Texas Law Review See Also [Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valuation of NFL Franchises

Valuation of NFL Franchises Author: Sam Hill Advisor: Connel Fullenkamp Acknowledgement: Samuel Veraldi Honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation with Distinction in Economics in Trinity College of Duke University Duke University Durham, North Carolina April 2010 1 Abstract This thesis will focus on the valuation of American professional sports teams, specifically teams in the National Football League (NFL). Its first goal is to analyze the growth rates in the prices paid for NFL teams throughout the history of the league. Second, it will analyze the determinants of franchise value, as represented by transactions involving NFL teams, using a simple ordinary-least-squares regression. It also creates a substantial data set that can provide a basis for future research. 2 Introduction This thesis will focus on the valuation of American professional sports teams, specifically teams in the National Football League (NFL). The finances of the NFL are unparalleled in all of professional sports. According to popular annual rankings published by Forbes Magazine (http://www.Forbes.com/2009/01/13/nfl-cowboys-yankees-biz-media- cx_tvr_0113values.html), NFL teams account for six of the world’s ten most valuable sports franchises, and the NFL is the only league in the world with an average team enterprise value of over $1 billion. In 2008, the combined revenue of the league’s 32 teams was approximately $7.6 billion, the majority of which came from the league’s television deals. Its other primary revenue sources include ticket sales, merchandise sales, and corporate sponsorships. The NFL is also known as the most popular professional sports league in the United States, and it has been at the forefront of innovation in the business of sports. -

Case Studies in Forensic Physics Gregory A

DILISI • RARICK • DILISI Case Studies in Forensic Physics Gregory A. DiLisi, John Carroll University Richard A. Rarick, Cleveland State University This book focuses on a forensics-style re-examination of several historical events. The purpose of these studies is to afford readers the opportunity to apply basic principles of physics to unsolved mysteries STUDIESCASE IN PHYSICS FORENSIC and controversial events in order to settle the historical debate. We identify nine advantages of using case studies as a pedagogical approach to understanding forensic physics. Each of these nine advantages is the focus of a chapter of this book. Within each chapter, we show how a cascade of unlikely events resulted in an unpredictable catastrophe and use introductory-level physics to analyze the outcome. Armed with the tools of a good forensic physicist, the reader will realize that the historical record is far from being a set of agreed upon immutable facts; instead, it is a living, changing thing that is open to re-visitation, re-examination, and re-interpretation. ABOUT SYNTHESIS This volume is a printed version of a work that appears in theSynthesis Digital Library of Engineering and Computer Science. Synthesis Lectures provide concise original presentations of important research and development topics, published quickly in digital and print formats. For more information, visit our website: http://store.morganclaypool.com MORGAN & CLAYPOOL store.morganclaypool.com Case Studies in Forensic Physics Synthesis Lectures on Engineering, Science, and Technology Each book in the series is written by a well known expert in the field. Most titles cover subjects such as professional development, education, and study skills, as well as basic introductory undergraduate material and other topics appropriate for a broader and less technical audience. -

Patriots at Philadelphia Game Notes

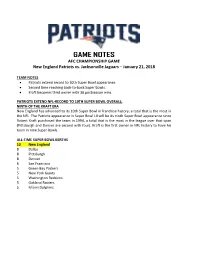

GAME NOTES AFC CHAMPIONSHIP GAME New England Patriots vs. Jacksonville Jaguars – January 21, 2018 TEAM NOTES Patriots extend record to 10th Super Bowl appearance. Second time reaching back-to-back Super Bowls. Kraft becomes third owner with 30 postseason wins. PATRIOTS EXTEND NFL-RECORD TO 10TH SUPER BOWL OVERALL; NINTH OF THE KRAFT ERA New England has advanced to its 10th Super Bowl in franchise history, a total that is the most in the NFL. The Patriots appearance in Super Bowl LII will be its ninth Super Bowl appearance since Robert Kraft purchased the team in 1994, a total that is the most in the league over that span (Pittsburgh and Denver are second with four). Kraft is the first owner in NFL history to have his team in nine Super Bowls. ALL-TIME SUPER BOWL BERTHS 10 New England 8 Dallas 8 Pittsburgh 8 Denver 6 San Francisco 5 Green Bay Packers 5 New York Giants 5 Washington Redskins 5 Oakland Raiders 5 Miami Dolphins PATRIOTS IN THE SUPER BOWL (5-4) Date Game Opponent W/L Score 01/26/86 XX Chicago L 10-46 01/26/97 XXXI Green Bay L 21-35 02/03/02 XXXVI St. Louis W 20-17 02/01/04 XXXVIII Carolina W 32-29 02/06/05 XXXIX Philadelphia W 24-21 02/03/08 XLII New York Giants L 14-17 02/05/12 XLVI New York Giants L 17-21- 02/01/15 XLIX Seattle W 28-24 02/05/17 LI Atlanta W 34-28 (OT) PATRIOTS WILL NOW HAVE A CHANCE TO TIE FOR MOST SUPER BOWL WINS The Patriots will have a chance to tie Pittsburgh for the NFL lead with six Super Bowl wins in franchise history. -

Mountaineers in the Pros

MOUNTAINEERS IN THE PROS Name (Years Lettered at WVU) Team/League Years Stedman BAILEY ALEXANDER, ROBERT (77-78-79-80) Los Angeles Rams (NFL) 1981-83 Los Angeles Express (USFL) 1985 ANDERSON, WILLIAM (43) Boston Yanks (NFL) 1945 ATTY, ALEXANDER (36-37-38) New York Giants (NFL) 1948 AUSTIN, TAVON (2009-10-11-12) St. Louis Rams (NFL) 2013 BAILEY, RUSSELL (15-16-17-19) Akron Pros (APFA) 1920-21 BAILEY, STEDMAN (10-11-12) St. Louis Rams (NFL) 2013 BAISI, ALBERT (37-38-39) Chicago Bears (NFL) 1940-41,46 Philadelphia Eagles (NFL) 1947 BAKER, MIKE (90-91-93) St. Louis Stampede (AFL) 1996 Albany Firebirds (AFL) 1997 Name (Years Lettered at WVU) Name (Years Lettered at WVU) Grand Rapids Rampage (AFL) 1998-2002 Team/League Years Team/League Years BARBER, KANTROY (94-95) BRAXTON, JIM (68-69-70) CAMPBELL, TODD (79-80-81-82) New England Patriots (NFL) 1996 Buffalo Bills (NFL) 1971-78 Arizona Wranglers (USFL) 1983 Carolina Panthers (NFL) 1997 Miami Dolphins (NFL) 1978 Miami Dolphins (NFL) 1998-99 CAPERS, SELVISH (2005-06-07-08) BREWSTER, WALTER (27-28) New York Giants (NFL) 2012 BARCLAY, DON (2008-09-10-11C) Buffalo Bisons (NFL) 1929 Green Bay Packers 2012-13 CARLISS, JOHN (38-39-40) BRIGGS, TOM (91-92) Richmond Rebels (DFL) 1941 BARNUM, PETE (22-23-25-26) Anaheim Piranhas (AFL) 1997 Columbus Tigers (NFL) 1926 CLARKE, HARRY (37-38-39) Portland Forest Dragons (AFL) 1997-99 Chicago Bears (NFL) 1940-43 BARROWS, SCOTT (82-83-84) Oklahoma Wranglers (AFL) 2000-01 San Diego Bombers (PCFL) 1945 Detroit Lions (NFL) 1986-87 Dallas Desperados (AFL) 2002-03 Los -

Opinion of the Supreme Is Irrelevant That the Scheme Has Been L

Monday, January 29, 2001 Page 5B PINION o THE BATTALION Grammy Dreams Eminem’s talent, unique message merit awarding him Album of the Year . mt erce web- ecently, minute it was released. The second cartoonish-like humor. Spin maga 979-280- the Na album, named after his given birth zine named Eminem their Artist of tional name, reflects Eminem’s harsh up the Year, yet another prestigious per Plan R! Academy of bringing, covering issues like accomplishment. Recording Arts & poverty and single parenthood. Quick to defend Eminem’s ' Sciences As seen with his own eyes and Grammy nominations, NARAS wmdstiwc (NARAS) an written by his own hands, Em President C. Michael Greene claims nounced that Em inem’s powerful creation of art the controversy over Eminem’s is, new tu, 0B0, 57S- inem, a 27 year- should not be honored for its mes nomination is no different than the old rapper from Detroit, has been sage or its content, but solely for its actions of comedian Lenny Bruce, nominated for four Grammy awards, artistic and technical achievements. another groundbreaking performer . found offensive by some yet enjoyed lor all insr, including Album of the Year. Although millions of fans Eminem's powerful by many. Greene even called the |j around the world have grown to Eminem recording “remarkable.” H embrace his talent and creativity, creation of art This album should be viewed the , Ldw organizations are vying to keep his should not be way other verbally explicit works g phenomenal album from receiving honored for its are, without questioning the content rtremelyis the award. -

NFL World Championship Game, the Super Bowl Has Grown to Become One of the Largest Sports Spectacles in the United States

/ The Golden Anniversary ofthe Super Bowl: A Legacy 50 Years in the Making An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Chelsea Police Thesis Advisor Mr. Neil Behrman Signed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2016 Expected Date of Graduation May 2016 §pCoJI U ncler.9 rod /he. 51;;:, J_:D ;l.o/80J · Z'7 The Golden Anniversary ofthe Super Bowl: A Legacy 50 Years in the Making ~0/G , PG.5 Abstract Originally known as the AFL-NFL World Championship Game, the Super Bowl has grown to become one of the largest sports spectacles in the United States. Cities across the cotintry compete for the right to host this prestigious event. The reputation of such an occasion has caused an increase in demand and price for tickets, making attendance nearly impossible for the average fan. As a result, the National Football League has implemented free events for local residents and out-of-town visitors. This, along with broadcasting the game, creates an inclusive environment for all fans, leaving a lasting legacy in the world of professional sports. This paper explores the growth of the Super Bowl from a novelty game to one of the country' s most popular professional sporting events. Acknowledgements First, and foremost, I would like to thank my parents for their unending support. Thank you for allowing me to try new things and learn from my mistakes. Most importantly, thank you for believing that I have the ability to achieve anything I desire. Second, I would like to thank my brother for being an incredible role model. -

Page 1 of 3 MINOR LEAGUE FOOTBALL NEWS 8/24/2008 Http

MINOR LEAGUE FOOTBALL NEWS Page 1 of 3 Published Online as a Service to Players, Teams and Leagues Since 1995 Monday, AUG 25, 2008 Summer/Fall Season National Rankings by MLFN NEWS • Front Page · Index of News MINOR LEAGUE FOOTBALL NEWS · This Week's Scores WEEKLY TOP 50 NATIONAL RANKINGS · Arena and Indoor News WINTER/SPRING LEAGUES - 2008 · International Football · All Star Games Rankings for the Weekend Ending July 25, 2008 · The Suess Report · Opinions and Editorials Scores and Standings Data NATIONAL RANKINGS provided by Semi-Pro Football Headquarters · Winter-Spring Rankings (www.semiprofootball.org · Summer-Fall Rankings MLFN EVENTS · Hall of Fame Rank LW Team League G W L T PF PA · MLFN All Star Events · Other National Events SERVICES 1 3 Pacifica Islanders CVFL 13 13 0 0 553 101 · View Events 2 2 South Jersey Generals DFL 10 10 0 0 393 19 · Submit Events 3 1 El Paso Brawlers SWFC 12 11 1 0 545 90 · Submit News or Press Release 4 4 Miami Magic City Bulls FFA 14 14 0 0 459 102 · Submit Scores and 5 5 Edinburg Landsharks TUFL 14 12 2 0 778 103 Results 6 7 Whatcom County Raiders CAFL 9 9 0 0 425 67 USEFUL LINKS 7 12 Iowa Sharks CSFL 8 8 0 0 368 48 · Team/League Logos 8 6 Duval Panthers FFA 12 11 1 0 447 101 CONTACT US 9 8 Bradenton Gladiators FFA 12 11 1 0 426 101 10 9 West Sacramento Wolverines GCFL 12 11 1 0 490 187 11 10 Island Warriors WWFL 11 10 1 0 316 41 Contact Us 12 11 Frederick Outlaws ECFA 13 12 1 0 326 93 NEWS VIA EMAIL 13 13 4 Corners Roughnecks SWFC 13 12 1 0 430 135 14 14 Northern Valley Lions NCAFF 10 8 1 1 339 67 -

Seminoles in the Nfl Draft

137 PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME All-time Florida State gridiron greats Walter Jones and Derrick Brooks are used to making history. The longtime NFL stars added an achievement that will without a doubt move to the top of their accolade-filled biographies when they were inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame inAugust, 2014. Jones and Brooks became the first pair of first-ballot Hall of Famers from the same class who attended the same college in over 40 years. The pair’s journey together started 20 years ago. Just as Brooks was wrapping up his All-America career at Florida State in 1994, Jones was joining the Seminoles out of Holmes Community College (Miss.) for the 1995 season. DERRICK BROOKS Linebacker 1991-94 2014 Pro Football Hall of Fame WALTER JONES Offensive Tackle 1995-96 2014 Pro Football Hall of Fame 138 PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME They never played on the same team at Florida State, but Jones distinctly remembers how excited he was to follow in the footsteps of the star linebacker whom he called the face of the Seminoles’ program. Jones and Brooks were the best at what they did for over a decade in the NFL. Brooks went to 11 Pro Bowls and never missed a game in 14 seasons (all with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers), while Jones became the NFL’s premier left tackle, going to nine Pro Bowls over 12 seasons with the Seattle Seahawks. Both retired in 2008, and, six years later, Jones and Brooks were teammates for the first time as first-ballot Hall of Famers. -

In His First Season As Stanford's Head Coach, Jim

INTRODUCTION SEASON OUTLOOK COACHING STAFF PLAYER PROFILESPLAYER 2007 REVIEW 2008 OPPONENTS RECORDS HISTORY UNIVERSITY In his fi rst season as Stanford’s head coach, Jim Harbaugh led the Cardinal to wins over top-ranked USC and defending Pacifi c-10 Conference co-champion California. WWW.GOSTANFORD.COM • 41 Jim HARBAUGH HEAD COACH Bradford M. Freeman Director of Football Stanford University im Harbaugh, who was appointed the Bradford M. Freeman Director of Football on JDecember 19, 2006, wasted little time in making a big impression in the college football circles in his first season as Stanford’s head coach. Stanford was one of the most improved teams in the Pacific-10 Conference last season under Harbaugh, whose infectious energy and enthusiasm immediately took hold of the program. The Cardinal finished with a 4-8 overall record and a 3-6 mark in conference play last season following a 2006 campaign which saw the team win just one game in 12 outings. Included in last year’s win total was an epic, 24-23 upset win over USC, ranked first in the USA Today Coaches poll and second by the Associated Press at the time, and a convincing win over defending Pac-10 Conference co-champion California, breaking the Bears five-game winning streak in the Big Game. While a pair of signature victories served notice Stanford’s program was again on the rise, Harbaugh is more than ready to push the envelope a little further this season as the Cardinal continue its journey to the upper echelon of a talent-rich conference in its quest to become perennial bowl participants. -

Nfl Super Bowl 48 Patch

Nfl super bowl 48 patch LOOK: Super Bowl XLVIII patches sewn on Broncos, Seahawks uniforms in and enters his seventh season covering the NFL for CBS. Find great deals for Super Bowl Superbowl 48 XLVIII Patch Seattle Seahawks VS Denver Broncos. Shop with Best Selling in Football-NFL. Trending price is. SUPER BOWL XLVIII SUPERBOWL SB 48 CHAMPION Seahawks rout Broncos SUPER BOWL 48 PATCH SEATTLE SEAHAWKS DENVER BRONCOS .. Seahawks Super Bowl NFL Sweatshirts,; Denver Broncos Patch Super Bowl NFL. Product Description. Official NFL Patch & Statistics Card produced by Willabee & Ward in Shop New Era Seattle Seahawks Super Bowl XLVIII On- Field Side Patch 59FIFTY Browse for the latest NFL gear, apparel, collectibles, and. Seattle Seahawks " x " Super Bowl XLVIII Champions Celebration .. Fanatics Authentic Super Bowl On The Fifty Framed 16" x 20" Patches Collage -. Find a Denver Broncos Peyton Manning Nike NFL Super Bowl XLVIII Patch Game Jersey at today! With our huge selection of Denver Broncos Nike. Find a Seattle Seahawks New Era NFL Super Bowl XLVIII On Field Patch 59FIFTY Cap at today! With our huge selection of Seattle Seahawks New Era. If you are a fan of uniform news, then today was your lucky day in the NFL. Earlier on Tuesday, we learned that the Denver Broncos would be. Order a NFL Russell Wilson Seattle Seahawks Elite Alternate Super Bowl XLVIII C Patch Nike Jersey - Grey at official Seahawks Store Today and Enjoy Fast. 1, @, 8/13, W, Does the NFL actually release super bowl patches? . Am looking for a good patch, since can't find a Thomas jersey. -

American Football

COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – SPORTS 0 7830294949 American Football American Football popularly known as the Rugby Football or Gridiron originated in United States resembling a union of Rugby and soccer; played in between two teams with each team of eleven players. American football gained fame as the people wanted to detach themselves from the English influence. The father of this sport Walter Camp altered the shape and size of the ball to an oval-shaped ball called ovoid ball and drawn up some unique set of rules. Objective American Football is played on a four sided ground with goalposts at each end. The two opposing teams are named as the Offense and the Defense, The offensive team with control of the ovoid ball, tries to go ahead down the field by running and passing the ball, while the defensive team without control of the ball, targets to stop the offensive team’s advance and tries to take control of the ball for themselves. The main objective of the sport is scoring maximum number of goals by moving forward with the ball into the opposite team's end line for a touchdown or kicking the ball through the challenger's goalposts which is counted as a goal and the team gets points for the goal. The team with the most points at the end of a game wins. THANKS FOR READING – VISIT OUR WEBSITE www.educatererindia.com COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – SPORTS 0 7830294949 Team Size American football is played in between two teams and each team consists of eleven players on the field and four players as substitutes with total of fifteen players in each team. -

Super Bowl Sunday: an Unofficial Holiday for Millions

Embassy of the United States of America Super Bowl Sunday An Unofficial Holiday for Millions Seattle Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson holds the Lombardi Trophy after the 2014 Super Bowl game. The Seahawks will again vie for the championship in 2015 against the New England Patriots. © AP Images ach year, on a Sunday at the this is because the Super Bowl is a single game each year between end of January or beginning a single game, a winner-take-all their respective champion teams. Eof February, tens of millions contest. Add the televised enter- Because many collegiate football of Americans declare their own tainment that surrounds the game, championships were known as unofficial holiday. Gathered in and Super Bowl Sunday becomes “bowls” for the bowl-shaped sta groups large and small, nearly half an event even for those who are not diums that hosted them, one AFL of all U.S. households participate football fans. owner referred to the new game as vicariously in a televised spectacle a “super” bowl. The name stuck. that has far outgrown its origins as Super Bowl Beginnings Four Super Bowl games were a sporting event. American football is unrelated played before the two leagues The Super Bowl, which deter- to the game most of the world knows merged in 1970 into a single mines the championship of by that name, which Americans National Football League, which American football, is most of all a call soccer. For most of its history, was subdivided into the American shared experience, when Americans professional American football was and National “conferences.” Each choose to watch the game with played within a single National year, the champion teams of each friends.