Imagery and Imaginary of Islander Identity: Older People and Migration in Irish Small-Island Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies in Irish Craniology (Aran Islands, Co. Galway)

Z- STUDIES IN IRISH ORANIOLOGY. (ARAN ISLANDS, CO. GALWAY.) BY PROFESSOR A. C. HADDON. A PAPER Read before the ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY, December 12, 1892; and “ Reprinted from the Procrrimnos,” 3rd Ser., Vol, II.. No. 5. \_Fifty copies only reprinted hy the Academy for the Author.] DUBLIN: PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, BY PONSONBY AND WELDRICK, PKINTBRS TO THB ACAHRMY. 1893 . r 759 ] XXXVIII. STUDIES IN lEISH CKANIOLOGY: THE ARAN ISLANDS, CO. GALWAY.* By PROFESSOR A. C. HADDON. [Eead December 12, 1892.] The following is the first of a series of communications which I pro- pose to make to the Academy on Irish Craniology. It is a remarkable fact that there is scarcely an obscure people on the face of the globe about whom we have less anthropographical information than we have of the Irish. Three skulls from Ireland are described by Davis and Thumam in the “Crania Britannica” (1856-65); six by J. Aitken Meigs in his ‘ ‘ Catalogue of Human Crania in the Collection of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia ” two by J. Van der Hoeven (1857) ; in his “ Catalogus craniorum diversarum gentium” (1860); thirty- eight (more or less fragmentary), and five casts by J. Barnard Davis in the “Thesaurus craniorum” (1867), besides a few others which I shall refer to on a future occasion. Quite recently Dr. W. Frazer has measured a number of Irish skulls. “ A Contribution to Irish Anthropology,” Jour. Roy. Soc. Antiquarians of Ireland, I. (5), 1891, p. 391. In addition to three skuUs from Derry, Dundalk, and Mary’s Abbey, Dublin, Dr. -

PSAI 2014 Programme Final

PSAI Conference 2014: overview Friday 17 October 2014 Type of Session Session title Time Venue PSAI Executive Committee Meeting 12:30- Inishmore 14:00 Arrival and From Foyer (beside Registration 13:00 Inishturk) Parallel Session 1 A. Irish Politics 1 14:00- Inishmore B. Northern Ireland: international 15:30 Inishturk dimensions C. Participatory and Deliberative Inisheer Democracy: theory and praxis Tea/Coffee Break 15:30- 16:00 Parallel Session 2 A. Global Political Society 16:00- Inishmaan B. Dominating Unionism 17:30 Inishturk C. Political Theory Inisheer D. Publishing workshop with Tony Mason, Inishmore Manchester University Press Event 30th anniversary of the PSAI: 18:00- Inisturk Celebration/Book Launch and Roundtable 19:00 Saturday 18 October, 2014 Type of Session Title of Session Time Venue Parallel Session 3 A. Foreign Policy, Middle East and 9:00- Inisheer International Relations 10:30 B. Re-examining the Roman Catholic Inishturk Church’s Role in 20th C. Irish Politics C. Republicanism, Power and the Inishmaan Constitution D. Remembering conflict and educating Inishmore for peace Tea/Coffee break 10:30-11 Parallel Session 4 A. Gendering Politics and Political 11:00- Inisheer Discourse in the National and 12:30 International Arena B. Conflict and Divided Societies 1 Inishmaan C. Northern Ireland after the Peace Inishturk D. Teaching and Learning Inishmore Lunch 12:30- Harvest Cafe 13:30 (up the stairs) PSAI Specialist 12:30- Group Meetings 13:30 1 Plenary Session Peter Mair Memorial Lecture by 13:30- Inishturk Professor Donatella della Porta (European 14:30 University Institute): Political cleavages in times of austerity. -

West of Ireland Paintings at the National Gallery of Ireland from 1800 to 2000

West of Ireland Paintings at the National Gallery of Ireland from 1800 to 2000 I The West of Ireland National Gallery of Ireland / Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann West of Ireland Paintings at the National Gallery of Ireland from 1800 to 2000 Marie Bourke With contributions by Donal Maguire And Sarah Edmondson II Contents 5 Foreword, Sean Rainbird, Director, National Gallery of Ireland 23 The West as a Significant Place for Irish Artists Contributions by Donal Maguire (DM), Administrator, Centre for the Study of Irish Art 6 Depicting the West of Ireland in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Dr Marie Bourke, Keeper, Head of Education 24 James Arthur O’Connor (1792–1841), The Mill, Ballinrobe, c.1818 25 George Petrie (1790–1866), Pilgrims at Saint Brigid’s Well, Liscannor, Co. Clare, c.1829–30 6 Introduction: The Lure of the West 26 Frederic William Burton (1816–1900), In Joyce Country (Connemara, Co. Galway), c.1840 6 George Petrie (1790–1866), Dún Aonghasa, Inishmore, Aran Islands, c.1827 27 Frederic William Burton (1816–1900), The Aran Fisherman’s Drowned Child, 1841 8 Timeline: Key Dates in Irish History and Culture, 1800–1999 28 Augustus Burke (c.1838–1891), A Connemara Girl 10 Curiosity about Ireland: Guide books, Travel Memoirs 29 Bartholomew Colles Watkins (1833–1891), A View of the Killaries, from Leenane 10 James Arthur O’Connor (1792–1841), A View of Lough Mask 30 Aloysius O’Kelly (1853–1936), Mass in a Connemara Cabin, c.1883 11 Frederic William Burton (1816–1900), Paddy Conneely (d.1850), a Galway Piper 31 Walter Frederick Osborne (1859–1903), A Galway Cottage, c.1893 32 Jack B. -

Terrain of the Aran Islands Karen O'brien

Spring 2006 169 ‘Ireland mustn’t be such a bad place so’: Mapping the “Real” Terrain of the Aran Islands Karen O’Brien Martin McDonagh’s The Cripple of Inishmaan (1996) responds to and encodes the complexities of representational and ecological issues surrounding life on the rural landscape of the Aran Islands. The three islands that constitute the Aran Islands—Inisheer, Inishmaan, and Inishmore—occupy a unique and dual position of marginality and liminality; they not only reside off the border of the western coast of Ireland but also inhabit an indeterminate space between America and Europe. The archipelagos are described by Irish poet Seamus Heaney as a place “Where the land ends with a sheer drop / You can see three stepping stones out of Europe.”1 Inishmaan employs three strategic interrogations—representation, structure, and aesthetics—that coincide with the project of collaborative ecology. The first strategy juxtaposes two contrasting representations of Ireland’s 1930s rural west, problematizing the notion of a definable Irishness in relation to the unique Arans landscape. Inishmaan revolves around the filming of the American documentary Man of Aran (1934), which claims authenticity in its representation of actual island residents. McDonagh’s depiction of the Aran community, however, contradicts the documentary’s poetic vision of the Aran Islands as a pristine landscape. In scene eight, for example, the screening of Man of Aran does not reflect a mirror image of the Aran residents represented in the play; the film, contrarily, incites mockery. Despite its claim of historical authenticity and authority, the documentary proves fictional. Inishmaan contests the legitimacy of Man of Aran explicitly as well as a history of romanticized notions of western Irish identity implicitly. -

Copyrighted Material

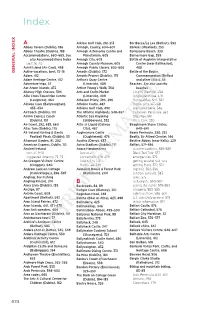

Index A Arklow Golf Club, 212–213 Bar Bacca/La Lea (Belfast), 592 Abbey Tavern (Dublin), 186 Armagh, County, 604–607 Barkers (Wexford), 253 Abbey Theatre (Dublin), 188 Armagh Astronomy Centre and Barleycove Beach, 330 Accommodations, 660–665. See Planetarium, 605 Barnesmore Gap, 559 also Accommodations Index Armagh City, 605 Battle of Aughrim Interpretative best, 16–20 Armagh County Museum, 605 Centre (near Ballinasloe), Achill Island (An Caol), 498 Armagh Public Library, 605–606 488 GENERAL INDEX Active vacations, best, 15–16 Arnotts (Dublin), 172 Battle of the Boyne Adare, 412 Arnotts Project (Dublin), 175 Commemoration (Belfast Adare Heritage Centre, 412 Arthur's Quay Centre and other cities), 54 Adventure trips, 57 (Limerick), 409 Beaches. See also specifi c Aer Arann Islands, 472 Arthur Young's Walk, 364 beaches Ahenny High Crosses, 394 Arts and Crafts Market County Wexford, 254 Aille Cross Equestrian Centre (Limerick), 409 Dingle Peninsula, 379 (Loughrea), 464 Athassel Priory, 394, 396 Donegal Bay, 542, 552 Aillwee Cave (Ballyvaughan), Athlone Castle, 487 Dublin area, 167–168 433–434 Athlone Golf Club, 490 Glencolumbkille, 546 AirCoach (Dublin), 101 The Atlantic Highlands, 548–557 Inishowen Peninsula, 560 Airlink Express Coach Atlantic Sea Kayaking Sligo Bay, 519 (Dublin), 101 (Skibbereen), 332 West Cork, 330 Air travel, 292, 655, 660 Attic @ Liquid (Galway Beaghmore Stone Circles, Alias Tom (Dublin), 175 City), 467 640–641 All-Ireland Hurling & Gaelic Aughnanure Castle Beara Peninsula, 330, 332 Football Finals (Dublin), 55 (Oughterard), -

Galway Book(AW):Master Wicklow - English 5/1/11 11:21 Page 1

JC291 NIAH_Galway Book(AW):master wicklow - english 5/1/11 11:21 Page 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY GALWAY JC291 NIAH_Galway Book(AW):master wicklow - english 5/1/11 11:21 Page 2 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY GALWAY Foreword MAP OF COUNTY GALWAY From Samuel Lewis’ Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, published London, 1837. Reproduced from a map in Trinity College Dublin with the permission of the Board of Trinity College The Architectural Inventory of County is to explore the social and historical context Galway took place in three stages: West Galway of the buildings and structures and to facilitate (Connemara and Galway city) in 2008, South a greater appreciation of the architectural Galway (from Ballinasloe southwards) in 2009 heritage of County Galway. and North Galway (north of Ballinasloe) in 2010. A total of 2,100 structures were recorded. Of these some 1,900 are deemed worthy of The NIAH survey of County Galway protection. can be accessed on the Internet at: The Inventory should not be regarded as www.buildingsofireland.ie THE TWELVE PINS, exhaustive and, over time, other buildings and CONNEMARA, WITH structures of merit may come to light. The BLANKET BOG IN NATIONAL INVENTORY FOREGROUND purpose of the survey and of this introduction of ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE 3 JC291 NIAH_Galway Book(AW):master wicklow - english 5/1/11 11:21 Page 4 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY GALWAY Introduction SLIEVE AUGHTY THE CLADDAGH, MOUNTAINS GALWAY, c.1900 The Claddagh village, at the mouth of the River Corrib, had its own fishing fleet and a 'king'. -

Census 2011 – Results for County Galway

Census 2011 – Results for County Galway Population Results Social Inclusion Unit Galway County Council Table of Contents Page Summary 3 Table 1 Population & Change in Population 2006 - 2011 4 Table 2 Population & Change in Population 2006 – 2011 by Electoral Area 4 Figure 1 Population Growth for County Galway 1991 - 2011 5 Table 3 Components of Population Change in Galway City, Galway 5 County, Galway City & County and the State, 2006 - 2011 Table 4 Percentage of Population in Aggregate Rural & Aggregate Town 6 Areas in 2006 & 2011 Figure 2 Percentage of Population in Aggregate Rural & Aggregate Town 6 Areas in County Galway 2006 & 2011 Table 5 Percentage of Males & Females 2006 & 2011 6 Table 6 Population of Towns* in County Galway, 2002, 2006 & 2011 & 7 Population Change Table 7 Largest Towns in County Galway 2011 10 Table 8 Fastest Growing Towns in County Galway 2006 - 2011 10 Table 9 Towns Most in Decline 2006 – 2011 11 Table 10 Population of Inhabited Islands off County Galway 11 Map 1 Population of EDs in County Galway 2011 12 Map 2 % Population Change of EDs in County Galway 2006 - 2011 12 Table 11 Fastest Growing EDs in County Galway 2006 – 2011 13 Table 12 EDs most in Decline in County Galway 2006 - 2011 14 Appendix 1 Population of EDs in County Galway 2006 & 2011 & Population 15 Change Appendix 2 % Population Change of all Local Authority Areas 21 Appendix 3 Average Annual Estimated Net Migration (Rate per 1,000 Pop.) 22 for each Local Authority Area 2011 2 Summary Population of County Galway • The population of County Galway (excluding the City) in 2011 was 175,124 • There was a 10% increase in the population of County Galway between 2006 and 2011. -

Production Area: DL-LF Location: Lough Foyle

Molluscan Shellfish Production Areas, Sample Points and Co-ordinates for Biotoxin and Phytoplankton Samples. December 2016 Species names / Common names Scientific Name Common Name Crassostrea gigas Pacific Oyster Ensis arcuatus Arched Razor Shell Ensis ensis Pod Razor Shell Ensis siliqua Sword Razor Shell Mytilus edulis Blue Mussel Pecten maximus King Scallop Ostrea edulis Flat/Native Oyster Tapes philipinarum Manilla Clam Tapes semidecussata Paracentrotus lividus Sea Urchin Aequipecten opercularis Queen Scallop Cerastoderma edule Cockle Spisula solida Thick Trough Shell / Surf Clam Dosinia exoleta Rayed Artemis Glycymeris glycymeris Dog Cockle Haliotis discus hannai Japanese Green Abalone Venerupis senegalensis Carpet Shell Venus verrucosa Warty Venus Patella vulgata Common Limpet Littorina littorea Periwinkle Buccinum undatum Common Whelk Echinus esculentus Edible Sea Urchin Production Area Maps Table of Contents Lough Foyle ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Tra Breaga .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Lough Swilly ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Mulroy Bay ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Sheephaven -

Natura Impact Report

NATURA IMPACT REPORT IN SUPPORT OF THE APPROPRIATE ASSESSMENT OF THE VARIATION NO. 2(B) TO THE GALWAY COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2015-2021 IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS OF ARTICLE 6(3) OF THE EU HABITATS DIRECTIVE for: Galway County Council Aras an Chontae Prospect Hill, Co. Galway by: CAAS Ltd. 1st Floor, 24-26 Ormond Quay, Dublin 7 JUNE 2018 Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Licence Number 2015/20CCMA/Galway County Council. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright. © Ordnance Survey Ireland Appropriate Assessment of the Variation No. 2(b) to the Galway County Development Plan 2015 - 2021 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Legislative Context ............................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Guidance ............................................................................................................................. 2 1.4 Approach ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.5 Relationship between the Appropriate Assessment process and the Plan ................................. 4 2 Description and background of the Variation No. 2(b) to -

(1899±1901) Cre- Was Small, with a Shallow Stage Which Dictated Ated by W.B

A Abbey Theatre The opening of the Abbey from a conversion of the Mechanics' Hall in Theatre on 27 December 1904 followed from Lower Abbey Street and a disused morgue, the Irish Literary Theatre (1899±1901) cre- was small, with a shallow stage which dictated ated by W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, with simple sets. But though poorly equipped, the Edward Martyn and George Moore, to pro- early Abbey was aesthetically innovative. duce a `school of Celtic and Irish dramatic Robert Gregory and Charles Ricketts literature'. When Yeats joined forces with the designed for it, Gordon Craig's screens were self-trained Fay brothers ± William the stage first used on its stage, and Ninette de Valois manager and comedian, and Frank the verse- set up a ballet school for theatre use. In 1905 a speaker ± their company (augmented import- permanent salaried company was established antly by Synge and the talented Allgood and controlling powers were given to the sisters) had the potential to create an entirely directors (some actors seceded, thinking the new kind of Irish theatre, one which aimed, changes contrary to nationalist principles). as a later Abbey playwright, Thomas Kilroy, The Abbey's claim to be a national theatre put it, to `weld the fracture between the was aggressively tested by Catholics and Anglo-Irish and Gaelic Ireland'. The Irish nationalists in their audiences. The peasant National Theatre Society became in 1904 drama was the field where cultural interests the National Theatre Society (NTS) Ltd, clashed most spectacularly. Lady Gregory familiarly known from its inception as the popularized the genre with one-act comedies Abbey Theatre. -

Outrage Reports, Co. Clare for the Years 1826 and 1829-1831

Chief Secretary’s Office Registered Papers – Outrage Reports, Co. Clare for the years 1826 and 1829-1831. Michael Mac Mahon CSO= Chief Secretary’s Office; RP= Registered papers; OR= Outrage Reports. CSO/RP/OR/1826/16. Letter from Rev Frederick Blood, Roxton, Corofin, [County Clare], [possibly to Henry Goulburn, Chief Secretary], suggesting that government offer a reward for information on the recent burning of Mr Synge’s school house which operates under the inspection of the Kildare [Place Society]. Refuting the claim that Synge forced parents to send their children to the school. Claiming that if parents were left to themselves they would support the schools. Also draft reply [probably from Goulburn], suggesting that a reward is not necessary in this case. 2 items; 6pp. 28 Aug 1826. CSO/RP/OR/1826/113. Letter from D Hunt, Kilrush, [County Clare], to William Gregory, Under Secretary, forwarding information sworn by James Murphy, pensions of the 57th Regiment of Foot, against Michael Kelleher, a vagrant, concerning the alleged retaking of a still from the excise by Patrick Cox and Patrick Regan near Carrick on Shannon. Requesting further information on the alleged crime. Also statements sworn by Kelleher, formerly of [?], County Roscommon and Murphy of [?Carriacally], County Clare. Includes annotation from Henry Joy, Solicitor General, stating that the men must be released. 3 items; 8pp. 29 Jul 1826. CSO/RP/OR/1826/159. Letter from Michael Martin, magistrate of County Clare, Killaloe, [County Clare], to William Gregory, Under Secretary, reporting on the discovery of a gang of coiners and requesting that William Wright who provided information be compensated. -

The LAG Composition; the LAG Area; Total Available Funding; the Key

The LAG composition; FORUM currently has a Board of Directors of 19 (up to 24 members set out in the guidelines) and is comprised of voluntary and community and statutory sectors, Local Authority representatives and the four Pillars. The voluntary and community sector representatives include community networks, groups representative of older people, young people, persons with disabilities and women. Other members include four County Councillors and the County Manager’s nominee. The four Pillars - IFA, IBEC, Trade Unions and Environmental nominated their representatives and the statutory organisations include the GRETB and Teagasc. The LAG area; The FORUM LDS covers an extensive catchment area that extends from Lough Corrib on the outskirts of Galway City to Clifden on the edge of the Atlantic coast and from Killary Harbour which borders with County Mayo to Lettermullen on the South at the entrance to Galway Bay. It also has four inhabited off-shore islands Inishmore, Inishmaan, Inisheer and Inishbofin, a 35km border with County Mayo and a coastline which stretches from Leenane to na Forbacha, just west of Galway City. Another important feature is that the region contains the largest Gaeltacht area in the State (see Figure 5, and Appendix XII for a full list of Electoral Divisions). The territory is an innate functional area and corresponds naturally with the administrative area of the Municipal District of Connemara (here after referred to as Connemara). It has a surface area of 2050Sq/Km and a population of 39,238 (CSO, 2011). Clifden with a population of 2,613 is the main town in the area.