John Thomson Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explorer's Gazette

EEXXPPLLOORREERR’’SS GGAAZZEETTTTEE Published Quarterly in Pensacola, Florida USA for the Old Antarctic Explorers Association Uniting All OAEs in Perpetuating the Memory of United States Involvement in Antarctica Volume 18, Issue 4 Old Antarctic Explorers Association, Inc Oct-Dec 2018 Photo by Jack Green The first C-17 of the summer season delivers researchers and support staff to McMurdo Station after a two-week weather delay. Science Bouncing Back From A Delayed Start By Mike Lucibella The first flights from Christchurch to McMurdo were he first planes of the 2018-2019 Summer Season originally scheduled for 1 October, but throughout early Ttouched down at McMurdo Station’s Phoenix October, a series of low-pressure systems parked over the Airfield at 3 pm in the afternoon on 16 October after region and brought days of bad weather, blowing snow more than two weeks of weather delays, the longest and poor visibility. postponement of season-opening in recent memory. Jessie L. Crain, the Antarctic research support Delays of up to a few days are common for manager in the Office of Polar Programs at the National researchers and support staff flying to McMurdo Station, Science Foundation (NSF), said that it is too soon yet to Antarctica from Christchurch, New Zealand. However, a say definitively what the effects of the delay will be on fifteen-day flight hiatus is very unusual. the science program. Continued on page 4 E X P L O R E R ‘ S G A Z E T T E V O L U M E 18, I S S U E 4 O C T D E C 2 0 1 8 P R E S I D E N T ’ S C O R N E R Ed Hamblin—OAEA President TO ALL OAEs—I hope you all had a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year holiday. -

Endurance: a Glorious Failure – the Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914 – 16 by Alasdair Mcgregor

Endurance: A glorious failure – The Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914 – 16 By Alasdair McGregor ‘Better a live donkey than a dead lion’ was how Ernest Shackleton justified to his wife Emily the decision to turn back unrewarded from his attempt to reach the South Pole in January 1909. Shackleton and three starving, exhausted companions fell short of the greatest geographical prize of the era by just a hundred and sixty agonising kilometres, yet in defeat came a triumph of sorts. Shackleton’s embrace of failure in exchange for a chance at survival has rightly been viewed as one of the greatest, and wisest, leadership decisions in the history of exploration. Returning to England and a knighthood and fame, Shackleton was widely lauded for his achievement in almost reaching the pole, though to him such adulation only heightened his frustration. In late 1910 news broke that the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen would now vie with Shackleton’s archrival Robert Falcon Scott in the race to be first at the pole. But rather than risk wearing the ill-fitting and forever constricting suit of the also-ran, Sir Ernest Shackleton then upped the ante, and in March 1911 announced in the London press that the crossing of the entire Antarctic continent via the South Pole would thereafter be the ultimate exploratory prize. The following December Amundsen triumphed, and just three months later, Robert Falcon Scott perished; his own glorious failure neatly tailored for an empire on the brink of war and searching for a propaganda hero. The field was now open for Shackleton to hatch a plan, and in December 1913 the grandiloquently titled Imperial Transantarctic Expedition was announced to the world. -

Navigation on Shackleton's Voyage to Antarctica

Records of the Canterbury Museum, 2019 Vol. 33: 5–22 © Canterbury Museum 2019 5 Navigation on Shackleton’s voyage to Antarctica Lars Bergman1 and Robin G Stuart2 1Saltsjöbaden, Sweden 2Valhalla, New York, USA Email: [email protected] On 19 January 1915, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, under the leadership of Sir Ernest Shackleton, became trapped in their vessel Endurance in the ice pack of the Weddell Sea. The subsequent ordeal and efforts that lead to the successful rescue of all expedition members are the stuff of legend and have been extensively discussed elsewhere. Prior to that time, however, the voyage had proceeded relatively uneventfully and was dutifully recorded in Captain Frank Worsley’s log and work book. This provides a window into the navigational methods used in the day-to- day running of the ship by a master mariner under normal circumstances in the early twentieth century. The conclusions that can be gleaned from a careful inspection of the log book over this period are described here. Keywords: celestial navigation, dead reckoning, double altitudes, Ernest Shackleton, Frank Worsley, Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Mercator sailing, time sight Introduction On 8 August 1914, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic passage in the 22½ foot (6.9 m) James Caird to Expedition under the leadership of Sir Ernest seek rescue from South Georgia. It is ultimately Shackleton set sail aboard their vessel the steam a tribute to Shackleton’s leadership and Worsley’s yacht (S.Y.) Endurance from Plymouth, England, navigational skills that all survived their ordeal. with the goal of traversing the Antarctic Captain Frank Worsley’s original log books continent from the Weddell to Ross Seas. -

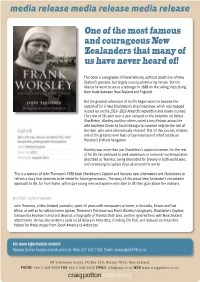

One of the Most Famous and Courageous New Zealanders That Many of Us Have Never Heard Of!

One of the most famous and courageous New Zealanders that many of us have never heard of! This book is a biography of Frank Worsley, without doubt one of New Zealand’s greatest, but largely unsung adventuring heroes. Born in Akaroa he went to sea as a teenager in 1888 on the sailing ships plying their trade between New Zealand and England. But the greatest adventure of his life began when he became the captain of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance, which was trapped in pack ice on the 1914–1916 Antarctic expedition and slowly crushed. The crew of 28 spent over a year camped on the Antarctic ice before Shackleton, Worsley and four others sailed a tiny lifeboat across the wild Southern Ocean to South Georgia to summon help for the rest of the men, who were all eventually rescued. This 17-day journey remains one of the greatest ever feats of seamanship and relied totally on Worsley’s brilliant navigation. Worsley was more than just Shackleton’s captain however. For the rest of his life he continued to seek adventures in a manner contemporaries described as ‘fearless’, being decorated for bravery in both world wars, and continuing to captain ships all around the world. This is a revision of John Thomson’s 1998 book Shackleton’s Captain and features new information and illustrations to refresh a story that deserves to be retold for future generations. The story of this proud New Zealander’s remarkable approach to life, far from home, will inspire young men and women who dare to lift their gaze above the ordinary. -

15-16 April No. 3

VOLUME 15-16 APRIL NO. 3 HONORARY PRESIDENT “BY AND FOR ALL ANTARCTICANS” Dr. Robert H. Rutford Post Office Box 325, Port Clyde, Maine 04855 PRESIDENT www.antarctican.org Dr. Anthony J. Gow www.facebook.com/antarcticansociety 117 Poverty Lane Lebanon, NH 03766 [email protected] Looking back .................................... 1 Stowaway in Antarctica ................... 9 VICE PRESIDENT First winter at 90 South ..................... 2 Ponies and dogs commemorated ….11 Liesl Schernthanner P.O. Box 3307 A teacher’s experience, 16 yrs later .. 4 Henry Worsley’s ending goal ......... 12 Ketchum, ID 83340 [email protected] Antarctic poem my heartfelt tribute .. 5 Correction: Jorgensen obituary ....... 12 TREASURER 1950s South Georgia Survey ............ 7 Gathering in Maine UPDATE! ... 12 Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple Box 325 Port Clyde, ME 04855 LOOKING BACK FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF TODAY Phone: (207) 372-6523 [email protected] Decades after returning to lives in lower latitudes, four veterans in this SECRETARY issue describe their Antarctic sojourns from a modern perspective. Cliff Joan Boothe o 2435 Divisadero Drive Dickey, near the end of that first winter at 90 S in 1957, “knew then that the San Francisco, CA 94115 United States would never leave the South Pole.” Teacher Joanna Hubbard, [email protected] 16 years after a season at Palmer Station, says the experience “likely set the WEBMASTER stage to keep me in education for the long haul.” Thomas Henderson Attorney Jim Porter, with 84 months on the Ice including four winters, 520 Normanskill Place Slingerlands, NY 12159 says, “I appreciate the inquiry about tying my Antarctic past to my federal [email protected] present, but it’s no use. -

After Editing

Shackleton Dates AUGUST 8th 1914 The team leave the UK on the ship, Endurance. DEC 5th 1914 They arrive at the edge of the Antarctic pack ice, in the Weddell Sea. JAN 18th 1915 Endurance becomes frozen in the pack ice. OCT 27TH 1915 Endurance is crushed in the ice after drifting for 9 months. Ship is abandoned and crew start to live on the pack ice. NOV 1915 Endurance sinks; men start to set up a camp on the ice. DEC 1915 The pack ice drifts slowly north; Patience camp is set up. MARCH 23rd 2016 They see land for the first time – 139 days have passed; the land can’t be reached though. APRIL 9th 2016 The pack ice starts to crack so the crew take to the lifeboats. APRIL 15th 1916 The 3 crews arrive on ELEPHANT ISLAND where they set up camp. APRIL 24th 1916 5 members of the team, including Shackleton, leave in the lifeboat James Caird, on an 800 mile journey to South Georgia, for help. MAY 10TH 1916 The James Caird crew arrive in the south of South Georgia. MAY 19TH -20TH Shackleton, Crean and Worsley walk across South Georgis to the whaling station at Stromness. MAY 23RD 1916 All the men on Elephant Island are safe; Shackleton starts on his first attempt at a rescue from South Georgia but ice prevents him. AUGUST 25th Shackleton leaves on his 4th attempt, on the Chilian tug boat Yelcho; he arrives on Elephant Island on August 30th and rescues all his crew. MAY 1917 All return to England. -

THE PUBLICATION of the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No

THE PUBLICATION OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 34, No. Vol 03 9 770003 532006 Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 Issue 237 Contents www.antarctic.org.nz is published quarterly by the New Zealand Antarctic Society Inc. ISSN 0003-5327 30 The New Zealand Antarctic Society is a Registered Charity CC27118 EDITOR: Lester Chaplow ASSISTANT EDITOR: Janet Bray New Zealand Antarctic Society PO Box 404, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand Email: [email protected] INDEXER: Mike Wing The deadlines for submissions to future issues are 1 November, 1 February, 1 May and 1 August. News 25 Shackleton’s Bad Lads 26 PATRON OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY: From Gateway City to Volunteer Duty at Scott Base 30 Professor Peter Barrett, 2008 NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY How You Can Help Us Save Sir Ed’s Antarctic Legacy 33 LIFE MEMBERS The Society recognises with life membership, First at Arrival Heights 34 those people who excel in furthering the aims and objectives of the Society or who have given outstanding service in Antarctica. They are Conservation Trophy 2016 36 elected by vote at the Annual General Meeting. The number of life members can be no more Auckland Branch Midwinter Celebration 37 than 15 at any one time. Current Life Members by the year elected: Wellington Branch – 2016 Midwinter Event 37 1. Jim Lowery (Wellington), 1982 2. Robin Ormerod (Wellington), 1996 3. Baden Norris (Canterbury), 2003 Travelling with the Huskies Through 4. Bill Cranfield (Canterbury), 2003 the Transantarctic Mountains 38 5. Randal Heke (Wellington), 2003 6. Bill Hopper (Wellington), 2004 Hillary’s TAE/IGY Hut: Calling all stories 40 7. -

JOURNAL Number Six

THE JAMES CAIRD SOCIETY JOURNAL Number Six Antarctic Exploration Sir Ernest Shackleton MARCH 2012 1 Shackleton and a friend (Oliver Locker Lampson) in Cromer, c.1910. Image courtesy of Cromer Museum. 2 The James Caird Society Journal – Number Six March 2012 The Centennial season has arrived. Having celebrated Shackleton’s British Antarctic (Nimrod) Expedition, courtesy of the ‘Matrix Shackleton Centenary Expedition’, in 2008/9, we now turn our attention to the events of 1910/12. This was a period when 3 very extraordinary and ambitious men (Amundsen, Scott and Mawson) headed south, to a mixture of acclaim and tragedy. A little later (in 2014) we will be celebrating Sir Ernest’s ‘crowning glory’ –the Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic (Endurance) Expedition 1914/17. Shackleton failed in his main objective (to be the first to cross from one side of Antarctica to the other). He even failed to commence his land journey from the Weddell Sea coast to Ross Island. However, the rescue of his entire team from the ice and extreme cold (made possible by the remarkable voyage of the James Caird and the first crossing of South Georgia’s interior) was a remarkable feat and is the reason why most of us revere our polar hero and choose to be members of this Society. For all the alleged shenanigans between Scott and Shackleton, it would be a travesty if ‘Number Six’ failed to honour Captain Scott’s remarkable achievements - in particular, the important geographical and scientific work carried out on the Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions (1901-3 and 1910-12 respectively). -

Whiteout: an Examination of the Material Culture of Remembrance and Identity Generated Between New Zealand and Antarctica Peter

Memory Connection Volume 1 Number 1 © 2011 The Memory Waka Whiteout: An Examination of the Material Culture of Remembrance and Identity Generated Between New Zealand and Antarctica Peter Wood Memory Connection Volume 1 Number 1 © 2011 The Memory Waka Whiteout: An Examination of the Material Culture of Remembrance and Identity Generated Between New Zealand and Antarctica Peter Wood Abstract This article examines the cultural artefacts of memory that have been produced as a result of New Zealand’s ongoing participation in the exploration of Antarctica. In this research I define two classes of Antarctic memory-making. The first is composed of geographically located artefacts directly associated with New Zealand’s physical participation in South Pole exploration. The second class posits representational interpretations of Antarctica as sites of cultural “meaningfulness” to New Zealand’s identity. Both categories are defined chronologically by the Antarctic Treaty (1959), which sought to protect objects of “historical interest” from damage or destruction while prohibiting the addition of other permanent artefacts. I suggest that one unforeseen outcome of the Antarctic Treaty was the creation of two states of memory: one of authentic history dating from before 1959, and another of documentary history (requiring representational interpretation), which has occurred since that time. The best examples of the former are the rudimentary huts which remain from the so-called “heroic period” of Antarctic exploration. An excellent example of the latter is found in the Artists to Antarctica programme in which selected New Zealand artists—writers, visual artists and musicians—have the opportunity to visit and record their views of the region’s unique qualities. -

Antarctica Glacier Navigate

In August 1914, as part of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Ernest Shackleton set off from Britain to Antarctica. The continent surrounding the Research Mrs Chippy—the ship’s cat. Ernest Shackleton wanted to be the first person to cross Antarctica by South Pole—almost entirely Antarctica What is the climate of Antarctica like? foot. covered by ice. Look up Shackleton’s journey on a map. Shackleton’s ship was called Endurance . an extremely large mass of ice Glacier which moves very slowly, In the freezing waters around Antarctica, the ship became trapped by the often down a mountain valley ice. The ice eventually crushed the ship meaning it had to be abandoned. Navigate To find a way to get to a place. Shackleton and his crew drifted on sheets of ice for months. Shackleton decided to use three lifeboats (rowing boats) through treacherous seas to reach Elephant Island—a bleak, ice-covered rock. Shackleton took five crew members with him in a small lifeboat to reach South Georgia (900 miles away) where they knew there was a whaling station. When they reached South Georgia, they had to hike 30 miles, climbing a mountain and crossing glaciers to reach the whaling station. A ship was then able to rescue the remaining 22 men on Elephant Island. Shackleton failed in his attempt to cross Antarctica by foot, but he became a hero for leading one of the greatest and bravest rescues in history. During another Antarctic mission in 1921, Shackleton fell ill and suffered a fatal heart attack, he died at the age of 47. -

SES Scientific Explorer Annual Review 2020.Pdf

SCIENTIFIC EXPLORER Dr Jane Goodall, Annual Review 2020 SES Lifetime Achievement 2020 (photo by Vincent Calmel) Welcome Scientific Exploration Society (SES) is a UK-based charity (No 267410) that was founded in 1969 by Colonel John Blashford-Snell and colleagues. It is the longest-running scientific exploration organisation in the world. Each year through its Explorer Awards programme, SES provides grants to individuals leading scientific expeditions that focus on discovery, research, and conservation in remote parts of the world, offering knowledge, education, and community aid. Members and friends enjoy charity events and regular Explorer Talks, and are also given opportunities to join exciting scientific expeditions. SES has an excellent Honorary Advisory Board consisting of famous explorers and naturalists including Sir Ranulph Fiennes, Dr Jane Goodall, Rosie Stancer, Pen Hadow, Bear Grylls, Mark Beaumont, Tim Peake, Steve Backshall, Vanessa O’Brien, and Levison Wood. Without its support, and that of its generous benefactors, members, trustees, volunteers, and part-time staff, SES would not achieve all that it does. DISCOVER RESEARCH CONSERVE Contents 2 Diary 2021 19 Vanessa O’Brien – Challenger Deep 4 Message from the Chairman 20 Books, Books, Books 5 Flying the Flag 22 News from our Community 6 Explorer Award Winners 2020 25 Support SES 8 Honorary Award Winners 2020 26 Obituaries 9 ‘Oscars of Exploration’ 2020 30 Medicine Chest Presentation Evening LIVE broadcast 32 Accounts and Notice of 2021 AGM 10 News from our Explorers 33 Charity Information 16 Top Tips from our Explorers “I am prepared to go anywhere, provided it be forward.” Mark Beaumont, SES Lifetime Achievement 2018 and David Livingstone SES Honorary Advisory Board member (photo by Ben Walton) SCIENTIFIC EXPLORER > 2020 Magazine 1 Please visit SES on EVENTBRITE for full details and tickets to ALL our events. -

Cape Denison MAWSON CENTENNIAL 1911–2011, Commonwealth Bay

Cape Denison MAWSON CENTENNIAL 1911–2011, Commonwealth Bay Mawson and the Australasian Geology of Cape Denison Landforms of Cape Denison Position of Cape Denison in Gondwana Antarctic Expedition The two dominant rock-types found at Cape Denison Cape Denison is a small ice-free rocky outcrop covering Around 270 Million years ago the continents that we are orthogneiss and amphibolite. There are also minor less than one square kilometre, which emerges from The Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) took place know today were part of a single ancient supercontinent occurrences of coarse grained felsic pegmatites. beneath the continental ice sheet. Stillwell (1918) reported between 1911 and 1914, and was organised and led by called Pangea. Later, Pangea split into two smaller that the continental ice sheet rises steeply behind Cape the geologist, Dr Douglas Mawson. The expedition was The Cape Denison Orthogneiss was described by Stillwell (1918) as supercontinents, Laurasia and Gondwana, and Denison reaching an altitude of ‘1000 ft in three miles and jointly funded by the Australian and British Governments coarse-grained grey quartz-feldspar layered granitic gneiss. These rock Antarctica formed part of Gondwana. with contributions received from various individuals and types are normally formed by metamorphism (changed by extreme heat 1500 ft in five and a half miles’ (approximately 300 metres and pressure) of granites. The Cape Denison Orthogneiss is found around In current reconstructions of the supercontinent Gondwana, the Cape scientific societies, including the Australasian Association to 450 metres over 8.9 kilometres). Photography by Chris Carson Cape Denison, the nearby offshore Mackellar Islands, and nearby outcrops Denison–Commonwealth Bay region was located adjacent to the coast for the Advancement of Science.