A Study of Expressionism in Eugene O'neill's Select Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biography of Eugene O'neill

Biography of Eugene O’Neill Trevor M. Wise Eugene Gladstone O’Neill was born on October 16, 1888, at the Barrett hotel in New York city, New York, son of James o’Neill, a well-known matinee idol, and Mary Ellen (Ella) Quinlan. Much of O’Neill’s youth was spent in the wings of the theater as he toured the country with his parents and older brother Jamie, watching his father perform his most famous role—the Count of Monte Cristo. When not touring the country with his family, O’Neill attended Catholic boarding school at St. Aloysius Academy at Mount Saint Vincent in the Bronx borough of New York. he then spent four years at Betts Academy, a non-sectarian prep school in Stamford, Connecticut. O’Neill spent the summers with his family at the Monte Cristo Cottage in New London, Connecticut, the only permanent home O’Neill knew as a child. in 1903, at the age of fifteen, o’Neill became aware of his mother’s morphine addiction and was introduced to alcohol by his brother Jamie, setting him on a path of heavy drinking and alcohol abuse. in the fall of 1906, o’Neill enrolled in princeton University, only to be expelled in the following spring for his poor academic per- formance. in october 1909, o’Neill secretly married Kathleen Jenkins, his first of three wives. Shortly after the wedding, o’Neill set sail for honduras to prospect for gold, but found none. While abroad, O’Neill lived the life of a waterfront derelict, working odd jobs and drinking heavily, until he contracted malaria and was forced to return to the United States. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Eugene O'neill's Strange Interlude

This dissertation has been 61-4507 microfilmed exactly as received WINCHESTER, Otis William, 1933- A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF EUGENE O'NEILL'S STRANGE INTERLUDE. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1961 Speech-Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF EUGENE O'NEILL'S STRANGE INTERLUDE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE ŒADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY OTIS WILLIAM WINCHESTER Tulsa, Oklahoma 1961 A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF EUGENE O'NEILL'S STRANGE INTERLUDE APPROVEDB^ DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PREFACE Rhetoric, a philosophy of discourse and a body of theory for the management of special types of discourse, has been variously defined. Basic to any valid definition is the concept of persuasion. The descrip tion of persuasive techniques and evaluation of their effectiveness is the province of rhetorical criticism. Drama is, in part at least, a rhe torical enterprise. Chapter I of this study establishes a theoretical basis for the rhetorical analysis of drama. The central chapters con sider Eugene O'Neill's Strange Interlude in light of the rhetorical im plications of intent, content, and form. Chapter II deals principally with O'Neill's status as a rhetor. It asks, what are the evidences of a rhetorical purpose in his life and plays? Why is Strange Interlude an especially significant example of O'Neill's rhetoric? The intellectual content of Strange Interlude is the matter of Chapter III. What ideas does the play contain? To what extent is the play a transcript of con temporary thought? Could it have potentially influenced the times? Chapter IV is concerned with the specific manner in which Strange Interlude was used as a vehicle for the ideas. -

The Hairy Ape, Anna Christie, the First Man

https://onemorelibrary.com The Hairy Ape, Anna Christie, The First Man Eugene O'Neill Boni and Liveright, New York, 1922 "THE HAIRY APE" A Comedy of Ancient and Modern Life In Eight Scenes By EUGENE O'NEILL CHARACTERS ROBERT SMITH, "YANK" PADDY LONG MILDRED DOUGLAS HER AUNT SECOND ENGINEER A GUARD A SECRETARY OF AN ORGANIZATION STOKERS, LADIES, GENTLEMEN, ETC. SCENE I SCENE II SCENE III SCENE IV SCENE V SCENE VI SCENE VII SCENE VIII SCENE I SCENE—The firemen's forecastle of a transatlantic liner an hour after sailing from New York for the voyage across. Tiers of narrow, steel bunks, three deep, on all sides. An entrance in rear. Benches on the floor before the bunks. The room is crowded with men, shouting, cursing, laughing, singing—a confused, inchoate uproar swelling into a sort of unity, a meaning—the bewildered, furious, baffled defiance of a beast in a cage. Nearly all the men are drunk. Many bottles are passed from hand to hand. All are dressed in dungaree pants, heavy ugly shoes. Some wear singlets, but the majority are stripped to the waist. The treatment of this scene, or of any other scene in the play, should by no means be naturalistic. The effect sought after is a cramped space in the bowels of a ship, imprisoned by white steel. The lines of bunks, the uprights supporting them, cross each other like the steel framework of a cage. The ceiling crushes down upon the men's heads. They cannot stand upright. This accentuates the natural stooping posture which shovelling coal and the resultant over-development of back and shoulder muscles have given them. -

O'neill Society News

Boston Chosen as Site for Next International Conference in 2020 Fall 2018 O’Neill Society News The official newsletter of the Eugene O’Neill International Society Contents • O’Neill in New York and LA .............1 • Boston selected as the site of the 2020 conference .................................1 • Nancy, France Conference 2018....2 • ALA Conference May 2018 in San Francisco ................................................3 • “One Festival, Two Countries” in Danville, CA & New Ross, Ireland ..4 • News From Our Members ...............5 • ALA Conf 2019 Call for Papers .......5 • O’Neill One-Acts in Japan ................5 • Flock Theatre revives production of Long Day’s Journey into Night ....6 • Photos from O’Neill Events .............7 • Membership Renewals due Jan 1 .7 • MLA Conference participants ........8 • Rob Dowling tours China ................8 New York & Los Angeles Theatres • Upcoming Events in Society ..........8 filled with the sounds of O’Neill New York audiences were given the gift of two major productions of Boston Selected as plays by Eugene O’Neill in the spring of 2018. First, The Iceman Cometh the Site of the 2020 was given a Broadway staging with O’Neill Conference Denzel Washington in the lead role of Theodore “Hickey” Hickman and The membership of the O’Neill direction by George C. Wolfe. The play “laughed more often than I teared up,” Society voted at their May 26, 2018 opened at the Bernard Jacobs Theatre contrasting with other productions that business meeting that the site of the on April 26, and the cast featured some “tend to elicit adjectives like ‘searing’ next Eugene O’Neill International of Broadway’s most accomplished and ‘devastating’ (on the positive side) Conference will be Boston, MA. -

Hughie Page 3

A publication of the Shakespeare Theatre Company ASIDES 2012|2013 SEASON • Issue 3 Richard Schiff and Doug Hughes talk Hughie page 3 Eugene O’Neill’s creative process SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY page 7 A publication of the Shakespeare Theatre Company ASIDES Dear Friend, Hughie is a deceptively simple play. With 3 A Shared Fascination two characters and a single setting, the play is intimate. In a short period of 6 Hughie—Stripping the Soul Naked time, Eugene O’Neill manages to turn by Dr. Yvonne Shafer two nobodies in a late-night hotel lobby into sympathetic characters. As in all of his plays, O’Neill 10 Eugene O’Neill’s New York by Theresa J. Beckhusen makes us question how our own lives are shaped by the people we meet. 12 The Real American Gangster: Arnold Rothstein by Laura Henry Buda When undertaking O’Neill, the devil is in the details. The playwright conveys one layer of the story, the private 14 Play in Process and worlds of the Night Clerk and Erie Smith, solely through Hughie Cast and stage directions. Director Doug Hughes has taken on the Artistic Team formidable task of making these secret worlds just as 15 Coming, Going and palpable as the stage the two men share. Standing Still by Hannah J. Hessel In this issue of Asides, we have included an interview with 17 Drew’s Desk two of our talented artists, Broadway veteran Hughes by Drew Lichtenberg and star of stage and screen Richard Schiff. Also within this issue, Yvonne Shafer, a member of the Eugene O’Neill 19 Hero/Traitor Repertory Society, discusses O’Neill’s creative process, as well as 20 Performance Calendar and Hughie’s unique place within his body of work. -

Eugene O‟Neill: the Constant Presence April 2017

Eugene O‟Neill: The Constant Presence April 2017 SOCIETY BOARD PRESIDENT IN THE U.S., ON STAGE IN IRELAND J. Chris Westgate [email protected] 10th International Conference VICE PRESIDENT July 19-22, pp. 10-13 Robert M. Dowling 1 Central Connecticut State University National University of SECRETARY/TREASURER Ireland, Galway 2 Beth Wynstra [email protected] INTERNATIONAL SECRETARY — ASIA: Haiping Liu [email protected] INTERNATIONAL SECRETARY — EUROPE: Marc Maufort [email protected] 5 GOVERNING BOARD OF DIRECTORS CHAIR: Steven Bloom [email protected] 3 Jackson Bryer [email protected] Eugene O’Neill: Michael Burlingame [email protected] Ireland, the Constant Presence Robert M. Dowling [email protected] Thierry Dubost 4 [email protected] Kurt Eisen Photos: [email protected] 1. Chris Whitaker 2. A. Vincent Scarano Eileen Herrmann 3. Eugene O‘Neill Fdtn. [email protected] 4. Carol Rosegg 5. Stephanie Berger Katie Johnson [email protected] Daniel Larner [email protected] 1. Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Geffen Playhouse, pp. 17-18. Cynthia McCown 2. Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Monte Cristo Cottage, [email protected] pp. 19-20. Anne G. Morgan 3. Shell Shock & The Rescue, Playwrights‘ Theatre, Danville, [email protected] REMEMBERING pp. 28-29. David Palmer THE GELBS 4. The Emperor Jones, Irish Rep, pp. 21-22. [email protected] pp. 3-9 5. The Hairy Ape, The Armory, pp. 14-16. Robert Richter [email protected] EX OFFICIO What‟s Inside IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT Jeff Kennedy Honorary board, special members . .24 President‘s Message . .2 [email protected] Conference Panels . -

The Dramatic Work of Eugene O'neill Considered As to His Use of Literary Dialect As a Unifying Element

THE DRAMATIC WORK OF EUGENE O'NEILL CONSIDERED AS TO HIS USE OF LITERARY DIALECT AS A UNIFYING ELEMENT by Janet M. Marshall A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in the Division of Languages and Literature Morehead State University September 1976 THE DRAMATIC WORK OF EUGENE O ' NEILL CONSIDERED AS TO HIS USE OF LITERARY DIALECT AS A UNIFYING ELEMENT Janet M. Marshall Morehead Sta University, 1976 Director of Thesis On the surface level it must appear to the reader(s} that a writer using literary dialect will do so because of using a dialect, with which the audience is familiar or a dialect which the me mbers of the audience use to a substantial degree . Further, if the motive is one of establishing verisimilitude, the writer will be faithful to the dialect unique to each character, if for no other purpose than being at one with an oral reality of discourse . Many writers of literary dialect--among them such figures as Whittier, Lowell, and Poe, in this country-- have been unsuccessful in the usage of dialect. The burden placed on general or wide audiences, the difficulty of representing the phonology of the dialect , and the distraction of the dialect itself are among major reasons for lack of writer-success in using dialect. 1 2 Krappe and Ives have discussed the nature of dialect and reasons for its lack of success, overall. However, some writers who have not articulated in terms of any literary criticism their employment of dialect have used dialect in a wider perspective. -

A-Moon-For-The-Misbegotten.Pdf

Media Contact: Dawn Kellogg Communications Manager (585) 420-2059 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE GEVA’S 43RD SEASON CONTINUES WITH A MOON FOR THE MISBEGOTTEN Eugene O’Neill’s classic play is a co-production with the Theatre Royal in Rochester’s Sister City of Waterford, Ireland. Rochester, N.Y., March 14, 2016 – A classic drama by America’s only Nobel Prize-winning playwright continues the 2015-2016 ESL Wilson Stage Series as Geva Theatre Center presents A Moon for the Misbegotten by Eugene O’Neill and directed by Ben Barnes in the Elaine P. Wilson Stage from March 29 through April 24. The jaded James Tyrone is on the edge of despair, and the fiercely passionate Josie Hogan is lonely beyond endurance. But on this night, when they meet on a barren patch of earth in the glow of an autumn moon, hope sparks between them. In this bittersweet elegy, two wounded hearts experience the power of redemption—and the saving grace of love. It is a stark look at humanity in its basest and loveliest form by four-time Pulitzer Prize and America’s only Nobel Prize-winning playwright, Eugene O’Neill. When Eugene O’Neill (1888 – 1953) began writing for the stage early in the 20th century, the American theatre was dominated by vaudeville and romantic melodramas. Influenced by Strindberg, Ibsen, and other European playwrights, O’Neill vowed to create a theatre in America, stripped of false sentimentality, which would explore the deepest stirrings of the human spirit. In 1914, he wrote: “I want to be an artist or nothing.” During the 1920s, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for three of his plays – Beyond the Horizon, Anna Christie, and Strange Interlude. -

Strange Interlude by Eugene O’Neill

A publication of the Shakespeare Theatre Company ASIDES 2011|2012 SEASON • Issue 4 Michael Kahn directs Strange Interlude by Eugene O’Neill Michael Kahn talks about his journey to Strange Interlude page 3 The Eugene O’Neill Festival Guide page 20 Celebrating 25 years of Classical Theatre A publication of the Shakespeare Theatre Company Dear Friend, ASIDES This issue of Asides highlights In Pursuit Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude, a play I have wanted to share with 3 In Pursuit of Happiness you for a very long time. This rarely by Norman Allen of performed masterpiece earned O’Neill his third Pulitzer Prize for 5 The Battle at Journey’s End Drama, and played a part in winning him the by Arthur Gelb and Barbara Gelb Nobel Prize in Literature. Its novelistic complexity Happiness and experimental form have rendered it a classic, 8 Eugenic O’Neill and with intriguing possibilities for reinterpretation Michael Kahn’s Journey Strange Interlude and restaging. by Tamsen Wolff to Strange Interlude 10 A Strange Sensation Strange Interlude attracted the attention of by Laura Henry everyone from George Bernard Shaw to the by Norman Allen Marx Brothers. It is a remarkable, intricate work 12 See All Sides of O’Neill with innovative form, and it displays O’Neill by Hannah J. Hessel at the height of his power as a dramatist and 13 Creative Conversations thinker. This issue of Asides examines the ways in which Strange Interlude continues to push the 14 Play in Process boundaries of text, concept and performance. 15 Strange Interlude Cast and Artistic Team STC keeps classical theatre alive by staging works of historical and intellectual stature, and Strange © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. -

E.G.O the Passions of Eugene Gladstone O'neill

E.G.O.: The Passions of Eugene Gladstone O’Neill A full-length play in two acts by Jo Morello Registered WGAW1068640 by Jo Morello 6620 Grand Point Avenue University Park, FL 34201-2125 Phone: 941-351-9688 FAX: 941-306-5042 [email protected] or [email protected] E.G.O.: The Passions of Eugene Gladstone O’Neill, 11/12/2009 ii I- E. G. O.: The Passions of Eugene Gladstone O’Neill A full-length play in two acts by Jo Morello 2M, 2F; some doubling Running time: approx. 55 minutes for each act. Unit set with suggested sets and costumes. Suggested music may be available from author on CD-ROM Synopsis Raised in the theatre as the son of matinee idol James O’Neill, Eugene O’Neill struggled to measure up to and ultimately surpass his father. At 29, he had a wife and son behind him and a life of playwriting ahead— complicated by struggles with alcohol, disease and “the things life has done”—when he met widowed fiction writer Agnes Boulton, 24. Upon his insistence that they must share “an aloneness broken by nothing,” she left her daughter with her parents to marry him—but that aloneness was broken when they had two children of their own, Shane and Oona (the future Mrs. Charlie Chaplin). While married to Agnes, O’Neill won two Pulitzer Prizes (Beyond the Horizon, Anna Christie) and wrote Strange Interlude, which would bring a third Pulitzer. (His fourth Pulitzer, for Long Day’s Journey Into Night, was awarded posthumously.) O’Neill began his own “Interlude” in 1927 with beautiful, domineering, second-rate actress Carlotta Monterey while sending Agnes passionate proclamations of love. -

The Iceman Cometh

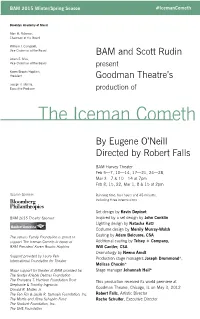

BAM 2015 Winter/Spring Season #IcemanCometh Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM and Scott Rudin Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board present Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Goodman Theatre’s Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer production of The Iceman Cometh By Eugene O’Neill Directed by Robert Falls BAM Harvey Theater Feb 5—7, 10—14, 17—21, 24—28, Mar 3—7 & 10—14 at 7pm Feb 8, 15, 22, Mar 1, 8 & 15 at 2pm Season Sponsor: Running time: four hours and 45 minutes, including three intermissions Set design by Kevin Depinet BAM 2015 Theater Sponsor Inspired by a set design by John Conklin Lighting design by Natasha Katz Costume design by Merrily Murray-Walsh The Jaharis Family Foundation is proud to Casting by Adam Belcuore, CSA support The Iceman Cometh in honor of Additional casting by Telsey + Company, BAM President Karen Brooks Hopkins Will Cantler, CSA Dramaturgy by Neena Arndt Support provided by Laura Pels Production stage managers Joseph Drummond*, International Foundation for Theater Melissa Chacón* Major support for theater at BAM provided by: Stage manager Johannah Hail* The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust This production received its world premiere at Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen Jr. Goodman Theatre, Chicago, IL on May 3, 2012 The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Robert Falls, Artistic Director The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Roche Schulfer, Executive Director The Shubert Foundation, Inc. The SHS Foundation Who’s Who Patrick Andrews Kate Arrington Brian Dennehy Marc Grapey James Harms John Hoogenakker Salvatore Inzerillo John Judd Nathan Lane Andrew Long Larry Neumann, Jr. -

O'neill's the Emperor Jones and the Hairy Ape

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 18 (2003) : 35-48 O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones and The Hairy Ape: The Alienation of the American Anti-hero Eusebio V. Llácer Roughly speaking, realism was a movement that originated in Europe around the 1850s. It represented a reaction against Romanticism. Realists proposed to depict reality as it was, that is to say, art should be an exact imitation of life. Naturalism, we may say, was basically a radicalization of realism. It was in fashion approximately from the 1870s till the 1910s. Naturalism was a social response to Darwinism in science, positivism of Auguste Compte in philosophy and the Industrial Revolution in economy. In realism, the artists were worried about form, thus, they chose themes that could interest the reader of the time such as melodramatic love stories, mainly dealing with the upper classes. On the other hand, naturalists concentrated on themes that could somewhat transgress the moral principles of the growing bourgeoisie, such as prostitution, alcoholism, and adultery in their relationship to determinism: The old ‘naturalism’—or ‘realism’ if you prefer […] no longer applies […] Strindberg […] expressed it by intensifying the method of his time and by foreshadowing both in content and form the methods to come […] Truth, in the theatre as in life, is eternally difficult, just as the easy is the everlasting lie. (O’Neill 1924) The 1920s were the riotous years of the Jim Crow law, lynchings and burnings, but also of the Harlem renaissance in literature. O’Neill was aware in both The Emperor Jones (hereafter EJ) and The Hairy Ape (hereafter HA) that with the emergence of the Black Consciousness Movement, blacks had learned that their position could be established only by confrontation.