An Economic Analysis of Taxicab Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rules and Procedures

BOSTON POLICE DEPARTMENT RULES AND PROCEDURES Rule 403 October 30, 2015 HACKNEY CARRIAGE RULES AND REGULATIONS SECTION 1: OVERVIEW I. Definitions a. Boston Police Officer: An individual appointed by the Police Commissioner to carry out the functions of the Boston Police Department, including but not limited to, the preservation of the public peace, the protection of life and property, the prevention of crime, the arrest and prosecution of violators of the law, the proper enforcement of all laws and ordinances and the effective delivery of police services. b. Hackney Carriage: A vehicle used or designed to be used for the conveyance of persons for hire from place to place within the city of Boston, except a street or elevated railway car or a trackless trolley vehicle, within the meaning of Massachusetts General Laws chapter 163 section 2, or a motor vehicle, known as a jitney, operated in the manner and for the purposes set forth in Massachusetts General Laws chapter 159 A, or a sight-seeing automobile licensed under Chapter 399 of the Acts of 1931. Also known as a taxicab or taxi. c. Inspector of Carriages: A superior officer of the Boston Police Department assigned by the Police Commissioner to command the Hackney Carriage Unit. d. Licensed Hackney Driver: An individual, also referred to as a “Driver,” granted a license to operate a Hackney Carriage by the Police Commissioner. e. Medallion Owner: An individual, also referred to as an “Owner,” who has been deemed a suitable individual by the Police Commissioner to own a Hackney Carriage Medallion and who has purchased one or more such Medallions. -

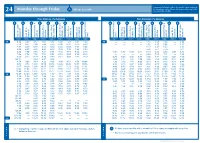

Monday Through Friday Mt

New printed schedules will not be issued if trips are adjusted Monday through Friday All trips accessible by five minutes or less. Please visit www.go-metro.com for the go smart... go METRO 24 most up-to-date schedule. 24 Mt. Lookout–Uptown–Anderson Riding Metro From Anderson / To Downtown From Downtown / To Anderson . 1 No food, beverages or smoking on Metro. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 2. Offer front seats to older adults and people with disabilities. METRO* PLUS 3. All Metro buses are 100% accessible for people 38X with disabilities. 46 UNIVERSITY OF 4. Use headphones with all audio equipment 51 CINCINNATI GOODMAN DANA MEDICAL CENTER HIGHLAND including cell phones. Anderson Center Station P&R Salem Rd. & Beacon St. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Liberty St. & Sycamore St. Square Government Area B Square Government Area B Liberty St. & Sycamore St. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly Salem Rd. & Beacon St. Anderson Center Station P&R 11 ZONE 2 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 2 43 5. Fold strollers and carts. BURNET MT. LOOKOUT AM AM 38X 4:38 4:49 4:57 5:05 5:11 5:20 5:29 5:35 5:40 — — — — 4:10 4:15 4:23 — 4:35 OBSERVATORY READING O’BRYONVILLE LINWOOD 6. -

The Effects of Fare-Collection Strategies on Transit Level of Service

Transportation Research Record 1036 79 The Effects of Fare-Collection Strategies on Transit Level of Service UPALI VANDEBONA and ANTHONY J. RICHARDSON ABSTRACT It is known that different fare-collection strategies have different passenger boarding and alighting rates for street-based public transport services. In this pape r, various models of stop service times are reviewed, the available empirical observations of boarding and alighting rates are summarized, and the effects of different average boarding rates and coefficients of variation of boarding rates on the route performance of a tram (light rail transit) service are examined. The analysis is conducted using the TRAMS (Transit Route Anima tion and Modeling by Simulation) package. This modeling package is briefly described with particular attention to the passenger demand subroutine as well as the tram stop service times subroutine. As a result o f the analysis , it was found that slower boarding rates produce a slower and less reliable service along the route. The variability of boarding rates has no effect on route travel time but does contribute to greater unreliability in level of service. It is concluded that these level-of-service effects need to be considered when assessing the effect of changes in fare-collection strategies. Public transport operators and managers have found systems to proof-of-payment systems will generally themselves under increasing pressure in recent years bring about significant level-of-service improve because of conflicting expectations from different ments that should be considered in any analysis of groups in the community. On the one hand, public such fare collection strategies. -

Reduced Cost Metro Transportation for People with Disabilities

REDUCED COST AND FREE METRO TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES Individual Day Supports are tailored services and supports that are provided to a person or a small group of no more than two (2) people, in the community. This service lends very well to the use of public transportation and associated travel training, allowing for active learning while exploring the community and its resources. While the set rate includes funding for transportation, it is important to be resourceful when possible, using available discount programs to make your funds go further. METRO TRANSIT ACCESSIBILITY CENTER The Metro Transit Accessibility Center (202)962-2700 located at Metro headquarters, 600 Fifth Street NW, Washington, DC 20001, offers the following services to people with disabilities: Information and application materials for the Reduced Fare (half fare) program for Metrobus and Metrorail Information and application materials for the MetroAccess paratransit service Consultations and functional assessments to determine eligibility for MetroAccess paratransit service Replacement ID cards for MetroAccess customers Support (by phone) for resetting your MetroAccess EZ-Pay or InstantAccess password The Transit Accessibility Center office hours are 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays, with the exception of Tuesdays with hours from 8 a.m. - 2:30 p.m. REDUCED FAIR PROGRAM Metro offers reduced fare for people with disabilities who require accessibility features to use public transportation and who have a valid Metro Disability ID. The Metro Disability ID card offers a discount of half the peak fare on Metrorail, and a reduced fare of for 90¢ cash, or 80¢ paying with a SmarTrip® card on regular Metrobus routes, and a discounted fare on other participating bus service providers. -

PATCO New Automated Fare Collection System, Smart Card Or Magnetic- Your Choice

PATCO New Automated Fare Collection System, Smart card or Magnetic- Your choice PATCO’s new fare collection system will feature the FREEDOM card, which will revolutionize how customers purchase their fares and travel on the PATCO system. The FREEDOM card is a smart card that will provide a high level of convenience and reliability to customers who use PATCO consistently. For customers who do not opt to use the FREEDOM card or who use PATCO infrequently, new magnetic tickets will be available. In PATCO’s current fare system, plastic tickets that use first generation magnetic technology are used. Although that technology was state of the art several decades ago, the technology is outdated and the tickets are prone to damage by devices commonly found in today’s environment. Unlike the current tickets, which are re-encoded numerous times for use after being captured by the fare gates, the new magnetic tickets will be paper tickets and will not be reused after capture. The new magnetic tickets can be purchased using either cash or coins. This means that customers choosing to purchase a ticket will not have to first stop at a change machine to convert their bills to coins. Both one- and two-ride tickets can be purchased from all new ticket vending machines located outside the fare gates. A customer wishing to purchase a magnetic ticket will simply select the prompt on the ticket vending machine screen for purchase of a ticket and then select the destination and whether a single ride or double ride ticket is desired. The ticket vending machine will list the price of the purchase. -

Renewal Licensing Division New Application for Taxicab/Limousine Owner’S License Replacement Provide Vin of Vehicle Being Removed for Replacement______

RENEWAL LICENSING DIVISION NEW APPLICATION FOR TAXICAB/LIMOUSINE OWNER’S LICENSE REPLACEMENT PROVIDE VIN OF VEHICLE BEING REMOVED FOR REPLACEMENT_____________________ A Taxicab/Limousine Owner’s License does not entitle owner to drive a vehicle without also obtaining a Taxicab/Limousine Driver’s License. This application MUST be filled out for each and every taxicab/limousine applied for: Date: __________________________________ Company Name/Owner: _________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address: _________________________________________________________________________________________, the undersigned, hereby applies to the Town of Dover for a license to operate a public taxicab/limousine as desired below within the Town of Dover. The following questions MUST be answered: Home Phone____________________________________ Are you legally eligible to work in the United States? YES NO Business Phone__________________________________ Residential Address:______________________________________________________ Fax No._________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ e-mail address: __________________________________ Attach identification of proof that you are at least 21 years of age. If partnership, the following questions MUST be answered: Give firm name: _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Office Location:_________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Effect of Fares on Transit Riding

Effect of Fares on Transit Riding JOHN F. CURTIN, Partner, Simpson & Curtin, Philadelphia • FARES are perhaps the most sensitive aspect of transit service-balancing uneasily between political pressures and the need for operating revenue. Political campaigns in major American cities have been won and lost over transit fare issues, and there is substantial evidence that patrons react to fare increases at the turnstiles as well as at the polls. The correlation of price increase with loss of transit riding has been well established. Most utility commissions use a variation of the "shrinkage formula" devised by our firm more than 20 years ago when pressures of inflation first became manifest in fare increase proposals by transit companies. But the corollary questions of price differential among competing transit services, and the effect of joint fares in coordinated transit operations, have not been so well explored. What is the "sub-modal split" of riding between surface and rapid transit connecting two points, when the fare is 15 cents on one and 25 cents on the other? How much added traffic is attracted to rapid transit when the feeder bus fare is dropped from 20cents to 10 cents? When feeder and trunk lines are separate operations, how should the feeder line discount in the combination fare be shared between them? These are fundamental questions of revenue and cost apportionment in developing coordination between surface and rapid transit systems. Auto travel switches freely between systems-from county roads to city streets to state highways-without motor ists' awareness; division of motor fuel revenues among these systems is accomplished by legislative standards with varying degrees of sophistication. -

Fare Policy Analysis for Public Transport: a Discrete‐Continuous Modeling Approach Using Panel Data

Fare Policy Analysis for Public Transport: A Discrete‐Continuous Modeling Approach Using Panel Data by Hazem Marwan Zureiqat B.A. in Economics Macalester College, 2006 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Transportation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2008 © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved Signature of Author ………………………………………………………………………… Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 16, 2008 Certified by ……………………………………………………………………...................... Nigel H. M. Wilson Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Director, Master of Science in Transportation Program Thesis Supervisor Accepted by …………………………………………………………………………………. Daniele Veneziano Chairman, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students 2 Fare Policy Analysis for Public Transport: A Discrete‐Continuous Modeling Approach Using Panel Data by Hazem Marwan Zureiqat Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 16, 2008, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Transportation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract In many large metropolitan areas, public transport is very heavily used, and ridership is approaching system capacity in the peak periods. This has caused a shift in attention by agency decision‐makers to strategies that can more effectively manage the demand for public transport, rather than simply increase overall demand. In other words, a need has arisen to understand not only why people use public transport as opposed to other modes but also how they use public transport, in terms of their ticket, mode, and time‐of‐day choices. To that end, fares become an increasingly important policy tool that can trigger certain behavioral changes among riders. -

Passenger and Vehicle Fare Information Surcharges Seattle/Bainbridge, Seattle/Bremerton, Edmonds/Kingston Fauntleroy/Vashon

19-08-0392 Printed in the USA on recycled/recyclable paper. recycled/recyclable on USA the in Printed Seattle/Bainbridge, Seattle/Bremerton, Fauntleroy/Vashon, Point Defiance/Tahlequah, Americans with Disabilities Edmonds/Kingston Southworth/Vashon Mukilteo/Clinton Act (ADA) and Title VI Notice Seattle, Washington 98121-3014 Washington Seattle, 2901 Third Avenue Suite 500 Suite Avenue Third 2901 Passenger Regular Fare 8.65 Passenger Regular Fare 5.65 Passenger Regular Fare 5.20 It is the Washington State Department of Washington State Ferries State Washington In vehicle or walk on Senior/Disability/Medicare Card Fare 4.30 In vehicle or walk on Senior/Disability/Medicare Card Fare 2.80 In vehicle or walk on Senior/Disability/Medicare Card Fare 2.60 Transportation’s policy to ensure that no Youth Fare 4.30 Youth Fare 2.80 Youth Fare 2.60 person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin, or sex, as provided by Title VI Wave2Go Multi-Ride Card 69.70 Wave2Go Multi-Ride Card 45.70 Wave2Go Multi-Ride Card 42.10 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or based on Monthly Ferry Pass 111.55 Monthly Ferry Pass 73.15 Monthly Ferry Pass 67.40 disability as provided by the Americans with Bicycle Surcharge Passenger Fare Plus 1.00 Bicycle Surcharge Passenger Fare Plus 1.00 Bicycle Surcharge Passenger Fare Plus 1.00 Disabilities Act, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise Small Vehicle & Driver Regular Fare 12.35 Peak Season 16.00 Small Vehicle & Driver Regular Fare 15.75 Peak Season 20.40 Small Vehicle & Driver Regular Fare 7.40 Peak Season 9.70 discriminated against under any of its federally @WSFerries funded programs and activities. -

Chapter 25 Vehicles for Hire

CHAPTER 25 VEHICLES FOR HIRE1 Art. I. In General, §§ 25-1. -- 25-15. Art. II. Taxicabs, § 25-16 -- 25-53. Div. 1. Generally, §§ 25-16. -- 25-30. Div. 2. Business License, §§ 25-31. -- 25-45. Div. 3. Driver’s License, §§ 25-46. -- 25-53. ARTICLE I. IN GENERAL Secs. 25-1. -- 25-15. Reserved. ARTICLE II. TAXICABS DIVISION 1. GENERALLY Sec. 25-16. Definitions. The following words and phrases, when used in this article, shall have the meanings respectively ascribed to them: Motor Vehicle for Hire. The term “motor vehicle for hire” shall mean a motor vehicle not equipped with a taximeter designed to carry seven (7) or less persons for public hire at an hourly rate. Taxicab. The word “taxicab” shall mean a motor vehicle for transportation of seven (7) or less persons for hire upon a trip or mileage basis. (Code 1957, § 7.131) Cross reference - Definitions and rules of construction generally, §§ 1-2. Sec. 25-17. Lost Articles. Every taxicab driver, immediately after the termination of any hiring or employment, shall carefully search such taxicab for any property lost or left therein, and any such property unless sooner claimed or delivered to the owner shall be taken to the headquarters of the Police Department and deposited with the officer in charge within twenty-four (24) hours after the finding of such article. (Code 1957, § 7.147) 1 Cross reference – Traffic and motor vehicles, Ch. 22. 25-1 Detroit_906167_1 Sec. 25-18. Passengers. Every taxicab driver shall have the right to demand payment of the legal fare in advance, and may refuse employment until so prepaid, but no taxicab driver shall otherwise refuse or neglect to convey any orderly person upon request anywhere in the City unless previously engaged or unable to do so. -

Full Free Fare Public Transport: Objectives and Alternatives September | 2020

POLICY BRIEF FULL FREE FARE PUBLIC TRANSPORT: OBJECTIVES AND ALTERNATIVES SEPTEMBER | 2020 INTRODUCTION At a time when cities must prepare for and face serious services and infrastructure must remain the overarching environmental and societal challenges, sustainable principle throughout these discussions. It is therefore urban mobility has never been this high up on the crucial to carefully consider the stated objectives which agenda. With the transversal role that public transport this measure is meant to achieve as well as its impacts, in plays in terms of urban quality of life, increasing and order to decide whether or not it is the most appropriate facilitating its access is a major challenge. Following use of public funds. In doing so, one must keep in mind this line of thought, the concept of free fare public that free public transport as such does not exist, as transport (FFPT) has been gaining traction in the public transport service and infrastructure has to be funded discourse, as several large cities have been considering one way or another. Hence the reference to free fare this possibility. public transport means that public transport users do not contribute to funding the service directly through While free public transport is often brought up in the payment of a fare. political discussions, its implementation has very concrete implications on the organisation of public Drawing from the experience of FFPT cities, this Policy transport. Yet, the strengthening of public transport Brief provides an analysis of the various stated objectives and the extent to which FFPT is the right tool to achieve them. -

Transit Element to the Premium and Primary Transit Networks

Table of Contents I. Introduction …………………………………………………………………....1 II. Summary …………………………………………………………………….....3 III. Policies, Implementation Actions and Performance Measures……....6 IV. The Transit Network…………….….…………………………………...…18 o Characteristics of a Primary Transit Network o What Makes a Transit Network Function? o Networks, Key Characteristics, and Improvements o Implications of the Increase in Bus Service o Paratransit V. Planned Rail System Improvement……………………………….…...…...28 o Metrorail System Capacity Improvements o Northern Virginia High-Capacity Transit Improvements o Station Enhancements and Access Improvements VI. Program Implementation Strategies.……………………………………. 31 o Transit Development and Coordination Plan o Regional Coordination Appendix A: The Existing Transit System ……………………………………33 o Systems Managed by Arlington, WMATA or NVTC o Bus Facilities o Additional Public Transit o Private Commuter, Employee/Student, and Airport Service o Paratransit and Taxicab o Bikeshare o Department of Human Services and other Specialized Transportation I. Introduction The Master Transportation Plan (MTP) Goals and Policies document specifies three general policies that form the foundation of the MTP and, therefore, transportation in Arlington in the years ahead: integrating transportation with land use, supporting the design and operation of complete streets, and managing travel demand and transportation systems. Between 2015 and 2030, Arlington County population is projected to increase 25 percent and employment is projected to increase by 20 percent. Increasing and enhancing transit options is a prerequisite to accommodating continued long-term growth in Arlington’s population and business activity. As noted in the MTP, the integration of transit and land use, the organization of community development around high quality transit service, has been a foundational policy for the Metrorail corridors in the County for more than 30 years.