Astudy on the Incapacitation Mechanism Model of the Juchist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moral Minority: the Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism

MORAL MINORITY POLITICS AND CULTURE IN MODERN AMERICA Series Editors Margot Canaday, Glenda Gilmore, Michael Kazin, and Thomas J. Sugrue Volumes in the series narrate and analyze po liti cal and social change in the broadest dimensions from 1865 to the present, including ideas about the ways people have sought and wielded power in the public sphere and the language and institutions of politics at all levels— local, national, and transnational. The series is motivated by a desire to reverse the fragmentation of modern U.S. history and to encourage synthetic perspectives on social movements and the state, on gender, race, and labor, and on intellectual history and pop u lar culture. MORAL MINORITY THE EVANGELICAL LEFT IN AN AGE OF CONSERVATISM DAVID R. SWARTZ UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS PHILADELPHIA Copyright © 2012 University of Pennsylvania Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104- 4112 www .upenn .edu/ pennpress Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Swartz, David R. Moral minority : the evangelical left in an age of conservatism / David R. Swartz. — 1st ed. p. cm. — (Politics and culture in modern America) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 8122- 4441- 0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Evangelicalism—United States—History—20th century. 2. -

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

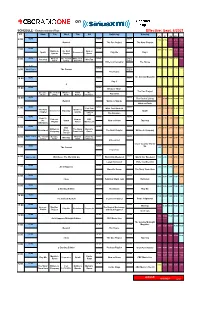

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

Georgetown University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics

INSTANT MESSAGING IN KOREAN FAMILIES: CREATING FAMILY THROUGH THE INTERPLAY OF PHOTOS, VIDEOS, AND TEXT A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics By Hanwool Choe, M.A. Washington, D.C. February 27, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Hanwool Choe All Rights Reserved ii INSTANT MESSAGING IN KOREAN FAMILIES: CREATING FAMILY THROUGH THE INTERPLAY OF PHOTOS, VIDEOS, AND TEXT Hanwool Choe, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Cynthia Gordon, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Extending previous research on family interaction (e.g., Tannen, Kendall, and Gordon 2007; Gordon 2009) and online multimodal discourse (e.g., Gordon forthcoming), I use interactional sociolinguistics to analyze instant messages exchanged among members of Korean families(-in-law). I explore how family talk is formulated and fostered online through technological affordances and multimodalities. Data are drawn from 5 chatrooms of 5 Korean families(-in-law), or 17 adult participants, on KakaoTalk, an instant messaging application popular in South Korea. In their instant messaging, family members accomplish meaning-making through actions and interactions, between online and offline, and with visuals and texts. This analysis employs the notion of "entextualization" (Bauman and Briggs 1990; Jones 2009), or the process of extracting and relocating (a part of) discourse, actions, materials, and media into a new context. I suggest that this meaning-making process -

Family, Mobile Phones, and Money: Contemporary Practices of Unification on the Korean Peninsula Sandra Fahy 82 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies

81 Family, Mobile Phones, and Money: Contemporary Practices of Unification on the Korean Peninsula Sandra Fahy 82 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies Moving from the powerful and abstract construct of ethnic homogeneity as bearing the promise for unification, this chapter instead considers family unity, facilitated by the quotidian and ubiquitous tools of mobile phones and money, as a force with a demonstrated record showing contemporary practices of unification on the peninsula. From the “small unification” (jageun tongil) where North Korean defectors pay brokers to bring family out, to the transmission of voice through the technology of mobile phones illegally smuggled from China, this paper explores practices of unification presently manifesting on the Korean Peninsula. National identity on both sides of the peninsula is usually linked with ethnic homogeneity, the ultimate idea of Koreanness present in both Koreas and throughout Korean history. Ethnic homogeneity is linked with nationalism, and while it is evoked as the rationale for unification it has not had that result, and did not prevent the ideological nationalism that divided the ethnos in the Korean War.1 The construction of ethnic homogeneity evokes the idea that all Koreans are one brethren (dongpo)—an image of one large, genetically related extended family. However, fissures in this ideal highlight the strength of genetic family ties.2 Moving from the powerful and abstract construct of ethnic homogeneity as bearing the promise for unification, this chapter instead considers family unity, facilitated by the quotidian and ubiquitous tools of mobile phones and money, as a force with a demonstrated record showing “acts of unification” on the peninsula. -

Effective Evangelistic Strategies for North Korean Defectors (Talbukmin) in South Korea

ABSTRACT Effective Evangelistic Strategies for North Korean Defectors (Talbukmin) in South Korea South Korean churches eagerness for spreading the gospel to North Koreans is a passion. However, because of the barriers between the two Koreas, spreading the Good News is nearly impossible. In the middle of the 1990’s, numerous North Koreans defected to China to avoid starvation. Many South Korean missionaries met North Koreans directly and offered the gospel along with necessities for survival in China. Since the early of 2000’s, many Talbukmin have entered South Korea so South Korean churches have directly met North Koreans and spread the gospel. However, the fruits of evangelism are few. South Korean churches find that Talbukmin are very different from South Koreans in large part due to the sixty-year division. South Korean churches do not know or fully understand the characteristics of the Talbukmin. The evangelism strategies and ministry programs of South Korean churches, which are designed for South Koreans, do not adapt well to serve the Talbukmin. This research lists and describes the following five theories to be used in the development of the effective evangelistic strategies for use with the Talbukmin and for use to interpret the interviews and questionnaires: the conversion theory, the contextualization theory, the homogenous principle, the worldview transformation theory, and the Nevius Mission Plan. In the following research exploration of the evangelization of Talbukmin in South Korea occurs through two major research agendas. The first agenda is concerned with the study of the characteristics of Talbukmin to be used for the evangelists’ understanding of the depth of differences. -

Thank You, Father Kim Il Sung” Is the First Phrase North Korean Parents Are Instructed to Teach to Their Children

“THANK YOU FATHER KIM ILLL SUNG”:”:”: Eyewitness Accounts of Severe Violations of Freedom of Thought, Conscience, and Religion in North Korea PPPREPARED BYYY: DAVID HAWK Cover Photo by CNN NOVEMBER 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Michael Cromartie Chair Felice D. Gaer Vice Chair Nina Shea Vice Chair Preeta D. Bansal Archbishop Charles J. Chaput Khaled Abou El Fadl Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Bishop Ricardo Ramirez Ambassador John V. Hanford, III, ex officio Joseph R. Crapa Executive Diretor NORTH KOREA STUDY TEAM David Hawk Author and Lead Researcher Jae Chun Won Research Manager Byoung Lo (Philo) Kim Research Advisor United States Commission on International Religious Freedom Staff Tad Stahnke, Deputy Director for Policy David Dettoni, Deputy Director for Outreach Anne Johnson, Director of Communications Christy Klaasen, Director of Government Affairs Carmelita Hines, Director of Administration Patricia Carley, Associate Director for Policy Mark Hetfield, Director, International Refugee Issues Eileen Sullivan, Deputy Director for Communications Dwight Bashir, Senior Policy Analyst Robert C. Blitt, Legal Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Scott Flipse, Senior Policy Analyst Mindy Larmore, Policy Analyst Jacquelin Mitchell, Executive Assistant Tina Ramirez, Research Assistant Allison Salyer, Government Affairs Assistant Stephen R. Snow, Senior Policy Analyst Acknowledgements The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom expresses its deep gratitude to the former North Koreans now residing in South Korea who took the time to relay to the Commission their perspectives on the situation in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and their experiences in North Korea prior to fleeing to China. -

Appendix 6 Board of Directors’ Response to the Recommendations Presented in the Ombudsmens’ Report

APPENDIX 6 BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ RESPONSE TO THE RECOMMENDATIONS PRESENTED IN THE OMBUDSMENS’ REPORT BOARD OF DIRECTORS of the CANADIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION STANDING COMMITTEES ON ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANGUAGE BROADCASTING Minutes of the Meeting held on June 18, 2014 Ottawa, Ontario = by videoconference Members of the Committee present: Rémi Racine, Chairperson of the Committees Hubert T. Lacroix Edward Boyd Peter Charbonneau George Cooper Pierre Gingras Marni Larkin Terrence Leier Maureen McCaw Brian Mitchell Marlie Oden Members of the Committee absent: Cecil Hawkins In attendance: Maryse Bertrand, Vice-President, Real Estate, Legal Services and General Counsel Heather Conway, Executive Vice-President, English Services () Louis Lalande, Executive Vice-President, French Services () Michel Cormier, Executive Director, News and Current Affairs, French Services () Stéphanie Duquette, Chief of Staff to the President and CEO Esther Enkin, Ombudsman, English Services () Tranquillo Marrocco, Associate Corporate Secretary Jennifer McGuire, General Manage and Editor in Chief, CBC News and Centres, English Services () Pierre Tourangeau, Ombudsman, French Services () Opening of the Meeting At 1:10 p.m., the Chairperson called the meeting to order. 2014-06-18 Broadcasting Committees Page 1 of 2 1. 2013-2014 Annual Report of the English Services’ Ombudsman Esther Enkin provided an overview of the number of complaints received during the fiscal year and the key subject matters raised, which included the controversy about paid speaking engagements by CBC personalities, the reporting on results polls, the style of, and views expressed by, a commentator, questions relating to matters of taste, the coverage regarding the mayor of Toronto, and the website’s section for comments. She also addressed the manner in which non-news and current affairs complaints are being handled by the Corporation. -

Book Review of "Nothing to Envy," by Barbara Demick, and "The Cleanest Race," by B.R

Book review of "Nothing to Envy," by Barbara Demick, and "The Cleanest Race," by B.R. Myers By Stephen Kotkin Sunday, February 28, 2010 NOTHING TO ENVY Ordinary Lives in North Korea By Barbara Demick Spiegel & Grau. 314 pp. $26 THE CLEANEST RACE How North Koreans See Themselves -- and Why It Matters By B.R. Myers Melville House. 200 pp. $24.95 "If you look at satellite photographs of the Far East by night, you'll see a large splotch curiously lacking in light," writes Barbara Demick on the first page of "Nothing to Envy." "This area of darkness is the Democratic People's Republic of Korea." As a correspondent for the Los Angeles Times, Demick discovered that the country isn't illuminated any further by traveling there. So she decided to penetrate North Korea's closed society by interviewing the people who had gotten out, the defectors, with splendid results. Of the hundred North Koreans Demick says she interviewed in South Korea, we meet six: a young kindergarten teacher whose aspirations were blocked by her father's prewar origins in the South ("tainted blood"); a boy of impeccable background who made the leap to university in Pyongyang and whose impossible romance with the kindergarten teacher forms the book's heart; a middle-age factory worker who is a model communist, a mother of four and the book's soul; her daughter; an orphaned young man; and an idealistic female hospital doctor, who looked on helplessly as the young charges in her care died of hunger during the 1996-99 famine. -

Human Rights Without Frontiers International

Human Rights Without Frontiers Int’l: Willy Fautre By Willy Fautré Wednesday, 14 December 2011 Human Rights Without Frontiers Int’l Commemorating Human Rights Day 2011, Houses of Parliament London, 9 December 2011 Human rights in North Korea: An International Coalition To Stop Crimes Against Humanity Willy Fautré North Korea is ranked in every survey of freedom and human rights as the worst of the worst. An estimated 200,000 people are trapped in a brutal system of political prison camps akin to Hitler's concentration camps and Stalin's gulag. Slave labor, horrific torture and bestial living conditions are now well-documented in numerous reports by human rights organizations, through the testimonies of survivors of these camps who have escaped. Although there is still a shroud of mystery surrounding North Korea, the world can no longer claim ignorance as an excuse. Shocking accounts of the worst possible forms of torture have emerged from survivors of the gulags who have escaped. Lee Sung Ae told the British Parliament about how when she was jailed, all her finger-nails were pulled out, all her lower teeth destroyed, and prison guards poured water, mixed with chillies, up her nose. Jung Guang Il was subjected to "pigeon torture," with his hands cuffed and tied behind his back in an excruciating position. He said he felt as though his bones were breaking through his chest. All his teeth were broken during beatings and his weight fell from 75kg to 38kg. Kim Hye Sook spent 28 years in the gulag and was first jailed at the age of 13 because her grandfather had gone to South Korea. -

North Korea Country Report BTI 2008

BTI 2008 | North Korea Country Report Status Index 1-10 2.46 # 122 of 125 Democracy 1-10 2.70 # 120 of 125 Ä Market Economy 1-10 2.21 # 122 of 125 Ä Management Index 1-10 1.90 # 122 of 125 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2008. The BTI is a global ranking of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economic systems as well as the quality of political management in 125 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. The BTI is a joint project of the Bertelsmann Stiftung and the Center for Applied Policy Research (C•A•P) at Munich University. More on the BTI at http://www.bertelsmann-transformation-index.de/ Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2008 — North Korea Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2007. © 2007 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2008 | North Korea 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 22.5 HDI - GDP p.c. $ - Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.5 HDI rank of 177 - Gini Index - Life expectancy years 64 UN Education Index - Poverty3 % - Urban population % 61.6 Gender equality2 - Aid per capita $ 3.9 Sources: UNDP, Human Development Report 2006 | The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2007 | OECD Development Assistance Committee 2006. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate 1990-2005. (2) Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary On 9 October 2006, in defiance of international warnings, North Korea performed an underground nuclear test. This was seen as a major blow to global efforts aimed at curbing North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, and as an emphatic statement of its determination to use every available means in order to survive. -

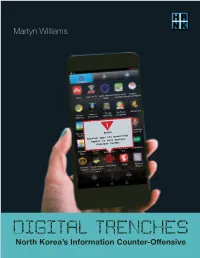

Digital Trenches

Martyn Williams H R N K Attack Mirae Wi-Fi Family Medicine Healthy Food Korean Basics Handbook Medicinal Recipes Picture Memory I Can Be My Travel Weather 2.0 Matching Competition Gifted Too Companion ! Agricultural Stone Magnolia Escpe from Mount Baekdu Weather Remover ERRORTelevision the Labyrinth Series 1.25 Foreign apps not permitted. Report to your nearest inminban leader. Business Number Practical App Store E-Bookstore Apps Tower Beauty Skills 2.0 Chosun Great Chosun Global News KCNA Battle of Cuisine Dictionary of Wisdom Terms DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive Copyright © 2019 Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior permission of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 435 Washington, DC 20036 P: (202) 499-7970 www.hrnk.org Print ISBN: 978-0-9995358-7-5 Digital ISBN: 978-0-9995358-8-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019919723 Cover translations by Julie Kim, HRNK Research Intern. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gordon Flake, Co-Chair Katrina Lantos Swett, Co-Chair John Despres,