Digital Divide”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girl Scouts of Central Texas Explore Austin Patch Program

Girl Scouts of Central Texas Explore Austin Patch Program Created by the Cadette and Senior Girl Scout attendees of Zilker Day Camp 2003, Session 4. This patch program is a great program to be completed in conjunction with the new Capital Metro Patch Program available at gsctx.org/badges. PATCHES ARE AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE IN GSCTX SHOPS. Program Grade Level Requirements: • Daisy - Ambassador: explore a minimum of eight (8) places. Email [email protected] if you find any hidden gems that should be on this list and share your adventures here: gsctx.org/share EXPLORE 1. Austin Nature and Science Center, 2389 Stratford Dr., (512) 974-3888 2. *The Contemporary Austin – Laguna Gloria, 700 Congress Ave. (512) 453-5312 3. Austin City Limits – KLRU at 26th and Guadalupe 4. *Barton Springs Pool (512) 867-3080 5. BATS – Under Congress Street Bridge, at dusk from March through October. 6. *Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, 1800 Congress Ave. (512) 936-8746 7. Texas State Cemetery, 909 Navasota St. (512) 463-0605 8. *Deep Eddy Pool, 401 Deep Eddy. (512) 472-8546 9. Dinosaur Tracks at Zilker Botanical Gardens, 2220 Barton Springs Dr. (512) 477-8672 10. Elisabet Ney Museum, 304 E. 44th St. (512) 974-1625 11. *French Legation Museum, 802 San Marcos St. (512) 472-8180 12. Governor’s Mansion, 1010 Colorado St. (512) 463-5518 13. *Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, 4801 La Crosse Ave. (512) 232-0100 14. LBJ Library 15. UT Campus 16. Mayfield Park, 3505 W. 35th St. (512) 974-6797 17. Moonlight Tower, W. 9th St. -

1996-2015 Texas Book Festival Library Award Winners

1996-2015 Texas Book Festival Library Award Winners Abernathy Arlington Public Library, East Riverside Drive Branch Abernathy Public Library - 2000 Arlington Branch - 1996, 1997, Austin Public Library - 2004, 2007 Abilene 2001, 2008, 2014, 2015 Daniel H. Ruiz Branch Abilene Public Library – 1998, Arlington Public Library - 1997 Austin Public Library - 2001, 2006, 2009 Northeast Branch 2011 Abliene Public Library, South Arlington Public Library Southeast SE Austin Community Branch Branch - 1999 Branch Library - 2015 Austin Public Library - 2004 Alamo Arlington Public Library, Spicewood Springs Branch Lalo Arcaute Public Library - 2001 Woodland West Branch-2013 Albany George W. Hawkes Central Austin Public Library- 2009 Shackelford Co. Library - 1999, Library, Southwest Branch - St. John Branch Library 2004 2000, 2005, 2008, 2009 Austin Public Library - 1998, 2007 Alice Aspermont Terrazas Branch Alice Public Library - 2003 Stonewall Co. Public Library - Austin Public Library - 2007 Allen 1997 University Hills Branch Library Allen Public Library - 1996, 1997 Athens Austin Public Library - 2005 Alpine Henderson Co. Clint W. Murchison Windsor Park Branch Alpine Public Library – 1998, Memorial Library - 2000 Austin Public Library - 1999 2008, 2014 Aubrey Woodland West Branch Alpine Public Library South Aubrey Area Library - 1999 Cepeda Public Library - 2000, Branch - 2015 Austin 2006 Alto Austin Public Library - 1996, 2004 Lake Travis High - 1997 Stella Hill Memorial Library - Austin Public Library - 2004, 2007 School/Community Library 1998, -

Beck's Risk Society and Giddens' Search for Ontological Security: a Comparative Analysis Between the Anthroposophical Society and the Assemblies of God

Volume 15, Number 1 27 Beck's Risk Society and Giddens' Search for Ontological Security: A Comparative Analysis Between the Anthroposophical Society and the Assemblies of God Alphia Possamai-Inesedy University of Western Sydney There is a contention by social theorists such as Beck, Giddens, Bauman and Lash that contemporary Western society is in a transitional period in which risks have proliferated as an outcome of modernisation. In accordance with these changes individuals' sense ofselfhood have moved toward being more sensitive as to what they define as risks, such as threats to their health, as economic security or emotional wellbeing than they were in previous eras. Living in such a world can lead individuals to what Giddens would term ontological insecurity. Obsessive exaggeration of risks to personal existence, extreme introspection and moral vacuity are characteristics of the ontologically insecure individual. The opposite condition, ontological security, when achieved, leaves the individual with a sense of continuity and stability, which enables him or her to cope effectively with risk situations, personal tensions and anxiety. This emergent field of study in sociology has nevertheless poorly addressed religious issues; as if these social researchers have omitted parts of the religious aspects ofcontemporary society. This article attempts to fill this lacuna and explores the notion of risk society and ontological security with that of postmodern religion/spiritualities. Two case studies of the Anthroposophical society and Pentecostalism aid in this task. UlrichBeck(1992; 1994; 1995; 1996)andAnthonyGiddens(1990; 1991; 1994; 1999) while differing in their approaches, share similar concerns, foci and epistemological underpinnings in their work. -

LETTER to G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS

LETTER TO G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS We write to call for urgent action to address the global education emergency triggered by Covid-19. With over 1 billion children still out of school because of the lockdown, there is now a real and present danger that the public health crisis will create a COVID generation who lose out on schooling and whose opportunities are permanently damaged. While the more fortunate have had access to alternatives, the world’s poorest children have been locked out of learning, denied internet access, and with the loss of free school meals - once a lifeline for 300 million boys and girls – hunger has grown. An immediate concern, as we bring the lockdown to an end, is the fate of an estimated 30 million children who according to UNESCO may never return to school. For these, the world’s least advantaged children, education is often the only escape from poverty - a route that is in danger of closing. Many of these children are adolescent girls for whom being in school is the best defence against forced marriage and the best hope for a life of expanded opportunity. Many more are young children who risk being forced into exploitative and dangerous labour. And because education is linked to progress in virtually every area of human development – from child survival to maternal health, gender equality, job creation and inclusive economic growth – the education emergency will undermine the prospects for achieving all our 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and potentially set back progress on gender equity by years. -

African American Resource Guide

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE Sources of Information Relating to African Americans in Austin and Travis County Austin History Center Austin Public Library Originally Archived by Karen Riles Austin History Center Neighborhood Liaison 2016-2018 Archived by: LaToya Devezin, C.A. African American Community Archivist 2018-2020 Archived by: kYmberly Keeton, M.L.S., C.A., 2018-2020 African American Community Archivist & Librarian Shukri Shukri Bana, Graduate Student Fellow Masters in Women and Gender Studies at UT Austin Ashley Charles, Undergraduate Student Fellow Black Studies Department, University of Texas at Austin The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use. INTRODUCTION The collections of the Austin History Center contain valuable materials about Austin’s African American communities, although there is much that remains to be documented. The materials in this bibliography are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This bibliography is one in a series of updates of the original 1979 bibliography. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals and support groups. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the online computer catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing collection holdings by author, title, and subject. These entries, although indexing ended in the 1990s, lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be time-consuming to find and could be easily overlooked. -

Factor Endowment Versus Productivity Views

Globalization, Poverty, and All That: Factor Endowment versus Productivity Views William Easterly New York University Prepared for NBER Globalization and Poverty Workshop, September 10-12, 2004 Globalization causing poverty is a staple of anti-globalization rhetoric. The Nobel prizewinner Dario Fo compared the impoverishment of globalization to September 11th: "The great speculators wallow in an economy that every year kills tens of millions of people with poverty—so what is 20,000 dead in New York?” 1 The protesters usually believe globalization is a disaster for the workers, throwing them into “downward wage spirals in both the North and the South.” Oxfam identifies such innocuous products as Olympic sportswear as forcing laborers into “working ever-faster for ever-longer periods of time under arduous conditions for poverty-level wages, to produce more goods and more profit.”2 According to a best-selling book by William Greider, in the primitive legal climate of poorer nations, industry has found it can revive the worst forms of nineteenth century exploitation, abuses outlawed long ago in the advanced economies, including extreme physical dangers to workers and the use of children as expendable cheap labor.3 Oxfam complains about how corporate greed is “exploiting the circumstances of vulnerable people,” which it identifies mainly as young women, to set up profitable “global supply chains” for huge retailers like Walmart. In China’s fast-growing Guandong Province, “young women face 150 hours of overtime each month in the garment factories -

Muffled Voices of the Past: History, Mental Health, and HIPAA

INTERSECT: PERSPECTIVES IN TEXAS PUBLIC HISTORY 27 Muffled Voices of the Past: History, Mental Health, and HIPAA by Todd Richardson As I set out to write this article, I wanted to explore mental health and the devastating toll that mental illness can take on families and communities. Born out of my own personal experiences with my family, I set out to find historical examples of other people who also struggled to find treatment for themselves or for their loved ones. I know that when a family member receives a diagnosis of a chronic mental illness, their life changes drastically. Mental illness affects individuals and their loved ones in a variety of ways and is a grueling experience for all parties involved. When a family member’s mind crumbles, often that person— the brother or father or favorite aunt— is gone forever. Families, left helpless, watch while a person they care for exists in a state of constant anguish. I understood that my experiences were neither new nor unique. As a student of history, I knew that other families’ stories must exist somewhere in the recorded past. By looking back through time, I hoped to shine a light on the history of American mental health policy and perhaps to make the voices of those affected by mental illness heard. Doing so might bring some sense of justice and awareness to the lives of people with mental illness in the present in the same way that history allows other marginalized groups to make their voices heard and reshape the way people perceive the past. -

2019-20 MALA Members and Partners * Libraries Noted As MOBIUS* Are

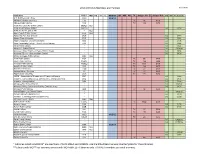

2019-20 MALA Members and Partners 10/2/2019 Institution OCLC MO KS IA IL MOBIUS AR NM OK TX Amigos Site ID Amigos Hub CO WY CLiC Code A.T. Still Memorial Library WG1 MOBIUS Abilene Christian University TXC TX 36 WTX Abilene Public Library TXB TX 155 WTX Academie Lafayette School Library MOALC MO Academy 20 School District COPCH CO C314 Academy for Integrated Arts * MO Adair County Public Library KVA MO Adams 12 Five Star Schools DVA CO C878 Adams State University CLZ CO C384 Adams-Arapahoe 28J School District XN0 CO C108 Aims Community College - Jerry A. Kiefer Library CAA CO C884 Akron Public Library * CO C824 Akron R-1 School District * CO C824.as Alamosa Library (Southern Peaks Public Library) * CO C404 Alamosa RE-11J - Alamosa High School * CO C406 Albany Carnegie Public Library MQ2 MO Allen Public Library TOP TX 95 DFW Alpine Public Library TXAPL TX 122 HKB Alvarado Public Library TXADO TX 8801 DFW Amarillo Public Library TAP TX 156 WTX Amberton University TAM TX 27 DFW Amigos Library Services IIC TX 23 DFW Angelo State University ANG TX 19 WTX AORN - Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses DNF CO C886 Arapahoe Community College Library and Learning Commons DVZ CO C874 Arapahoe Library District CO2 CO C214 Arickaree R-2 School District * CO C840.ar Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility General Library * CO C402 Arlington Public Library AR9 TX 98 DFW Arriba-Flagler C-20 School District * CO C836.af Arrowhead Correctional Center * CO C370 Assistive Technology Partners (SWAAAC) * CO C209 Atchison County Library MQ3 MO Aubrey -

Mexican American Resource Guide: Sources of Information Relating to the Mexican American Community in Austin and Travis County

MEXICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE: SOURCES OF INFORMATION RELATING TO THE MEXICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY IN AUSTIN AND TRAVIS COUNTY THE AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER, AUSTIN PUBLIC LIBRARY Updated by Amanda Jasso Mexican American Community Archivist September 2017 Austin History Center- Mexican American Resource Guide – September 2017 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use so that customers can learn from the community’s collective memory. The collections of the AHC contain valuable materials about Austin and Travis County’s Mexican American communities. The materials in the resource guide are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This guide is one of a series of updates to the original 1977 version compiled by Austin History staff. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals, support groups and Austin History Center staff. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the Find It: Austin Public Library On-Line Library Catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing individual items in the collection with entries under author, title, and subject. These tools lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be very difficult to find. It must be noted that there are still significant gaps remaining in our collection in regards to the Mexican American community. -

The Consequences of Modernity Anthony Giddens

The Consequences of Modernity Anthony Giddens POLITY PRESS Introduction In what follows I shall develop an institutional analysis of modernity with cultural and epistemological over- tones. In so doing, I differ substantially from most current discussions, in which these emphases are reversed. What is modernity? As a first approximation, let us simply say the following: "modernity" refers to modes of social life or organisation which emerged in Europe from about the seventeenth century onwards and which subsequently be- came more or less worldwide in their influence. This as- sociates modernity with a time period and with an initial geographical location, but for the moment leaves its ma- jor characteristics safely stowed away in a black box. Today, in the late twentieth century, it is argued by many, we stand at the opening of a new era, to which the social sciences must respond and which is taking us be- yond modernity itself. A dazzling variety of terms has been suggested to refer to this transition, a few of which refer positively to the emergence of a new type of social system (such as the "information society" or the "con- sumer society") but most of which suggest rather that a preceding state of affairs is drawing to a close ("post- outside of our control. To analyse how this has come to modernity," "post-modernism," "post-industrial soci- be the case, it is not sufficient merely to invent new terms, ety," "post-capitalism," and so forth). Some of the de- like post-modernity and the rest. Instead, we have to look bates about these matters concentrate mainly upon insti- again at the nature of modernity itself which, for certain tutional transformations, particularly those which pro- fairly specific reasons, has been poorly grasped in the so- pose that we are moving from a system based upon the cial sciences hitherto. -

How Did Texas Grow One City at a Time? Case Study: Austin

Instructional Recipe How Did Texas Grow One City at a Time? Online research and information resources available through a partnership between Case Study: Austin the Texas State Library and Archives Grade 7, Texas History Commission, the Texas Education Agency and Education Service Center, Region 20 http://web.esc20.net/k12databases TEKS: Step 1 – Ask (7.8 B) analyze and interpret geographic distributions and patterns in Texas during the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. Objectives: (7.9 A) locate the Mountains and Basins, Students will analyze the impact of geographic, political, social Great Plains, North Central Plains, and and economic factors that contributed to the growth of Austin, Coastal Plains regions and places of th th Texas. importance in Texas during the 19 , 20 , and 21st centuries such as major cities, rivers, natural and historic landmarks, Introduction: political and cultural regions, and local points of interest. (7.12 A) explain economic factors that led to the urbanization of Texas. (7.21 A) differentiate between, locate, and use primary and secondary sources such as computer software, databases, media and news services, biographies, interviews, and artifacts to acquire information about Texas. (7.21B) analyze information by sequencing, categorizing, identifying cause-and-effect relationships, comparing, contrasting, finding the main idea, summarizing, making generalizations and predictions, and drawing inferences and conclusions. (7.21C) organize and interpret information from outlines, reports, databases, and visuals including graphs, charts, timelines, and maps. (7.21D) identify points of view from the historical context surrounding an event and Bird’s Eye View of Austin, Texas, before 1910. Prints and the frame of reference that influenced the Photographs Collection, Texas State Library and Archives. -

Minority Group Theory

2 Theories of Poverty In the social sciences it is usual to start with conceptions or definitions of a social problem or phenomenon and proceed first to its measurement and then its ex- planation before considering, or leaving others to consider, alternative remedies. The operation of value assumptions at each stage tends to be overlooked and the possibility that there might be interaction between, or a conjunction of, these stages tends to be neglected. What has to be remembered is that policy prescriptions permeate conceptualization, measurement and the formulation of theory; alternatively, that the formulation of theory inheres within the conceptualization and measurement of a problem and the application of policy. While implying a particular approach to theory, Chapter 1 was primarily con- cerned with the conceptualization and measurement of poverty in previous studies. This chapter attempts to provide a corresponding account of previous theories of poverty. It will discuss minority group theory, the sub-culture of poverty and the cycle of deprivation, orthodox economic theory, dual labour market and radical theories, and sociological, including functionalist, explanations of poverty and inequality. Until recently, little attempt was made to extend theory to the forms, extent of and changes in poverty as such. Social scientists, including Marx, had been primarily concerned with the evolution of economic, political and social inequality. Economists had devoted most interest to the factor shares of production and distribution rather than to the unequal distribution of resources, and where they had studied the latter, they confined themselves to studies of wages. Sociologists had kept the discussion of the origins of, or need for, equality at a very general level, or had confined their work to topics which were only indirectly or partly related, like occupational status and mobility, and the structure and persistence of local community.