Deshpande, Shilpa.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeking Offense: Censorship and the Constitution of Democratic Politics in India

SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ameya Shivdas Balsekar August 2009 © 2009 Ameya Shivdas Balsekar SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA Ameya Shivdas Balsekar, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 Commentators have frequently suggested that India is going through an “age of intolerance” as writers, artists, filmmakers, scholars and journalists among others have been targeted by institutions of the state as well as political parties and interest groups for hurting the sentiments of some section of Indian society. However, this age of intolerance has coincided with a period that has also been characterized by the “deepening” of Indian democracy, as previously subordinated groups have begun to participate more actively and substantively in democratic politics. This project is an attempt to understand the reasons for the persistence of illiberalism in Indian politics, particularly as manifest in censorship practices. It argues that one of the reasons why censorship has persisted in India is that having the “right to censor” has come be established in the Indian constitutional order’s negotiation of multiculturalism as a symbol of a cultural group’s substantive political empowerment. This feature of the Indian constitutional order has made the strategy of “seeking offense” readily available to India’s politicians, who understand it to be an efficacious way to discredit their competitors’ claims of group representativeness within the context of democratic identity politics. -

The 33Rd Annual Conference on South Asia (2004) Paper Abstracts

Single Paper and Individual Panel Abstracts 33rd Annual Conference on South Asia October 15-17, 2004 Note: Abstracts exceeding the 150-word limit were abbreviated and marked with an ellipsis. A. Rizvi, S. Mubbashir, University of Texas at Austin Refashioning Community: The Role of Violence in Redefining Political Society in Pakistan The history of sectarian conflict in Muslim communities in Pakistan goes back to the early days of national independence. The growing presence of extremist Sunni and Shi’a sectarian groups who are advocating for an Islamist State fashioned around their interpretation of Islam has resulted in an escalating wave of violence in the form of targeted killings of activists, religious clerics, Shi’a doctors, professionals and the most recent trend of suicide attacks targeting ordinary civilians. This paper will focus on the rise of sectarian tensions in Pakistan in relation to the changing character of Pakistani State in the Neo-Liberal era. Some of the questions that will be addressed are: What kinds of sectarian subjectivities are being shaped by the migration to the urban and peri-urban centers of Pakistan? What are the ways in which socio-economic grievances are reconfigured in sectarian terms? What are the ways in which violence shapes or politicizes … Adarkar, Aditya, Montclair State University Reflecting in Grief: Yudhishthira, Karna, and the Construction of Character This paper examines the construction of character in the "Mahabharata" through crystalline parallels and mirrorings (described by Ramanujan 1991). Taking Yudhishthira and Karna as an example, we learn much about Karna from the parallel between Karna's dharmic tests and Yudhishthira's on the way to heaven; and several aspects of Yudhishthira's personality (his blinding hatred, his adherence to his worldview) come to the fore in the context of his hatred of and grief over Karna. -

Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons @ Butler University Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 19 Article 5 2006 Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Recommended Citation Sathaye, Adheesh (2006) "Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute," Journal of Hindu- Christian Studies: Vol. 19, Article 5. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1360 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Sathaye: Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhankarkar Institute Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye University of British Columbia ON January 5, 2004, the Bhandarkar Institute, a prominent group of Maharashtrian historians large Sanskrit manuscript library in Pune, was sent a letter to OUP calling for its withdrawal. vandalized because of its involvement in James Apologetically, OUP pulled it from Indian Laine's controversial study of the Maharashtrian shelves on November 21,2003, but this did little king Shivaji. While most of the manuscripts to quell the outrage arising from one paragraph escaped damage, less fortunate was the in Laine's book deemed slanderous to Shivaji academic project of South Asian studies, which and his mother Jijabai: now faces sorpe serious questions. -

Political Economy of a Dominant Caste

Draft Political Economy of a Dominant Caste Rajeshwari Deshpande and Suhas Palshikar* This paper is an attempt to investigate the multiple crises facing the Maratha community of Maharashtra. A dominant, intermediate peasantry caste that assumed control of the state’s political apparatus in the fifties, the Marathas ordinarily resided politically within the Congress fold and thus facilitated the continued domination of the Congress party within the state. However, Maratha politics has been in flux over the past two decades or so. At the formal level, this dominant community has somehow managed to retain power in the electoral arena (Palshikar- Birmal, 2003)—though it may be about to lose it. And yet, at the more intricate levels of political competition, the long surviving, complex patterns of Maratha dominance stand challenged in several ways. One, the challenge is of loss of Maratha hegemony and consequent loss of leadership of the non-Maratha backward communities, the OBCs. The other challenge pertains to the inability of different factions of Marathas to negotiate peace and ensure their combined domination through power sharing. And the third was the internal crisis of disconnect between political elite and the Maratha community which further contribute to the loss of hegemony. Various consequences emerged from these crises. One was simply the dispersal of the Maratha elite across different parties. The other was the increased competitiveness of politics in the state and the decline of not only the Congress system, but of the Congress party in Maharashtra. The third was a growing chasm within the community between the neo-rich and the newly impoverished. -

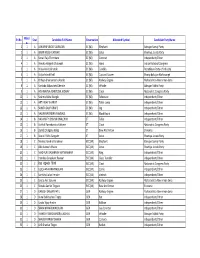

Sr.No.Ward No Seat Candidate Full Name Reservation Allocated

Sr.No. Ward Seat Candidate Full Name Reservation Allocated Symbol Candidate PartyName No 1 1 A ASHWINI VINOD VAIRAGAR SC (W) Elephant Bahujan Samaj Party 2 1 A KIRAN NILESH JATHAR SC (W) Lotus Bhartiya Janata Party 3 1 A Sonali Raju Thombare SC (W) Coconut Independent/Other 4 1 A Renuka Hulgesh Chalwadi SC (W) Hand Indian National Congress 5 1 A Vidya Anil Lokhande SC (W) Candles Republican Party of India (A) 6 1 A Vidya Ashok Patil SC (W) Cup and Saucer Bharip Bahujan Mahasangh 7 1 A Chhaya Bhairavnath Ukarde SC (W) Railway Engine Maharashtra Navnirman Sena 8 1 A Kantabai Balasaheb Dhende SC (W) Whistle Bahujan Mukti Party 9 1 A AISHWARYA ASHUTOSH JADHAV SC (W) Clock Nationalist Congress Party 10 1 A Sushma Rahul Bengle SC (W) Television Independent/Other 11 1 A ARTI VIJAY KHARAT SC (W) Table Lamp Independent/Other 12 1 A SUNITA DILIP ORAPE SC (W) Jug Independent/Other 13 1 A NALINI RAJENDRA KAMBALE SC (W) Black Board Independent/Other 14 1 B NAVANATH SHIVAJI BHALCHIM ST Table Independent/Other 15 1 B Vithhal Ramchandra Kothere ST Clock Nationalist Congress Party 16 1 B Dunda Dongaru Kolap ST Bow And Arrow Shivsena 17 1 B Maruti Palhu Sangade ST Lotus Bhartiya Janata Party 18 1 C Menka Jitendra Karalekar BCC (W) Elephant Bahujan Samaj Party 19 1 C Alka Avinash Khade BCC (W) Lotus Bhartiya Janata Party 20 1 C MADHURI DASHRATH MATWANKAR BCC (W) Ring Independent/Other 21 1 C Hemlata Suryakant Pawaar BCC (W) Glass Tumbler Independent/Other 22 1 C रेखा चंकांत टंगरे BCC (W) Clock Nationalist Congress Party 23 1 C GULSHAN KARIM MULANI BCC (W) -

100 Days Under the New Regime the State of Minorities 100 Days Under the New Regime the State of Minorities

100 Days Under the New Regime The State of Minorities 100 Days Under the New Regime The State of Minorities A Report Edited by John Dayal ISBN: 978-81-88833-35-1 Suggested Contribution : Rs 100 Published by Anhad INDIA HAS NO PLACE FOR HATE AND NEEDS NOT A TEN-YEAR MORATORIUM BUT AN END TO COMMUNAL AND TARGETTED VIOLENCE AGAINST RELIGIOUS MINORITIES A report on the ground situation since the results of the General Elections were announced on16th May 2014 NEW DELHI, September 27th, 2014 The Prime Minister, Mr. Narendra Modi, led by Bharatiya Janata Party to a resounding victory in the general elections of 2014, riding a wave generated by his promise of “development” and assisted by a remarkable mass mobilization in one of the most politically surcharged electoral campaigns in the history of Independent India. When the results were announced on 16th May 2014, the BJP had won 280 of the 542 seats, with no party getting even the statutory 10 per cent of the seats to claim the position of Leader of the Opposition. The days, weeks and months since the historic victory, and his assuming ofice on 26th May 2014 as the 14th Prime Minister of India, have seen the rising pitch of a crescendo of hate speech against Muslims and Christians. Their identity derided,their patriotism scoffed at, their citizenship questioned, their faith mocked. The environment has degenerated into one of coercion, divisiveness, and suspicion. This has percolated to the small towns and villages or rural India, severing bonds forged in a dialogue of life over the centuries, shattering the harmony build around the messages of peace and brotherhood given us by the Suis and the men and women who led the Freedom Struggle under Mahatma Gandhi. -

The New-Age Maratha Warrior

HYDERABAD | FRIDAY, 27 JULY 2018 TAKE TWO 3 . < NEWSMAKER/PRAVIN GAIKWAD: COMMUNITY LEADER Facebook controversies The new-age Maratha warrior hit company where The man at the centre of the socio-political storm brewing in Maharashtra is a leader to it hurts most watch as the country heads towards elections BLOOMBERG declining,” said Brian Wieser, an analyst at Pivotal ABHISHEK WAGHMARE against the “Hindutva” brand professed by the 26 July Research Group. New Delhi, 26 July likes of B M Purandare, and Manohar Bhide. Facebook said it had 1.47 billion daily active users Brahminism and capitalism are the forces Facebook Inc’s scandals are finally hitting the com- in June, compared with the 1.48 billion average of eriods of heightened political polarisa- that exploit the masses, and the progressive pany where it hurts: growth. analysts’ estimates compiled by Bloomberg. The tion and caste-based social movements force of farmers and workers (dominated by the The social-media goliath’s financial performance company’s user base flatlined in its biggest market, in India have two outcomes, say political Maratha community) is the only way to counter had previously seemed immune to fierce criticism of the US and Canada, at 185 million daily users, while Panalysts: regime change and/or the the exploitation, he says. its content policies, its failure to safeguard private declining 1 per cent in Europe to 279 million daily emergence of new political leaders. The sim- A young activist who did not wish to be data, and its changing rules for advertisers. But on users. Overall, average daily users increased 11 per- mering Maratha agitation in Maharashtra has named said Gaikwad has two rare qualities; he Wednesday Facebook reported sales and user growth cent from the period a year earlier. -

Applications Received During 1 to 31 July, 2018

Applications received during 1 to 31 July, 2018 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 31 January, 2018. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 9576/2018-CO/L 01/07/2018 MP STATE TENANT INFORMATION DATA Literary/ Dramatic Uday Gare 2 9577/2018-CO/L 01/07/2018 Shaadi Kab Karoge Literary/ Dramatic Pankaj Rautela 3 9578/2018-CO/SW 01/07/2018 AUTOSHAK Computer Software RAJESH KIRIT MANKAD 4 9579/2018-CO/SW 01/07/2018 star Opticals Computer Software Kalpesh Bornare 5 9580/2018-CO/L 01/07/2018 Design & Fabrication of Groundnut Sheller Literary/ Dramatic Ashish Shyam Raghtate Machine 6 9581/2018-CO/M 01/07/2018 Udi Udi Jane Kata Music Samuel Thapa 7 9582/2018-CO/L 01/07/2018 SAARAL KAVITHAIGAL Literary/ Dramatic VBX PUBLICATION 8 9583/2018-CO/SR 01/07/2018 Akele hum Sound Recording Apurva Singhal, Riya Kumari 9 9584/2018-CO/L 01/07/2018 Ravaayan Literary/ Dramatic Sarthak Arora 10 9585/2018-CO/L 01/07/2018 -

The Condemned Can't Fi

follow us: friday, january 24, 2020 Delhi City Edition thehindu.com 24 pages ț ₹10.00 facebook.com/thehindu twitter.com/the_hindu Pawan Varma is free Top UN court orders India begins T20I series Thiem and Wawrinka to leave JD(U) if he so Myanmar to prevent against New Zealand survive scares; Nadal wishes, says Nitish Rohingya genocide at Auckland today cruises into third round page 12 page 14 page 18 page 20 Printed at . Chennai . Coimbatore . Bengaluru . Hyderabad . Madurai . Noida . Visakhapatnam . Thiruvananthapuram . Kochi . Vijayawada . Mangaluru . Tiruchirapalli . Kolkata . Hubballi . Mohali . Malappuram . Mumbai . Tirupati . lucknow . cuttack . patna NEARBY CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC Virushit Wuhan locked down In full finery Trains and planes indefinitely suspended; travel curbs in neighbouring cities too Agence France-Presse Beijing Indian nurse ‘Peaceful protests will China on Thursday locked tests positive deepen democratic roots’ down some 20 million peo NEW DELHI ple at the epicentre of the An Indian nurse working at Referring to the ongoing new coronavirus outbreak, a hospital in Saudi Arabia agitation against the banning planes and trains tested positive for the novel amended citizenship law and a from leaving in an unprece Coronavirus when she and proposed nationwide National Register of Citizens exercise, dented move aimed at con nearly 100 of her Indian former President Pranab taining the disease, which colleagues, mostly from Mukherjee on Thursday said has spread to other coun Kerala, were screened, the that the “peaceful protests” tries. government said. She is would lead to a deepening of The respiratory virus, being treated at Aseer India’s democratic roots. He 2019nCoV, has claimed 17 On alert: A soldier uses a digital thermometer to check a National Hospital. -

Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 19 Article 5 January 2006 Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sathaye, Adheesh (2006) "Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 19, Article 5. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1360 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Sathaye: Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhankarkar Institute Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye University of British Columbia ON January 5, 2004, the Bhandarkar Institute, a prominent group of Maharashtrian historians large Sanskrit manuscript library in Pune, was sent a letter to OUP calling for its withdrawal. vandalized because of its involvement in James Apologetically, OUP pulled it from Indian Laine's controversial study of the Maharashtrian shelves on November 21,2003, but this did little king Shivaji. While most of the manuscripts to quell the outrage arising from one paragraph escaped damage, less fortunate was the in Laine's book deemed slanderous to Shivaji academic project of South Asian studies, which and his mother Jijabai: now faces sorpe serious questions. -

Urban Cooperative Bank (D- 1)

Urban Cooperative Bank (D- 1) SR. MEMBER DEFAULTER NAME ADDRESS Representative Name Age Gender Representative Address REMARK NO. NO. (Y/N) BHAGYODAYA FRIEND APROCH ROAD, PANDHURNA ROAD, At Post & Tal. Varud, Dist D/1 32 7 URBAN CO-OP BANK LTD, GANESH NAGAR, WARUD, TALUKA Shri Kashikar Pandit Raghuvir M N Amravati WARUD WARUD, DIST. AMRAVATI, PIN 444906 PRABHAT CHOWK, AMRAVATI, TAL. ABHINANDAN URBAN CO-OP. Shri Lunawat Rajendrakumar At Post - Amaravati.Tal Dist- D/1 33 54 AMRAVATI, DIST. AMRAVATI, PIN M N BANK LTD. Kundanmalji Amaravti. 444601 JAISTAMBHA CHOWK, ACHALPUR THE AHCALPUR URBAN CO- D/1 34 69 CAMP., TAL. ACHALPUR-PARATWADA, - N OP BANK LTD. DIST. AMRAVATI, PIN 444806 WARUD URBAN CO-OP. APPROACH ROAD, WARUD, TAL. D/1 35 81 - N BANK LTD. WARUD., DIST. AMRAVATI, PIN 444906 LADHA COMPLEX, OLD COTTON MAHATMA PHULE DIST. Shri Aande Rajendra D/1 36 209 MARKET ROAD, TAL. AMRAVATI, DIST. M At Post - Tal Dist-Amaravati N URBAN CO-OP. BANK LTD. Mahadevrao AMRAVATI, PIN 444601 THE DR. PANJABRAO SHIVAJI NAGAR, TAL. AMRAVATI, D/1 37 1822 DESHMUKH URBAN CO-OP. Shri Barabde Rajesh Haribhau M At Post - Tal Dist-Amaravati N DIST. AMRAVATI, PIN 444601 BANK LTD. AMRAVATI ZILLA PARISHAD CONGRESS NAGAR ROAD, NEAR RLY D/1 38 1823 SHIKSHAK SAHAKARI BANK BRIDGE, AMRAVATI, TAL. AMRAVATI, - N MYDT. DIST. AMRAVATI, PIN 444601 AMRAVATI ZILLA MAHILA JAWAHAR ROAD, TAL. AMRAVATI, Sou Khodke Sulbhatai D/1 39 1829 F At Post, Tal & Dist Amravati N SAHAKARI BANK LTD. DIST. AMRAVATI, PIN 444601 Sanjayrao NIMKAR BUILDING, PANCHSHEEL JANATA SAHAKARI BANK CINEMA ROAD, AMARAVATI, TAL. -

Signature Redacted Signature of Author: Program in Comparative Media Studies 12 May 2009

Indian Comics as Public Culture MASSACHUSETS INSTITUTE By OF TECHNOLOGY Abhimnanyu Das JL0821 B.A. English, Franklin and Marshall College 2005 SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2009 0 2009 Abhimanyu Das. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author: Program in Comparative Media Studies 12 May 2009 Certified by: Signature redacted_ _ _ Henry Jenkins III 67 et d'Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of C dufiarative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Signature redacted Accepted by:_________________ William Charles Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-director, Comparative Media Studies I 2 Indian Comics as Public Culture by Abhimanyu Das Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies on May 12 2009, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT: The Amar Chitra Katha (ACK) series of comic books have, since 1967, dominated the market for domestic comic books in India. In this thesis, I examine how these comics function as public culture, creating a platform around which groups and individuals negotiate and re-negotiate their identities (religious, class, gender, regional, national) through their experience of the mass-media phenomenon of ACK. I also argue that the comics, for the most part, toe a conservative line - drawing heavily from Hindu nationalist schools of thought.