Metaphysics – Transcendence – Atheism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 13, 2009 (XVIII:1) Carl Theodor Dreyer VAMPYR—DER TRAUM DES ALLAN GREY (1932, 75 Min)

January 13, 2009 (XVIII:1) Carl Theodor Dreyer VAMPYR—DER TRAUM DES ALLAN GREY (1932, 75 min) Directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer Produced by Carl Theodor Dreyer and Julian West Cinematography by Rudolph Maté and Louis Née Original music by Wolfgang Zeller Film editing by Tonka Taldy Art direction by Hermann Warm Special effects by Henri Armand Allan Grey…Julian West Der Schlossherr (Lord of the Manor)…Maurice Schutz Gisèle…Rena Mandel Léone…Sybille Schmitz Village Doctor…Jan Heironimko The Woman from the Cemetery…Henriette Gérard Old Servant…Albert Bras Foreign Correspondent (1940). Some of the other films he shot His Wife….N. Barbanini were The Lady from Shanghai (1947), It Had to Be You (1947), Down to Earth (1947), Gilda (1946), They Got Me Covered CARL THEODOR DREYER (February 3, 1889, Copenhagen, (1943), To Be or Not to Be (1942), It Started with Eve (1941), Denmark—March 20, 1968, Copenhagen, Denmark) has 23 Love Affair (1939), The Adventures of Marco Polo (1938), Stella Directing credits, among them Gertrud (1964), Ordet/The Word Dallas (1937), Come and Get It (1936), Dodsworth (1936), A (1955), Et Slot i et slot/The Castle Within the Castle (1955), Message to Garcia (1936), Charlie Chan's Secret (1936), Storstrømsbroen/The Storstrom Bridge (1950), Thorvaldsen Metropolitan (1935), Dressed to Thrill (1935), Dante's Inferno (1949), De nåede færgen/They Caught the Ferry (1948), (1935), Le Dernier milliardaire/The Last Billionaire/The Last Landsbykirken/The Danish Church (1947), Kampen mod Millionaire (1934), Liliom (1934), Paprika (1933), -

2. the Slow Pulse of the Era: Carl Th. Dreyer's Film Style

2. THE SLOW PULSE OF THE ERA: CARL TH. DREYER’S FILM STYLE C. Claire Thomson Introduction The very last shot of Carl Th. Dreyer’s very last film, Gertrud (1964), devotes forty-five seconds to the contemplation of a panelled door behind which the eponymous heroine has retreated with a wave to her erstwhile lover. The camera creeps backwards to establish Dreyer’s valedictory tableau on which it lingers, immobile, for almost thirty seconds: the door and a small wooden stool beside it. The composition is of such inert, grey geometry that, in its closing moments, this film resembles nothing so much as a Vilhelm Hammershøi painting, investing empty domestic space with the presences that have passed through its doors and hallways. If, in this shot, the cinematic image fleetingly achieves the condition of painting, it is the culmination of a directorial career predicated on the productive tension between movement and stillness, sound and silence, rhythm and slowness. At the end of Gertrud, where the image itself slows into calm equilibrium, we witness the end point of an entropic career. As Dreyer’s film style slowed, so, too, did his rate of production. The intervals between his last four major films – the productions that write Dreyer into slow cinema’s prehistory – are measured in decades, not years: Vampyr (1932), Vredens Dag (Day of Wrath, 1943), Ordet (The Word, 1955), Gertrud (1964).1 Studios were reluctant to engage a director who made such difficult films so inefficiently or, rather, made such slow films so slowly. The fallow periods between feature films, however, obliged Dreyer to undertake other kinds of work. -

![Reviews of Dreyer's VAMPYR [Taken from the Amazon.Com Web Page for the Movie; Remember That for the Most Part These Reviewers Are Not Scholars]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7357/reviews-of-dreyers-vampyr-taken-from-the-amazon-com-web-page-for-the-movie-remember-that-for-the-most-part-these-reviewers-are-not-scholars-2267357.webp)

Reviews of Dreyer's VAMPYR [Taken from the Amazon.Com Web Page for the Movie; Remember That for the Most Part These Reviewers Are Not Scholars]

Reviews of Dreyer's VAMPYR [taken from the amazon.com web page for the movie; remember that for the most part these reviewers are not scholars] Editorial Reviews Amazon.com In this chilling, atmospheric German film from 1932, director Carl Theodor Dreyer favors style over story, offering a minimal plot that draws only partially from established vampire folklore. Instead, Dreyer emphasizes an utterly dreamlike visual approach, using trick photography (double exposures, etc.) and a fog-like effect created by allowing additional light to leak onto the exposed film. The result is an unsettling film that seems to spring literally from the subconscious, freely adapted from the Victorian short story Carmilla by noted horror author Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, about a young man who discovers the presence of a female vampire in a mysterious European castle. There's more to the story, of course, but it's the ghostly, otherworldly tone of the film that lingers powerfully in the memory. Dreyer maintains this eerie mood by suggesting horror and impending doom as opposed to any overt displays of terrifying imagery. Watching Vampyr is like being placed under a hypnotic trance, where the rules of everyday reality no longer apply. As a splendid bonus, the DVD includes The Mascot, a delightful 26-minute animated film from 1934. Created by pioneering animator Wladyslaw Starewicz, this clever film--in which a menagerie of toys and dolls springs to life--serves as an impressive precursor to the popular Wallace & Gromit films of the 1990s. --Jeff Shannon Product Description: Carl Theodor Dreyer's eerie horror classic stars Julian West as a visitor to a remote inn under the spell of an aged, bloodthristy female vampire. -

Three Danish Encounters with a Spiritual Reality: the Miracle of Faith in the Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Ordet (1954), &

1 Three Danish Encounters with a Spiritual Reality: The Miracle of Faith in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Ordet (1954), & Babette’s Feast (1988) The Global Saint—A Working Model William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience compared typical figures from around the world considered saintly figures and concluded that they shared the following in common. While I think there are good reasons to hold James’s conclusions rather tentatively, they do help us begin a conversation about what people expect when they call someone “a saint.” 1. A feeling of being in a wider life than that of this world’s selfish little interests; and a conviction, not merely intellectual, but as it were sensible, of the existence of an Ideal Power. In Christian saintliness this power is always personified as God; but abstract moral ideals, civic or patriotic utopias, or inner visions of holiness or right may also be felt as the true lords and enlargers of our life, in ways which I described in the lecture on the Reality of the Unseen. 2. A sense of the friendly continuity of the ideal power with our own life, and a willing self- surrender to its control. 3. An immense elation and freedom, as the outlines of the confining selfhood melt down. 4. A shifting of the emotional centre towards loving and harmonious affections, towards "yes, yes," and away from "no," where the claims of the non-ego are concerned. These fundamental inner conditions have characteristic practical consequences, as follows:- a. Asceticism. -- The self-surrender may become so passionate as to turn into self-immolation. -

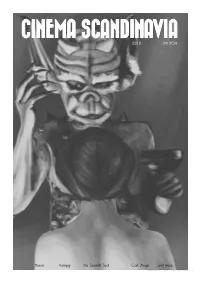

Cinema Scandinavia Issue 2 May 2014 Compressed

CINEMA SCANDINAVIA issue 2 may 2014 Haxan Vampyr The Seventh Seal Carl Dreyer ....and more CINEMA SCANDINAVIA PB CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 1 COVER ART http://jastyoot.deviantart.com/ IN THIS ISSUE Editorial News Haxan and Vampyr Death in the Seventh Seal The Dream of Allan Grey Carl Dreyer Blad af Satans Bog Across the Pond Ordet Released this Month Festivals in May More Information Call for Papers CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 2 THE PARSONS WIDOW CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 2 CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 3 Terje Vigen The Outlaw and his Wife WELCOME Welcome to the second issue of Cinema Scandinavia. This issue looks at the early Scandinavian cinema. Let me provide a brief overview of early Nordic film. Film came to the region in the late 1890s, and movies began to appear in the early 1900s. Danish cinema pioneer Peter Elfelt was the first Dane to make a film, and in the years 1896 through to 1912 he made over 200 films documenting Danish life. His first film was titled Kørsel med Grønlandske Hunde (Travelling with Greenlandic Dogs). During the silent era, Denmark and Sweden were the two biggest Nordic countries on the cinema stage. In Sweden, the greatest directors of the silent era were Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller. Sjöström’s films often made poetic use of the Nordic landscape and played great part in developing powerful studies of character and emotion. Great artistic merit was also found in early Danish cinema. The period around the 1910’s was known as the ‘Golden Age’ of cinema in Denmark, and understandably so. With the increasing length of films there was a growing artistic awareness, which can be seen in Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910). -

Summer Films at the National Gallery of Art

Office of Press and Public Information Fourth Street and Constitution Av enue NW Washington, DC Phone: 202-842-6353 Fax: 202-789-3044 www.nga.gov/press Release Date: June 29, 2009 Summer Films at the National Gallery of Art Film still f rom Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (Albert Lewin, 1951, 35 mm, 122 minutes), at the National Gallery of Art on Friday , August 28, at 2:30 p.m. and Saturday , August 29, at 2:30 p.m. as part of the From Vault to Screen: New Preservation f ilm series. Image courtesy Photof est. This summer, the National Gallery of Art's film program provides a great variety of films combined with concerts and discussions. The six ciné-concerts feature films from the 1920s and 1930s combined with pianists and orchestras in live performance. July's Salute to Le Festival des 3 Continents highlights a collaborative effort between the National Gallery of Art, the Freer Gallery, and the French Embassy to bring avant-garde, classic, and new cinema from Asia, Africa, and Latin America to Washington audiences. The Gallery's annual showcase of recently restored and preserved films, From Vault to Screen, will focus on the collections of La Cinémathèque de Toulouse, Anthology Film Archives, and UCLA Film and Television Archive, among others. A highlight of this series will be the presentation of the restored Manhatta by Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand. This screening concludes with a discussion with Charles Brock, curator of American art, National Gallery of Art, and Bruce Posner, the film historian responsible for the restoration. -

Not Even Past NOT EVEN PAST

The past is never dead. It's not even past NOT EVEN PAST Search the site ... Day of Wrath (1943) Like 0 Tweet by Brian Levack The lm Day of Wrath, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer, is in my opinion the nest lm ever produced on the subject of witchcraft. Dreyer, who is best known for The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), adapted the lm from a drama by the Norwegian playwright Hans Wiers-Jenssen. The lm is based on the accusation and trial of Anne Pedersdotter, the wife of the Lutheran theologian Absalon Pedersen Beyer, for witchcraft. Anne, who was Norway’s most famous witch, was burned at the stake at Bergen in 1590. Day of Wrath takes many liberties with the historical record of Anne’s trial. The lm nonetheless illustrates many of the sources of witchcraft trials in sixteenth- and seventeenth- century Europe, when approximately 45,000 individuals—most of them women—were executed for this crime. The lm introduces a second witchcraft prosecution, that of an older woman, Herlof’s Marthe, who is identied as a friend of Anne’s deceased mother. Marthe conforms much more closely than Anne to the stereotype of the old, poor unmarried witch. The lm also illustrates how tensions within families, especially between mothers and daughters-in-law, could result in witchcraft accusations. In the lm Anne’s mother- in-law, Merete, had never approved of her son, Absalon’s second marriage to the young and beautiful Anne. When Anne falls in love with Martin, Absalon’s son by his rst marriage, the relationship between Anne and Merete deteriorates. -

National Gallery of Art Summer 09 Film Program

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART SUMMER 09 FILM PROGRAM 4th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, DC Mailing address 2000B South Club Drive, Landover, MD 20785 SALUTE TO LE FROM VAULT TO CARL THEODOR ALAIN RESNAIS: GEORGE C. STONEY: FESTIVAL DES SCREEN: NEW FROM NOVEL DREYER: THE THE ELOQUENCE AMERICAN 3 CONTINENTS PRESERVATION TO SCREEN LATE WORKS OF MEMORY DOCUMENTARIAN Manhatta Last at Year Marienbad The Gaucho calendar page cover page four page three page two page one Last at Year Marienbad (Bruce Man with a Movie Camera Manhatta Last at Year Marienbad Pandora and the Flying Dutchman ( P details from SUMMER09 hotofest), P osner), (Bruce ( P Mélo Muriel hotofest), Antonio das Mortes P osner) ( ( P P ( hotofest) hotofest), ( P hotofest), (nostalgia) P ( hotofest) P hotofest) Vampyr ( Vampyr ( ( H P ollis Frampton), hotofest) P ( hotofest), P hotofest), ( P hotofest) El Perro Negro: Stories from the Spanish Civil War preceded by Guernica Sunday September 27 at 4:30 Film Events Media artist Péter Forgács has assembled this unparalleled collage of footage from the Spanish Civil War using the home movies of two talented amateurs, Joan Salvans and Ernesto Diaz Noriega. An extraordinary view of contempo- Stanley William Hayter: rary Spain during the chaotic 1930s, El Perro Negro: Stories from the Spanish From Surrealism to Abstraction Civil War was created for Forgács’ ongoing personal chronicles of twentieth- Sunday July 5 at 2:00 century European history. (Péter Forgács, 2005, HD-Cam, 84 minutes) Guernica combines motifs from Picasso’s epic painting with Paul Éluard’s Three archival films on the British painter and printmaker are featured in poetic text on the besieged Spanish town. -

Michael and Gertrud: Art and the Artist in the Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer David Heinemann

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Heinemann, David ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8946-0422 (2012) Michael and Gertrud: art and the artist in the films of Carl Theodor Dreyer. In: Framing film: cinema and the visual arts. Allen, Steven and Hubner, Laura, eds. Intellect Books, Bristol, UK, pp. 149-164. ISBN 9781841505077. [Book Section] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/13185/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. -

Conversations About Great Films with Diane Christian & Bruce Jackson CARL THEODOR DREYER (3 February 1889, Copenhagen, Denma

Conversations about great films with Diane Christian & Bruce Jackson CARL THEODOR DREYER (3 February 1889, Copenhagen, Denmark—20 March 1968, Copenhagen, Denmark) directed 23 films and wrote 49 screenplays. His last film was Gertrud 1964. He is best known for Vredens dag/Day of Wrath 1943, Vampyr - Der Traum des Allan Grey/Vampyr 1932, and La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc 1928. RUDOLPH MATÉ (21 January 1898, Kraków, Poland—27 October 1964, Hollywood, heart attack) shot 56 films and also directed 31. Some of the films he shot were The Lady from Shanghai 1947 (uncredited), It Had to Be You 1947, Gilda 1946, Cover Girl 1944, Sahara 1943, The Pride of the Yankees 1942, To Be or Not to Be 1942, Stella Dallas 1937, Come and Get It 1936, Dodsworth 1936, LA PASSION DE JEANNE D'ARC Dante's Inferno 1935, Vampyr - Der Traum des Allan Grey 1932, Prix de beauté 1930. Some (1928). 114 min. of his directing credits are The Barbarians 1960, Miracle in the Rain 1956, When Worlds Collide 1951, Union Station 1950, D.O.A. 1950, and It Had to Be You 1947. He was nominated Directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer for 5 best cinematography Oscars: Cover Girl 1944, Sahara 1943, The Pride of the Yankees Written by Joseph Delteil and Carl 1942, That Hamilton Woman 1941 and Foreign Correspondent 1940. Theodor Dreyer Original Music by Ole Schmidt RICHARD EINHORN has “been composing full-time since 1982. His works have been heard at (new score 1982) Lincoln Center, Saratoga Performing Arts Center and other major venues throughout the world. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Bitten Word: Feminine Jouissance, Language, and the Female Vampire Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7vg110pg Author Wilson, Shelby LeAnn Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE BITTEN WORD: FEMININE JOUISSANCE , LANGUAGE, AND THE FEMALE VAMPIRE A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in LITERATURE by Shelby Wilson June 2015 The thesis of Shelby Wilson is approved: Professor Kimberly J. Lau, Chair Professor H. Marshall Leicester, Jr. Professor Carla Freccero Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Shelby Wilson 2015 Table of Contents Introduction: A Quick Nip……………………………………….....1 Wordy Wounds: Richard Crashaw’s Teresian Poems………….8 The Touch of a Spell: “Christabel”………………………………..19 Female Pen, Vampire Fang: Carmilla ……………………………35 Playing off the Page: Carmilla on Film…………………………..53 Conclusion: Shared Bodies, Shared Words……………………..69 Bibliography………………………………………………………...87 iii Abstract Shelby Wilson The Bitten Word: Feminine Jouissance , Language, and the Female Vampire This thesis examines the parallels between the female vampire’s fang (that which punctures phallogocentric discourse as well as other female bodies) and the pointed nib of the female narrator’s pen. Drawing on feminist and psychoanalytic theory, I read the vampiress’ bite as reworking the positions of the female vampire and her companion within a male dominated Symbolic and consider how both women ingest language only to expel it transformed as that which speaks their desire. Carmilla , Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 novella, serves as the referential center of this project and frames my interpretations of Crashaw’s 17 th century Teresian poems, Coleridge’s “Christabel,” and filmic adaptations of Carmilla . -

Fall 2020 Advance Publicity (Sept 1 – Nov 19)

For Immediate Release For more information, Please contact Mary Fessenden At 607.277.4790 Fall 2020 Advance Publicity (Sept 1 – Nov 19) Announcing Virtual Cinema at Cornell Cinema! This Fall Cornell Cinema introduces a virtual cinema program that will give patrons free access to a variety of screenings! There are a limited number of free views available for most titles, so reservations will be required. Reservations can be made starting one week in advance of a title's first playdate. Reservations received before that time will not be processed. Films will be available for about a week, or until the maximum number of views have been reached, whichever comes first. If a film "sells-out," that will be noted on Cornell Cinema’s website, on the title’s individual page. To make a reservation for a film, visit the film’s page on Cornell Cinema’s website for instructions, bearing in mind that these instructions may not be posted until one week in advance of the film’s start date. One film has an unlimited number of views and won’t require a reservation; one requires a pay-per-view. This information will be posted on the title’s individual page on Cornell Cinema’s website (and below). Several films will feature faculty introductions & some will be followed by Q&As with filmmakers via Zoom Webinars For more information visit http://cinema.cornell.edu Ithaca Premiere The Hottest August w/filmmaker Brett Story Q&A on Wed, Sept 9 at 7:30pm Tuesday, September 1 to Thursday, September 10 2019 > USA > Directed by Brett Story Filmed over one month in New York City and its outer boroughs in 2017, the film offers a mirror onto a society on the verge of catastrophe, registering the anxieties, distractions, and survival strategies that preoccupy ordinary lives.