grigoris Afxentiou” Square, Lemesos 7.30 p.m. Agios Nicolaos Lyceum 1.30 p.m. -

Description - Cost Center Code Post Office Address Working Hours

POST OFFICES Description - Cost Center Code Post Office Address Working Hours LEFKOSIA DISTRICT Cyprus Post Head Offices - 1001 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 07.30-15.00 Lefkosia District Post Office - 2000 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Lefkosia Citizen Center (KE.PO.) 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Latsia Mail Sorting Center - 8000 13, Leoforos Kilkis, 2234 Latsia Agioi Omologitai Post Office - 2030 55, Leoforos Dimostheni Severi, 1080 Lefkosia Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Aglantzia Post Office - 2120 16, Georgiou Griva Digeni, 2108 Aglantzia Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Akropolis Post Office - 2050 4, Grigoriou Karekla, 2023 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Lefkosia Parcels Post Office - 2001 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Egkomi Post Office - 2090 4, Neas Egkomis, 2409 Egkomi Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Dali Post Office - 2140 Leoforos Chalkanoros 56DE, 2540 Dali Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Kakopetria Post Office - 2130 20, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2800 Kakopetria Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Kakopetria Citizen Center (KE.PO.) 20, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2800 Kakopetria Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Kokkinotrimithia Post Office - 2190 59, Grigoriou Afxentiou, 2660 Kokkinotrimithia Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Lakatameia Post Office - 2150 256, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2311 Lakatameia Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Latsia Post Office - 2160 20, Eleftheriou Venizelou, 2235 Latsia Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Lykavittos Post Office - 2080 14, Kallipoleos, 1055 Lefkosia (Lykavittos) Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Pallouriotissa Post Office -

Dams of Cyprus

DAMS OF CYPRUS Α/Α NAME YEAR RIVER TYPE HEIGHT CAPACITY (M) (M3) 1 Kouklia 1900 - Earthfill 6 4.545.000 2 Lythrodonta (Lower) 1945 Koutsos (Gialias) Gravity 11 32.000 3 Kalo Chorio (Klirou) 1947 Akaki (Serrachis) Gravity 9 82.000 4 Akrounta 1947 Germasogeia Gravity 7 23.000 5 Galini 1947 Kampos Gravity 11 23.000 6 Petra 1948 Atsas Gravity 9 32.000 7 Petra 1951 Atsas Gravity 9 23.000 8 Lythrodonta (Upper) 1952 Koutsos (Gialias) Gravity 10 32.000 9 Kafizis 1953 Xeros (Morfou) Gravity 23 113.000 10 Agios Loukas 1955 - Earthfill 3 455.000 11 Gypsou 1955 - Earthfill 3 100.000 12 Kantou 1956 Tabakhana Gravity 15 34.000 (Kouris) 13 Pera Pedi 1956 Gravity 22 55.000 14 Pyrgos 1957 Katouris Gravity 22 285.000 15 Trimiklini 1958 Kouris Gravity 33 340.000 16 Prodromos Reservoir 1962 Off - stream Earthfill 10 122.000 17 Morfou 1962 Serrachis Earthfill 13 1.879.000 18 Lefka 1962 Setrachos Gravity 35 368.000 (Marathasa) 19 Kioneli 1962 Almyros Earthfill 15 1.045.000 (Pediaios) 20 Athalassa 1962 Kalogyros Earthfill 18 791.000 (Pediaios) 21 Sotira - (Recharge) 1962 - Earthfill 8 45.000 22 Panagia/Ammochostou 1962 - Earthfill 7 45.000 23 Ag.Georgios - 1962 - Earthfill 6 90.000 (Recharge) 24 KanliKiogiou 1963 Ghinar (Pediaios) Earthfill 19 1.113.000 25 Ammochostou - 1963 - Earthfill 8 165.000 (Recharge) 26 Paralimni - (Recharge) 1963 - Earthfill 5 115.000 27 Agia Napa - (Recharge) 1963 - Earthfill 8 55.000 28 Ammochostou - 1963 - Earthfill 5 50.000 (Antiflood) 29 Argaka 1964 Makounta Rockfill 41 990.000 30 Mia Milia 1964 Simeas Earthfill 22 355.000 31 Ovgos 1964 Ovgos Earthfill 16 845.000 32 Kiti 1964 Tremithos Earthfill 22 1.614.000 33 Agros 1964 Limnatis Earthfill 26 99.000 34 Liopetri 1964 Potamos Earthfill 18 340.000 35 Agios Nikolaos - 1964 - Earthfill 2 1.365.000 (Recharge) 36 Paralimni Lake - 1964 - Earthfill 1 1.365.000 (Recharge) 37 Ag. -

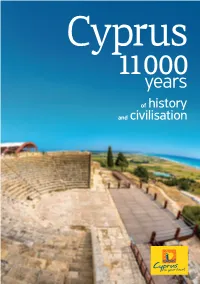

Cyprus 11000 Years of History

Contents Introduction 5 Cyprus 11000 years of history and civilisation 6 The History of Cyprus 7-17 11500 - 10500 BC Prehistoric Age 7 8200 - 1050 BC Prehistoric Age 8 1050 - 480 BC Historic Times: Geometric 9 and Archaic Periods 475 BC - 395 AD Classical, Hellenistic and Roman Periods 10 395 - 1191 AD Byzantine Period 11-12 1192 - 1489 AD Frankish Period 13 1489 - 1571 AD The Venetians in Cyprus 14 1571 - 1878 AD Cyprus becomes part of the Ottoman Empire 15 1878 - 1960 AD British rule 16 1960 - Today The Republic of Cyprus, the Turkish 17 invasion, European Union entry Lefkosia (Nicosia) 18-39 Lemesos (Limassol) 40-57 Larnaka 58-71 Pafos 72-87 Ammochostos (Famagusta) 88-95 Troodos 96-110 Aphrodite Cultural Route Map 111 Wine Route Map 112-113 Cyprus Tourism Offices 114 Cyprus Online www.visitcyprus.com Our official website provides comprehensive information on the major attractions of Cyprus, complete with maps, an updated calendar of events, a detailed hotel guide, downloadable photos and suggested itineraries. You will also find a list of tour operators covering Cyprus, information on conferences and incentives and a wealth of other useful information. Lefkosia Lemesos - Larnaka Limassol Pafos Ammochostos - Troodos 4 Famagusta Introduction Cyprus is a small country with a long history and rich culture. It is not surprising that UNESCO included the Pafos antiquities, Choirokoitia Neolithic settlement and ten of the Byzantine period churches of Troodos on its list of World Heritage Sites. The aim of this publication is to help visitors discover the cultural heritage of Cyprus. The qualified personnel at any of our Information Offices will be happy to assist you in organising your visit in the best possible way. -

Mangiare E Bere a Cipro

MANGIARE E BERE A CIPRO Guida di gastronomia e svago Catering and Entertainment Establishments for LEFKOSIA 05/06/2019 Category: RESTAURANT Name Address Telephone Category/ies 1900 OINOU MELATHRON11-13, PASIKRATOUS STREET, 1011, LEFKOSIA 22667668 & 99622409 RESTAURANT, BAR 48 BISTRO48Α, ARCH. MAKARIOU C AVENUE, 1065, LEFKOSIA 22664848 RESTAURANT A. PARADISE RESTAURANT ( ASTROMERITIS )16, KARYDION STREET, 2722, ASTROMERITIS 22821849, 99527808 RESTAURANT, CAFE ACQUARELLO BEACH RESTAURANT CAFE38, NIKOLA PAPAGEORGIOU STREET, 2940 KATO PYRGOS 96530034, 99620174 RESTAURANT, CAFE ALFA PIZZA ( KLIROU )189, ARCH. MAKARIOU STREET, 2600, KLIROU 22634900 & 99641160 RESTAURANT APERITIVO JETSET LOUNGE1, TZON KENNETY AVENUE, 1075, LEFKOSIA 22100990, 99537317 RESTAURANT ARGENTINA TZIELLARI - CYPRUS RESTAURANT72, PALEAS KAKOPETRIAS STREET, 2800, KAKOPETRIA 99967051, 99886001 RESTAURANT ARTE CUCINARIA RESTAURANT8E, VYZANTIOU STREET, 2064, STROVOLOS 22664799 RESTAURANT ARTISAN'S BURGERBAR20, STASANDROU STREET, 1060, LEFKOSIA 22759300, 99487445 RESTAURANT GEORGE ATELIER3, ARCH. MICHAEL STREET, 1011, LEFKOSIA 22262369 RESTAURANT AVENUE2, EREXTHIOU STREET, 2413, ENGOMI RESTAURANT B R HUB22, ΑΤΗΙΝΟΝ AVENUE, 2040, STROVOLOS 70087018, 99288006 RESTAURANT Παρης BABYLON RESTAURANT6, IASONOS STREET, 1082, LEFKOSIA 22665757, 96221281 RESTAURANT Παύλος BAMBOO CHINESE RESTAURANT185, LEDRAS & ARSINOIS STREET, 1011, LEFKOSIA 22451111 RESTAURANT ( 1 ) Catering and Entertainment Establishments for LEFKOSIA 05/06/2019 Category: RESTAURANT Name Address Telephone Category/ies -

Water Supply Enhancement in Cyprus Through Evaporation Reduction

Water Supply Enhancement in Cyprus through Evaporation Reduction by Chad W. Cox B.S.E. Civil Engineering Princeton University, 1992 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1999 © 1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights Reserved Signature of the Author___ Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 7, 1999 Certified by Dr. E. Eric Adams Senior Research Engineer, Depa94f pf Ti il angEnvironmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by -o4 Professor Andrew J. Whittle Chairman. Denmatint Committee on Graduate Studies Water Supply Enhancement in Cyprus through Evaporation Reduction by Chad W. Cox Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 7, 1999 in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering Abstract The Republic of Cyprus is prone to periodic multi-year droughts. The Water Development Department (WDD) is therefore investigating innovative methods for producing and conserving water. One of the concepts being considered is reduction of evaporation from surface water bodies. A reservoir operation study of the Southern Conveyor Project (SCP) suggests that an average of 6.9 million cubic meters (MCM) of water is lost to evaporation each year. The value of this water is over CYE 1.2 million, and replacement of this volume of water by desalination will cost CYE 2.9 million. The WDD has investigated the use of monomolecular films for use in evaporation suppression, but these films are difficult to use in the field and raise concerns about health effects. -

Economics of Seawater Desalination in Cyprus L

-4 Economics of Seawater Desalination in Cyprus by Mark P. Batho B.S.C.E. (Civil Engineering) Seattle University, Cum Laude, 1996 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE, 1999 0 1999 Mark P. Batho. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part Signature of Author: D6partment of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 7, 1999 Certified by: David H. Marks James Mason Crafts Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor '1~ i Accepted by: 1 "'4-, Andrew J. Whittle Chair, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies L.k7j E I I Economics of Seawater Desalination in Cyprus by Mark P. Batho B.S.C.E. (Civil Engineering) Seattle University, Cum Laude, 1996 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING, MAY 7, 1999 Abstract The Republic of Cyprus is currently suffering from severe drought conditions. This is not uncommon to Cyprus, as they frequently experience three to four year droughts every decade. They are currently in the middle of their fourth year of drought. Some Cypriots believe that the main reason for water shortages is due only to low levels of rainfall (average rainfall in Cyprus is 500 mm per year, and less than 400 mm per year is considered a drought year). -

The Prevention of Torture in Southern Europe

a r u t r o t a l e d n ó e i r c u n assoc t e ia r v t o n t i e o r o f n i p o t n a n l e o v e i a é r t r r u n a p p t e p our la r v o e n t r a p ió de l c a he a s t ci soc for o iation as Report The Prevention of Torture in Southern Europe An Assessment of the Work of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture in the South of Europe Founded in 1977 P.O. Box 2267 CH-1211 Geneva 2 by J.-J. Gautier Tel.(4122) 734 20 88 Fax (4122) 734 56 49 E-mail [email protected] Postal account 12-21656-7 Geneva a r u t r o t a l e d n ó e i r c u n assoc t e ia r v t o n t i e o r o f n i p o t n a n l e o v e i a é r t r r u n a p p t e p our la r v o e n t r a p ió de l c a he a s t ci soc for o iation as Report The Prevention of Torture in Southern Europe An Assessment of the Work of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture in the South of Europe Acts of the seminar held in Oñati, Spain, 17 – 18 April 1997 Geneva, December 1997 I TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS IV EDITOR’S NOTE ABLE OF CONTENTS By Anna Khakee, Programme Officer for Europe, APT 1 T INTRODUCTION 3 1) Opening Speech By Marco Mona, President of the APT 3 2) Opening Speech By Jan Malinowski, Member of the CPT’s Secretariat 5 A) THE CPT AND ITS PARTNERS 11 I) FUNCTIONING OF THE CPT : STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS 13 1) The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment: Operational Practice By Rod Morgan, Dean of the Faculty of Law and Professor of Criminal Justice at the University of Bristol, CPT Expert, Great Britain 13 2) The Liaison Officer - Practice and Potential By Maria José Mota da Matos, Head of Department for the Study and Enforcement of Sentences of the Penitentiary Administration, Ministry of Justice, Portugal 18 3) The Role of the Expert with the CPT By J.J.