Editors' Introduction to the Roundtable on Intellectual Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeking Offense: Censorship and the Constitution of Democratic Politics in India

SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ameya Shivdas Balsekar August 2009 © 2009 Ameya Shivdas Balsekar SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA Ameya Shivdas Balsekar, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 Commentators have frequently suggested that India is going through an “age of intolerance” as writers, artists, filmmakers, scholars and journalists among others have been targeted by institutions of the state as well as political parties and interest groups for hurting the sentiments of some section of Indian society. However, this age of intolerance has coincided with a period that has also been characterized by the “deepening” of Indian democracy, as previously subordinated groups have begun to participate more actively and substantively in democratic politics. This project is an attempt to understand the reasons for the persistence of illiberalism in Indian politics, particularly as manifest in censorship practices. It argues that one of the reasons why censorship has persisted in India is that having the “right to censor” has come be established in the Indian constitutional order’s negotiation of multiculturalism as a symbol of a cultural group’s substantive political empowerment. This feature of the Indian constitutional order has made the strategy of “seeking offense” readily available to India’s politicians, who understand it to be an efficacious way to discredit their competitors’ claims of group representativeness within the context of democratic identity politics. -

The 33Rd Annual Conference on South Asia (2004) Paper Abstracts

Single Paper and Individual Panel Abstracts 33rd Annual Conference on South Asia October 15-17, 2004 Note: Abstracts exceeding the 150-word limit were abbreviated and marked with an ellipsis. A. Rizvi, S. Mubbashir, University of Texas at Austin Refashioning Community: The Role of Violence in Redefining Political Society in Pakistan The history of sectarian conflict in Muslim communities in Pakistan goes back to the early days of national independence. The growing presence of extremist Sunni and Shi’a sectarian groups who are advocating for an Islamist State fashioned around their interpretation of Islam has resulted in an escalating wave of violence in the form of targeted killings of activists, religious clerics, Shi’a doctors, professionals and the most recent trend of suicide attacks targeting ordinary civilians. This paper will focus on the rise of sectarian tensions in Pakistan in relation to the changing character of Pakistani State in the Neo-Liberal era. Some of the questions that will be addressed are: What kinds of sectarian subjectivities are being shaped by the migration to the urban and peri-urban centers of Pakistan? What are the ways in which socio-economic grievances are reconfigured in sectarian terms? What are the ways in which violence shapes or politicizes … Adarkar, Aditya, Montclair State University Reflecting in Grief: Yudhishthira, Karna, and the Construction of Character This paper examines the construction of character in the "Mahabharata" through crystalline parallels and mirrorings (described by Ramanujan 1991). Taking Yudhishthira and Karna as an example, we learn much about Karna from the parallel between Karna's dharmic tests and Yudhishthira's on the way to heaven; and several aspects of Yudhishthira's personality (his blinding hatred, his adherence to his worldview) come to the fore in the context of his hatred of and grief over Karna. -

Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons @ Butler University Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 19 Article 5 2006 Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Recommended Citation Sathaye, Adheesh (2006) "Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute," Journal of Hindu- Christian Studies: Vol. 19, Article 5. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1360 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Sathaye: Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhankarkar Institute Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye University of British Columbia ON January 5, 2004, the Bhandarkar Institute, a prominent group of Maharashtrian historians large Sanskrit manuscript library in Pune, was sent a letter to OUP calling for its withdrawal. vandalized because of its involvement in James Apologetically, OUP pulled it from Indian Laine's controversial study of the Maharashtrian shelves on November 21,2003, but this did little king Shivaji. While most of the manuscripts to quell the outrage arising from one paragraph escaped damage, less fortunate was the in Laine's book deemed slanderous to Shivaji academic project of South Asian studies, which and his mother Jijabai: now faces sorpe serious questions. -

Political Economy of a Dominant Caste

Draft Political Economy of a Dominant Caste Rajeshwari Deshpande and Suhas Palshikar* This paper is an attempt to investigate the multiple crises facing the Maratha community of Maharashtra. A dominant, intermediate peasantry caste that assumed control of the state’s political apparatus in the fifties, the Marathas ordinarily resided politically within the Congress fold and thus facilitated the continued domination of the Congress party within the state. However, Maratha politics has been in flux over the past two decades or so. At the formal level, this dominant community has somehow managed to retain power in the electoral arena (Palshikar- Birmal, 2003)—though it may be about to lose it. And yet, at the more intricate levels of political competition, the long surviving, complex patterns of Maratha dominance stand challenged in several ways. One, the challenge is of loss of Maratha hegemony and consequent loss of leadership of the non-Maratha backward communities, the OBCs. The other challenge pertains to the inability of different factions of Marathas to negotiate peace and ensure their combined domination through power sharing. And the third was the internal crisis of disconnect between political elite and the Maratha community which further contribute to the loss of hegemony. Various consequences emerged from these crises. One was simply the dispersal of the Maratha elite across different parties. The other was the increased competitiveness of politics in the state and the decline of not only the Congress system, but of the Congress party in Maharashtra. The third was a growing chasm within the community between the neo-rich and the newly impoverished. -

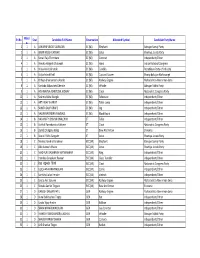

Sr.No.Ward No Seat Candidate Full Name Reservation Allocated

Sr.No. Ward Seat Candidate Full Name Reservation Allocated Symbol Candidate PartyName No 1 1 A ASHWINI VINOD VAIRAGAR SC (W) Elephant Bahujan Samaj Party 2 1 A KIRAN NILESH JATHAR SC (W) Lotus Bhartiya Janata Party 3 1 A Sonali Raju Thombare SC (W) Coconut Independent/Other 4 1 A Renuka Hulgesh Chalwadi SC (W) Hand Indian National Congress 5 1 A Vidya Anil Lokhande SC (W) Candles Republican Party of India (A) 6 1 A Vidya Ashok Patil SC (W) Cup and Saucer Bharip Bahujan Mahasangh 7 1 A Chhaya Bhairavnath Ukarde SC (W) Railway Engine Maharashtra Navnirman Sena 8 1 A Kantabai Balasaheb Dhende SC (W) Whistle Bahujan Mukti Party 9 1 A AISHWARYA ASHUTOSH JADHAV SC (W) Clock Nationalist Congress Party 10 1 A Sushma Rahul Bengle SC (W) Television Independent/Other 11 1 A ARTI VIJAY KHARAT SC (W) Table Lamp Independent/Other 12 1 A SUNITA DILIP ORAPE SC (W) Jug Independent/Other 13 1 A NALINI RAJENDRA KAMBALE SC (W) Black Board Independent/Other 14 1 B NAVANATH SHIVAJI BHALCHIM ST Table Independent/Other 15 1 B Vithhal Ramchandra Kothere ST Clock Nationalist Congress Party 16 1 B Dunda Dongaru Kolap ST Bow And Arrow Shivsena 17 1 B Maruti Palhu Sangade ST Lotus Bhartiya Janata Party 18 1 C Menka Jitendra Karalekar BCC (W) Elephant Bahujan Samaj Party 19 1 C Alka Avinash Khade BCC (W) Lotus Bhartiya Janata Party 20 1 C MADHURI DASHRATH MATWANKAR BCC (W) Ring Independent/Other 21 1 C Hemlata Suryakant Pawaar BCC (W) Glass Tumbler Independent/Other 22 1 C रेखा चंकांत टंगरे BCC (W) Clock Nationalist Congress Party 23 1 C GULSHAN KARIM MULANI BCC (W) -

Communalisation of Education Delhi Historians' Group

Communalisation of Education The History Textbooks Controversy Delhi Historians’ Group CONTENTS Section 1 An Overview Communalisation of Education, The History Textbooks Controversy: An Overview Mridula Mukherjee and Aditya Mukherjee Section 2 What Historians Say 1. Propaganda as History won’t sell Romila Thapar 2. Historical Blunders Bipan Chandra 3. The Rewriting of History by the Sangh Parivar Irfan Habib 4. Communalism and History Textbooks R. S. Sharma 5. Guru Tegh Bahadur’s Martyrdom Satish Chandra 6. NCERT, ‘National Curriculum’ and ‘Destruction of History’ Arjun Dev 7. Does Indian History need to be re-written Sumit Sarkar Section 3 What other Commentators Say 1. Talibanasing Our Education Vir Sanghvi 2. Udder Complexity Dileep Padgaonkar 3. Textbooks and Communalism Rajeev Dhavan 4. Consensus be Damned Anil Bordia 5. What is History Subir Roy 6. History as Told by Non-Historians Anjali Modi 7. History,Vaccum-Cleaned Saba Naqvi Bhaumik 8. Joshi’s History Editorial in Indian Express 9. History as Nonsense Editorial in Indian Express Section 4 Text of the Deletions made from the NCERT books Section 1: An Overview COMMUNALISATION OF EDUCATION THE HISTORY TEXTBOOK CONTROVERSY: AN OVERVIEW Mridula Mukherjee and Aditya Mukherjee Professors of History Centre for Historical Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University The current controversy over the nature of history textbooks to be prescribed in schools reflects two completely divergent views of the Indian nation. One of the most important achievements of the Indian national movement, perhaps the greatest mass movement in world history, was the creation of the vision of an open, democratic, secular and civil libertarian state which was to promote a modern scientific outlook in civil society in independent India. -

Proposed Ban on Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd's Books in DU Raises

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Proposed Ban on Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd’s Books in DU Raises Questions about the Future of Critical Thought ANNA JACOB Anna Jacob ([email protected]) is a PhD scholar at the Department of History, University of Delhi. Vol. 53, Issue No. 47, 01 Dec, 2018 Scholars of social sciences write and teach from particular ideological and political frameworks, and to expect them to be “objective” or “non-partisan,” without any sensitivity to questions of power, takes away much needed perspectives of the marginalised sections of society in academia. Any critique of an academic work should stem not from unwillingness to deal with complex or discomfiting ideas, but from close reading and engagement. This article discusses these aspects in light of the recent call to ban Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd’s books from the University of Delhi’s MA Political Science reading list, as well as other instances of such interference in university curriculum in recent years. On 24 October 2018, the Standing Committee on Academic Affairs of the University of Delhi (DU) proposed a ban on three books authored by Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd—Why I Am Not a Hindu: A Sudra Critique of Hindutva Philosophy, Culture and Political Economy; God as Political Philosopher: Buddha’s Challenge to Brahmanism; and Post Hindu India—from the MA syllabus of the Department of Political Science. These texts are part of two courses titled “Dalit Bahujan Political Thought” and “Social Exclusion: Theory and Practice” (Roy Chowdhury 2018). The academic council is yet to take a final decision on the issue, but the department has decided to continue teaching the course. -

The Story of My Sanskrit - the Hindu 16/08/14 7:58 Am

The story of my Sanskrit - The Hindu 16/08/14 7:58 am Opinion » Lead The story of my Sanskrit Ananya Vajpeyi Sanskrit must be taken back from the clutches of Hindu supremacists, bigots, believers in brahmin exclusivity, misogynists, Islamophobes and a variety of other wrong-headed characters on the right, whose colossal ambition to control India’s vast intellectual legacy is only matched by their abysmal ignorance of what it means and how it works An article in this paper on July 30 revealed that Dina Nath Batra, head of the Shiksha Bachao Andolan Samiti, had formed a “Non-Governmental Education Commission” (NGEC) to recommend ways to “Indianise” education. I had encountered Mr. Batra’s notions about education during a campaign I was involved with in February and March this year, to keep the American scholar Wendy Doniger’s books about Hindus and Hinduism in print. His litigious threats had forced Penguin India to withdraw and destroy a volume by Prof. Doniger, and this was even before the national election installed the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as the ruling party in Delhi. Ever since Mr. Narendra Modi’s government has come to power, Mr. Batra has become more active, zealous and confrontational in stating his views about Indian history, Hindu religion, and what ought to qualify as appropriate content in schoolbooks and syllabi not only in his native Gujarat but in educational institutions all over the country. He is backed up by a vast governmental machinery, by the fact that Mr. Modi himself has penned prefatory materials to his various books, and of course by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), of which he has been a member and an ideologue for over several decades. -

100 Days Under the New Regime the State of Minorities 100 Days Under the New Regime the State of Minorities

100 Days Under the New Regime The State of Minorities 100 Days Under the New Regime The State of Minorities A Report Edited by John Dayal ISBN: 978-81-88833-35-1 Suggested Contribution : Rs 100 Published by Anhad INDIA HAS NO PLACE FOR HATE AND NEEDS NOT A TEN-YEAR MORATORIUM BUT AN END TO COMMUNAL AND TARGETTED VIOLENCE AGAINST RELIGIOUS MINORITIES A report on the ground situation since the results of the General Elections were announced on16th May 2014 NEW DELHI, September 27th, 2014 The Prime Minister, Mr. Narendra Modi, led by Bharatiya Janata Party to a resounding victory in the general elections of 2014, riding a wave generated by his promise of “development” and assisted by a remarkable mass mobilization in one of the most politically surcharged electoral campaigns in the history of Independent India. When the results were announced on 16th May 2014, the BJP had won 280 of the 542 seats, with no party getting even the statutory 10 per cent of the seats to claim the position of Leader of the Opposition. The days, weeks and months since the historic victory, and his assuming ofice on 26th May 2014 as the 14th Prime Minister of India, have seen the rising pitch of a crescendo of hate speech against Muslims and Christians. Their identity derided,their patriotism scoffed at, their citizenship questioned, their faith mocked. The environment has degenerated into one of coercion, divisiveness, and suspicion. This has percolated to the small towns and villages or rural India, severing bonds forged in a dialogue of life over the centuries, shattering the harmony build around the messages of peace and brotherhood given us by the Suis and the men and women who led the Freedom Struggle under Mahatma Gandhi. -

Infringement of Academic Freedom in India

H-Asia Infringement of Academic Freedom in India Discussion published by PROJIT B MUKHARJI on Wednesday, June 18, 2014 Dear Colleagues, I am writing to draw your attention to a new attack upon academic freedom in India. Dinanath Batra, an RSS activist, fresh from his success at getting Wendy Doniger’s book removed from Indian bookshops, has now turned his attention to Sekhar Bandyopadhyay’s excellent textbook on modern South Asian history, From Plassey to Partition. You can follow the developments at any of the following links:- http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/another-publisher-forced-to-censor-textbooks/article6075864 .ece?homepage=true http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/36024216.cms?intenttarget=no http://www.firstpost.com/living/children-of-marx-macaulay-are-defaming-hinduism-dinanath-batra-155 9083.html Besides issuing legal notices and initiating “civil and criminal proceedings”, an editorial in the RSS mouthpiece, The Organizer, also mentioned that Mr Batra would begin “an agitation against the book” unless the passages he objected to were removed from the BA 3rd Year History syllabus. Here is the link to the piece in The Organizer:- http://organiser.org/Encyc/2014/4/19/Legal-notice-to-Orient-Black-Swan-for-spreading-canard-against -RSS.aspx?NB&lang=3&m1&m2&p1&p2&p3&p4 In this regard, its worth pointing out that whilst Mr Batra's supporters insist that by following legal options of dissent he is himself excercising his democratic rights, the threat of 'agitation', irrespective of the legal outcome, makes such claims ring hollow. Moreover, what we are seeing in each case is that publishers--fearing perhaps both the 'agitation' and the protracted legal costs--are choosing to settle out of court. -

THURSDAY,THE 08Th NOVEMBER,2012

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR THURSDAY,THE 08th NOVEMBER,2012 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 1 TO 48 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 49 TO 50 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 51 TO 60 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 61 TO 82 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 08.11.2012 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 08.11.2012 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE RAJIV SAHAI ENDLAW [NOTE-I COUNSELS ARE REQUESTED TO PAGINATE THEIR FILES IN CONFIRMITY WITH THE COURT FILE IN ADVANCE.] [NOTE-II COUNSELS ARE REQUESTED TO PROVIDE LIST OF BOOKS / ACTS ON WHICH THEY ARE RELYING IN ADVANCE.] AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS 1. LPA 337/2010 VIJAY KUMAR SANJEEV MAHAJAN,MANOJ K CM APPL. 18344/2012 Vs. NEW DELHI MUNICIPAL SINGH,MANU NAYAR COUNCIL 2. W.P.(C) 195/2010 RAHUL MEHRA RAHUL MEHRA,DEVVRAT,PRASHANT CM APPL. 374/2010 Vs. UNION OF INDIA AND ORS BHUSHAN,SD SALWAN,DEVVRAT CM APPL. 972/2010 LOVKESH SAWHNEY,KK CM APPL. 2134/2011 KHURANA,NEERAJ CM APPL. 5253/2012 CHOUDHARY,ADITYA GARG,MANISH CM APPL. 8791/2012 RAGHAV,SHYEL TREHAN,SUSHIL CM APPL. 16396/2012 DUTT SALWAN 3. W.P.(C) 651/2012 DINANATH BATRA AND ORS MONIKA ARORA,NARESH KAUSHIK Vs. UOI AND ANR 4. W.P.(C) 2310/2012 INDIAN OLYMPIC ASSOCIATION LOVKESH SAWHNEY,RAHUL MEHRA CM APPL. 4946/2012 Vs. UNION OF INDIA CM APPL. -

Saffronisation of Education (December, 2014)

RGICS RAJIV GANDHI INSTITUTE FOR CONTEMPORARY STUDIES JAWAHAR BHAWAN, DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD ROAD, NEW DELHI-110001 Saffronisation of Education (December, 2014) RGICS brief Saffronisation of Education 2 Introduction Prof. Romila Thapar (Third Nikhil Chakravarti Memorial lecture delivered on 26 October 2014) said, ―The ultimate success of a democracy requires that the society be secular. By this I mean a society that goes beyond the co-existence of all religions; a society whose members have equal social and economic rights as citizens, and can exercise these rights irrespective of their religion; a society that is free from control by religious organisations in the activities related to these rights; a society where there is freedom to belong to any or no religion. Public intellectuals would be involved in explaining where secularisation lies and why it is inevitable in a democracy and in defending the secularising process.‖ Education being used a tool for ideological indoctrination of future generations. Concerted efforts are being made to target young minds are being targeted through school curricula and content of books. Rajnath Singh, ―It has been proposed that school textbooks be changed in order to ensure that children be made aware of human values and life values .‖( July 23,2014, Rajya Sabha).In the past 6 months several developments have taken place in the education sector which need to be examined without delay. It is becoming increasingly clear that the RSS agenda of pushing forward the Hindutva agenda in educational institutes starting from schools to universities has gained momentum. It is time for academicians, policy makers and activists to take cognizance of these changes taking place and speaking out against the agenda to impose ideas based on a particular religion.