Microstratigraphic Evidence of in Situ Fire in the Acheulean Strata Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterizing Late Pleistocene and Holocene Stone Artefact Assemblages from Puritjarra Rock Shelter: a Long Sequence from the Australian Desert

© Copyright Australian Museum, 2006 Records of the Australian Museum (2006) Vol. 58: 371–410. ISSN 0067-1975 Characterizing Late Pleistocene and Holocene Stone Artefact Assemblages from Puritjarra Rock Shelter: A Long Sequence from the Australian Desert M.A. SMITH National Museum of Australia, GPO Box 1901, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia [email protected] ABSTRACT. This paper presents the first detailed study of a large assemblage of late Pleistocene artefacts from the central desert. Analysis of the lithics shows show that Puritjarra rock shelter was used more intensively over time, with significant shifts in the character of occupation at 18,000, 7,500 and 800 B.P., reflecting significant re-organization of activities across the landscape. The same generalized flake and core technology appears to have been used for over 30 millennia with only limited change in artefact typology over this period. SMITH, M.A., 2006. Characterizing Late Pleistocene and Holocene stone artefact assemblages from Puritjarra rock shelter: a long sequence from the Australian Desert. Records of the Australian Museum 58(3): 371–410. Excavations at Puritjarra rock shelter provide a rare 2004). Ethno-archaeological studies involving the last opportunity to examine an assemblage of late Pleistocene generation of Aboriginal people to rely on stone artefacts artefacts from central Australia, dating as early as c. 32,000 have been very influential in this shift in perspective (Cane, B.P. This study presents a quantitative analysis of the flaked 1984, 1992; Gould, 1968; Gould et al., 1971; Hayden, 1977, stone artefacts at Puritjarra, comparing the Pleistocene and 1979; O’Connell, 1977). -

Pleistocene Palaeoart of Africa

Arts 2013, 2, 6-34; doi:10.3390/arts2010006 OPEN ACCESS arts ISSN 2076-0752 www.mdpi.com/journal/arts Review Pleistocene Palaeoart of Africa Robert G. Bednarik International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (IFRAO), P.O. Box 216, Caulfield South, VIC 3162, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-95230549; Fax: +61-3-95230549 Received: 22 December 2012; in revised form: 22 January 2013 / Accepted: 23 January 2013 / Published: 8 February 2013 Abstract: This comprehensive review of all currently known Pleistocene rock art of Africa shows that the majority of sites are located in the continent’s south, but that the petroglyphs at some of them are of exceptionally great antiquity. Much the same applies to portable palaeoart of Africa. The current record is clearly one of paucity of evidence, in contrast to some other continents. Nevertheless, an initial synthesis is attempted, and some preliminary comparisons with the other continents are attempted. Certain parallels with the existing record of southern Asia are defined. Keywords: rock art; portable palaeoart; Pleistocene; figurine; bead; engraving; Africa 1. Introduction Although palaeoart of the Pleistocene occurs in at least five continents (Bednarik 1992a, 2003a) [38,49], most people tend to think of Europe first when the topic is mentioned. This is rather odd, considering that this form of evidence is significantly more common elsewhere, and very probably even older there. For instance there are far less than 10,000 motifs in the much-studied corpus of European rock art of the Ice Age, which are outnumbered by the number of publications about them. -

The Aurignacian Viewed from Africa

Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University THE AURIGNACIAN VIEWED FROM AFRICA Christian A. TRYON Introduction 20 The African archeological record of 43-28 ka as a comparison 21 A - The Aurignacian has no direct equivalent in Africa 21 B - Archaic hominins persist in Africa through much of the Late Pleistocene 24 C - High modification symbolic artifacts in Africa and Eurasia 24 Conclusions 26 Acknowledgements 26 References cited 27 To cite this article Tryon C. A. , 2015 - The Aurignacian Viewed from Africa, in White R., Bourrillon R. (eds.) with the collaboration of Bon F., Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe, Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University, P@lethnology, 7, 19-33. http://www.palethnologie.org 19 P@lethnology | 2015 | 19-33 Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University THE AURIGNACIAN VIEWED FROM AFRICA Christian A. TRYON Abstract The Aurignacian technocomplex in Eurasia, dated to ~43-28 ka, has no direct archeological taxonomic equivalent in Africa during the same time interval, which may reflect differences in inter-group communication or differences in archeological definitions currently in use. Extinct hominin taxa are present in both Eurasia and Africa during this interval, but the African archeological record has played little role in discussions of the demographic expansion of Homo sapiens, unlike the Aurignacian. Sites in Eurasia and Africa by 42 ka show the earliest examples of personal ornaments that result from extensive modification of raw materials, a greater investment of time that may reflect increased their use in increasingly diverse and complex social networks. -

Supplementary Table 1: Rock Art Dataset

Supplementary Table 1: Rock art dataset Name Latitude Longitude Earliest age in sampleLatest age in Modern Date of reference Dating methods Direct / indirect Exact Age / Calibrated Kind Figurative Reference sample Country Minimum Age / Max Age Abri Castanet, Dordogne, France 44.999272 1.101261 37’205 36’385 France 2012 Radiocarbon Indirect Minimum Age No Petroglyphs Yes (28) Altamira, Spain 43.377452 -4.122347 36’160 2’850 Spain 2013 Uranium-series Direct Exact Age Unknown Petroglyphs Yes (29) Decorated ceiling in cave Altxerri B, Spain 43.2369 -2.148555 39’479 34’689 Spain 2013 Radiocarbon Indirect Minimum age Yes Painting Yes (30) Anbarndarr I. Australia/Anbarndarr II, -12.255207 133.645845 1’704 111 Australia 2010 Radiocarbon Direct Exact age Yes Beeswax No (31) Australia/Gunbirdi I, Gunbirdi II, Gunbirdi III, Northern Territory Australia Anta de Serramo, Vimianzo, A Coruña, Galicia, 43.110048 -9.03242 6’950 6’950 Spain 2005 Radiocarbon Direct Exact age Yes Painting N/A (32) Spain Apollo 11 Cave, ǁKaras Region, Namibia -26.842964 17.290284 28’400 26’300 Namibia 1983 Radiocarbon Indirect Minimum age Unknown Painted Yes (33) fragments ARN‐0063, Namarrgon Lightning Man, Northern -12.865524 132.814001 1’021 145 Australia 2010 Radiocarbon Direct Exact age Yes Beeswax Yes Territory, Australia (31) Bald Rock, Wellington Range,Northern Territory -11.8 133.15 386 174 Australia 2010 Radiocarbon Direct Exact age Yes Beeswax N/A (31) Australia Baroalba Springs, Kakadu, Northern Territory, -12.677013 132.480901 7’876 7’876 Australia 2010 Radiocarbon -

The Pasts and Presence of Art in South Africa

McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The pasts and presence of art in South Africa Technologies, ontologies and agents Edited by Chris Wingfield, John Giblin & Rachel King The pasts and presence of art in South Africa McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The pasts and presence of art in South Africa Technologies, ontologies and agents Edited by Chris Wingfield, John Giblin & Rachel King with contributions from Ceri Ashley, Alexander Antonites, Michael Chazan, Per Ditlef Fredriksen, Laura de Harde, M. Hayden, Rachel King, Nessa Leibhammer, Mark McGranaghan, Same Mdluli, David Morris, Catherine Namono, Martin Porr, Johan van Schalkwyk, Larissa Snow, Catherine Elliott Weinberg, Chris Wingfield & Justine Wintjes Published by: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Downing Street Cambridge, UK CB2 3ER (0)(1223) 339327 [email protected] www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2020 © 2020 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. The pasts and presence of art in South Africa is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 (International) Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ISBN: 978-1-913344-01-6 On the cover: Chapungu – the Return to Great Zimbabwe, 2015, by Sethembile Msezane, Great Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe. Photograph courtesy and copyright the artist. Cover design by Dora Kemp and Ben Plumridge. Typesetting and layout by Ben Plumridge. Edited for the Institute by James Barrett (Series Editor). Contents Contributors vii Figures -

The Use of Ochre and Painting During the Upper Paleolithic of the Swabian Jura in the Context of the Development of Ochre Use in Africa and Europe

Open Archaeology 2018; 4: 185–205 Original Study Sibylle Wolf*, Rimtautas Dapschauskas, Elizabeth Velliky, Harald Floss, Andrew W. Kandel, Nicholas J. Conard The Use of Ochre and Painting During the Upper Paleolithic of the Swabian Jura in the Context of the Development of Ochre Use in Africa and Europe https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2018-0012 Received June 8, 2017; accepted December 13, 2017 Abstract: While the earliest evidence for ochre use is very sparse, the habitual use of ochre by hominins appeared about 140,000 years ago and accompanied them ever since. Here, we present an overview of archaeological sites in southwestern Germany, which yielded remains of ochre. We focus on the artifacts belonging exclusively to anatomically modern humans who were the inhabitants of the cave sites in the Swabian Jura during the Upper Paleolithic. The painted limestones from the Magdalenian layers of Hohle Fels Cave are a particular focus. We present these artifacts in detail and argue that they represent the beginning of a tradition of painting in Central Europe. Keywords: ochre use, Middle Stone Age, Swabian Jura, Upper Paleolithic, Magdalenian painting 1 The Earliest Use of Ochre in the Homo Lineage Modern humans have three types of cone cells in the retina of the eye. These cells are a requirement for trichromatic vision and hence, a requirement for the perception of the color red. The capacity for trichromatic vision dates back about 35 million years, within our shared evolutionary lineage in the Catarrhini subdivision of the higher primates (Jacobs, 2013, 2015). Trichromatic vision may have evolved as a result of the benefits for recognizing ripe yellow, orange, and red fruits in front of a background of green foliage (Regan et al., Article note: This article is a part of Topical Issue on From Line to Colour: Social Context and Visual Communication of Prehistoric Art edited by Liliana Janik and Simon Kaner. -

Preliminary Study of a Prehistoric Site in Northern Laos

Tam Hang Rockshelter: Preliminary Study of a Prehistoric Site in Northern Laos FABRICE DEMETER, THONGSA SAYAVONGKHAMDY, ELISE PATOLE-EDOUMBA, ANNE-SOPHIE COUPEY, ANNE-MARIE BACON, JOHN DE VOS, CHRISTELLE TOUGARD, BOUNHEUANG BOUASISENGPASEUTH, PHONEPHANH SICHANTHONGTIP, AND PHILIPPE DURINGER introduction Prehistoric research in mainland Southeast Asia was initiated by the French with the establishment of the Geological Service of Indochina (GSI) in 1897. The GSI began to study the geology of Tonkin, Yunnan, Laos, and south- ern Indochina before 1919, later extending their knowledge to northern Indo- china and Cambodia. In the meantime, several major Homo erectus findings occurred in the region, which contributed to the palaeoanthropological debate that prevailed in the 1930s. These discoveries did not involve French but rather Dutch and German scientists. In 1889, E. Dubois discovered Pithecanthropus erectus on the island of Java in Indonesia (Dubois 1894); then in 1929, W. Z. Pei found Sinanthropus pekinensis at Zhoukoudian in China (Weidenreich 1935), while G.H.R. von Koenigswald discovered additional erectus remainsinJava(vonKoe- nigswald 1936). In response, the GSI refocused on the palaeontology and palaeoanthropology of the region, until the cessation of fieldwork activities in 1945 due to the beginning of the war with Japan. Jacques Fromaget joined the GSI in 1923 and conducted tremendous excava- tions in northern Laos and Vietnam as if motivated by the desire to discover some Indochinese hominid remains. Similar to many of his geologist colleagues around the world, Fromaget was not only interested in soil formations but he was also concerned about prehistory. Along with GSI members, M. Colani, E. Fabrice Demeter is a‰liated with the Unite´ Ecoanthropologie et Ethnobiologie, Muse´ede l’Homme, Paris, France. -

Ground Stone Lithic Artifact Breakage Patterns Material Type

Figure 40. Projectile Points from Test Units. a) Point fragment from TV 2, Levell; b-c) Point fragments from TV 2, Level 2. b a c o 3 I centimeters (Figure 39h). The opposite end ofthe scraper was also Lithic Artifact Breakage Patterns used as a wedge. It exhibits heavy bidirectional step fracturing, scaling, and is burinated along one edge. Numerous debitage appear to represent broken frag The other uniface was also produced on a thick flake ments, and although some of the retouched tools are blank; however, it consists of a distal fragment with also broken, none exhibit recent breaks. The question unifacial retouched along two lateral edge margins. is, what processes cause the debitage breakage pat This artifact does exhibit metal scratches (Figure 39i). terns at the site? Researchers have identified several factors that can affect debitage breakage patterns. The four projectile points consist of broken fragments. These include material type, reduction stage, burn Two of these are small base fragments (Figure 40a-b) ing, and various post-depositional processes. Each of and a midsection that could represent Fairland dart these factors will be evaluated in respect to the site debitage assemblage. points (e.g., see Turner and Hester 1993: 117). That is, they appear to be characterized by an expanding and concave base. The other point is a Perdiz arrow point Material Type with a broken base (Figure 40c) (e.g., see Turner and Hester 1993:227). None of the points exhibit any ob The fracture characteristics of a specific material type vious evidence of post-depositional damage. -

5.2UNIT FIVE Superstructure Art Expressive Culture Fall19

5.2 Superstructure: Art and Expressive Culture Focus on Horticultural Societies 1 Superstructure: Art and Expressive Culture Overview: This section covers aspects from the Cultural Materialist theory that relate to Superstructure: the beliefs that support the system. Topics include: Religion, Art, Music, Sports, Medicinal practices, Architecture. 2 ART M0010862 Navajo sand-painting, negative made from postcard Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images [email protected] http://wellcomeimages.org Navajo sand-painting, negative made from postcard, "All publication rights reserved. Apply to J.R. Willis, Gallup, N.M. Kodaks-Art Goods" (U.S.A.) Painting Published: - Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only license CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Key Terms & Concepts • Art • Visual arts • Anthropology of art • The problem of art • Purpose of art • Non-motivated purposes of art: basic human instinct, experience of the mysterious, expression of the imagination, ritualistic & symbolic • Motivated purposes of art: communication, entertainment, political, “free zone”, social inquiry, social causes, psychological/healing, propaganda/commercialism, fitness indicator • Paleolithic art: Blombos cave, figurative art, cave paintings, monumental open air art, petroglyphs • Tribal art: ethnographic art, “primitive art”, African art, Art of the Americas, Oceanic art • Folk art: Antique folk art, Contemporary folk art 3 • Indigenous Australian art: rock painting, Dot painting, Dreamtime, symbols • Sandpainting: Navajo, Tibetan Buddhist mandalas • Ethnomusicology • Dance • Native American Graves Protection And Repatriation Act (NAGPRA): cultural items Art Clockwise from upper left: a self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh; a female ancestor figure by a Chokwe artist; detail from The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli; and an Okinawan Shisa lion. -

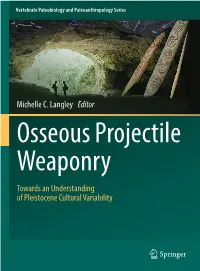

Michelle C. Langley Editor

Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology Series Michelle C. Langley Editor Osseous Projectile Weaponry Towards an Understanding of Pleistocene Cultural Variability Osseous Projectile Weaponry Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology Series Edited by Eric Delson Vertebrate Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History New York, NY 10024,USA [email protected] Eric J. Sargis Anthropology, Yale University New Haven, CT 06520,USA [email protected] Focal topics for volumes in the series will include systematic paleontology of all vertebrates (from agnathans to humans), phylogeny reconstruction, functional morphology, Paleolithic archaeology, taphonomy, geochronology, historical biogeography, and biostratigraphy. Other fields (e.g., paleoclimatology, paleoecology, ancient DNA, total organismal community structure) may be considered if the volume theme emphasizes paleobiology (or archaeology). Fields such as modeling of physical processes, genetic methodology, nonvertebrates or neontology are out of our scope. Volumes in the series may either be monographic treatments (including unpublished but fully revised dissertations) or edited col- lections, especially those focusing on problem-oriented issues, with multidisciplinary coverage where possible. Editorial Advisory Board Ross D. E. MacPhee (American Museum of Natural History), Peter Makovicky (The Field Museum), Sally McBrearty (University of Connecticut), Jin Meng (American Museum of Natural History), Tom Plummer (Queens College/CUNY). More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/6978 -

The Rock Shelter of Kerbizien in Huelgoat Un Visage Original Du Tardiglaciaire En Bretagne : Les Occupations Aziliennes Dans L’Abri-Sous-Roche De Kerbizien À Huelgoat

PALEO Revue d'archéologie préhistorique 25 | 2014 Varia An original settlement during the Tardiglacial in Brittany: the rock shelter of Kerbizien in Huelgoat Un visage original du Tardiglaciaire en Bretagne : les occupations aziliennes dans l’abri-sous-roche de Kerbizien à Huelgoat Grégor Marchand, Jean-Laurent Monnier, François Pustoc’h and Laurent Quesnel Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/paleo/3012 DOI: 10.4000/paleo.3012 ISSN: 2101-0420 Publisher SAMRA Printed version Date of publication: 28 December 2014 Number of pages: 125-168 ISSN: 1145-3370 Electronic reference Grégor Marchand, Jean-Laurent Monnier, François Pustoc’h and Laurent Quesnel, « An original settlement during the Tardiglacial in Brittany: the rock shelter of Kerbizien in Huelgoat », PALEO [Online], 25 | 2014, Online since 02 June 2016, connection on 07 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/paleo/3012 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/paleo.3012 This text was automatically generated on 7 July 2020. PALEO est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. An original settlement during the Tardiglacial in Brittany: the rock shelter ... 1 An original settlement during the Tardiglacial in Brittany: the rock shelter of Kerbizien in Huelgoat Un visage original du Tardiglaciaire en Bretagne : les occupations aziliennes dans l’abri-sous-roche de Kerbizien à Huelgoat Grégor Marchand, Jean-Laurent Monnier, François Pustoc’h and Laurent Quesnel It is particularly gratifying to us to thank Mrs Anne-Marie Mazurier (owner of the land) and Jean-Michel Moullec for his valuable guidance on his work. -

Paleoanthropology Society Meeting Abstracts, Minneapolis, Mn, 12-13 April 2011

PALEOANTHROPOLOGY SOCIETY MEETING ABSTRACTS, MINNEAPOLIS, MN, 12-13 APRIL 2011 The Role of Paleosol Carbon Isotopes in Reconstructing the Aramis Ardipithecus ramidus habitat: Woodland or Grassland? Stanley H. Ambrose, Department of Anthropology, University of Illinois, Urbana, USA Giday WoldeGabriel, Environmental Sciences Division, Los Alamos National Laboratory, USA Tim White, Human Evolution Research Center, University of California, Berkeley, USA Gen Suwa, The University Museum, University of Tokyo, JAPAN Paleosols (fossil soils) were sampled across a 9km west to east curvilinear transect of the Aramis Member of the Sagantole Formation in the Middle Awash Valley. Paleosol carbon isotope ratios are interpreted as reflecting floral habitats with 30% to 70%4 C grass biomass, representing woodlands to wooded grasslands (WoldeGabriel et al. Science 326: 65e1–5, 2009). Pedogenic carbonate carbon and oxygen isotope ratios increase from west to east, reflecting grassier, drier habitats on the east, where Ardipithecus ramidus fossils are absent. These data are consistent with diverse lines of geological, paleontological, anatomical, and dental isotopic evidence for the character and distribution of floral habitats associated with Ardipithecus 4.4 Ma (White et al. Science 326: 87–93, 2009). Cerling et al. (Science 328: 1105-d, 2010) presented a new model for interpreting soil carbon isotopes from Aramis. They concluded that Ardipithecus occupied mainly wooded to open grasslands with less than 25% trees and shrubs and narrow strips of riparian woodlands. Geological and pale- ontological evidence for fluviatile deposition and riparian habitats is absent at Aramis. Their isotopic model contradicts all previously published paleosol carbon isotope-based reconstructions of tropical fossil sites, including all previous publications by six coauthors of Cerling et al.