Chopin's Piano Sonata in B Flat Minor, Opus 35

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1946

TANGLEWOOD — LENOX, MASSACHUSETTS SYMPHONY BERKSHIRE FESTIVAL SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Series B AUGUST 1, 3, 4 STEIItWAV it vm Since fhe time of Liszt, the Sfeinway has consistently been, year after year, the medium chosen by an overwhelming number of concert artists to express their art. Eugene List, Mischa Elman and William Kroll, soloists of this Berk- shire Festival, use the Steinway. Significantly enough, the younger artists, the Masters of tomorrow, entrust their future to this world-famous piano — fhey cannot afFord otherwise to en- danger their artistic careers. The Stein- way is, and ever has been, the Glory Road of the Immortals. M. STEINERT & SONS CO. : 162 BOYLSTON ST.. BOSTON Jerome F. Murphy, Prasic/enf • Also Worcester and SpHngfieid MUSIC SHED TANGLEWOOD (Between Stockbridge and Lenox, Massachusetts) NINTH BERKSHIRE FESTIVAL SEASON 1 946 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1946, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, IflC. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Henry B. Sawyer Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Philip R. Allen M. A. De Wolfe Howe John Nicholas Brown Jacob J. Kaplan Alvan T. Fuller Roger I. Lee Jerome D. Greene Bentley W. Warren N. Penrose Hallowell Raymond S. Wilkins Francis W. Hatch Oliver Wolcott TANGLEWOOD ADVISORY COMMITTEE Allan J. Blau G. Churchill Francis George P. Clayson Lawrence K. Miller Bruce Crane James T. Owens -

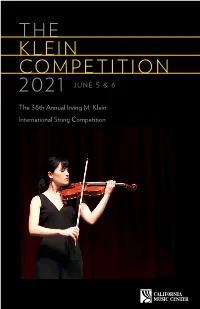

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

CHORAL PROBLEMS in HANDEL's MESSIAH THESIS Presented to The

*141 CHORAL PROBLEMS IN HANDEL'S MESSIAH THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By John J. Williams, B. M. Ed. Denton, Texas May, 1968 PREFACE Music of the Baroque era can be best perceived through a detailed study of the elements with which it is constructed. Through the analysis of melodic characteristics, rhythmic characteristics, harmonic characteristics, textural charac- teristics, and formal characteristics, many choral problems related directly to performance practices in the Baroque era may be solved. It certainly cannot be denied that there is a wealth of information written about Handel's Messiah and that readers glancing at this subject might ask, "What is there new to say about Messiah?" or possibly, "I've conducted Messiah so many times that there is absolutely nothing I don't know about it." Familiarity with the work is not sufficient to produce a performance, for when it is executed in this fashion, it becomes merely a convention rather than a carefully pre- pared piece of music. Although the oratorio has retained its popularity for over a hundred years, it is rarely heard as Handel himself performed it. Several editions of the score exist, with changes made by the composer to suit individual soloists or performance conditions. iii The edition chosen for analysis in this study is the one which Handel directed at the Foundling Hospital in London on May 15, 1754. It is version number four of the vocal score published in 1959 by Novello and Company, Limited, London, as edited by Watkins Shaw, based on sets of parts belonging to the Thomas Coram Foundation (The Foundling Hospital). -

"A Composer's View" in "Music Librarianship in America, Part 4: Music Librarians and Performance"

"A composer's view" in "Music librarianship in America, Part 4: Music librarians and performance" The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Babbitt, Milton. 1991. "A composer's view" in "Music librarianship in America, Part 4: Music librarians and performance". Harvard Library Bulletin 2 (1), Spring 1991: 123-132. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42661672 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 123 A Composer's View Milton Babbitt ince we are gathered in this hall in a spirit of scholarly inquiry, celebrating the S central instrument of such inquiry, I think I can best begin-at least, I dare to begin-by posing a question: "What am I doing here?" I do not come here as a scholar, I come here as a composer. If I seem to be somewhat aporetic, I assure you it is not because I feel in the presence of so many librarians the way Wystan Auden once said he felt in the presence of scientists. He said that he felt like a ragged mendicant in the presence of merchant princes. Well, I don't feel that way: I sim- ply feel like a ragged mendicant. The aporia actually results from pondering the complex problem that must have beset the planning committee in choosing speakers. -

Eichler Columbia 0054D 12688.Pdf

The!Emancipation!of!Memory:!! ! Arnold!Schoenberg!and!the!Creation!of! A"Survivor"from"Warsaw" ! ! ! ! ! ! Jeremy!Adam!Eichler! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Submitted!in!partial!fulfillment!of!the!! requirements!for!the!degree!of!! Doctor!of!Philosophy! in!the!Graduate!School!of!Arts!and!Sciences! ! ! COLUMBIA!UNIVERSITY! ! 2015! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ©!2015! Jeremy!Adam!Eichler! All!rights!reserved! ! ABSTRACT! ! The!Emancipation!of!Memory:!! Arnold!Schoenberg!and!the!Creation!of!A"Survivor"from"Warsaw! ! ! Jeremy!Eichler!! ! ! This!is!a!study!of!the!ways!in!which!the!past!is!inscribed!in!sound.!It!is!also!an! examination!of!the!role!of!concert!music!in!the!invention!of!cultural!memory!in!the!wake!of! the!Second!World!War.!And!finally,!it!is!a!study!of!the!creation!and!early!American!reception! of!A"Survivor"from"Warsaw,!a!cantata!written!in!1947!that!became!the!first!major!musical! memorial!to!the!Holocaust.!It!remains"uniquely!significant!and!controversial!within!the! larger!oeuvre"of!its!composer,!Arnold!Schoenberg!(1874]1951).!! Historians!interested!in!the!chronologies!and!modalities!of!Holocaust!memory!have! tended!to!overlook!music’s!role!as!a!carrier!of!meaning!about!the!past,!while!other!media!of! commemoration!have!received!far!greater!scrutiny,!be!they!literary,!cinematic,!or! architectural.!And!yet,!!A"Survivor"from"Warsaw"predated!almost!all!of!its!sibling!memorials,! crystallizing!and!anticipating!the!range!of!aesthetic!and!ethical!concerns!that!would!define! the!study!of!postwar!memory!and!representation!for!decades!to!come.!It!also!constituted!a! -

The Piano Trio, the Duo Sonata, and the Sonatine As Seen by Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Ravel

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: REVISITING OLD FORMS: THE PIANO TRIO, THE DUO SONATA, AND THE SONATINE AS SEEN BY BRAHMS, TCHAIKOVSKY, AND RAVEL Hsiang-Ling Hsiao, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2017 Dissertation directed by: Professor Rita Sloan School of Music This performance dissertation explored three significant piano trios, two major instrumental sonatas and a solo piano sonatine over the course of three recitals. Each recital featured the work of either Brahms, Tchaikovsky or Ravel. Each of these three composers had a special reverence for older musical forms and genres. The piano trio originated from various forms of trio ensemble in the Baroque period, which consisted of a dominating keyboard part, an accompanying violin, and an optional cello. By the time Brahms and Tchaikovsky wrote their landmark trios, the form had taken on symphonic effects and proportions. The Ravel Trio, another high point of the genre, written in the early twentieth century, went even further exploring new ways of using all possibilities of each instrument and combining them. The duo repertoire has come equally far: duos featuring a string instrument with piano grew from a humble Baroque form into a multifaceted, flexible classical form. Starting with Bach and continuing with Mozart and Beethoven, the form traveled into the Romantic era and beyond, taking on many new guises and personalities. In Brahms’ two cello sonatas, even though the cello was treated as a soloist, the piano still maintained its traditional prominence. In Ravel’s jazz-influenced violin sonata, he treated the two instruments with equal importance, but worked with their different natures and created an innovative sound combination. -

200 Da-Oz Medal

200 Da-Oz medal. 1933 forbidden to work due to "half-Jewish" status. dir. of Collegium Musicum. Concurr: 1945-58 dir. of orch; 1933 emigr. to U.K. with Jooss-ensemble, with which L.C. 1949 mem. fac. of Middlebury Composers' Conf, Middlebury, toured Eur. and U.S. 1934-37 prima ballerina, Teatro Com- Vt; summers 1952-56(7) fdr. and head, Tanglewood Study munale and Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Florence. 1937-39 Group, Berkshire Music Cent, Tanglewood, Mass. 1961-62 resid. in Paris. 1937-38 tours of Switz. and It. in Igor Stravin- presented concerts in Fed. Repub. Ger. 1964-67 mus. dir. of sky's L'histoire du saldai, choreographed by — Hermann Scher- Ojai Fests; 1965-68 mem. nat. policy comm, Ford Found. Con- chen and Jean Cocteau. 1940-44 solo dancer, Munic. Theater, temp. Music Proj; guest lect. at major music and acad. cents, Bern. 1945-46 tours in Switz, Neth, and U.S. with Trudy incl. Eastman Sch. of Music, Univs. Hawaii, Indiana. Oregon, Schoop. 1946-47 engagement with Heinz Rosen at Munic. also Stanford Univ. and Tanglewood. I.D.'s early dissonant, Theater, Basel. 1947 to U.S. 1947-48 dance teacher. 1949 re- polyphonic style evolved into style with clear diatonic ele- turned to Fed. Repub. Ger. 1949- mem. G.D.B.A. 1949-51 solo ments. Fel: Guggenheim (1952 and 1960); Huntington Hart- dancer, Munic. Theater, Heidelberg. 1951-56 at opera house, ford (1954-58). Mem: A.S.C.A.P; Am. Musicol. Soc; Intl. Soc. Cologne: Solo dancer, 1952 choreographer for the première of for Contemp. -

American Experimental Music in West Germany from the Zero Hour To

Beal_Text 12/12/05 5:50 PM Page 8 one The American Occupation and Agents of Reeducation 1945-1950 henry cowell and the office of war information Between the end of World War I and the advent of the Third Reich, many American composers—George Antheil, Marc Blitzstein, Ruth Crawford, Conlon Nancarrow, Roger Sessions, Adolph Weiss, and others (most notably, Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, and Roy Harris, who studied with Nadia Boulanger in France)—contributed to American music’s pres- ence on the European continent. As one of the most adventurous com- posers of his generation, Henry Cowell (1897–1965) toured Europe several times before 1933. Traveling to the continent in early June 1923, Cowell played some of his own works in a concert on the ship, and visiting Germany that fall he performed his new piano works in Berlin, Leipzig, and Munich. His compositions, which pioneered the use of chromatic forearm and fist clusters and inside-the-piano (“string piano”) techniques, were “extremely well received and reviewed in Berlin,” a city that, according to the com- poser, “had heard a little more modern music than Leipzig,” where a hos- tile audience started a fistfight on stage.1 A Leipzig critic gave his review a futuristic slant, comparing Cowell’s music to the noisy grind of modern cities; another simply called it noise. Reporting on Cowell’s Berlin concert, Hugo Leichtentritt considered him “the only American representative of musical modernism.” Many writers praised Cowell’s keyboard talents while questioning the music’s quality.2 Such reviews established the tone 8 Beal_Text 12/12/05 5:50 PM Page 9 for the German reception of unconventional American music—usually performed by the composers themselves—that challenged definitions of western art music as well as stylistic conventions and aesthetic boundaries of taste and technique. -

The Interval Dissonance Rate in Chopin's Études Op. 10, Nos

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-22-2018 The nI terval Dissonance Rate in Chopin’s Études Op. 10, Nos. 1-4: Dissecting Arpeggiation, Chromaticism, and Linear Progressions Nikita Mamedov Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Mamedov, Nikita, "The nI terval Dissonance Rate in Chopin’s Études Op. 10, Nos. 1-4: Dissecting Arpeggiation, Chromaticism, and Linear Progressions" (2018). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4588. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4588 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE INTERVAL DISSONANCE RATE IN CHOPIN’S ÉTUDES OP. 10, NOS. 1-4: DISSECTING ARPEGGIATION, CHROMATICISM, AND LINEAR PROGRESSIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in School of Music by Nikita Mamedov B.M., Rider University, 2013 M.M., Rider University, 2014 August 2018 PREFACE This dissertation has been submitted to fulfill the graduation requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Louisiana State University. This study was conducted under the supervision of Professor Robert Peck in the Music Theory Area. I began my initial research for this project in the summer of 2016. -

Violin Syllabus / 2013 Edition

VVioliniolin SYLLABUS / 2013 EDITION SYLLABUS EDITION © Copyright 2013 The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited All Rights Reserved Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. -

Leichtentritt, Hugo, 1874-1951

Leichtentritt, Hugo, 1874-1951 Nachlass: Hugo Leichtentritt Papers Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress. Identification: ML31.L45 http://infomotions.com/sandbox/liam/pages/httphdllocgovlocmusiceadmusmu012014 Tabellarischer Lebenslauf 1874, 1 Januar in der preußischen Provinz Posen geboren 1891-1894 Eingeschrieben bei der Harvard University 1894-1895 Fortsetzung Musikstudium in Paris 1895-1898 Besuch der Hochschule für Musik in Berlin 1898-1901 Ph.D., in der Philosophie, Universität Berlin; Dissertation mit dem Titel „Reinhard Keiser in seinen Opern“ 1901-1933 Unterrichtet am Klindworth- Scharwenka- Konservatorium Berlin 1901-1933 gab Privatkompositionsunterricht und schrieb Musikkritiken und andere Veröffentlichungen für verschiedene deutsche u. amerikanische Publikationen 1933 verließ Deutschland an der Harvard University anlässlich eines Vortrag 1940 Zurückgezogen von der Harvard University 1940-1944 Dozent: Radcliffe College, Cambridge, Mass., und New York University 1951, 13. November starb in Cambridge, Mass. Musikalische Wirksamkeit und Nachlass Seine persönliche Kompositionen umfassen Lieder und Werke für Klavier solo, Orgel, kleine Instrumentalkombinationen und Orchester. Diese sind hauptsächlich Überkommen durch Notendrucke, Manuskripte, Partituren, Teile und Skizzen. Leichtentritts dramatische Werke sind oft angesehener als seine bedeutendsten Kompositionen: Esther (1923-1926), Kantate, op. 27: Ich bin eine Blume zu Saron (1930) und sein komödiantisches Oper: Der Sizilianer (1915-1918). Seine Kompositionen hat er häufig dazu genutzt durch Rekonstruieren, Änderungen und Veränderung der Anordnung seiner Werkszusammensetzungen und Einbeziehung von Teilen aus Werken anderer Komponisten seine Konzepte für den Unterricht zu illustrieren. Diese sind in seinem Nachlass teilweise als Sub-Serie "Musik anderer Komponisten" neben Partituren und Stimmen von verschiedenen Komponisten wie Bach, Haydn, Händel, Monteverdi und Texte von den deutschen Dichtern wie Richard Dehmel und Friedrich Hölderlin ausführlich repräsentiert. -

William O'hara CV

William O’Hara, Ph.D. Sunderman Conservatory of Music T 608.509.xxxx Gettysburg College B [email protected] Gettysburg, Pennsylvania 17325 Í williamohara.net Appointments Gettysburg College, Sunderman Conservatory of Music Assistant Professor, 2017–present. Tufts University, Department of Music Visiting Lecturer, January 2016–June 2017. Education Harvard University, Department of Music Ph.D., Music Theory, 2017. Committee: Suzannah Clark (supervisor), Alexander Rehding, Christopher Hasty Dissertation: “The Art of Recomposition: Creativity, Aesthetics, and Music Theory.” University of Wisconsin–Madison, Mead Witter School of Music M.A., Music Theory, 2010. Miami University (Oxford, Ohio), Department of Music B.Mus., Music Education, 2008. Publications Book Projects in Recomposition in Music Theory. Manuscript in progress Progress The World Cries Out for Harmony: Amy Beach’s Compositional Voice. Manuscript in progress. Video Games and Popular Music. Essay collection in development, to be co-edited with Jesse Kinne. Journal Articles “Mapping Sound: Play, Performance, and Analysis in Proteus.” Journal of Sound and Music in Games. 1/3 (2020): 35–67. “Music Theory on the Radio: Theme and Temporality in Hans Keller’s First Functional Analysis” Music Analysis 39/1 (2020): 3–49. “Music Theory and the Epistemology of the Internet; or Analyzing Music Under the New Thinkpiece Regime.” Analitica: Rivista online di studi musicali 10 (2018). Recipient of 2020 Adam Krims Award (outstanding publication by a junior scholar), Society for Music Theory Popular Music Interest Group “Flipping the Flip: Responsive Video in the Music Classroom.” Engaging Students 3 (2015). Book Chapters “‘The unmusical fear of wordlessness’: Hans Keller and the Media of Analysis.” In The Ox- ford Handbook of Public Music Theory (forthcoming, 2021), ed.