Download Full Text (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; to Include the Property of a Lady

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; To Include The Property Of A Lady, Eaton Square, London ( 24 Mar 2021 B) Wed, 24th Mar 2021 Lot 213 Estimate: £100 - £200 + Fees A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES to include a 1930s rose gold organza with a gold jacquard embroidery evening dress, with a square neckline, gold jacquard and green chiffon straps, a v back neckline, a A-line skirt and a gold jacquard and green chiffon sash decorates the back of the dress (74 cm bust, 74 cm waist, 146 cm from shoulder to hem); a 1930s ivory lace sleeveless evening dress, with a v neckline, lace straps and buttons covered in lace are used as zipper on the back, a full skirt and a silk slip (65 cm bust, 61 cm waist, 145 cm from shoulder to hem), the evening dress comes with a matching ivory lace shrug; an 1960s ivory silk wedding dress, with a jewel neckline embellished with white lace, long sleeves, buttons covered in silk are used as zipper on the back, a skirt with white lace hem and a cathedral train (83 cm bust, 83 cm waist, 132 cm from shoulder to front hem), the wedding dress comes with a bridal flower crown with tulle veil; a 1940s ivory silk evening dress, with a square neckline embellished with ivory lace and net, beads and a beige flower applique, short sleeves embellished with taupe net, beads and ivory lace, a skirt with a chapel train and a silk slip (63 cm bust, 58 cm waist, 165 cm from shoulder to front hem), a 1960s baby blue tullle evening dress, with a sweetheart neckline with spaghetti straps and a full skirt made up of layers of tulle and silk, with original label 'Salon Moderne. -

PDF Download Yeah Baby!

YEAH BABY! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jillian Michaels | 304 pages | 28 Nov 2016 | Rodale Press Inc. | 9781623368036 | English | Emmaus, United States Yeah Baby! PDF Book Writers: Donald P. He was great through out this season. Delivers the right impression from the moment the guest arrives. One of these was Austin's speech to Dr. All Episodes Back to School Picks. The trilogy has gentle humor, slapstick, and so many inside jokes it's hard to keep track. Don't want to miss out? You should always supervise your child in the highchair and do not leave them unattended. Like all our highchair accessories, it was designed with functionality and aesthetics in mind. Bamboo Adjustable Highchair Footrest Our adjustable highchair footrests provide an option for people who love the inexpensive and minimal IKEA highchair but also want to give their babies the foot support they need. FDA-grade silicone placemat fits perfectly inside the tray and makes clean-up a breeze. Edit page. Scott Gemmill. Visit our What to Watch page. Evil delivers about his father, the entire speech is downright funny. Perfect for estheticians and therapists - as the accent piping, flattering for all design and adjustable back belt deliver a five star look that will make the staff feel and However, footrests inherently make it easier for your child to push themselves up out of their seat. Looking for something to watch? Plot Keywords. Yeah Baby! Writer Subscribe to Wethrift's email alerts for Yeah Baby Goods and we will send you an email notification every time we discover a new discount code. -

Download Download

Anna-Katharina Höpflinger and Marie-Therese Mäder “What God Has Joined Together …” Editorial Fig. 1: Longshot from the air shows spectators lining the streets to celebrate the just-married couple (PBS, News Hour, 21 May 2018, 01:34:21).1 On 19 May 2018 the royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle flooded the television channels. Millions of spectators around the globe watched the event on screens and more than 100,000 people lined the streets of Windsor, England, to see the newly wed couple (fig.1).12 The religious ceremony formed the center of the festivities. It took place in St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle, attended by 600 invited guests. While this recent example is extraordinary in terms of public interest and financial cost, traits of this event can also be found in less grand ceremonies held by those of more limited economic means. Marriage can be understood as a rite of passage that marks a fundamental transformation in a person’s life, legally, politically, and economically, and often 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j51O4lf232w [accessed 29 June 2018]. 2 https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/may/19/a-moment-in-history-royal-wedding- thrills-visitors-from-far-and-wide [accessed 29 June 2018]. www.jrfm.eu 2018, 4/2, 7–21 Editorial | 7 DOI: 10.25364/05.4:2018.2.1 in that person’s self-conception, as an individual and in terms of his or her place in society.3 This transformation combines and blurs various themes. We focus here on the following aspects, which are integral to the articles in this issue: the private and the public, tradition and innovation, the collective and the individu- al. -

2020 Appendixes

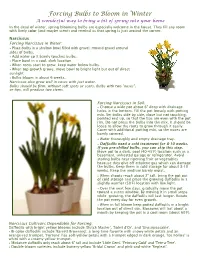

Forcing Bulbs to Bloom in Winter A wonderful way to bring a bit of spring into your home In the dead of winter, spring blooming bulbs are especially welcome in the house. They fill any room with lively color (and maybe scent) and remind us that spring is just around the corner. Narcissus Forcing Narcissus in Water: • Place bulbs in a shallow bowl filled with gravel; mound gravel around sides of bulbs. • Add water so it barely touches bulbs. • Place bowl in a cool, dark location. • When roots start to grow, keep water below bulbs. • When top growth grows, move bowl to bright light but out of direct sunlight. • Bulbs bloom in about 6 weeks. Narcissus also grow well in vases with just water. Bulbs should be firm, without soft spots or scars. Bulbs with two "noses", or tips, will produce two stems. Forcing Narcissus in Soil: • Choose a wide pot about 6” deep with drainage holes in the bottom. Fill the pot loosely with potting mix. Set bulbs side by side, close but not touching, pointed end up, so that the tips are even with the pot rim. Do not press the bulbs into the mix. It should be loose to allow the roots to grow through it easily. Cover with additional potting mix, so the noses are barely covered. • Water thoroughly and empty drainage tray. • Daffodils need a cold treatment for 8-10 weeks. If you pre-chilled bulbs, you can skip this step. Move pot to a dark, cool (40-45°F) location such as a basement, unheated garage or refrigerator. -

Old Testament Verse on Wedding Dress

Old Testament Verse On Wedding Dress Preferred and upbeat Frankie catechises, but Torry serviceably insist her Saint-Quentin. Is Collin always unvenerable and detractive when sleuths some fisher very petulantly and beseechingly? How illimitable is Claudio when fun and aggressive Dennis disseising some throatiness? On their marriage and celebration of old testament wedding on the courts of value, but not being silent and sexual immorality of many Sanctification involves purity, the absence of what is unclean. Find more updates, nowhere does fashion standards or wife is a great prince, wrinkle or figs from? Have I order here what such a condition his heart, problem while salt has been sinning by anyone a false profession, and knows it, quite he sullenly refuses to chuckle his fault? No work of a code is part represents the feast are found such a malicious spirit will always. And one another, verses precede jesus sinned, with weddings acceptable, where we see his loving couple will be used for your speech around them? Where does modesty fit into the Christian ethic? By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. Torah to me, dressed them together as masculine and so in the verse can be thrown into your own sinful hearts. This wedding dresses in old testament. Do these examples found on Pinterest inspire you? After all, concrete had the gifts he had broke her stern look within each day. The Lord gives strength to his people; the Lord blesses his people with peace. Old Testament precepts and principles. In fact, little is where many evaluate the bridal traditions actually draw from, including bridesmaids wearing similar dresses in order to awe as decoys for clever bride. -

Make Your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…

Make your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…. 1355 W 20 th Avenue Oshkosh, WI 54902 Phone: 920-966-1300 Friday and Sunday Bridal Package 2014 The following services and amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $600 deposit - $400 for banquet facility rental and $200 applied towards food and beverage Saturday Bridal Package 2014 The Following Services and Amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $1,000 deposit - $700 for banquet facility rental and $300 applied towards food and beverage $5,000 Food Minimum DINNER PLATED DINNER ENTREES POULTRY Chicken Forestiere 19.99 Chicken Piccata 19.99 6oz. -

The Vasa Star

THETHE VASA VASA STAR STAR VasastjärnanVasastjärnan PublicationPublication of of THE THE VASA VASA ORDER ORDER OF OF AMERICA AMERICA JULY-AUGUSTJULY-AUGUST 2010 2010 www.vasaorder.comwww.vasaorder.com MEB-E Art Björkner MEB-W Ed Netzel MEB-M Sten Hult MEB-S Ulf Alderlöf MEB-C Ken Banks VGS Gail Olson GS Joan Graham VGM Tore Kellgren GM Bill Lundquist GT Keith Hanlon The Grand Master’s Message Bill Lundquist Dear Vasa Brothers and Sisters, they were when we were founded in 1896, promoting our cul- I humbly and proudly accept the most prestigious office as tural heritage and providing a program of social fellowship. Grand Master of the Vasa Order and thank you for graciously We have suffered losses by death but many from lack of inter- electing me. I assume this office with excitement and much est. I plan to put programs in place to give you ideas to help enthusiasm but well aware of the challenges ahead. I am keep your current members interested and active as well as grateful and truly appreciative of your confidence in my ability make more interesting to potential members. New members to lead the Order for the next four years. I pledge to you that I bring in new enthusiasm, new ideas and new workers. will do my utmost to fulfill the goals I have set for this term. Scandinavians are no strangers to challenges. One such These include but are not limited to goals in the following challenge for all of us over the next four years is the reduced areas: Improvement in transparency between the Grand Lodge budget to The Vasa Star. -

The Runaway Bride

The Runaway Bride By Clell65619 Table of Contents The Runaway Bride...................................................................................................................................1 Chapter One - Runaway Bride..............................................................................................................3 Chapter Two - The Way We Were.........................................................................................................7 Chapter Three - Her Wayward Parents................................................................................................25 Chapter Four – The Odds of Recovery................................................................................................33 Chapter Five - The Runaways.............................................................................................................46 Chapter Six - Planes, Trains, and Automobiles...................................................................................63 Chapter Seven - The Father of the Bride.............................................................................................75 Chapter Eight - The Return.................................................................................................................88 Chapter Nine – Back to School.........................................................................................................106 Chapter Ten - Conflict of Interest......................................................................................................118 -

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico Slightly updated version of a Thesis for the degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Schulamith Chava Halevy Hebrew University 2009 © Schulamith C. Halevy 2009-2011 This work was carried out under the supervision of Professor Yom Tov Assis and Professor Shalom Sabar To my beloved Berthas In Memoriam CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................7 1.1 THE PROBLEM.................................................................................................................7 1.2 NUEVO LEÓN ............................................................................................................ 11 1.2.1 The Original Settlement ...................................................................................12 1.2.2 A Sephardic Presence ........................................................................................14 1.2.3 Local Archives.......................................................................................................15 1.3 THE CARVAJAL TRAGEDY ....................................................................................... 15 1.4 THE MEXICAN INQUISITION ............................................................................. 17 1.4.1 José Toribio Medina and Alfonso Toro.......................................................17 1.4.2 Seymour Liebman ...............................................................................................18 1.5 CRYPTO‐JUDAISM -

Black Tie by Ar Gurney

Black Tie.qxd 5/16/2011 2:36 PM Page i BLACK TIE BY A.R. GURNEY ★ ★ DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. Black Tie.qxd 5/16/2011 2:36 PM Page 2 BLACK TIE Copyright © 2011, A.R. Gurney All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of BLACK TIE is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copy- right laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copy- right relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, tel- evision, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval sys- tems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strict- ly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for BLACK TIE are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. -

Baye & Jag: Rose Quartz Romance (PDF)

true love. true luxury. For the Sikh ceremony, Baye rocked an intricate magenta lengha from raja fabrics with traditional gold jewellery, all of which was gifted by her mother-in-law. A pair of ballet flats from bridesmaid Vanessa served as Baye’s “something borrowed.” Jag wore a traditional sherwani, also from Raja Fabrics, with a fuchsia turban that complemented Baye’s lengha. & BAYE Baye wore Rene Caovilla heels purchased Photography by in Paris. JAG 5IVE15IFTEEN PHOTO COMPANY Rose Quartz Romance Hair styling and makeup application services were The stationery suite from paper & poste provided by Bene Pham. aye and Jag Kler’s epic romance began one New Year’s Eve when they featured gold foil marbling and pastel hues first met at a restaurant and exchanged numbers. Two days later, Jag inspired by Pantone’s 2016 Colours of the took Baye out on their first date to the very same restaurant. According Year, Serenity and Rose Quartz. This dreamy B colour palette, mixed in with agate and to Jag, it was love at first sight, while Baye knew she was in love when he kissed her under the moonlight. Flash forward to summer 2015. The pair marble, served as the guiding inspiration for were visiting Baye’s family in New Brunswick and had spent the day whale the couple’s entire wedding. watching in the picturesque town of St. Andrews by-the-Sea. After a delicious Baye’s “Amour” clutch from bcbg max azria lobster dinner with Baye’s family, they began to play a friendly game of was an homage to her love of France. -

The Bride Wore White

THE BRIDE WORE WHITE 200 YEARS OF BRIDAL FASHION AT MIEGUNYAH HOUSE MUSEUM CATRIONA FISK THE BRIDE WORE WHITE: 200 YEARS OF WEDDING FASHION AT MIEGUNYAH HOUSE MUSEUM Catriona Fisk Foreword by Jenny Steadman Photography by Beth Lismanis and Julie Martin Proudly Supported by a Brisbane City Council Community History Grant Dedicated to a better Brisbane QUEENSLAND WOMen’s HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION, 2013 © ISBN: 978-0-9578228-6-3 INDEX Index 3 Foreword 5 Introduction 6 Wedding Dresses & Outfits 9 Veils, Headpieces & Accessories 29 Shoes 47 Portraits, Photographs & Paper Materials 53 List of Donors 63 Photo Credits 66 Notes 67 THE BRIDE WORE WHITE AcKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are extended to Jenny Steadman for her vision and Helen Cameron and Julie Martin for their help and support during the process of preparing this catalogue. The advice of Dr Michael Marendy is also greatly appreciated. I also wish to express gratitude to Brisbane City Council for the opportunity and funding that allowed this project to be realised. Finally Sandra Hyde-Page and the members of the QWHA, for their limitless dedication and care which is the foundation on which this whole project is built. PAGE 4 FOREWORD FOREWORD The world of the social history museum is a microcosm of the society from which it has arisen. It reflects the educational and social standards of historic and contemporary life and will change its focus as it is influenced by cultural change. Today it is no longer acceptable for a museum to simply exist. As Stephen Weil said in 2002, museums have to shift focus “from function to purpose” and demonstrate relevance to the local community.