The Flora of the Aran Islands1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silver Strand Silverstrand Has a Safe, Shallow, Sandy Beach of Approximately 0.25Km Bounded on One Side by a Cliff and the Other by Rocks

Silver Strand Silverstrand has a safe, shallow, sandy beach of approximately 0.25km bounded on one side by a cliff and the other by rocks. It is particularly popular with and suitable for young families. It faces directly into Galway Bay giving spectacular views. There is a promenade with parking capacity for about 60 vehicles. It is suitable for swimming at low tide but the beach is largely covered during high tides. It is lifeguarded during the summer months. Blue Flag standard (2005). Barna Golf and Country Club Corbally, Barna, Co. Galway Telephone: +353 91 592677 Fax: +353 91 592674 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.bearnagolfclub.com Located approx. 8km from Galway, and 3km north of Bearna village, this golf course is set in typical rugged Connemara countryside with fairways constructed between rocks and heather. The course was designed to suit all abilities. Bearna golf course is already being hailed as one of Ireland's finest. The inspired creativity of its designer R.J. Browne in the siting of tees and sand-based greens in the celebrated beauty of West of Ireland's Connemara landscape has produced a course of glamorously porportioned holes. Water comes into play at thirteen of the eighteen holes, each one boasting unique features which together test the golfer's total repertoire of skills. The final holes especially provide a spectacular finish to a satisfying and memorable experience. Caddy hire available. Dress code is neat & casual. Full canteen facilities available with full bar menu and restaurant. Course designed by Robert J Browne. Course length (m): 6174 Athenry Golf Club Palmerstown, Oranmore, Co. -

Studies in Irish Craniology (Aran Islands, Co. Galway)

Z- STUDIES IN IRISH ORANIOLOGY. (ARAN ISLANDS, CO. GALWAY.) BY PROFESSOR A. C. HADDON. A PAPER Read before the ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY, December 12, 1892; and “ Reprinted from the Procrrimnos,” 3rd Ser., Vol, II.. No. 5. \_Fifty copies only reprinted hy the Academy for the Author.] DUBLIN: PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, BY PONSONBY AND WELDRICK, PKINTBRS TO THB ACAHRMY. 1893 . r 759 ] XXXVIII. STUDIES IN lEISH CKANIOLOGY: THE ARAN ISLANDS, CO. GALWAY.* By PROFESSOR A. C. HADDON. [Eead December 12, 1892.] The following is the first of a series of communications which I pro- pose to make to the Academy on Irish Craniology. It is a remarkable fact that there is scarcely an obscure people on the face of the globe about whom we have less anthropographical information than we have of the Irish. Three skulls from Ireland are described by Davis and Thumam in the “Crania Britannica” (1856-65); six by J. Aitken Meigs in his ‘ ‘ Catalogue of Human Crania in the Collection of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia ” two by J. Van der Hoeven (1857) ; in his “ Catalogus craniorum diversarum gentium” (1860); thirty- eight (more or less fragmentary), and five casts by J. Barnard Davis in the “Thesaurus craniorum” (1867), besides a few others which I shall refer to on a future occasion. Quite recently Dr. W. Frazer has measured a number of Irish skulls. “ A Contribution to Irish Anthropology,” Jour. Roy. Soc. Antiquarians of Ireland, I. (5), 1891, p. 391. In addition to three skuUs from Derry, Dundalk, and Mary’s Abbey, Dublin, Dr. -

PSAI 2014 Programme Final

PSAI Conference 2014: overview Friday 17 October 2014 Type of Session Session title Time Venue PSAI Executive Committee Meeting 12:30- Inishmore 14:00 Arrival and From Foyer (beside Registration 13:00 Inishturk) Parallel Session 1 A. Irish Politics 1 14:00- Inishmore B. Northern Ireland: international 15:30 Inishturk dimensions C. Participatory and Deliberative Inisheer Democracy: theory and praxis Tea/Coffee Break 15:30- 16:00 Parallel Session 2 A. Global Political Society 16:00- Inishmaan B. Dominating Unionism 17:30 Inishturk C. Political Theory Inisheer D. Publishing workshop with Tony Mason, Inishmore Manchester University Press Event 30th anniversary of the PSAI: 18:00- Inisturk Celebration/Book Launch and Roundtable 19:00 Saturday 18 October, 2014 Type of Session Title of Session Time Venue Parallel Session 3 A. Foreign Policy, Middle East and 9:00- Inisheer International Relations 10:30 B. Re-examining the Roman Catholic Inishturk Church’s Role in 20th C. Irish Politics C. Republicanism, Power and the Inishmaan Constitution D. Remembering conflict and educating Inishmore for peace Tea/Coffee break 10:30-11 Parallel Session 4 A. Gendering Politics and Political 11:00- Inisheer Discourse in the National and 12:30 International Arena B. Conflict and Divided Societies 1 Inishmaan C. Northern Ireland after the Peace Inishturk D. Teaching and Learning Inishmore Lunch 12:30- Harvest Cafe 13:30 (up the stairs) PSAI Specialist 12:30- Group Meetings 13:30 1 Plenary Session Peter Mair Memorial Lecture by 13:30- Inishturk Professor Donatella della Porta (European 14:30 University Institute): Political cleavages in times of austerity. -

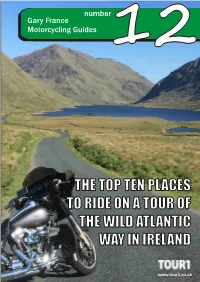

Guide 12 Wild Atlantic

number Gary France Motorcycling Guides 12 THE TOP TEN PLACES TO RIDE ON A TOUR OF THE WILD ATLANTIC WAY IN IRELAND www.tour1.co.uk 1. Doolough Pass The pass is on the R335 road, between Cregganbaun and Delphi, in County Mayo. It Introduction is a good riding road set between scenic mountains and beside a stunning lake. The Wild Atlantic Way is the coast road Doolough Pass is shown on the cover of this on the west coast of Ireland and what a guide. stunning place it is to ride! As it has become more popular in recent years, I have often been asked what are the best parts of the road to ride. Here are my top ten, in order of north to south. Other people may have other thoughts about places that are equally as good, but these are my favourites that I have ridden and seen for myself. 2. Sky Road, Clifden Immediately to the west of Clifden in County Gary France. Galway is Sky Road which runs around a peninsula jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean. The Sky Road route takes you up among the hills overlooking Clifden Bay and its offshore islands, Inishturk and Turbot. Be sure to ride around the whole Sky Road loop and I have found clockwise to be the best direction. www.tour1.co.uk 1 3. The Connemara 5. Connor Pass The Connemara is a district on the west coast Connor Pass runs diagonally across the Dingle of Ireland which runs broadly from Killary Peninsula, in County Kerry. -

Energy Audit on Aran Islands

2015-10-22 ENERGY AUDIT ON THE ARAN ISLANDS Energy audit on the Aran Islands 1 Introduction 2 2 Abstract 3 3 Facts 4 4 The culture and identity of the Aran Island 10 5 Optimism 12 6 Pessimism 12 7 Possibilities 13 8 Action Plan 14 1 (15) ENERGY AUDIT ON THE ARAN ISLANDS Christian Pleijel [email protected] Tel +358-457-342 88 25 ENERGY AUDIT ON THE ARAN ISLANDS 1 Introduction In 2014, the Aran Islands joined the SMILEGOV1 prOject thrOugh its membership in the Comhdháil Oileáin na hÉireann (Irish Islands AssOciatiOn) and subse- quently in the European Small Islands Federation (ESIN). The objectives of SMILEGOV, funded by the IEE at the EurOpean COmmissiOn, is to establish a clear picture Of the island’s energy cOnsumptiOn, its emissiOns and hOw it is it supplied with energy, moving intO an actiOn plan fOr a more sustainable future, and to invite the island to join the Pact of Islands2. 1.1 Process The wOrk has mainly been carried Out by SeniOr AdvisOr Christian Pleijel, fOr- merly at SwecO, nOw an independent cOnsultant and the Vice President Of ESIN (European Small Islands Federation), with the kind help of Mr Ronan MacGiol- lapharaic at the Fuinneamh Oileáin Árann (Aran Islands Energy), support frOm the Irish Islands AssOciatiOn and frOm the Cork County Council. 1.2 Methodology The island has been Observed frOm six different perspectives, a methOd de- scribed and used in Christian Pleijel’s bOOk On the small islands Of EurOpe3: (1) Facts, (2) Identity and culture, (3) Optimism, (4) Pessimism, (5) POssibilities, and (6) ActiOns. -

Telepsychiatry': Keeping a Link with an Island

BRIEFINGS 'Telepsychiatry': keeping a link with an island L Mannion, T.J. Fahy, C. Duffy, M, Broderick and E. Gethins quality. We report on the pilot phase of a video conferencing link between a psychiatric depart ment and an island located within its catchment area. The study The three Aran Islands, Inishmore, Inisheer, and Inishmean, located off the west coast of Ireland, are included as part of a sector area of the West Galway Psychiatric Service. The population of these islands have been greatly affected by emigration. We have estimated that there are 53 psychiatric patients permanently resident on the three islands. The majority of this group suffer from major psychiatric disorders requiring continual monitoring. The population of the Figure 1. Aran Islands. islands increases enormously during the sum mer months due to the influx of tourists. Medical care is provided by one general practitioner (GP). with a public health nurse resident on each Telemedicine' has been defined as the delivery of island. Psychiatric care is provided by periodic health care where the patient and health profes visits by the community services team of the sional are at different locations (McLaren & Ball, West Galway service. An out-patient clinic is held 1995), and in recent years has come to be on the main island, Inishmore, every two months regarded as the use of telecommunications and every three to four months on the smaller technology for medical applications. Telepsy- islands. A community psychiatric nurse (CPN) chiatry' is the branch of 'telemedicine' that visits Inishmore every month and each of the focuses on mental health applications. -

West of Ireland Paintings at the National Gallery of Ireland from 1800 to 2000

West of Ireland Paintings at the National Gallery of Ireland from 1800 to 2000 I The West of Ireland National Gallery of Ireland / Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann West of Ireland Paintings at the National Gallery of Ireland from 1800 to 2000 Marie Bourke With contributions by Donal Maguire And Sarah Edmondson II Contents 5 Foreword, Sean Rainbird, Director, National Gallery of Ireland 23 The West as a Significant Place for Irish Artists Contributions by Donal Maguire (DM), Administrator, Centre for the Study of Irish Art 6 Depicting the West of Ireland in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Dr Marie Bourke, Keeper, Head of Education 24 James Arthur O’Connor (1792–1841), The Mill, Ballinrobe, c.1818 25 George Petrie (1790–1866), Pilgrims at Saint Brigid’s Well, Liscannor, Co. Clare, c.1829–30 6 Introduction: The Lure of the West 26 Frederic William Burton (1816–1900), In Joyce Country (Connemara, Co. Galway), c.1840 6 George Petrie (1790–1866), Dún Aonghasa, Inishmore, Aran Islands, c.1827 27 Frederic William Burton (1816–1900), The Aran Fisherman’s Drowned Child, 1841 8 Timeline: Key Dates in Irish History and Culture, 1800–1999 28 Augustus Burke (c.1838–1891), A Connemara Girl 10 Curiosity about Ireland: Guide books, Travel Memoirs 29 Bartholomew Colles Watkins (1833–1891), A View of the Killaries, from Leenane 10 James Arthur O’Connor (1792–1841), A View of Lough Mask 30 Aloysius O’Kelly (1853–1936), Mass in a Connemara Cabin, c.1883 11 Frederic William Burton (1816–1900), Paddy Conneely (d.1850), a Galway Piper 31 Walter Frederick Osborne (1859–1903), A Galway Cottage, c.1893 32 Jack B. -

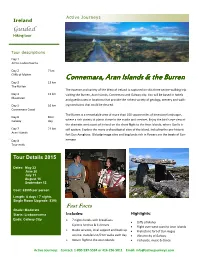

IR Connemara Burren GH.Pub

Active Journeys Ireland Guided Hiking tour Tour descriptions Day 1 Arrive Lisdoonvarna Day 2 7 km Cliffs of Moher Connemara, Aran Islands & the Burren Day 3 13 km The Burren The essence and variety of the West of Ireland is captured on this three centre-walking trip Day 4 13 km vising the Burren, Aran Islands, Connemara and Galway city. You will be based in hotels Maumeen and guesthouses in locaons that provide the richest variety of geology, scenery and walk- Day 5 16 km ing condions that could be desired. Connemara Coast The Burren is a remarkable area of more than 100 square miles of limestone landscape, Day 6 Rest Galway day where a rich variety of plants thrive in the cracks and crevices. Enjoy the bird’s eye view of the dramac west coast of Ireland on the short flight to the Aran Islands, where Gaelic is Day 7 21 km sll spoken. Explore the many archaeological sites of the island, including the pre-historic Aran Islands fort Dun Aonghasa. Old pilgrimage sites and bog lands rich in flowers are the treats of Con- Day 8 nemara. Tour ends Tour Details 2015 Dates: May 23 June 20 July 11 August 15 September 12 Cost: $2095 per person Length: 8 days / 7 nights Single Room Upgrade: $395 Fast Facts Grade: Moderate Starts: Lisdoonvarna Includes: Highlights: Ends: Galway City • 7 nights hotels with breakfasts • Cliffs of Moher 6 picnic lunches & 6 dinners • Flight over west coast to Aran Islands • Guide services, local support and back up • Prehistoric fort of Dun Aegus service, transfers to/from walks each day • Vibrant city of Galway • Return flight to the Aran Islands • Irish pubs, music & dance Acve Journeys Contact: 1-800-597-5594 or 416-236-5011 Email: [email protected] Inerary Day 1 Arrival Arrival at accommodaon in Lisdoonvarna, renowned for tradional Irish music. -

A Case Study of Stone Forts at Cliff-Top Locations in the Aran Islands, Ireland

GEA(Wiley) RIGHT BATCH Short Contribution: Marine Erosion and Archaeological Landscapes: A Case Study of Stone Forts at Cliff-Top Locations in the Aran Islands, Ireland D.Michael Williams Department of Earth and Ocean Sciences, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland Two massively constructed stone forts exist on the edge of vertical coastal cliffs on the Aran Islands, Ireland. One of these, Dun Aonghusa, contains evidence of occupation that predates the main construction phases of the walls and broadly spans a time interval of 3300–2800 yr B.P. The other fort, Dun Duchathair, has been termed a promontory fort because its remaining wall crosses the neck of a small promontory marginal to the cliffs. Estimates of past rates of marine erosion in this part of Ireland may be made both by analogy with studies in other areas and comparison with present day rates of marine erosion. A working model for erosion rates of approximately 0.4m of coastal recession per annum is suggested. By applying this rate to the cliffs of the Aran Islands, it can be shown that, assuming a construction date of approximately 2500 yr B.P. for these forts, they were originally built at a considerable distance from the coastline. Thus Dun Duchathair was not a promontory fort. The earliest recorded habitation at Dun Aonghusa, dated to the middle of the Bronze Age, was, therefore, at some distance inland and not on an exposed 70 m high cliff on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. ᭧ 2004Wiley Periodicals, Inc. INTRODUCTION At a period of widespread rise in relative sea-level in many parts of the world, the present-day landscapes of archaeological sites may be misleading due to marine erosion. -

20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010 - 2030 Progress Report: 2010 - 2015 Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources

20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010 - 2030 Progress Report: 2010 - 2015 Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources During the period covered by this report, the Department has adhered to its commitments set out in its implementation plan under the Strategy and in accordance with the Broadcasting Act 2009. In 2009, with the enactment of the Broadcasting Act 2009, the allocation of licence fee money to the Broadcasting Funding Scheme, of which TG4 is one of the main beneficiaries, was increased from 5% to 7%. The Good Friday Agreement provided that the British Government would work with the relevant British and Irish broadcasting authorities to make TG4 more widely available in Northern Ireland. Following the switchover to digital television in 2012, TG4’s coverage has reached 94% in Northern Ireland. RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta is also being provided on the Northern Ireland Freeview DTT network. In autumn 2014, TG4 launched an upgraded/redesigned TG4 website with major new features for national and global users. An IOS app for iPad and iPhone and a Smart TV app, available for download to all major platforms, was also launched. This ensures access to Irish language programming via multiple devices for a worldwide audience. With the launch in October 2015 of a book and app based on the television series Saol faoi Shráid, TG4 has delivered a multi-platform Irish language puppet series for children. In addition to these formats, TG4 has provided extended children's access to the series with a live puppet show, which toured nationwide and featured in Baboró Kids Festival 2015. -

Terrain of the Aran Islands Karen O'brien

Spring 2006 169 ‘Ireland mustn’t be such a bad place so’: Mapping the “Real” Terrain of the Aran Islands Karen O’Brien Martin McDonagh’s The Cripple of Inishmaan (1996) responds to and encodes the complexities of representational and ecological issues surrounding life on the rural landscape of the Aran Islands. The three islands that constitute the Aran Islands—Inisheer, Inishmaan, and Inishmore—occupy a unique and dual position of marginality and liminality; they not only reside off the border of the western coast of Ireland but also inhabit an indeterminate space between America and Europe. The archipelagos are described by Irish poet Seamus Heaney as a place “Where the land ends with a sheer drop / You can see three stepping stones out of Europe.”1 Inishmaan employs three strategic interrogations—representation, structure, and aesthetics—that coincide with the project of collaborative ecology. The first strategy juxtaposes two contrasting representations of Ireland’s 1930s rural west, problematizing the notion of a definable Irishness in relation to the unique Arans landscape. Inishmaan revolves around the filming of the American documentary Man of Aran (1934), which claims authenticity in its representation of actual island residents. McDonagh’s depiction of the Aran community, however, contradicts the documentary’s poetic vision of the Aran Islands as a pristine landscape. In scene eight, for example, the screening of Man of Aran does not reflect a mirror image of the Aran residents represented in the play; the film, contrarily, incites mockery. Despite its claim of historical authenticity and authority, the documentary proves fictional. Inishmaan contests the legitimacy of Man of Aran explicitly as well as a history of romanticized notions of western Irish identity implicitly. -

Submission Re Application FS006566 for Foreshore Lease in Galway Bay

Submission No. 301 From: Sent: 09 September 2016 09:05 To: foreshore Subject: Submission re application FS006566 for Foreshore Lease in Galway Bay 9 Sept 2016 Dear sir / Madam, I am objecting to the granting of application FS006566, “Application for a Foreshore lease for the construction of an Offshore Electricity Generating Station” for the following reasons; Firstly I have been deprived of an Environmental Impact Statement and as a result I do not have the information I require to assess the impact this development will have on the community and the wellbeing of the local and visiting tourists. Therefore I request that an Environmental Impact Study is conducted and circulated to the community before a decision is made with regards to this application. The impacts of the proposed development on the sensitive area of Galway Bay, its legally protected species and Habitats, have not been Appropriately Assessed as required by law. Ihave not been properly informed and Ihave not been consulted and included in the decision making process with regard to this application as required under the Aarhus Convention. Galway bay is known worldwide and with the Wild Atlantic Way bringing more tourists to the area which generates much needed jobs and income locally I am at a loss to understand why the impact on tourism has not been considered in this application. I am requesting that this is addressed before a decision is made with regards to this application No consideration has been given to the fact that Galway (City and County) has been selected as the European Capital of Culture for 2020.