UPDATED OKE's PHD THESIS 2012.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legacies of Biafra Conference Schedule - SOAS, University of London, April 21-22

H-AfrLitCine Legacies of Biafra Conference Schedule - SOAS, University of London, April 21-22 Discussion published by Louisa Uchum Egbunike on Monday, April 24, 2017 Legacies of Biafra Conference Schedule - April 21-22, SOAS, University of London Registration is to completed online at www.igboconference.com/tickets For further details about the conference, visit www.igboconference.com Conference Schedule: Thursday 20th April, Khalili Lecture Theatre, SOAS 6:00pm – 8:00pm Preconference Welcome, Film screening: Most Vulnerable Nigerians: The Legacy of the Asaba Massacres by Elizabeth Bird, followed by a Q & A session. Elizabeth Bird will introduce the documentary film and talk about her research and upcoming book about the Asaba Massacres. Film Screening: Onye Ije: The Traveller, An Igbo travelogue on the Umuahia War Museum & The Ojukwu Bunker produced by Brian C. Ezeike and Mazi Waga. The film will be introduced by the producers of the Documentary series, followed by a short Q & A Session. …………………………………………… FRIDAY, 21st APRIL 2017, Brunei Gallery Lecture Theatre & Suite, SOAS 8:30am Conference Registration Opens 9:30am Parallel Panels (A) A1 Panel: Revisiting Biafra A2 Panel: Writing Biafra (please scroll down for speaker details on the A Panels) 11:00am Parallel Panels (B) B1 Roundtable: Global Media and Humanitarian Responses to the Biafra War B2 Roundtable: Real Life Accounts of the War B3 Panel: Child Refugees of the Nigeria-Biafra war (please scroll down for speaker details on the B Panels ) 12:30pm Obi Nwakanma in Conversation with Olu Oguibe Citation: Louisa Uchum Egbunike. Legacies of Biafra Conference Schedule - SOAS, University of London, April 21-22 . -

Mapping Nigeria's Response to Covid-19 the Bold Ones

DIGITAL DIALOGUES A NATIONAL CONVERSATION: MAPPING NIGERIA’S RESPONSE TO COVID-19 POST-EVENT REPORT THE BOLD ONES: NIGERIAN COMPANIES REINVENTING FOR THE NEW NORMAL SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT JULY 2020 AGRIBUSINESS FINANCE MARKETS NIRSAL exists to create a handshake between the Agricultural Value Chain and the Financial Sector in order to boost productivity, food security and the profitability of agribusiness in Nigeria. At the heart of our strategy is the Credit Risk Guarantee (CRG) which enhances the flow of finance and investment into fixed Agricultural Value Chains by serving as a buffer that encourages investors to fund verified bankable projects. Working with financial institutions, farmer groups, mechanization service providers, logistics providers and other actors in the Value Chain, NIRSAL is changing Nigeria's agricultural landscape and delivering food security, financial inclusion, wealth creation and economic growth. THE NIGERIA INCENTIVE-BASED RISK SHARING SYSTEM FOR AGRICULTURAL LENDING De-Risking Agriculture Facilitating Agribusiness Office Address Lagos Office Plot 1581, Tigris Crescent CBN Building www.nirsal.com Maitama District Tinubu Square, Marina You u e Abuja, Nigeria Lagos, Nigeria @nirsalconnect NIRSAL, a Central Bank of Nigeria corporation. DIGITAL DIALOGUES A NATIONAL CONVERSATION: MAPPING NIGERIA’S RESPONSE TO COVID-19 POST-EVENT REPORT THE BOLD ONES: NIGERIAN COMPANIES REINVENTING FOR THE NEW NORMAL SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT Sponsors Moderators and Panelists ZAINAB PROF. AKIN IBUKUN DR. OBIAGELI ALIYU DR. DOYIN OLISA ENGR. -

Senate Committee Report

THE 7TH SENATE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA COMMITTEE ON THE REVIEW OF THE 1999 CONSTITUTION REPORT OF THE SENATE COMMITTEE ON THE REVIEW OF THE 1999 CONSTITUTION ON A BILL FOR AN ACT TO FURTHER ALTER THE PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA 1999 AND FOR OTHER MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH, 2013 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria referred the following Constitution alterations bills to the Committee for further legislative action after the debate on their general principles and second reading passage: 1. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.107), Second Reading – Wednesday 14th March, 2012 2. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.136), Second Reading – Thursday, 14th October, 2012 3. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.139), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 4. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.158), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 5. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.162), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 6. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.168), Second Reading – Thursday 1 | P a g e 4th October, 2012 7. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.226), Second Reading – 20th February, 2013 8. Ministerial (Nominees Bill), 2013 (SB.108), Second Reading – Wednesday, 13th March, 2013 1.1 MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE 1. Sen. Ike Ekweremadu - Chairman 2. Sen. Victor Ndoma-Egba - Member 3. Sen. Bello Hayatu Gwarzo - “ 4. Sen. Uche Chukwumerije - “ 5. Sen. Abdul Ahmed Ningi - “ 6. Sen. Solomon Ganiyu - “ 7. Sen. George Akume - “ 8. Sen. Abu Ibrahim - “ 9. Sen. Ahmed Rufa’i Sani - “ 10. Sen. Ayoola H. Agboola - “ 11. Sen. Umaru Dahiru - “ 12. Sen. James E. -

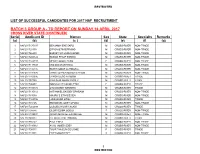

Batch 3 Group A

RESTRICTED LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR 2017 NAF RECRUITMENT BATCH 3 GROUP A - TO REPORT ON SUNDAY 16 APRIL 2017 CROSS RIVER STATE (CONTINUED) Serial Applicant ID Names Sex State Specialty Remarks (a) (b) (c ) (d) (e) (f) (g) 1 NAF2017175197 BENJAMIN ENE EKPO M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 2 NAF201728378 EFFIOM ETIM EFFIONG M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 3 NAF201746430 BASSEY SYLVANUS OKON M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 4 NAF2017200122 EDIKAN PHILIP ESSIEN M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 5 NAF2017148737 MERCY OKON EKPO F CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 6 NAF2017117347 ENE EDEM ANTIGHA M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 7 NAF2017186435 EDWIN IOBAR ACHIBONG M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 8 NAF2017191076 CHRISTOPHER MOSES EFFIOM M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 9 NAF2017166695 UKPONG ESO AKABOM M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 10 NAF201767788 PAULINUS OKON BASSEY M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 11 NAF201796402 IMMACULATA OKON ETIM F CROSS-RIVER TRADE 12 NAF2017100172 OTU BASSEY KENNETH M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 13 NAF2017135112 NATHANIEL BASSEY EPHRAIM M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 14 NAF201733038 MAURICE ETIM ESSIEN M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 15 NAF2017169796 LUKE OGAR OTAH M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 16 NAF201745165 EMMANUEL ODEY OFUNA M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 17 NAF2017202699 OGBUDU HILARY AGABI M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 18 NAF201798686 GLORY ELIMA ODIDO F CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 19 NAF2017199991 ADADA MICHAEL EKANNAZE M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 20 NAF201749812 CLEMENT ADIE BISONG M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 21 NAF201786142 PAUL ENEJI . M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 22 NAF2017180661 ACHU JAMES ODEY M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 23 NAF201706031 TOURITHA EUNICE USHIE F CROSS-RIVER -

Approval Page

1 LABOUR UNREST AND UNDERDEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA: AN APPRAISAL OF 2000-2013 BY MUOH GEORGE MADU PS/2009/294 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE CARITAS UNIVERSITY AMORJI-NIKE EMENE ENUGU AUGUST 2013. 2 Approval Page This is to certify that this thesis by Muoh George Madu under the supervision of the under signed has been carefully supervised, read and approved for its contribution to knowledge and literacy and therefore met the requirement for the award of Bachelor of Science (B.Sc) Degree in Political Science __________________ _____________ Dr. Omemma, D.A Date Project Supervisor __________________ _____________ Dr. Omemma, D.A. Date Head of Department ___________________ _____________ External Examiner Date 3 Dedication I dedicate this research work to God Almighty. Also to my beloved parent Chief and Mrs. F.O.C. Muoh and my siblings Nonso, Ebere, Ifeoma, Obiora, Amaka Ugochukwu, Uchenna and Chinedu. 4 Acknowledgment The journey towards the attainment of this academic height has been a journey of the maggai torturous windy and rough. Infact, without supernatural inspiration and human facilitations, the journey to the pinnacle of my academic attainment would have been a pipe dreams. Thus I owe a lot of debts of gratitude to both visible and invisible forces. First and foremost, is God Almighty whose compassion and boundless blessings made it possible for me to weather the storm of attaining this enviable academic height. No amount of gift or sacrifice would be commensurate to God’s wondrous deeds in my life and that is why in reciprocation, I pledge never to cease praising and testifying God’s overflowing love and kindness. -

Nigeria's Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative

Nigeria’s Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative Just a Glorious Audit? Nicholas Shaxson November 2009 Nigeria’s Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative Just a Glorious Audit? Nicholas Shaxson November 2009 © Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2009 Chatham House (the Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinion of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London, SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: +44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org.uk Charity Registration No. 208223 ISBN 978 1 86203 219 4 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Designed and typeset by Soapbox Communications Limited www.soapboxcommunications.co.uk Contents Preface v About the Author vii Executive Summary viii List of Abbreviations x 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Global EITI 1 1.2 Nigeria’s oil industry 3 1.3 NEITI: brief history and context 4 1.3.1 Technical and procedural context 4 1.3.2 Political history and context 6 1.4 EITI’s and NEITI’s goals 7 1.5 Rulers, oil companies, citizens – and NEITI 8 2. Reforms, -

The Doctrine of Fedralism and the Clamour for Restructuring of Nigeria for Good Governance: Issues and Challenges

International Journal of Advanced Academic Research | Social & Management Sciences | ISSN: 2488-9849 Vol. 4, Issue 4 (April 2018) THE DOCTRINE OF FEDRALISM AND THE CLAMOUR FOR RESTRUCTURING OF NIGERIA FOR GOOD GOVERNANCE: ISSUES AND CHALLENGES Ebiziem, Jude Ebiziem Department of Political Science, Alvan Ikoku Federal College of Education, Owerri Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected] +2348035077757 Onyemere, Fineboy Ezenwoko National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN) [email protected] +2348025172269 ABSTRACT The paper “the doctrine of federalism and the clamour for restructuring of Nigeria for good governance” draws our attention to the recent agitations by various groups on the path of true federalism and good governance in Nigeria. The broad objectives of this paper is to examine the Nigeria structure of federalism in recent time and identify the factors affecting incessant agitations, and determine the process of restructuring Nigeria for good governance. The paper reviewed relevant related literature and adopted K.C Wheare’s theory of federalism, as its theoretical framework, while its methods of research were basically descriptive and historical designs. The qualitative data were mostly generated largely from the documentary sources. The paper revealed among others, that the calls for restructuring is borne out of some perceived levels of injustice, inequality and discontentment, witnessed by Nigeria society as a result of bad leadership and faulty federalism which has brought myriads of socio-political and economic problems and has resulted to incessant fallouts between various regions, ethnic groups and federal government. The paper recommends inter alia; that although, Nigeria is a federation, there is need for central government and the federating units to understand their differences, build consensus and adopt measures that would accommodate all and enhance good governance. -

FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Wednesday, 15Th May, 2013 1

7TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECOND SESSION NO. 174 311 THE SENATE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Wednesday, 15th May, 2013 1. Prayers 2. Approvalof the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Announcements (if any) 5. Petitions PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. National Agricultural Development Fund (Est. etc) Bill 2013(SB.299)- First Reading Sen. Abdullahi Adamu (Nasarauia North) 2. Economic and Financial Crime Commission Cap E 1 LFN 2011 (Amendment) Bill 2013 (SB. 300) - First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade (Be1l11eNorth East) 3. National Institute for Sports Act Cap N52 LFN 2011(Amendment) Bill 2013(SB.301)- First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade (Benue North East) 4. National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) Act Cap N30 LFN 2011 (Amendment) Bill 2013 (SB.302)- First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade tBenue North East) 5. Federal Highways Act Cap F 13 LFN 2011(Amendment) Bill 2013(SB. 303)- First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade (Benue North East) 6. Energy Commission Act Cap E 10 LFN 2011(Amendment) Bill 2013 (SB.304)- First Reading Sen. Ben Ayade (Cross Riner North) 7. Integrated Farm Settlement and Agro-Input Centres (Est. etc) Bill 2013 (SB.305)- First Reading Sen. Ben Ayade (Cross River North) PRESENTATION OF A REPORT 1. Report of the Committee on Ethics, Privileges and Public Petitions: Petition from Inspector Emmanuel Eldiare: Sen. Ayo Akinyelure tOndo Central) "That the Senate do receive the Report of the Committee on Ethics, Privileges and Public Petitions in respect of a Petition from INSPECTOR EMMANUEL ELDIARE, on His Wrongful Dismissal by the Nigeria Police Force" - (To be laid). PRINTED BY NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PRESS, ABUJA 312 Wednesday, 15th May, 2013 174 ORDERS OF THE DAY MOTION 1. -

The Jonathan Presidency, by Abati, the Guardian, Dec. 17

The Jonathan Presidency By Reuben Abati Published by The Jonathan Presidency The Jonathan Presidency By Reuben Abati A review of the Goodluck Jonathan Presidency in Nigeria should provide significant insight into both his story and the larger Nigerian narrative. We consider this to be a necessary exercise as the country prepares for the next general elections and the Jonathan Presidency faces the certain fate of becoming lame-duck earlier than anticipated. The general impression about President Jonathan among Nigerians is that he is as his name suggests, a product of sheer luck. They say this because here is a President whose story as a politician began in 1998, and who within the space of ten years appears to have made the fastest stride from zero to “stardom” in Nigerian political history. Jonathan himself has had cause to declare that he is from a relatively unknown village called Otuoke in Bayelsa state; he claims he did not have shoes to wear to school, one of those children who ate rice only at Xmas. When his father died in February 2008, it was probably the first time that Otuoke would play host to the kind of quality crowd that showed up in the community. The beauty of the Jonathan story is to be found in its inspirational value, namely that the Nigerian dream could still take on the shape of phenomenal and transformational social mobility in spite of all the inequities in the land. With Jonathan’s emergence as the occupier of the highest office in the land, many Nigerians who had ordinarily given up on the country and the future felt imbued with renewed energy and hope. -

Chapter One: Introduction

ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF PSYCHOSOCIAL AND ACADEMIC PROBLEMS OF WORKING SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS IN LAGOS STATE, NIGERIA BY NWOKEDINOBI, JOY NGOZI MATRICULATION NO: 919003104 B.A (FRENCH), UNIVERSITY OF BENIN 1984 PGDE, UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS 1988 M.ED (GUIDANCE AND COUNSELLING), UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS 1992 A THESIS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATIONS (WITH PSYCHOLOGY) SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POST GRADUATE STUDIES. UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PH.D) IN GUIDANCE AND COUNSELLING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS NOVEMBER 2010 1 APPROVAL This research has been approved for the department of educational foundations and the school of post graduate studies, University of Lagos BY: DR. C.E OKOLI (Supervisor) DR. (Mrs) I. I. ABE (Supervisor) Prof. (Mrs) A. M. Olusakin DATE Head of Department 2 SCHOOL OF POST-GRADUATE STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS CERTIFICATION This is to certify that the Thesis: “ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF PSYCHOSOCIAL AND ACADEMIC PROBLEMS OF WORKING SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS IN LAGOS STATE, NIGERIA.” Submitted to the School of Post-graduate Studies University of Lagos For the award of degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) is a record of original research carried out BY NWOKEDINOBI, JOY NGOZI In the Department of Educational Foundations ----------------------------------- ------------------ ------------- AUTHOR’S NAME SIGNATURE DATE ----------------------------------- ------------------ ------------ 1st SUPERVISOR’S NAME SIGNATURE DATE -

Tuesday, 17Th April, 2018

8TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY 422 THIRD SESSION NO. 146 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 17th April, 2018 1. Prayers 2. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Announcements (if any) 5. Petitions PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Maritime Security Operations Coordinating Board Act (Amendment) Bill, 2018 (HB. 1056) – First Reading Sen. Ahmad Lawan (Yobe North-Senate Leader). 2. Fisheries Institute of Nigeria (Est, etc) Bill, 2018 (HB. 595) – First Reading Sen. Ahmad Lawan (Yobe North-Senate Leader). 3. Federal University of Education Aguleri, Anambra State (Est, etc) Bill, 2018 (SB. 653) – First Reading Sen. Stella Oduah (Anambra North) and Sen. Victor C. Umeh (Anambra Central). 4. Independent National Electoral Commission Act 2010 (Amendment) Bill, 2018 (SB. 654) – First Reading Sen. Suleiman M. Nazif (Bauchi North). 5. Nigerian Security and Civil Defence Corps Act 2003 (Amendment) Bill, 2018 (SB. 655) – First Reading Sen. Ahmed Ogembe (Kogi Central). 6. National Assembly Budget and Research Office (Est, etc) Bill, 2018 (SB. 656) – First Reading Sen. Ahmad Lawan (Yobe North-Senate Leader). 7. Corporate Manslaughter Bill, 2018 (SB. 657) – First Reading Sen. Ahmad Lawan (Yobe North-Senate Leader). 8. Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria (Est, etc) Bill, 2018 (SB. 658) – First Reading Sen. Ahmad Lawan (Yobe North-Senate Leader). 9. National Post Graduate College of Medical Laboratory Science (Est, etc) Bill, 2018 (SB. 659) – First Reading Sen. Ahmad Lawan (Yobe North-Senate Leader). 10. Federal Capital Territory Civil Service Commission (Est, etc) Bill, 2018 (SB. 660) – First Reading Sen. Ahmad Lawan (Yobe North-Senate Leader). 11. Chartered Institute of Human Capital Development of Nigeria (Est, etc) Bill, 2018 (SB. -

Governing “Ethnicized” Public Sphere: Lessons from the Nigerian Case

CODESRIA 12th General Assembly Governing the African Public Sphere 12e Assemblée générale Administrer l’espace public africain 12a Assembleia Geral Governar o Espaço Público Africano ةيعمجلا ةيمومعلا ةيناثلا رشع ﺣﻜﻢ اﻟﻔﻀﺎء اﻟﻌﺎم اﻹﻓﺮﻳﻘﻰ Governing “Ethnicized” Public Sphere: Lessons from the Nigerian Case Orji Nkwachukwu Ebonyi State University 07-11/12/2008 Yaoundé, Cameroun Abstract This paper analyzes the role of power-sharing in governing the Nigerian public sphere. It examines the meaning, actors, procedures and practices of power-sharing in Nigeria. The paper assesses the opportunities and challenges arising from the use of power-sharing as a method of governing the public sphere and highlights the lessons that Nigeria’s experience presents to other African countries struggling with the challenge of ethnic diversity. The paper argues that power-sharing as it is being practiced in Nigeria widens the asymmetrical and oligarchic power of the dominant elite groups, creates a dependency syndrome, and hampers the growth of democracy. It contends that the Nigerian case exposes the contradictions and limitations of power-sharing as an institutional approach to the regulation of the public sphere. Introduction Nigeria’s heritage of ethnic diversity has had an overwhelming impact on the country’s public sphere, leading to its “ethnicization”. On the other hand, the stiff political competition among the elite has resulted in the “politicization” of ethnicity in the country. The result of the above is a highly contested public sphere, which has been made the arena of rhetorical confrontations between various ethnic groups in the country. However since the 1970s, the Nigerian political elite have adopted power-sharing as a strategy to manage inter-group relations, mitigate the negative effects of ethnic politics, and transform the “ethnicized” public sphere through the introduction of the discourse of “unity in diversity”.