2. the Slow Pulse of the Era: Carl Th. Dreyer's Film Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 13, 2009 (XVIII:1) Carl Theodor Dreyer VAMPYR—DER TRAUM DES ALLAN GREY (1932, 75 Min)

January 13, 2009 (XVIII:1) Carl Theodor Dreyer VAMPYR—DER TRAUM DES ALLAN GREY (1932, 75 min) Directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer Produced by Carl Theodor Dreyer and Julian West Cinematography by Rudolph Maté and Louis Née Original music by Wolfgang Zeller Film editing by Tonka Taldy Art direction by Hermann Warm Special effects by Henri Armand Allan Grey…Julian West Der Schlossherr (Lord of the Manor)…Maurice Schutz Gisèle…Rena Mandel Léone…Sybille Schmitz Village Doctor…Jan Heironimko The Woman from the Cemetery…Henriette Gérard Old Servant…Albert Bras Foreign Correspondent (1940). Some of the other films he shot His Wife….N. Barbanini were The Lady from Shanghai (1947), It Had to Be You (1947), Down to Earth (1947), Gilda (1946), They Got Me Covered CARL THEODOR DREYER (February 3, 1889, Copenhagen, (1943), To Be or Not to Be (1942), It Started with Eve (1941), Denmark—March 20, 1968, Copenhagen, Denmark) has 23 Love Affair (1939), The Adventures of Marco Polo (1938), Stella Directing credits, among them Gertrud (1964), Ordet/The Word Dallas (1937), Come and Get It (1936), Dodsworth (1936), A (1955), Et Slot i et slot/The Castle Within the Castle (1955), Message to Garcia (1936), Charlie Chan's Secret (1936), Storstrømsbroen/The Storstrom Bridge (1950), Thorvaldsen Metropolitan (1935), Dressed to Thrill (1935), Dante's Inferno (1949), De nåede færgen/They Caught the Ferry (1948), (1935), Le Dernier milliardaire/The Last Billionaire/The Last Landsbykirken/The Danish Church (1947), Kampen mod Millionaire (1934), Liliom (1934), Paprika (1933), -

Metaphysics – Transcendence – Atheism

"IMAGES" 2021, Vol. XXX, No. 39 METAPHYSICS – TRANSCENDENCE – ATHEISM A product of the nineteenth century, the cinematic arts were born to capture the very material reality present in front of the lens. Erwin Panofsky called this reality “profilmic,” while André Bazin argued that recording the existence of material objects on film fulfilled what he called mankind’s “mummy complex,” the desire to immortalize fleeting entities in the form of images. With time, film outgrew this initial function and began making attempts to depict spiritual realities as well (with films by Carl Theodor Dreyer, Ingmar Bergman, Andrei Tarkovsky, Krzysztof Zanussi, and other artists). First coined by American director and film theorist Paul Schrader to describe the work of Dreyer, Bresson, and Ozu, the phrase “transcendental style” (itself a misnomer, as the term “transcendent style” would be much more fitting here) was soon picked up by fellow authors, who used it to interrogate the transcendent in the work of the three aforementioned directors and other filmmakers (vide: Seweryn Kuśmierczyk’s essay on Tarkovsky and the rich body of literature written on the director). A counterstrain, however, coalesced around neoformalist and cognitivist David Bordwell, who contended that the particular “parametric form,” its style autonomous and autotelic, compelled critics to seek within it a metaphysics that he did not believe could be found in the work of Ozu, Dreyer, or Bresson—a position he elaborated on extensively in his monographs on the work of the former two and essays on films by the latter. Recent Bresson scholarship (vide: Colin Burnett’s monograph) has questioned the validity of this “Schraderian” option even further. -

Lesbianism and the Uncanny in Sheridan Le Fanu's Carmilla

Lesbianism and the Uncanny in Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla Sergio Ramos Torres Trabajo de Fin de Grado en Estudios Ingleses Supervised by Constanza del Río Álvaro Diciembre 2016 Universidad de Zaragoza 0 Contents Introduction 2 1. The vampire in literature and popular culture 5 1.1 Female vampires 10 2. Lesbianism and the uncanny in Carmilla 13 2.1 Contextualisation 13 2.2 Lesbianism and the Uncanny in Carmilla 16 Conclusion 23 Works Cited 25 1 Introduction The figure of the vampire has been present in most cultures, and the meanings and feelings these supernatural creatures represent have been similar across time and space. For human beings they have been a source of fear and superstition, their significance acquiring religious connotations all over the world. The passing of time has modified this ancient horror and the myth has changed little by little, most of the time being softened, giving birth to diverse conceptions and representations that differ a lot from the evil spawn – originating in myth, legend and folklore – that ancient people were afraid of. These creatures have been represented not as part of the human being, but as a nemesis, as the “other”, and as something that is dead but, at the same time, alive, threatening the pure existence of the human by disrupting the carefully constructed borders that civilization has erected between the self and the other, the human and the animal, between life and death. They are, like Rosemary Jackson said, “our relation to death made concrete” (68) and thus, they “disrupt the crucial defining line which separates real life from the unreality of death” (69). -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

![Reviews of Dreyer's VAMPYR [Taken from the Amazon.Com Web Page for the Movie; Remember That for the Most Part These Reviewers Are Not Scholars]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7357/reviews-of-dreyers-vampyr-taken-from-the-amazon-com-web-page-for-the-movie-remember-that-for-the-most-part-these-reviewers-are-not-scholars-2267357.webp)

Reviews of Dreyer's VAMPYR [Taken from the Amazon.Com Web Page for the Movie; Remember That for the Most Part These Reviewers Are Not Scholars]

Reviews of Dreyer's VAMPYR [taken from the amazon.com web page for the movie; remember that for the most part these reviewers are not scholars] Editorial Reviews Amazon.com In this chilling, atmospheric German film from 1932, director Carl Theodor Dreyer favors style over story, offering a minimal plot that draws only partially from established vampire folklore. Instead, Dreyer emphasizes an utterly dreamlike visual approach, using trick photography (double exposures, etc.) and a fog-like effect created by allowing additional light to leak onto the exposed film. The result is an unsettling film that seems to spring literally from the subconscious, freely adapted from the Victorian short story Carmilla by noted horror author Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, about a young man who discovers the presence of a female vampire in a mysterious European castle. There's more to the story, of course, but it's the ghostly, otherworldly tone of the film that lingers powerfully in the memory. Dreyer maintains this eerie mood by suggesting horror and impending doom as opposed to any overt displays of terrifying imagery. Watching Vampyr is like being placed under a hypnotic trance, where the rules of everyday reality no longer apply. As a splendid bonus, the DVD includes The Mascot, a delightful 26-minute animated film from 1934. Created by pioneering animator Wladyslaw Starewicz, this clever film--in which a menagerie of toys and dolls springs to life--serves as an impressive precursor to the popular Wallace & Gromit films of the 1990s. --Jeff Shannon Product Description: Carl Theodor Dreyer's eerie horror classic stars Julian West as a visitor to a remote inn under the spell of an aged, bloodthristy female vampire. -

Three Danish Encounters with a Spiritual Reality: the Miracle of Faith in the Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Ordet (1954), &

1 Three Danish Encounters with a Spiritual Reality: The Miracle of Faith in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Ordet (1954), & Babette’s Feast (1988) The Global Saint—A Working Model William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience compared typical figures from around the world considered saintly figures and concluded that they shared the following in common. While I think there are good reasons to hold James’s conclusions rather tentatively, they do help us begin a conversation about what people expect when they call someone “a saint.” 1. A feeling of being in a wider life than that of this world’s selfish little interests; and a conviction, not merely intellectual, but as it were sensible, of the existence of an Ideal Power. In Christian saintliness this power is always personified as God; but abstract moral ideals, civic or patriotic utopias, or inner visions of holiness or right may also be felt as the true lords and enlargers of our life, in ways which I described in the lecture on the Reality of the Unseen. 2. A sense of the friendly continuity of the ideal power with our own life, and a willing self- surrender to its control. 3. An immense elation and freedom, as the outlines of the confining selfhood melt down. 4. A shifting of the emotional centre towards loving and harmonious affections, towards "yes, yes," and away from "no," where the claims of the non-ego are concerned. These fundamental inner conditions have characteristic practical consequences, as follows:- a. Asceticism. -- The self-surrender may become so passionate as to turn into self-immolation. -

A Comparative Textual Analysis of Carmilla

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Honors Projects Honors College Spring 5-1-2017 Media Erotics & Adaptation: A Comparative Textual Analysis of Carmilla Rebecca Wait [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Repository Citation Wait, Rebecca, "Media Erotics & Adaptation: A Comparative Textual Analysis of Carmilla" (2017). Honors Projects. 239. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects/239 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Running head: MEDIA EROTICS & ADAPATION 1 Media Erotics & Adaptation: A Comparative Textual Analysis of Carmilla Rebecca K. Wait Honors Project: May 2017 Project Advisors: Sandra Faulkner & Julie Haught Bowling Green State University Submitted to the Honors College Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with University Honors MEDIA EROTICS & ADAPTATION 2 Abstract This project is concerned with understanding the different ways in which Carmilla (1872), a gothic novella, and it’s 2014 web series adaptation differently approach the same basic narrative, especially with regards to their respective representations of individuals who identify as sexual and gender minorities. One of the major functions of importance in this study was to understand the temporality and cultural conditions, which lead to the perceived need for a postmodern adaptation of a pre-modernist text. -

Carl Theodor Dreyer GERTRUD (1964, 119 Min)

October 27, 2009 (XIX:9) Carl Theodor Dreyer GERTRUD (1964, 119 min) Directed and writtenby Carl Theodor Dreyer Based on the play Gertrud by Hjalmar Söderberg Produced by Jørgen Nielsen Original Music by Jørgen Jersild Cinematography by Henning Bendtsen and Arne Abrahamsen Edited by Edith Schlüssel Gertrud’s costumes by Fabielle Nina Pens Rode ... Gertrud Kanning Bendt Rothe ... Gustav Kanning Ebbe Rode ... Gabriel Lidman Baard Owe ... Erland Jansson Axel Strøbye ... Axel Nygen CARL THEODOR DREYER (February 3, 1889, Copenhagen, Denmark—March 20, 1968, Copenhagen, Denmark) has 23 directing credits, among them Gertrud (1964), Ordet/The Word (1955), Et Slot i et slot/The Castle Within the Castle (1955), (1957), Diskret Ophold/Discretion Wanted (1946) and De tre Storstrømsbroen/The Storstrom Bridge (1950), Thorvaldsen skolekammerater (1944). (1949), De nåede færgen/They Caught the Ferry (1948), Landsbykirken/The Danish Church (1947), Kampen mod AXEL STRØBYE (22 February 1928—12 July 2005) appeared in kræften/The Struggle Agasint Cancer (1947), Vandet på 104 films, some of which were Pelle erobreren/Pelle the landet/Water from the Land (1946), Två människor/Two People Conqueror (1987), Babettes gæstebud/Babette’s Feast (1987), De (1945), Vredens dag/Day of Wrath (1943), Mødrehjælpen/Good uanstændige/Topsy Turvy (1983), Olsen-banden går i krig/The Mothers (1942), L’Esclave blanc/Jungla nera (1936), Vampyr - Olsen Gang Goes to War (1978), Takt og tone i Der Traum des Allan Grey (1932), La Passion de Jeanne himmelsengen/1001 Danish Delights (1972), Jag—en älskare/I, a d'Arc/The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Glomdalsbruden/The Lover (1966), Gertrud (1964), Ingen tid til kærtegn/Dear to Me Bride of Glomdal (1926), Du skal ære din hustru/Master of the (1957), and Nålen (1951). -

Trio of Terror Lyz Reblin

e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work Volume 2 Article 6 Number 1 Vol 2, No 1 (2011) September 2014 Trio of Terror Lyz Reblin Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/e-Research Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reblin, Lyz (2014) "Trio of Terror," e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work: Vol. 2: No. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/e-Research/vol2/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reblin: Trio of Terror Trio of Terror e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work, Vol 2, No 1 (2011) HOME ABOUT LOGIN REGISTER SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES Home > Vol 2, No 1 (2011) > Reblin Trio of Terror Lyz Reblin Key words, concepts, and names: Nosferatu, Dracula, Vampyr, Vampire, Horror. Intro From the earliest silent films such as Georges Méliès' The Devil's Castle (1896) to the recent Twilight adaptation, the vampire genre, like the creatures it presents, has been resurrected throughout cinematic history. More than a hundred vampire films have been produced, along with over a dozen Dracula adaptations. The Count has even appeared in films not pertaining to Bram Stoker's original novel. He has been played by the likes of Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee (fourteen times) both John and David Carradine, and even Academy Award winner Gary Oldman. -

Pathos, Performance, Volition: Melodrama's Legacy in the Work of Carl Th

Pathos, Performance, Volition: Melodrama's Legacy in the Work of Carl Th. Dreyer by Amanda Elaine Doxtater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Sandberg, Chair Professor Linda Rugg Professor Linda Williams Fall 2012 Pathos, Performance, Volition: Melodrama's Legacy in the Work of Carl Th. Dreyer © 2012 by Amanda Elaine Doxtater Abstract Pathos, Performance, Volition: Melodrama's Legacy in the Work of Carl Th. Dreyer by Amanda Elaine Doxtater Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Sandberg, Chair This dissertation reads melodrama as an important influence in Carl Th. Dreyer’s work and oeuvre and shows that his work demonstrates melodrama’s relevance to the tradition of Scandinavian art-house, modernist cinema. Dreyer’s work has come to embody a stern and severe aesthetic seen largely as the epitome of artistic restraint rather than indicative of melodramatic expressivity. Dreyer began his career in cinema, however, at the Danish studio Nordisk Films Kompagni in the 1910s when the company became synonymous with early Danish film melodrama and other spectacular, mass-produced, popular fare. Scholars have subsequently labeled this decade “The Golden Age of Danish Melodrama.” Although the standard reception of Dreyer’s work predicates his status as a masterful auteur director upon his decisive break with the company’s production model, its themes, and popular-culture ambitions, this dissertation argues that asserting such a break occludes intriguing continuities in Dreyer’s oeuvre. -

Häxan Vampyr

Häxan & Vampyr Early Scandinavian Horror Film Scandinavian horror has been always known you will be rewarded with a brave, sarcastic and as a stand-out atmospheric genre, which relies on dark performance which includes all the things we peculiarities of Scandinavian culture and history. In know about witches: sabbath, inquisition, tortures, 1922 Danish film director Benjamin Christensen innocent victims, crazy fanatics and many more. An made Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (Witches), authentic material such as historical documents and the film he has become known for and which re- antique engravings suddenly turn into a fictional re- ceived the status of the ‘cult’ one. Ten years later construction of the events that have been described. another famous Danish film director Carl Theo- We can see different stories about witchcraft in me- dor Dreyer made his dark and provoking Vampyr dieval times, how the whole family was destroyed by (Vampire), which didn’t have success when it was accusations in sorcery, the confessions the victims released. Howver, after years, it became one of the make under the tortures are represented in a halluci- most admired of Dreyer’s masterpieces. Both Häx- nation form of a demonic havoc. The devil himself an and Vampyr showed how different Scandinavian looks very impressive, usually monsters look naïve cinematic horror could be, and both of them went and funny in silent era movies, but here the dev- on to inspire many directors to devote their work il does look sinister and real, which makes the film to this mysterious, chilling film genre. Knowing that even more impressive. -

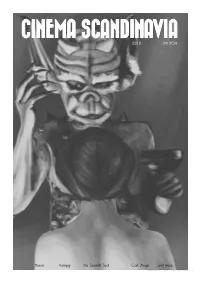

Cinema Scandinavia Issue 2 May 2014 Compressed

CINEMA SCANDINAVIA issue 2 may 2014 Haxan Vampyr The Seventh Seal Carl Dreyer ....and more CINEMA SCANDINAVIA PB CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 1 COVER ART http://jastyoot.deviantart.com/ IN THIS ISSUE Editorial News Haxan and Vampyr Death in the Seventh Seal The Dream of Allan Grey Carl Dreyer Blad af Satans Bog Across the Pond Ordet Released this Month Festivals in May More Information Call for Papers CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 2 THE PARSONS WIDOW CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 2 CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 3 Terje Vigen The Outlaw and his Wife WELCOME Welcome to the second issue of Cinema Scandinavia. This issue looks at the early Scandinavian cinema. Let me provide a brief overview of early Nordic film. Film came to the region in the late 1890s, and movies began to appear in the early 1900s. Danish cinema pioneer Peter Elfelt was the first Dane to make a film, and in the years 1896 through to 1912 he made over 200 films documenting Danish life. His first film was titled Kørsel med Grønlandske Hunde (Travelling with Greenlandic Dogs). During the silent era, Denmark and Sweden were the two biggest Nordic countries on the cinema stage. In Sweden, the greatest directors of the silent era were Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller. Sjöström’s films often made poetic use of the Nordic landscape and played great part in developing powerful studies of character and emotion. Great artistic merit was also found in early Danish cinema. The period around the 1910’s was known as the ‘Golden Age’ of cinema in Denmark, and understandably so. With the increasing length of films there was a growing artistic awareness, which can be seen in Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910).