Gated Communities and Neighborhood Livability In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highlights of Qatar; Places to Visit, Things to Do, Where to Eat?

Highlights of Qatar; Places to visit, things to do, where to eat? There are a number of attractions and activities within easy reach of the Marriott Marquis Hotel: we are highlighting some here for your convenience. During the conference, you may also ask our volunteers who will be around to make your visit most memorable. Looking forward to welcoming you in Qatar, Ilham Al-Qaradawi; 9ICI Chair Hotspots and Highlights Doha Corniche (10 minutes) A seven-kilometre long waterfront promenade around Doha Bay, the Corniche offers spectacular views of the city, from the dramatic high-rise towers of the central business district to the bold shapes of the Museum of Islamic Art. Traditional wooden dhows lining the Bay evoke echoes of Qatar’s great seafaring past. The Corniche provides a green, vehicle-free pedestrian space in the heart of the capital. Katara (10 minutes) An innovative interpretation of the region’s architectural heritage, this purpose- built development’s impressive theatres, galleries and performance venues stage a lively year-round programme of concerts, shows and exhibitions. Among Katara’s recreational attractions are a wide choice of dining options, including top class restaurants offering a variety of cuisines, and a spacious, well- maintained public beach with water sports. The Pearl (10 minutes) The Pearl-Qatar is a man-made island off the West Bay coast featuring Mediterranean-style yacht-lined marinas, residential towers, villas and hotels, as well as luxury shopping at top brand name boutiques and showrooms. A popular dining spot, its waterfront promenades are lined with cafes and restaurants serving every taste – from a refreshing ice cream to a five-star dining experience. -

Qatar 2022 Overall En

Qatar Population Capital city Official language Currency 2.8 million Doha Arabic Qatari riyal (English is widely used) Before the discovery of oil in Home of Al Jazeera and beIN 1940, Qatar’s economy focused Media Networks, Qatar Airways on fishing and pearl hunting and Aspire Academy Qatar has the third biggest Qatar Sports Investments owns natural gas reserves in the world Paris Saint-Germain Football Club delivery of a carbon-neutral tournament in 2022. Under the agreement, the Global Carbon Trust (GCT), part of GORD, will Qatar 2022 – Key Facts develop assessment standards to measure carbon reduction, work with organisations across Qatar and the region to implement carbon reduction projects, and issue carbon credits which offset emissions related to Qatar 2022. The FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ will kick off on 21 November 2022. Here are some key facts about the tournament. Should you require further information, visit qatar2022.qa or contact the Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy’s Tournament sites are designed, constructed and operated to limit environmental impacts – in line with the requirements Media Team, [email protected]. of the Global Sustainability Assessment System (GSAS). A total of nine GSAS certifications have been awarded across three stadiums to date: 21 November 2022 – 18 December 2022 The tournament will take place over 28 days, with the final being held on 18 December 2022, which will be the 15th Qatar National Day. Eight stadiums Khalifa International Stadium was inaugurated following an extensive redevelopment on 19 May 2017. Al Janoub Stadium was inaugurated on 16 May 2019 when it hosted the Amir Cup final. -

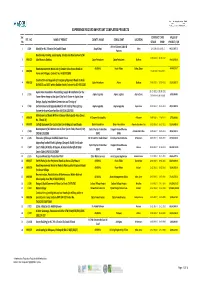

Experience Record Important Completed Projects

EXPERIENCE RECORD IMPORTANT COMPLETED PROJECTS Ser. CONTRACT DATE VALUE OF REF . NO . NAME OF PROJECT CLIENT'S NAME CONSULTANT LOCATION No STRART FINISH PROJECT / QR Artline & James Cubitt & 1 J/149 Masjid for H.E. Ghanim Bin Saad Al Saad Awqaf Dept. Dafna 12‐10‐2011/31‐10‐2012 68,527,487.70 Partners Road works, Parking, Landscaping, Shades and Development of Al‐ 22‐08‐2010 / 21‐06‐2012 2 MRJ/622 Jabel Area in Dukhan. Qatar Petroleum Qatar Petroleum Dukhan 14,428,932.00 Road Improvement Works out of Greater Doha Access Roads to ASHGHAL Road Affairs Doha, Qatar 48,045,328.17 3 MRJ/082 15‐06‐2010 / 13‐06‐2012 Farms and Villages, Contract No. IA 09/10 C89G Construction and Upgrade of Emergency/Approach Roads to Arab 4 MRJ/619 Qatar Petroleum Atkins Dukhan 27‐06‐2010 / 10‐07‐2012 23,583,833.70 D,FNGLCS and JDGS within Dukhan Fields,Contract No.GC‐09112200 Aspire Zone Foundation Dismantling, Supply & Installation for the 01‐01‐2011 / 30‐06‐2011 5 J / 151 Aspire Logistics Aspire Logistics Aspire Zone 6,550,000.00 Tower Flame Image at the Sport City Torch Tower in Aspire Zone Extension to be issued Design, Supply, Installation.Commission and Testing of 6 J / 155 Enchancement and Upgrade Work for the Field of Play Lighting Aspire Logestics Aspire Logestics Aspire Zone 01‐07‐2011 / 25‐11‐2011 28,832,000.00 System for Aspire Zone Facilities (AF/C/AL 1267/10) Maintenance of Roads Within Al Daayen Municipality Area (Zones 7 MRJ/078 Al Daayen Municipality Al Daayen 19‐08‐2009 / 11‐04‐2011 3,799,000.00 No. -

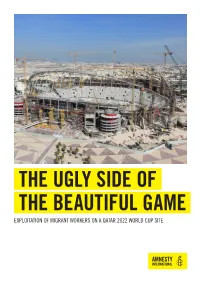

The Ugly Side of the Beautiful Game Exploitation of Migrant Workers on a Qatar 2022 World Cup Site

THE UGLY SIDE OF THE BEAUTIFUL GAME EXPLOITATION OF MIGRANT WORKERS ON A QATAR 2022 WORLD CUP SITE 1 Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Qatar, DOHA - JANUARY 31, 2016: A general view of cranes and building works during the construction and refurbishment of the Khalifa International Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under Stadium in the Aspire Zone, Doha, Qatar, the venue for group and latter stage a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, matches for the 2022 FIFA World Cup. international 4.0) license. © Mathew Ashton - AMA/Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons lisence. First published in 2016 Index: MDE 22/3548/2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Original language: English Peter Benson House, 1 Easton Street Printed by Amnesty International, London WC1X ODW, UK International Secretariat, UK 2 amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.1 Methodology 11 2. BACKGROUND 13 3. LABOUR EXPLOITATION AT KHALIFA INTERNATIONAL STADIUM – A WORLD CUP SITE 16 4. -

'Qatar Stays Firmly on Right Fitness Track'

WEDNESDAY, JuNE 15, 2016 VOLuME XI ISSuE NO.19 QR2.00 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com P 4 | FOOTBALL P 24 | RAMADAN EVENTS JAISH TO MEET NASR PEERLESS PASSION QATAR’S FIRST Qatar’s El Jaish will lock horns with The Salah Saqr football tourney, which ENGLISH SPORTS the UAE’s Al Nasr in the AFC began 42 years ago as an amateur WEEKLY Champions League quarterfinal. event, withstands the test of time. FOLLOW US streetwisePAGES 8-17 P 20 | POSTER LUKA MODRIC P 27 | MOTORSPORT P 28 | RUGBY Rakan makes ‘Qatar stays firmly on DSP EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW the hard tackle right fitness track’ REUTERS/ Kai Pfaffenbach UK £1, Europe €2 | Oman 200 Baisas | Bahrain 200 Fils | Egypt LE 2 | Lebanon 3,000 Livre | Kuwait 250 Fils | Morocco Dh 6 | UAEDh 5 | Yemen 75 Riyals | Sudan 1 Pound | KSA 2 Riyals | Jordan 500 Fils | Iraq $1 | Palestine $1 | Syria LS 20 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com | Wednesday, June 15, 2016 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com 3 EXCITEMENT NOW JUST A TOUCH AWAY OutlookThe writer can be contacted at [email protected] Wherever we’re, always respect local culture and traditions ĈĈThe main topic of discussion at bottles and chairs and forcing volleys of tear gas It may be recalled that a section of the western Euro 2016 remains hooligans from riot police, making the streets look like a media had constantly criticised Qatar, often with battlefield. a sense of sarcasm too, saying the 2022 World Cup ITH five days into Euro 2016, I’m bit- The UEFA on Tuesday threatened to throw Russia could be the most sober ever, citing the restric- terly disappointed to note that unruly out of the tournament as the European govern- tions prevailing in our country vis-à-vis the avail- Wfans and crowd disturbances have ing body imposed a suspended disqualification ability and consumption of alcohol. -

How Can Qatar Land Its Sporting Strategy?

SPECIAL REPORT | QATAR Up in the air: how can Qatar land its sporting strategy? Qatar is well on the way to becoming an international sports superpower. An investor in a string of global properties and an increasingly prominent host of major events, the tiny state is already preparing to stage the 2022 Fifa World Cup, amidst a swell of controversy and no little bewilderment. SportsPro, with the help of experts from a variety of fields, looks at the five keyquestions facing Qatar as it prepares for its most important decade. By David Cushnan and James Emmett How do you intend to build and use mass of just over 11,500 square kilometres, and no little bewilderment. There may ten to 12 World Cup stadiums in a with the vast majority located in and be few real doubts about Qatar’s ability country of 1.9 million people? around the capital city, Doha, on the east to build the ten to 12 stadiums required coast. The decision to award Qatar the \ In 2022, Qatar will stage the most tournament, following a Fifa Executive \ compact Fifa World Cup in history. Just 1.9 Committee vote in December 2010, has presents a far greater challenge for local million people live in a state with a land \ organisers and Qatar’s rulers. 94 | www.sportspromedia.com SportsPro Magazine | 95 SPECIAL REPORT | QATAR Qatar’s 2022 Fifa World Cup stadium plan (as per 2010 bid) Al-Gharafa Stadium Khalifa International Stadium Location: Al- Location: Al- Rayyan Rayyan Capacity: 44,740 Capacity: 68,030 Cost: US$135 Cost: US$71 million million Matches: Group Matches: Group matches, -

Event ID: 14997 DIRECTIVES

FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE GYMNASTIQUE th 11 FIG Artistic Gymnastics Individual Apparatus World Cup Doha / Qatar 21 - 24 March 2018 DIRECTIVES Event ID: 14997 Dear FIG affiliated Member Federation, Following the decision of the FIG Executive Committee, the Gymnastics Federation of Qatar has the pleasure to invite your Federation to participate in the aforementioned official FIG Individual Apparatus World Cup. FIG Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG) Contact Person : Terhi Toivanen Avenue de la Gare 12 1003 Lausanne Switzerland Tel : +41 (0)21 321 55 10 / Direct +41 (0)21 321 55 33 Fax: +41 (0)21 321 55 19 e-mail : [email protected] website: www.fig-gymnastics.com HOST FEDERATION Qatar Gymnastics Federation Contact Person: Anis Saoud 5th floor at Al-Bedaa tower, Al-Dafna – Doha P.O. Box: 22955 Doha-Qatar Tel: +974 44944133 Fax: +974 44944131 e-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.qatargym.com Web site of the event: www.dohagym.com LOCATION Doha, Qatar DATES From March 21 to 24, 2018 VENUE Aspire Academy Dome Tel: +974 44136000 Fax: +974 44136060 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.aspire.qa The Training Hall and Warm-up Halls will be located at the same place. APPARATUS A detailed list of Spieth equipment to be used for this FIG Individual Apparatus SUPPLIER World Cup will be published on the FIG web site RULES AND The competition will be organized under the following FIG rules, as valid in the REGULATIONS year of the competition, except for any deviation mentioned in the Rules for Individual Apparatus -

Schools Are Safe, No Reason to Fear Or Worry

QatarTribune Qatar_Tribune TUESDAY QatarTribuneChannel qatar_tribune SEPTEMBER 8, 2020 MUHARRAM 20, 1442 VOL.14 NO. 5046 QR 2 Fajr: 3:59 am Dhuhr: 11:32 am Asr: 3:00 pm Maghrib: 5:47 pm Isha: 7:17 pm Business 9 Sports 13 MoCI, QC sign MoU Djokovic says ‘so sorry’ FINE to issue Arab but feels shouldn’t have HIGH : 42°C e-certificate of origin been disqualified LOW : 30°C COVID-19 recoveries surpass 117,000 Schools are safe, TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK DOHA no reason to fear QATAR on Monday reported 253 corona- virus (COVID-19) cases -- 233 from com- munity and 20 from travellers returning from abroad, the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) said in its daily report. or worry: Official Also, 243 people recovered from the virus in the past 24 hours, bringing the total number of recoveries in Qatar to 85% attendance 117,241. Sadly, two more people – aged 71 and 76 – succumbed to the virus, tak- in most schools ing the death toll in the country to 205. TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK The MoPH said all the new cases DOHA have been introduced to isolation and are receiving necessary healthcare ac- THE number of coronavirus cases re- cording to their health status. ported in schools is very few and there is no reason to fear or worry, a senior ministry official has said. The schools are safe for children, he added. “Among more than 340,000 stu- dents and 30,000 teachers in schools, Continuous coordination between the QRCS PROVIDES HUMANITARIAN AID the number of cases that have been Ministry of Education and Higher Educa- confirmed to have coronavirus is very tion and the Ministry of Public Health to TO HELP SUDAN FIGHT COVID-19 few,” Mohamed Al Bishri, an advi- ensure safety in schools. -

Aspire Zone-Phase II

Aspire Zone-Phase II Client Location Aspire Zone Foundation Doha, Qatar Types of Activities Scope of Work Master planning Architectural Pre-concept design Civil Design optimization Communications & security systems Basis of design report (BODR) Electrical Landscaping Roads Urban design With an area of approximately 1.7 million square meters, Aspire Zone-Phase II is also envisioned to encompass a Aspire Zone-Phase II is intended to be developed as a sustainable and flexible park surrounding the continuous mixed-use development that includes the following areas: pedestrian pathway linking the whole site. The park is • Residential area: single & multi-family units designed to add a cultural, economic, and aesthetic value • Commercial area: offices, restaurants, and business to the surroundings, with a lake enfolding the main spine parks and the central zones. • Community area: mosques and schools • Recreational facilities: main spine & open parking As Qatar gears up for the FIFA 2022 World Cup, this space development will also be designed to include training sites for the FIFA-complaint team base camps. For the The site of Phase II, which is located near the site of Phase tournament phase, the overall master planning introduces I, is close to Doha Corniche and is connected to Doha safety measures aiming to secure the team base camps through major modes of transportation. It is currently and training sites in line with FIFA regulations. After the home to two heritage sites that have been preserved tournament, the commercial avenue and business parks during the overall master planning. will be further developed with the highest standards. Aspire Zone-Phase II. -

Over 340,000 Students to Attend New Academic Year

www.thepeninsula.qa Tuesday 1 September 2020 Volume 25 | Number 8367 13 Muharram - 1442 2 Riyals BUSINESS | 13 PENMAG | 15 SPORT | 20 Doha Bank, Classifieds QFA reveals ICSS unite to and Services competition promote skills section roadmap ahead of development included new football season Choose the network of heroes Enjoy the Internet Over 340,000 students to attend new academic year THE PENINSULA — DOHA year will be very successful and students’ cognitive concepts fruitful for all of us, adding: “Based and strengthens the educational Minister of Education and Dear students and parents, on COVID-19 infection rates in values and principles of human Higher Education, H E Dr. Qatar and driven by our belief in interaction. Mohammed bin Abdulwahed It gives me great pleasure to the importance of resuming the “In parallel, blended learning Ali Al Hammadi, has said that congratulate you on the new education process, the Ministry of will help realise the advantages over 340,000 students will Education and Higher Education, of distance learning. Most attend public and private academic year. I am pretty sure in close coordination with the importantly, it will allow stu- schools for the academic year that this year will be very Ministry of Public Health, decided dents to develop and use IT of 2020/21 which will begin to implement the ‘blended skills. It will also build students’ today. The Ministry has opened successful and fruitful for all of us. learning’ approach, which com- sense of responsibility as well as new public and private schools bines online and classroom-based innovation and creativity capa- and expanded capacity of H E Dr. -

Team Manual Ww

TEAM MANUAL WW GENERAL INFORMATION ● Aspire Zone Warm-up Area – Throwing Events 39 MEDICAL SERVICES ● IAAF Council Members, Delegates and ● Team Leaders’ Orientation Tour and ● Emergency Contact Numbers 63 International Officials 5 Athletes training - Khalifa Stadium 39-40 ● Medical Services in Venue Medical Centres 63 ● Local Organising Committee 7 ● Sports Equipment 40 Khalifa Stadium 64 ● Information About Host Country and City 8 ● Vaulting Pole 40 Warm-up Area 65 ● Host Country 8-9 ● Markers (Runways) 41 ● Khalifa Stadium Warm-up Area – ● Host City 11 ● Implements 41 Running and Jumping Events 65 ● Key Dates and General Programme 14-15 ● Aspire Dome Indoor Warm-up Area - ENTRY QUALIFICATION SYSTEM AND Running and Jumping Events 65 TRAVEL TO DOHA FINAL CONFIRMATIONS ● Aspire Zone and Warm-up Area - ● Arrivals and Departures 17 ● Athletes’ Entries and Qualification 43 Throwing Events area 65 ● Visas 17 ● Age Categories 43 ● Doha Corniche: Marathon and Race Walks 65 ● Entry Rules 43 Team Hotels 66 ACCREDITATION ● Qualification System 43 Training Venue 66 ● Accreditation Centres 18 ● Qualification Period 43 ● Qatar Sports Club 66 ● Accreditation Procedures and Payments 19 ● Individual Athletes 43-44 ● Designated Medical Institutions 66 ● Special Passes 19 ● Relay Teams 44 Aspetar Orthopedic and Sports ● Loss of Accreditation Card 19 ● Unqualified Athletes 45 medicine Hospital Services 66=67 ● Extra Coach Package 19 ● Target Number of Athletes/Teams by Event 45 ● Hamad General Hospital 67 ● Entry Standards 46 ● Medical Delegate and Procedures -

Sheikha Moza Attends Unveiling of 'Seeroo Fi Al Ardh'

16 Thursday, December 12, 2019 The Last Word Sheikha Moza attends unveiling of ‘Seeroo fi al Ardh’ to knowledge, discovery and The artwork at QF understanding, and that it is the final creation should be open to all.” Najma Husain, the late of M F Husain artist’s daughter-in-law, told the ceremony, “I am hon- TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK oured and extremely grateful DOHA to be here for his dream pro- ject. M F Husain walked the HER HIGHNESS Sheikha earth teaching us to appreci- Moza bint Nasser, Chair- ate life. It is amazing how his person of Qatar Foundation art survived catastrophes, (QF), on Wednesday attend- and it taught us to appreciate ed a celebration to reveal the the visual language of art.” ‘Seeroo fi al Ardh’, the final The guests then wit- work of the late world-re- nessed the first performance nowned artist Maqbool Fida of the Seeroo fi al Ardh’s Husain, at Education City. main show, which reflects The Seeroo fi al Ardh is how the ambitions of peo- part of a wide-ranging pro- ple throughout the Arab re- ject chronicling the journey HH Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, Chairperson of Qatar Foundation, unveiled the last artwork by the late Indian artist M F Husain, ‘Seeroo fi al Ardh’, which was commissioned by gion were advanced first by of human civilisation through Her Highness in 2009 along with an extensive collection of artworks on the progression of human civilisation through the history of the Arab region. (AISHA AL-MUSALLAM) nature, then by machines, the lens of the Arab region’s and how the Arab world was history that was undertaken ful, the Compassionate.