General Characteristics and Origins of English Idioms with a Proper Name Constituent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theatre of the Absurd : Its Themes and Form

THE THEATRE OF THE ABSURD: ITS THEMES AND FORM by LETITIA SKINNER DACE A. B., Sweet Briar College, 1963 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Speech KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1967 Approved by: c40teA***u7fQU(( rfi" Major Professor il PREFACE Contemporary dramatic literature is often discussed with the aid of descriptive terms ending in "ism." Anthologies frequently arrange plays under such categories as expressionism, surrealism, realism, and naturalism. Critics use these designations to praise and to condemn, to denote style and to suggest content, to describe a consistent tone in an author's entire ouvre and to dissect diverse tendencies within a single play. Such labels should never be pasted to a play or cemented even to a single scene, since they may thus stifle the creative imagi- nation of the director, actor, or designer, discourage thorough analysis by the thoughtful viewer or reader, and distort the complex impact of the work by suppressing whatever subtleties may seem in conflict with the label. At their worst, these terms confine further investigation of a work of art, or even tempt the critic into a ludicrous attempt to squeeze and squash a rounded play into a square pigeon-hole. But, at their best, such terms help to elucidate theme and illuminate style. Recently the theatre public's attention has been called to a group of avant - garde plays whose philosophical propensities and dramatic conventions have been subsumed under the title "theatre of the absurd." This label describes the profoundly pessimistic world view of play- wrights whose work is frequently hilarious theatre, but who appear to despair at the futility and irrationality of life and the inevitability of death. -

GM Gives Support to the District Council

28.2.85 Edinburgh University Student Newspaper-- Labour group leader speaks to inquorate student audience ------Tt1is week GM gives support to the ------in District Council bY AnM McHaughl The issue of Nelson Mandala's nomination as a candidate In next month's Rectorial election has been reopened after Monday's General Meeting which passed unopposed an emergency motion resulting in the Association formally decrying the University's disqualification of Mandela from candidature, and Increasing its active demands for his release from prison. uncovering alegaJ loophOle whkh Also distu$$«1 by lhe 111 who would pet"m;t the nomination. and attended the GM W'(lte motions ,nld hO WttS meetlno w ith lawyett dWing with poUey rtglrd•no lhe to'lowlng day. Ed•nburgh Olstnct Council, ano l"he ~ motion concerned l~ Clmpjlgn lor a Scottish local govemmtnt $1)tnd•ng. and A.wtmbl)'. A tnOCion on sign spuk.ing In la'I0\11 wat L~b<Kir 1anguago had etrea<ty been OislrieL Councillor. Alox Wood. withdrawn, dut to a ehanoe of whowua110w0dtoe.peallbtetuse stance oo the matter by thO of the walvlng or a slanding otdOt cornmluee.. whlch prtvent.s non-membtl.t The motion supporting Mande&. trom speak.lng. He ex.'hOfted the ellc:ited no cM~et nega:ri'Yo.and the A$soe•aUon to suppon Edtnburgh AS THE rtct()('i~l ei'""'Uon l)(opostt, He.non Ebra.hl'm, briefly District Coundl's Ulogal bu6get approtel'lts. Stlldtnteontinues •umm~ up the cue for MtncH:Ia's ~. befOfe the mot)on could lis ccwora~ by ~reat~.ng a nom•noMon to be tccepted ptogrou. -

Chambers Pardon My French!

Chambers Pardon my French! CHAMBERS An imprint of Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd 7 Hopetoun Crescent, Edinburgh, EH7 4AY Chambers Harrap is an Hachette UK company © Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd 2009 Chambers® is a registered trademark of Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd First published by Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd 2009 Previously published as Harrap’s Pardon My French! in 1998 Second edition published 2003 Third edition published 2007 Database right Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd (makers) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, at the address above. You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 0550 10536 3 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 We have made every effort to mark as such all words which we believe to be trademarks. We should also like to make it clear that the presence of a word in the dictionary, whether marked or unmarked, in no way affects its legal status as a trademark. www.chambers.co.uk Designed -

Over Arco Anchetti

Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies si propone come strumento per la rifessione e la discussio- ne interdisciplinare su temi e problemi che riguardano tutti gli aspetti della cultura irlandese. Accanto a contributi critici, la rivista ospita inediti in lingua originale e/o in traduzione italiana, interviste, recensioni, segnalazioni e bibliografe tematiche. SIJIS privilegia ricerche ancora in corso rispetto ad acquisizioni defnitive, ipotesi rispetto a tesi, aperture più che conclusioni. In questa prospettiva ampio spazio è dedicato al lavoro di giovani studiosi e ai risultati anche parziali delle loro ricerche. Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies aims to promote and contribute to the interdisciplinary debate on themes and research issues pertaining to every aspect of Irish culture. Te journal hosts scholarly essays, previously unpublished literary contributions, both in the original language and Ital- ian translation, as well as interviews, reviews, reports and bibliographies of interest for Irish culture scholars. SIJIS gives priority to research in progress focusing on recent developments rather than con- solidated theories and hypotheses, openings rather than conclusions. It encourages young scholars to publish the results of their – completed or ongoing – research. General Editor Fiorenzo Fantaccini (Università di Firenze) Journal Manager Arianna Antonielli (Università di Firenze) Advisory Board Donatella Abbate Badin (Università di Torino), Rosangela Barone (Istituto Italiano di Cultura-Trinity Col- lege, Dublin), Zied Ben Amor (Université de Sousse), Melita Cataldi (Università di Torino), Richard Allen Cave (University of London), Manuela Ceretta (Università di Torino), Carla De Petris (Università di Roma III), Emma Donoghue (novelist and literary historian), Brian Friel (playwright), Giulio Giorello (Università di Milano), Rosa Gonzales (Universitat de Barcelona), Klaus P.S. -

1999 Proceedings of the Casualty Actuarial Society, Volume LXXXVI

VOLUME LXXXVI NUMBERS 164 AND 165 PROCEEDINGS OF THE Casualty Actuarial Society ORGANIZED 1914 1999 VOLUME LXXXVI Number 164—May 1999 Number 165—November 1999 COPYRIGHT—2000 CASUALTY ACTUARIAL SOCIETY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Library of Congress Catalog No. HG9956.C3 ISSN 0893-2980 Printed for the Society by United Book Press Baltimore, Maryland Typesetting Services by Minnesota Technical Typography, Inc. St. Paul, Minnesota FOREWORD Actuarial science originated in England in 1792 in the early days of life insurance. Because of the technical nature of the business, the first actuaries were mathematicians. Eventually, their numerical growth resulted in the formation of the Institute of Actuaries in England in 1848. Eight years later, in Scotland, the Faculty of Actuaries was formed. In the United States, the Actuarial Society of America was formed in 1889 and the American Institute of Actuaries in 1909. These two American organizations merged in 1949 to become the Society of Actuaries. In the early years of the 20th century in the United States, problems requiring actuarial treat- ment were emerging in sickness, disability, and casualty insurance—particularly in workers compensation, which was introduced in 1911. The differences between the new problems and those of traditional life insurance led to the organization of the Casualty Actuarial and Statistical Society of America in 1914. Dr. I. M. Rubinow, who was responsible for the Society’s forma- tion, became its first president. At the time of its formation, the Casualty Actuarial and Statistical Society of America had 97 charter members of the grade of Fellow. The Society adopted its present name, the Casualty Actuarial Society, on May 14, 1921. -

James Red Dog Set to Die July 17

In Sports In Section 2 An Associated Collegiate Press Four-Star All-American Newspaper Men's lacrosse 'The Babe' f~lls to UMass, strikes out 18-11 in two hours . page 85 page 81 FREE TUESDAY The meter expires for Academy Street good Samaritan meters," said Capt. Tom Penoza of the He said the parking officer told him he "I kept asking what I did to hinder the understand why they were ticketed because !rm?n':t~~~ror Newark: Police. could not leave until a Newark police officer officer," Kamrnarman said. "I didn't know it there was still time left on the meter. Because he tried to keep one step ahead of At first it was only 20 cents worth of arrived on the scene to issue a ticket. was against the law. Who would?" When he was allowed to leave the scene the Newark Police, Mike Kamrnarman (AG trouble. "If it's a crime to be a good Samaritan, Unluckily for Karrunannan, the police did . Kammarman said he called the Newark SO) may end up one step behind. But when he decided to put dimes in the then I'm guilty," said Kammarrnan . Penoza said Kammarman interfered with police and the Deputy City Solicitor Mark Last Wednesday, when Kammannan was two meters, the parking enforcement officer Kammarman violated Article III, section the police by puuing money in expired meters Sisk to complain. walking along Academy Srreet, he decided to present did not think his actions were so kind. 20-13 of the Newark Municipal Code which before the officer could write the ticket. -

Rape in South Africa

RAPE IN SOUTH AFRICA THE EXPERIENCES OF WOMEN WHO HAVE BEEN RAPED BY A “KNOWN PERSON”. A CASE STUDY OF WOMEN AT A SHELTER IN JOHANNESBURG. Corey Sarana Spengler A dissertation submitted to the Wits School of Sociology, Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Sociology. Johannesburg 2012/2013 Sociology MA by Dissertation: Ms Corey Spengler Copyright Notice: The copyright of dissertation vests in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, in accordance with the University’s Intellectual Property Policy. No portion of the text may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including analogue and digital media, without prior written permission from the University. Extracts of or quotations from this dissertation may, however, be made in terms of Sections 12 and 13 of the South African Copyright Act No. 98 of 1978 (as amended), for non-commercial or educational purposes. Full acknowledgement must be made to the author and the University. An electronic version of this dissertation is available on the Library webpage (www.wits.ac.za/library) under “Research Resources”. For permission requests, please contact the University Legal Office or the University Research Office (www.wits.ac.za). i Sociology MA by Dissertation: Ms Corey Spengler Title Page: Name: Corey Sarana Spengler Student Number: 0312348G Subject: Masters in Sociology by Dissertation Course Code: SOCL8003 Supervisor: Dr Terry-Ann Selikow (PhD) Research Topic: Rape in South Africa Research Question: The experiences of women who have been raped by a “known person”. -

Myth in the Heroic Comic-Book: a Reading of Archetypes from the Number One Game and Its Models

Myth in the Heroic Comic-book: a reading of archetypes from The Number One Game and its models Robert A.C. Birch Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Visual Arts Stellenbosch University December 2008 Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 10 December 2008 Copyright © 2008 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Summary Title: Mythic Formulations in the Heroic Comic-book: a reading of archetypes from The Number One Game and its models This thesis considers the author's project submission, a comic-book entitled The Number One Game, as production of a local heroic myth. The author will show how this project attempts to engage with mythic and archetypal material to produce an entertaining narrative that has relevance to contemporary Cape Town. The narrative adapts previous incarnations of the hero, with reference to theories of archetypes and mythic patterning devices that are derived from the concept of the “mono-myth”. Joseph Campbell's conception of myth as expressing internal psychic processes will be compared to Roland Barthes' reading of myth as a special inflection of speech that forms a semiotic “metalanguage”. The comic-book is a specific form of the language of comics, a combination of image and text that is highly structured and that can produce a rich graphic text. -

OCTOBER 2019 JANUARY 2020 Key for Show Genres Cabaret Music Theatre Musical Theatre Comedy Spoken Word NB

OCTOBER 2019 JANUARY 2020 Key for show genres Cabaret Music Theatre Musical Theatre Comedy Spoken Word NB. these categories are for guidance only. Some shows may crossover different genres and/or be more difficult to classify. Please refer to the end of this brochure for a full calendar of events. BOOKING INFORMATION Book tickets online www.LiveAtZedel.com or by telephone 020 7734 4888 Show dates and times are subject to change. Please always check the website for details. /LiveAtZedel /LiveAtZedel Jason Gardiner’s image courtesy of David Venni / Chilli Media RESIDENCIES THE JAY RAYNER QUARTET SHOW DATES & TIMES VARY £20 The renowned restaurant critic, MasterChef judge and presenter of BBC Radio 4’s The Kitchen Cabinet, Jay Rayner, returns to Crazy Coqs with The Jay Rayner Quartet: Songs of Food and Agony. This ensemble of top-flight musicians will perform tunes from the Great American food and drink songbook including Cantaloupe Island, Black Coffee, One for My Baby, and Save The Bones. There will be standards from the likes of | ONLINE TICKETS BOOK Johnny Mercer, Harold Arlen, Blossom Dearie and Dave Frishberg. Alongside anecdotes from his life being paid to eat out on somebody else’s dime, he also talks about growing up with a mother, Claire Rayner, who was an agony aunt and plays tunes that draw on the narratives of the problem page letter. With the singer Pat Gordon Smith, bassist Robert Rickenberg and saxophonist Dave Lewis. WWW.LIVEATZEDEL.COM BLACK CAT CABARET “SALON DES ARTISTES” MOST SATURDAYS EVERY MONTH | 9.15PM £32.50 The Black Cat presents “Salon Des Artistes” - an intimate evening of variety from London’s cabaret trailblazers, and the audacious petite soeur to the company’s full-scale theatrical productions. -

The Lowell Ledger. T

Ten Ten es Images This This AVeek. THE LOWELL LEDGER. Week. INDEPENDENT NOT NEUTRAL. ?0L. XIII, NO. 13 OFFICIAL PAPER liOWEIiL, MICH MIAN. TIIURHDAV, SEPTKMHKK 14, 1905 AVKHAdE CIRCUIiATION IN 1904 1359 MARKS AT HOIE AGAIN In the Handsomest Stores in All of HEARD ABOUT RespMsAlllfj Nichiqan. Pay With Checks Marks got ids goods Into Ids hand- mmw some new store yesterday and the FARMERS day before—load after load as big as Last week of Smith's shoe sale. a ton of hay; and it took a smaH S^ee Godfrey's adv. on iiack page. A checking- account is a gfrcat army of people to unpack them and convenience to every one. get them into the store. As for get- Mrs. 1. Mitchell was In Grand Rap- ids Tuesday. Treat Your Seed Wheat with Formalin We will be gflad to assist you ting them into order for exhibition, Mrs. A M. Barnes is visiting her in starting one. that Is a matter that will keep many cister at Ovid. Come in and ask us about it. hands busy day and night until next Bargain prices on Foster grocery Thursday evening when the exhibl. stock at VanDyke's. See adv. tion starts. Thursday evening and Work Is progreflsltig on Mrs. A. J. Formalin is a sure preventative Friday are reception days and there Lewis' new house on Monroe street. will be souvenirs for the first 500 Mrs. Olive Caldwell returned Sun- of smut 'and is recommenned Ivy The City Bank, day from a visit with friends at Ada. visitors. -

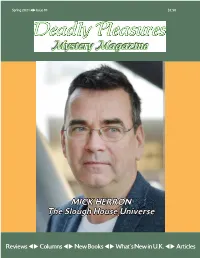

Mick Herron's Slough House Universe

Spring 2021WX Issue 91 $2.50 Deadly Pleasures Mystery Magazine MICK HERRON The Slough House Universe Reviews WX Columns WX New Books WX What’s New in U.K. WX Articles 2 Deadly Pleasures Mystery Magazine ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Mick Herron’s Slough House Universe uch like the best sci-fi writers, Spy. When you get right down to it, the MMick Herron has created an series is about fascinating people and ever-expanding universe with its own how they interact, with a bit of danger unique language, which fi nds at its thrown in to spice things up. Th at is why center two buildings – Regent’s Park it has become so popular with readers and Slough House. In Regent’s Park, it with a wide range of tastes – and not is the best of times; in Slough House, it just spy fi ction afi cionados. Novellas is the worst of times. Regent’s Park is Th ese all feature John Batchelor, a where the elite of Britain’s MI5 intelli- Mick Herron’s Slough milkman (babysitter of retired spies). gence service is housed. All its members Th e List (2015). Dieter Hess, an aged are seemingly ambitious and have clear House Bibliography spy, is dead, and John Bachelor, his MI5 paths to climb, but at Slough House, handler, is in deep, deep trouble. Death where MI5 sends its rejects and screw- Novels (Plot summaries can be has revealed that the deceased had been ups, there is a general malaise and a found below in the individual reviews of keeping a secret second bank account— feeling of utter failure – a hole that there the books) and there’s only ever one reason a spy is no climbing out of. -

Gillies Phd Final 2019

Clamouring to be heard: a critique of the forgotten voices genre of social history of the early twenty-first century Midge Gillies Critical essay PhD by Publication The University of East Anglia School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing September 2018 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Word Count: 21,992 (1,376 additional words in the Appendix and 252 in the Acknowledgements) 1 ABSTRACT Forgotten Voices of the Great War by Max Arthur (in association with the Imperial War Museum), (London: Ebury Press, 2002) sold over 250,000 copies and was the first of a series of fourteen forgotten voices books that used first-hand accounts from the Imperial War Museum’s Sound Archive. Their commercial success spawned a raft of publications that promised to introduce readers to the authentic experiences of men and women who had survived major conflicts in the twentieth century. This thesis will argue that, while the books expose individual lives that might otherwise be overlooked, the narrative structure serves to flatten out, rather than amplify, personal testimony. The books largely fail to explore how an interviewee’s experience was shaped by wider geo-political pressures or considerations of gender, rank, geography and age and how events influenced the narrator’s subsequent life. This thesis argues that, while my work has been subject to the same commercial considerations as the forgotten voices books, I have, nevertheless, developed a form of oral history that can be ‘popular’ but mindful of the complex intellectual demands, conundrums and opportunities of oral history.