A Flock of Doves: U.S. Women's Colleges and Their Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Are There Seven Sisters?

Why are there Seven Sisters? Ray P. Norris1,2 & Barnaby R. M. Norris3,4,5 1 Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith South, NSW 1797, Australia 2 CSIRO Astronomy & Space Science, PO Box 76, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia 3 Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics, Physics Road, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 4 Sydney Astrophotonic Instrumentation Laboratories, Physics Road, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 5 AAO-USyd, School of Physics, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Abstract of six stars arranged symmetrically around a seventh, and is There are two puzzles surrounding the therefore probably symbolic rather than a literal picture of Pleiades, or Seven Sisters. First, why are the Pleiades. the mythological stories surrounding them, In Greek mythology, the Seven Sisters are named after typically involving seven young girls be- the Pleiades, who were the daughters of Atlas and Pleione. ing chased by a man associated with the Their father, Atlas, was forced to hold up the sky, and was constellation Orion, so similar in vastly sep- therefore unable to protect his daughters. But to save them arated cultures, such as the Australian Abo- from being raped by Orion the hunter, Zeus transformed them riginal cultures and Greek mythology? Sec- into stars. Orion was the son of Poseidon, the King of the sea, ond, why do most cultures call them “Seven and a Cretan princess. Orion first appears in ancient Greek Sisters" even though most people with good calendars (e.g. Planeaux , 2006), but by the late eighth to eyesight see only six stars? Here we show that both these puzzles may be explained by early seventh centuries BC, he is said to be making unwanted a combination of the great antiquity of the advances on the Pleiades (Hesiod, Works and Days, 618-623). -

The Pleiades: the Celestial Herd of Ancient Timekeepers

The Pleiades: the celestial herd of ancient timekeepers. Amelia Sparavigna Dipartimento di Fisica, Politecnico di Torino C.so Duca degli Abruzzi 24, Torino, Italy Abstract In the ancient Egypt seven goddesses, represented by seven cows, composed the celestial herd that provides the nourishment to her worshippers. This herd is observed in the sky as a group of stars, the Pleiades, close to Aldebaran, the main star in the Taurus constellation. For many ancient populations, Pleiades were relevant stars and their rising was marked as a special time of the year. In this paper, we will discuss the presence of these stars in ancient cultures. Moreover, we will report some results of archeoastronomy on the role for timekeeping of these stars, results which show that for hunter-gatherers at Palaeolithic times, they were linked to the seasonal cycles of aurochs. 1. Introduction Archeoastronomy studies astronomical practices and related mythologies of the ancient cultures, to understand how past peoples observed and used the celestial phenomena and what was the role played by the sky in their cultures. This discipline is then a branch of the cultural astronomy, an interdisciplinary field that relates astronomical phenomena to current and ancient cultures. It must then be distinguished from the history of astronomy, because astronomy is a culturally specific concept and ancient peoples may have been related to the sky in different way [1,2]. Archeoastronomy is considered as a quite new interdisciplinary science, rooted in the Stonehenge studies of 1960s by the astronomer Gerald Hawkins, who tested Stonehenge alignments by computer, and concluded that these stones marked key dates in the megalithic calendar [3]. -

Seeking the Pleiades

Seeking the Pleiades By Irvin Owens Jr., Island City Lodge No. 215 Introduction As a child, I attended a Quaker school. As is typical with Quaker education, we spent a good amount of time learning to respect and understand the impacts that nature would have on us, as well as the impact that we could have on nature. My first experience with the Pleiades was when our science teacher brought an astronomer into our class who began telling us about the constellations. I was mesmerized as he began showing us those ancient twinkling orbs through his telescope. When he got to the Pleiades, I was captivated by the beauty of the six clustered blue stars, as well as the heart-wrenching story of their flight from the lecherous Orion. I failed to understand how things were better for the Pleiades after Zeus turned them into a flock of doves. As I became interested in Masonry and began to study the Entered Apprentice tracing board, I noticed that Jacob's ladder pointed to the Moon surrounded by the Pleiades in many depictions. This is a powerful and beautiful symbol, which is important to understand more deeply in order to truly appreciate the power of the first degree. Mythology Ancient Greece and Rome The Pleiades feature prominently in Greek literature, beginning with Homer’s second book of the Georgics of Hesiod. In this poem, he describes the Pleiades as an aid to understanding when to harvest: “When, Atlas’ birth, the Pleiades arise, Harvest begin, plow when they leave, the skies. Twice twenty days and nights these hide their heads; The year then turning, leave again their beds, And show when first to whet the harvest steel. -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

07-05-2020 Then I Made

Then I Made You Genesis 1:27-29 Wayne Eberly July 5, 2020 “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” Imagine reading the bible for the very first time. Imagine if this mystical and marvelous being known as God took you by the hand and guided you through the story of creation. “Come see what I made.” Oh, is it possible God was pleased with what he made? Is it possible that what God made was good? Maybe even very good? Oh yes, what God made is very good, and so imagine God taking your hand and guiding you through the majesty and the glory of God’s very good creation. “In the beginning God created the heavens…” Once God took a discouraged and disconsolate man named Job and used the heavens as a proving ground for just how good God is. “Can you bind Pleiades? Can you lose the cords of Orion? Can you bring forth the constellations in the seasons or lead out the Bear with her cubs?” (Job 38:31,32) The stars tell of the handiwork of God. Poor old Job just wanted some answers as to why his life was so miserable. Instead God said, “Look what I made.” As Job nodded his head absently, picking at his boils and distracted by the painful sores that covered his broken-down body, God waxed eloquent. “Pleiades…the Greeks said that magnificent cluster of stars were the seven daughters of the Titan Atlas and the Oceanid Pleione. They were pursued by the hunter Orion until Zeus changed them into a cluster of stars…and over there, that dominant constellation is Ursa Major, the Great Bear…ah, don’t mis the Milky Way…oh, and there is the Big Dipper. -

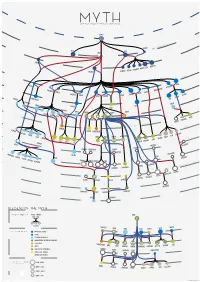

Legend of the Myth

MYTH Graph of greek mythological figures CHAOS s tie dei ial ord EREBUS rim p EROS NYX GAEA PONTU S ESIS NEM S CER S MORO THANATO A AETHER HEMER URANUS NS TA TI EA TH ON PERI IAPE HY TUS YNE EMNOS MN OC EMIS EANUS US TH TETHYS COE LENE PHOEBE SE EURYBIA DIONE IOS CREUS RHEA CRONOS HEL S EO PR NER OMETH EUS EUS ERSE THA P UMAS LETO DORIS PAL METIS LAS ERIS ST YX INACHU S S HADE MELIA POSEIDON ZEUS HESTIA HERA P SE LEIONE CE A G ELECTR CIR OD A STYX AE S & N SIPH ym p PA hs DEMETER RSES PE NS MP IA OLY WELVE S EON - T USE OD EKATH M D CHAR ON ARION CLYM PERSEPHONE IOPE NE CALL GALA CLIO TEA RODITE ALIA PROTO RES ATHENA APH IA TH AG HEBE A URAN AVE A DIKE MPHITRIT TEMIS E IRIS OLLO AR BIA AP NIKE US A IO S OEAGR ETHRA THESTIU ATLA S IUS ACRIS NE AGENOR TELEPHASSA CYRE REUS TYNDA T DA AM RITON LE PHEUS BROS OR IA E UDORA MAIA PH S YTO PHOEN OD ERYTHE IX EUROPA ROMULUS REMUS MIG A HESP D E ERIA EMENE NS & ALC UMA DANAE H HARMONIA DIOMEDES ASTOR US C MENELA N HELE ACLES US HER PERSE EMELE DRYOPE HERMES MINOS S E ERMION H DIONYSUS SYMAETHIS PAN ARIADNE ACIS LATRAMYS LEGEND OF THE MYTH ZEUS FAMILY IN THE MYTH FATHER MOTHER Zeus IS THEM CHILDREN DEMETER LETO HERA MAIA DIONE SEMELE COLORS IN THE MYTH PRIMORDIAL DEITIES TITANS SEA GODS AND NYMPHS DODEKATHEON, THE TWELVE OLYMPIANS DIKE OTHER GODS PERSEPHONE LO ARTEMIS HEBE ARES HERMES ATHENA APHRODITE DIONYSUS APOL MUSES EUROPA OSYNE GODS OF THE UNDERWORLD DANAE ALCEMENE LEDA MNEM ANIMALS AND HYBRIDS HUMANS AND DEMIGODS circles in the myth 196 M - 8690 K } {Google results M CALLIOPE INOS PERSEU THALIA CLIO 8690 K - 2740 K S HERACLES HELEN URANIA 2740 K - 1080 K 1080 K - 2410 J. -

Constellation Legends

Constellation Legends by Norm McCarter Naturalist and Astronomy Intern SCICON Andromeda – The Chained Lady Cassiopeia, Andromeda’s mother, boasted that she was the most beautiful woman in the world, even more beautiful than the gods. Poseidon, the brother of Zeus and the god of the seas, took great offense at this statement, for he had created the most beautiful beings ever in the form of his sea nymphs. In his anger, he created a great sea monster, Cetus (pictured as a whale) to ravage the seas and sea coast. Since Cassiopeia would not recant her claim of beauty, it was decreed that she must sacrifice her only daughter, the beautiful Andromeda, to this sea monster. So Andromeda was chained to a large rock projecting out into the sea and was left there to await the arrival of the great sea monster Cetus. As Cetus approached Andromeda, Perseus arrived (some say on the winged sandals given to him by Hermes). He had just killed the gorgon Medusa and was carrying her severed head in a special bag. When Perseus saw the beautiful maiden in distress, like a true champion he went to her aid. Facing the terrible sea monster, he drew the head of Medusa from the bag and held it so that the sea monster would see it. Immediately, the sea monster turned to stone. Perseus then freed the beautiful Andromeda and, claiming her as his bride, took her home with him as his queen to rule. Aquarius – The Water Bearer The name most often associated with the constellation Aquarius is that of Ganymede, son of Tros, King of Troy. -

Divine Riddles: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014

Divine Riddles: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014 E. Edward Garvin, Editor What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable). -

The Night Sky the Newsletter of the Astronomy Club of Akron

The Night Sky The Newsletter of The Astronomy Club of Akron www.acaoh.org Volume 35 Number 11 November 2013 Next Meeting: Friday - November 22, 2013 - 8:00 PM - Kiwanis The President’s Column By Gary Smith Hello to all fellow sky watchers and aficionados of the celestial sphere. November has always been challenged to give a special performance for residents of the northern latitudes. The temperature after sundown is a bit chilly and most of us have already searched the closets for our Winter clothes. Well, the November of 2013 will not disappoint. The very bright object in the southwest at sundown is the magnificent planet Venus. A combination of special circumstances allows Venus to reach a brightness of –4.6 magnitude. Venus has very thick clouds that are highly reflective of the sunlight. It has an average distance of The Helix Nebula (NGC 7293) by ACA Member Len Marek. Meade 14” 0.723 AU’s from the Sun. At close LX850 ACF and SBIG ST8300M. 6X5min Ha, OIII, SII (Hubble Palette). approach the Earth-Venus distance is only 26 million miles (0.28 AU’s). It is common for Venus to become appreciated by amateur astronomers The Andromeda Galaxy (M 31) bright enough to cast shadows in dark and planetary scientists and are still has already been discussed. But I areas on moonless nights. being studied today. would like to say the months of November and December have The King of the Planets, Jupiter Another reason for the importance performed well by raising M31 to our will make its appearance on the of Jupiter is that NASA mission observers meridian. -

Updated Peer-Review of the Wildlife Conservation Plan of the WII, Etalin Hydropower Project, Dibang, Arunachal Pradesh, 5 May 20

Peer-review of the Wildlife Conservation Plan, prepared by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) for the Etalin Hydropower Project, Dibang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh 5 May 2020 CONTRIBUTORS LISTED ALPHABETICALLY Anindya Sinha, PhD, National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru Anirban Datta Roy, PhD, Independent researcher Arjun Kamdar, National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bengaluru Aparajita Datta, PhD, Senior Scientist, Nature Conservation Foundation, Bengaluru Chihi Umbrey, MSc, Department of Zoology, Rajiv Gandhi University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh Chintan Sheth, MSc, Independent researcher M. Firoz Ahmed, PhD, Scientist F, Head, Herpetofauna Research and Conservation Division, Aaranyak, Guwahati Jagdish Krishnaswamy, PhD, Convenor and Senior Fellow, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, Bengaluru Jayanta Kumar Roy, PhD, Senior Researcher, Herpetofauna Research and Conservation Division, Aaranyak, Guwahati Karthik Teegalapalli, PhD, Independent researcher Khyanjeet Gogoi, TOSEHIM, Regional Orchids Germplasm Conservation and Propagation Centre, Assam Circle Krishnapriya Tamma, PhD, Azim Premji University, Bengaluru Manish Kumar, PhD, Fellow, Centre for Ecology Development and Research, Uttarakhand Megha Rao, MSc, Nature Conservation Foundation, Bengaluru Monsoonjyoti Gogoi, PhD, Scientist B, Bombay Natural History Society Narayan Sharma, PhD, Assistant Professor, Cotton University, Guwahati Neelesh Dahanukar, PhD, Scientist, Zoo Outreach Organization, Coimbatore Rajeev Raghavan, PhD, South Asia Coordinator, -

The Pleiades Star Cluster, in the Constellation of Orion, Is the Location of the 'Home World', and from Whence the Atlanteans Came

THE PLEIADES Compiled by Campbell M Gold (2008) CMG Archives http://campbellmgold.com --()-- Introduction In o.e.v lore, the Pleiades star cluster, in the constellation of Orion, is the location of the 'Home World', and from whence the Atlanteans came. Very faint echoes of the alternative history can be found in the mythology surrounding the Pleiades, especially regarding Merope. The Pleiades In mythology, the Pleiades were the seven daughters of the titan Atlas and the sea-nymph Pleione, and were born on Mount Cyllene. They are the siblingss of Calypso, Hyas, the Hyades, and the Hesperides. The Pleiades were nymphs in the train of Artemis, and together with the seven Hyades were called the Atlantides, Dodonides, or Nysiades, nursemaids and teachers to the infant Bacchus. The Seven Sisters 1) Maia , eldest of the seven Pleiades, was mother of Hermes by Zeus and Iris by Thaumas. 2) Electra was mother of Dardanus and Iasion by Zeus. 3) Taygete was mother of Lacedaemon, also by Zeus. 4) Alcyone was mother of Hyrieus by Poseidon. 5) Celaeno was mother of Lycus and Eurypylus by Poseidon. 6) Sterope (also Asterope) was mother of Oenomaus by Ares. 7) Merope , youngest of the seven Pleiades, was wooed by Orion. In other mythic contexts she married Sisyphus and, becoming mortal, she faded away. She bore to Sisyphus several sons. How Did The Seven Sisters Become Stars? The Seven Sisters received their "Catasterismi" (placement among the stars) when they all committed suicide because they were "so saddened" by either the fate of their father, Atlas, or the loss of their siblings, the Hyades (also daughters of Zeus). -

Bulfinch's Mythology the Age of Fable by Thomas Bulfinch

1 BULFINCH'S MYTHOLOGY THE AGE OF FABLE BY THOMAS BULFINCH Table of Contents PUBLISHERS' PREFACE ........................................................................................................................... 3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 7 ROMAN DIVINITIES ............................................................................................................................ 16 PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA ............................................................................................................ 18 APOLLO AND DAPHNE--PYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS ............................ 24 JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTO--DIANA AND ACTAEON--LATONA AND THE RUSTICS .................................................................................................................................................... 32 PHAETON .................................................................................................................................................. 41 MIDAS--BAUCIS AND PHILEMON ....................................................................................................... 48 PROSERPINE--GLAUCUS AND SCYLLA ............................................................................................. 53 PYGMALION--DRYOPE-VENUS