Pdf Salita and Foreman: a Renaissance for Jewish Boxing?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SERGIO MARTINEZ (ARGENTINA) WON TITLE: September 15, 2012 LAST DEFENCE: April 27, 2013 LAST COMPULSORY : September 15, 2012 by Chavez

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL R A T I N G S JULY 2013 José Sulaimán Chagnon President VICEPRESITENTS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR TREASURER KOVID BHAKDIBHUMI, THAILAND CHARLES GILES, GREAT BRITAIN HOUCINE HOUICHI, TUNISIA MAURICIO SULAIMÁN, MEXICO JUAN SANCHEZ, USA REX WALKER, USA JU HWAN KIM, KOREA BOB LOGIST, BELGIUM LEGAL COUNSELORS EXECUTIVE LIFETIME HONORARY ROBERT LENHARDT, USA VICE PRESIDENTS Special Legal Councel to the Board of Governors JOHN ALLOTEI COFIE, GHANA of the WBC NEWTON CAMPOS, BRAZIL ALBERTO LEON, USA BERNARD RESTOUT, FRANCE BOBBY LEE, HAWAII YEWKOW HAYASHI, JAPAN Special Legal Councel to the Presidency of the WBC WORLD BOXING COUNCIL 2013 RATINGS JULY 2013 HEAVYWEIGHT +200 Lbs +90.71 Kgs VITALI KLITSCHKO (UKRAINE) WON TITLE: October 11, 2008 LAST DEFENCE: September 8, 2012 LAST COMPULSORY : September 10, 2011 WBA CHAMPION: Wladimir Klitschko Ukraine IBF CHAMPION: Wladimir Klitschko Ukraine WBO CHAMPION: Wladimir Klitschko Ukraine Contenders: WBC SILVER CHAMPION: Bermane Stiverne Canada WBC INT. CHAMPION: Seth Mitchell US 1 Bermane Stiverne (Canada) SILVER 2 Seth Mitchell (US) INTL 3 Chris Arreola (US) 4 Magomed Abdusalamov (Russia) USNBC 5 Tyson Fury (GB) 6 David Haye (GB) 7 Manuel Charr (Lebanon/Syria) INTL SILVER / MEDITERRANEAN/BALTIC 8 Kubrat Pulev (Bulgaria) EBU 9 Tomasz Adamek (Poland) 10 Johnathon Banks (US) 11 Fres Oquendo (P. Rico) 12 Franklin Lawrence (US) 13 Odlanier Solis (Cuba) 14 Eric Molina (US) NABF 15 Mark De Mori (Australia) 16 Luis Ortiz (Cuba) FECARBOX 17 Juan Carlos Gomez (Cuba) 18 Vyacheslav Glazkov (Ukraine) -

April-2014.Pdf

BEST I FACED: MARCO ANTONIO BARRERA P.20 THE BIBLE OF BOXING ® + FIRST MIGHTY LOSSES SOME BOXERS REBOUND FROM MARCOS THEIR INITIAL MAIDANA GAINS SETBACKS, SOME DON’T NEW RESPECT P.48 P.38 CANELO HALL OF VS. ANGULO FAME: JUNIOR MIDDLEWEIGHT RICHARD STEELE WAS MATCHUP HAS FAN APPEAL ONE OF THE BEST P.64 REFEREES OF HIS ERA P.68 JOSE SULAIMAN: 1931-2014 ARMY, NAV Y, THE LONGTIME AIR FORCE WBC PRESIDENT COLLEGIATE BOXING APRIL 2014 WAS CONTROVERSIAL IS ALIVE AND WELL IN THE BUT IMPACTFUL SERVICE ACADEMIES $8.95 P.60 P.80 44 CONTENTS | APRIL 2014 Adrien Broner FEATURES learned a lot in his loss to Marcos Maidana 38 DEFINING 64 ALVAREZ about how he’s FIGHT VS. ANGULO perceived. MARCOS MAIDANA THE JUNIOR REACHED NEW MIDDLEWEIGHT HEIGHTS BY MATCHUP HAS FAN BEATING ADRIEN APPEAL BRONER By Doug Fischer By Bart Barry 67 PACQUIAO 44 HAPPY FANS VS. BRADLEY II WHY WERE SO THERE ARE MANY MANY PEOPLE QUESTIONS GOING PLEASED ABOUT INTO THE REMATCH BRONER’S By Michael MISFORTUNE? Rosenthal By Tim Smith 68 HALL OF 48 MAKE OR FAME BREAK? REFEREE RICHARD SOME FIGHTERS STEELE EARNED BOUNCE BACK HIS INDUCTION FROM THEIR FIRST INTO THE IBHOF LOSSES, SOME By Ron Borges DON’T By Norm 74 IN TYSON’S Frauenheim WORDS MIKE TYSON’S 54 ACCIDENTAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY CONTENDER IS FLAWED BUT CHRIS ARREOLA WORTH THE READ WILL FIGHT By Thomas Hauser FOR A TITLE IN SPITE OF HIS 80 AMERICA’S INCONSISTENCY TEAMS By Keith Idec INTERCOLLEGIATE BOXING STILL 60 JOSE THRIVES IN SULAIMAN: THE SERVICE 1931-2014 ACADEMIES THE By Bernard CONTROVERSIAL Fernandez WBC PRESIDENT LEFT HIS MARK ON 86 DOUGIE’S THE SPORT MAILBAG By Thomas Hauser NEW FEATURE: THE BEST OF DOUG FISCHER’S RINGTV.COM COLUMN COVER PHOTO BY HOGAN PHOTOS; BRONER: JEFF BOTTARI/GOLDEN BOY/GETTY IMAGES BOY/GETTY JEFF BOTTARI/GOLDEN BRONER: BY HOGAN PHOTOS; PHOTO COVER By Doug Fischer 4.14 / RINGTV.COM 3 DEPARTMENTS 30 5 RINGSIDE 6 OPENING SHOTS Light heavyweight 12 COME OUT WRITING contender Jean Pascal had a good night on 15 ROLL WITH THE PUNCHES Jan. -

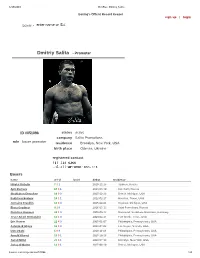

Dmitriy Salita

6/18/2019 BoxRec: Dmitriy Salita Boxing's Official Record Keeper sign up | login enter name or ID# boxer ▾ Dmitriy Salita - Promoter ID #051096 status active company Salita Promotions role boxer promoter residence Brooklyn, New York, USA birth place Odessa, Ukraine registered contact Boxers name w-l-d last 6 debut residence Nikolai Buzolin 7 3 1 2010-12-15 Tyumen, Russia Apti Davtaev 17 0 1 2013-03-30 Kurchaloi, Russia Shohjahon Ergashev 16 0 0 2015-12-23 Detroit, Michigan, USA Bakhtiyar Eyubov 14 1 1 2012-02-17 Houston, Texas, USA Jermaine Franklin 18 0 0 2015-04-04 Saginaw, Michigan, USA Elena Gradinar 9 1 0 2016-05-13 Saint Petersburg, Russia Christina Hammer 24 1 0 2009-09-12 Dortmund, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany Jesse Angel Hernandez 12 3 0 2009-02-14 Fort Worth, Texas, USA Eric Hunter 21 4 0 2005-01-07 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Aslambek Idigov 16 0 0 2013-07-02 Las Vegas, Nevada, USA Izim Izbaki 1 0 0 2018-11-16 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Arnold Khegai 15 0 1 2015-10-28 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Jarrell Miller 23 0 1 2009-07-18 Brooklyn, New York, USA Jarico O'Quinn 12 0 1 2015-04-10 Detroit, Michigan, USA boxrec.com/en/promoter/51096 1/4 6/18/2019 BoxRec: Dmitriy Salita name w-l-d last 6 debut residence Samuel Peter 38 7 0 2001-02-06 Las Vegas, Nevada, USA Nikolai Potapov 20 1 1 2010-03-13 Brooklyn, New York, USA Umar Salamov 24 1 0 2012-12-15 Henderson, Nevada, USA Elena Saveleva 5 1 0 2017-06-23 Pushkino, Russia Claressa Shields 9 0 0 2016-11-19 Flint, Michigan, USA Vladimir Shishkin 8 0 0 2016-07-31 Serpukhov, -

Pam Use Post-Gazette 5-28-10.Pmd

VOL. 114 - NO. 22 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, MAY 28, 2010 $.30 A COPY Memorial Day Lombardo Family Hosts Event Raising $45,000 for 3 Charities Observance May 31, 2010 The Lombardo’s Family FOR THOSE WHO celebrated the Vincent’s Night Club 24th anniversary with a charity gala at Vincent’s and Lombardo’s in HAVE SERVED Randolph, on Wednesday May 19th. As they do every year, the Lombardo’s Family annually hosted three chari- ties at this gala ball. The family picks up 100% of the expense for the entertain- ment, food & liquor. In re- turn, guests are asked to donate a minimum of $65 per person to one of the three featured charities. This year’s highlighted charities included the East Boston Harborside Commu- nity Center, Randolph Youth Softball/Baseball Associa- tion, and The South Shore YMCA. The event pulled more than 500 people and A day of prayer and remembrance for raised $45,000 for the three charities. This years’ event East Boston Harborside Community Center Michael those who died so that we may live in peace. featured entertained by Sulprizio, Chairman of the Board; Mary Catino, Member Stayin’ Alive – One Night of of the Board and Immediate Past Chairperson; Fran Riley, the Bee Gees. The quintes- Coordinator of the Harborside Community Center and sential tribute and vocal Vincent Lombardo, CEO of Lombardo Companies. HAZMAT TRUCKS ON match to the Bee Gee’s. Vincent’s, Lombardo’s, and The Harborside is in charge dents improve their quality the Lombardo’s Family are with meeting the educa- of life by empowering and COMMERCIAL STREET proud to host this annual tional, social, cultural and contributing to the commu- A meeting will be held at the Fairmont Battery Wharf main event and they sincerely recreational needs of its ser- nity through civic and volun- ballroom on Wednesday, June 2 at 6:00PM. -

Boxing Band Kings Floyd Mayweather and Miguel Cotto Face-Off On

Boxing Band Kings Floyd Mayweather and Miguel Cotto Face-off on the Silver Screen NCM Believe Occasions, Mayweather Promotions, Golden-boy Promotions, Miguel Cotto Promotions and O’Reilly Vehicle Parts Provide Two Impressive Fits from Nevada to Cinemas Nation-wide in High- Definition on May possibly 5 Centennial, Co-lo. – April 10, 2012 – This Cinco de Mayo, boxing celebrity and seven-time World Champion Floyd “Money” Mayweather will need on current WBA Super-welterweight World Champion Miguel Cotto in the giant screen affair, Ring Kings: Mayweather compared to. Cotto Fight Go on Saturday, May 5 at 9:00 p.m. ET/6:00 p.m. THERAPIST. Broadcast in hd to very nearly 440 cinemas nation-wide from the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Vegas, the highly-anticipated match-up gives lovers a ringside seat as Mayweathersteps up in fat to challenge Cotto for your super-welterweight tournament. Also presented with this card, will undoubtedly be youthful celebrity Canelo Alvarezfacing six-time World Champion Sugar Shane Mosley. Seats for Band Kings: Mayweather compared to. Cotto Fight Live can be found at collaborating theater box workplaces and online at Watch Mayweather vs Alvarez Online. To get a complete set of rates and cinema destinations, look at the NCM Fathom web site (theaters and players are at the mercy of change). Displayed by NCM Believe Occasions, Mayweather Promotions, Golden-boy Promotions, Miguel Cotto Promotionsand O’Reilly Vehicle Pieces, Bands Kings: Mayweather versus. Cotto Fight Live could be the newest boxing function to be broadcast live in select concert halls across the state through NCM’s distinctive Digital Broadcast Network. -

Weights from Thackerville, Oklahoma

Former World Champion Brandon Rios, Trainer of the Year Robert Garcia and Hall of Fame Promoter Bob Arum Conference Call Transcript; Tuesday, October 29, 2013, From Training Camp in Oxnard, California From training camp at the Robert Garcia Boxing Academy in Oxnard, California, we have former world champion Brandon “Bam Bam” Rios and his trainer, “Trainer of the Year” Robert Garcia, and Hall of Fame Promoter Bob Arum. They are here to discuss their upcoming historic battle against Manny Pacquiao and Freddie Roach, taking place Saturday, November 23 and will be produced and distributed live by HBO Pay-Per-View® at 9:00 PM east coast and 6:00 PM west coast time. Brandon will be hosting his only U.S. media workout this Thursday at Robert Garcia’s gym – 1451 Pacific Ave., Oxnard, California, beginning at Noon PT. Joining Brandon at the workout will be Kevin Hart, who is starring in the upcoming Warner Bros. movie “Grudge Match” which will also be starring Sylvester Stallone and Robert DeNiro. Kevin will also be available for interviews at the workout, as will Bob Arum. BOB ARUM: Hello everybody, I don’t know if it’s morning or night but we just got back from the Philippines last night in time for this conference call with Brandon Rios and Robert Garcia. Everyone is pumped and ready to go. The buzz in Asia is just tremendous. Over 70 media members from all over – mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore attended Manny’s media day, and now we shift the focus to America with Brandon Rios on this conference call and his media day on Thursday. -

Audience Insights Guide

CUTMAN: a boxing musical AUDIENCE INSIGHTS Goodspeed’s Audience Insights is made possible through the generosity of GOODSPEED MUSICALS GOODSPEED The Max Showalter Center for Education in Musical Theatre CUTMAN THE CHARACTERS The Norma Terris Theatre May 12 - June 5, 2011 ARI HOFFMAN: The protagonist of Cutman who is a native of Queens, NY and _________ dreams of being the Welterweight Champion of the World. Weighing in at 145lbs, this Jewish boxer has been training with his father Eli since he was a young boy. Ari MUSIC & LYRICS BY struggles to maintain his Jewish identity while searching for boxing recognition and DREW BRODY representation. ELI HOFFMAN: A custodian at the local synagogue who directs all of his passion BOOK BY towards the training of his son, Ari. After leaving his career as cutman to Marvin JARED MICHAEL COSEGLIA Hagler, Eli married Edie, Ari’s mother. Eli trained Ari to be an unstoppable boxer, but he is reluctant to let Ari fight professionally. STORY BY EDIE HOFFMAN: A native of Queens, NY, who is mother to Ari and wife to Eli. Edie JARED MICHAEL COSEGLIA is devout in her Judaism and has owned a bridal shop since 1989. Edie does not & support her son’s ambition to become a professional boxer. CORY GRANT OLIVIA: A student at the Fashion Institute of Technology who comes into the Hoffman’s LIGHTING DESIGN BY lives after taking a window dressing position at Hoffman’s Bridal Shoppe. Olivia finds JASON LYONS herself falling in love with Ari and stands by his decision to fight professionally. -

Shemuel Pagan Looks to Make Impact Inside and Outside the Ring

Shemuel Pagan looks to make impact inside and outside the ring “He can fight on the inside, he can fight on the outside, and he has fast hands…I think he can win a world title…and I think it will be his character that will propel him there.” When that praise is heaped on a fighter by the one and only Teddy Atlas, it should sound the alarm for boxing fans to take notice. The man Atlas is praising and who fight fans should be aware of is Brooklyn, New York’s Shemuel Pagan, who makes his professional debut August 21 in Newark, New Jersey as part of the Tomasz Adamek-Michael Grant undercard. On Tuesday at the Mendez Gym on the corner of 5th Ave. and W. 28th St. in Manhattan, Pagan and his team held a press conference to formally announce that the twenty-two year old will forego his amateur status and turn pro in less than two weeks. Coming to boxing later than most professional fighters, Pagan picked up the sweet science at age thirteen. Trained by his father, who was a former kickboxing and karate champion in his own right, “Shem” quickly became a rising star in the New York City amateur boxing scene. From 2006 to 2010, Pagan rattled off five straight New York Golden Gloves Championships. In doing so, he joined arguably the greatest amateur fighter of all-time, Mark Breland, as the only other fighter who has won five New York Golden Gloves Championship necklaces. Atlas put it best when he bluntly stated, “You don’t win five Golden Gloves if you don’t know how to fight.” But digging deeper into what we can expect from “Shem” stylistically — other than the fact that he knows how to fight — the Puerto-Rican American insists he doesn’t fit one mold. -

Fight 1 Reel A, 9/30/68 Reel-To-Reel 2

Subgroup VI. Audio / Visual Material Series 1. Audio Media Unboxed Reels Reel-to-Reel 1. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 1 Reel A, 9/30/68 Reel-to-Reel 2. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 1 Reel B, 9/30/68 Reel-to-Reel 3. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 2 Reel A, 10/7/68 Reel-to-Reel 4. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 2 Reel B, 10/7/68 Reel-to-Reel 5. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 3 Reel A, 10/14/68 Reel-to-Reel 6. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 3 Reel B, 10/14/68 Reel-to-Reel 7. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 4 Reel A, 10/21/68 Reel-to-Reel 8. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 4 Reel B, 10/21/68 Reel-to-Reel 9. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 5 Reel A, 10/28/68 Reel-to-Reel 10. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 5 Reel B, 10/28/68 Reel-to-Reel 11. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 6 Reel A, 11/4/68 Reel-to-Reel 12. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 6 Reel B, 11/4/68 Reel-to-Reel 13. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 7 Reel A, 11/8/68 Reel-to-Reel 14. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 7 Reel B, 11/8/68 Reel-to-Reel 15. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 8 Reel A, 11/18/68 Reel-to-Reel 16. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 8 Reel B, 11/18/68 Reel-to-Reel 17. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 9 Reel A, 11/25/68 Reel-to-Reel 18. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 9 Reel B, 11/25/68 Reel-to-Reel 19. -

World Cup Fever Hits the North End ITALY WORLD CUP SCHEDULE on TV THIS WEEK

VOL. 114 - NO. 25 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, JUNE 18, 2010 $.30 A COPY World Cup Fever Hits the North End ITALY WORLD CUP SCHEDULE ON TV THIS WEEK. Happy Italy vs. New Zealand - Sunday, June 20 at 10:00AM (ET) ESPN. Slovakia vs. Italy - Thursday, June 24 at 10:00AM (ET) ESPN. Father’s Day from Publisher, Pam Donnaruma and the Staff of the Post-Gazette Fans cheer as Italy scores a goal against Paraguay. The game ended in a tie. Photo taken at Caffe Dello Sport, Hanover Street, North End, Boston. News Briefs by Sal Giarratani Peace Garden Grows in Dorchester’s Clam Point Back in 2007, I moved to Dorchester’s Clam Point in my niece’s home after living for many years across the Neponset Bridge in Quincy. I quickly took to the neighborhood and noticed the little traffic island by Beach and Park Streets next to AAA Appliance Parts. I started planting flowers around the tree and tidying up the little plot of grass. Others in the neighborhood saw it too. I wasn’t the only one who cared about beautifying the community. My uncle Neal Harrington lived up in Uphams Marisa Iocco watches in anticipation. Corner for a quarter century and was always concerned about the betterment of his own neighborhood too. I left the neighborhood in late 2008 but never forgot that plot of grass. I was back there a few weeks ago and it still has that beauty of life in it as well as a cause of reflec- tion for a family who lost a life at that spot. -

World Boxing Council

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL R A T I N G S JUNE 2013 José Sulaimán Chagnon President VICEPRESITENTS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR TREASURER KOVID BHAKDIBHUMI, THAILAND CHARLES GILES, GREAT BRITAIN HOUCINE HOUICHI, TUNISIA MAURICIO SULAIMÁN, MEXICO JUAN SANCHEZ, USA REX WALKER, USA JU HWAN KIM, KOREA BOB LOGIST, BELGIUM LEGAL COUNSELORS EXECUTIVE LIFETIME HONORARY ROBERT LENHARDT, USA VICE PRESIDENTS Special Legal Councel to the Board of Governors JOHN ALLOTEI COFIE, GHANA of the WBC NEWTON CAMPOS, BRAZIL ALBERTO LEON, USA BERNARD RESTOUT, FRANCE BOBBY LEE, HAWAII YEWKOW HAYASHI, JAPAN Special Legal Councel to the Presidency of the WBC WORLD BOXING COUNCIL 2013 RATINGS JUNE 2013 HEAVYWEIGHT +200 Lbs +90.71 Kgs VITALI KLITSCHKO (UKRAINE) WON TITLE: October 11, 2008 LAST DEFENCE: September 8, 2012 LAST COMPULSORY : September 10, 2011 WBA CHAMPION: Wladimir Klitschko Ukraine IBF CHAMPION: Wladimir Klitschko Ukraine WBO CHAMPION: Wladimir Klitschko Ukraine Contenders: WBC SILVER CHAMPION: Bermane Stiverne Canada WBC INT. CHAMPION: Jonathan Banks US 1 Bermane Stiverne (Canada) SILVER 2 Johnathon Banks (US) INTL 3 Chris Arreola (US) 4 Magomed Abdusalamov (Russia) USNBC 5 Seth Mitchell (US) 6 Tyson Fury (GB) 7 David Haye (GB) INTL SILVER / 8 Manuel Charr (Lebanon/Syria) MEDITERRANEAN/BALTIC 9 Kubrat Pulev (Bulgaria) EBU 10 Tomasz Adamek (Poland) 11 Luis Ortiz (Cuba) FECARBOX 12 Franklin Lawrence (US) 13 Odlanier Solis (Cuba) 14 Eric Molina (US) NABF 15 Mark De Mori (Australia) 16 Juan Carlos Gomez (Cuba) 17 Fres Oquendo (P. Rico) 18 Vyacheslav Glazkov (Ukraine) -

Rav Dovid Feinsteinzt”L

44 PHOTOS: AVRAHAM ELBAZ, DOV BERG, FLASH87 IMAGES, JDN, MaTTIS GOLDBERG, SIMCHA WEINMAN, TSEMACH GLENN, TZVI BLUM, YISSOCHOR DUNOFF. Rav Dovid Dovid Rav Feinstein ZT”l 26 Cheshvan 5781 | November 13, 2020 He was a true osnam, a unique, towering Towering godol, whom Hashem placed in our generation to protect us. We have no way of understanding or captur- ing what we have lost. We will try, in these Greatness ~ pages, to paint a few brushstrokes from his long life, cognizant of the fact that we will barely scratch the surface. Moshe, who un- Born to Kedushah til then had Spectacular Rav Dovid was born in the year 1929 felt it neces- in the town of Luban, Russia. He was the sary to stay in oldest son of his illustrious parents, Rav Luban with the Moshe and Rebbetzin Shima. The early beleaguered Yid- Simplicity years of his life were extremely difficult. den so that he could By the time Rav Dovid was born, the ra- tend to their spiritual bidly anti-Semitic Bolshevik government needs, came to the con- BY AVROHOM BIRNbaUM gedolim. There was so much more about of Stalin was tightening its stranglehold on clusion that if he could him that was hidden than what was re- “There are no words to describe his per- Yiddishkeit and was enacting gezeirah af- not be mechanech his chil- vealed. He lived with Hashem in a way that sonality,” said Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky, ter gezeirah in order to terrorize the people dren, he had no choice but only Hashem understood his greatness and rosh yeshivah of the Philadelphia Yeshiva, into relinquishing their Torah observance.