HUDSON, Huberht Taylor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explorer's Gazette

EEXXPPLLOORREERR’’SS GGAAZZEETTTTEE Published Quarterly in Pensacola, Florida USA for the Old Antarctic Explorers Association Uniting All OAEs in Perpetuating the Memory of United States Involvement in Antarctica Volume 18, Issue 4 Old Antarctic Explorers Association, Inc Oct-Dec 2018 Photo by Jack Green The first C-17 of the summer season delivers researchers and support staff to McMurdo Station after a two-week weather delay. Science Bouncing Back From A Delayed Start By Mike Lucibella The first flights from Christchurch to McMurdo were he first planes of the 2018-2019 Summer Season originally scheduled for 1 October, but throughout early Ttouched down at McMurdo Station’s Phoenix October, a series of low-pressure systems parked over the Airfield at 3 pm in the afternoon on 16 October after region and brought days of bad weather, blowing snow more than two weeks of weather delays, the longest and poor visibility. postponement of season-opening in recent memory. Jessie L. Crain, the Antarctic research support Delays of up to a few days are common for manager in the Office of Polar Programs at the National researchers and support staff flying to McMurdo Station, Science Foundation (NSF), said that it is too soon yet to Antarctica from Christchurch, New Zealand. However, a say definitively what the effects of the delay will be on fifteen-day flight hiatus is very unusual. the science program. Continued on page 4 E X P L O R E R ‘ S G A Z E T T E V O L U M E 18, I S S U E 4 O C T D E C 2 0 1 8 P R E S I D E N T ’ S C O R N E R Ed Hamblin—OAEA President TO ALL OAEs—I hope you all had a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year holiday. -

Endurance: a Glorious Failure – the Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914 – 16 by Alasdair Mcgregor

Endurance: A glorious failure – The Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914 – 16 By Alasdair McGregor ‘Better a live donkey than a dead lion’ was how Ernest Shackleton justified to his wife Emily the decision to turn back unrewarded from his attempt to reach the South Pole in January 1909. Shackleton and three starving, exhausted companions fell short of the greatest geographical prize of the era by just a hundred and sixty agonising kilometres, yet in defeat came a triumph of sorts. Shackleton’s embrace of failure in exchange for a chance at survival has rightly been viewed as one of the greatest, and wisest, leadership decisions in the history of exploration. Returning to England and a knighthood and fame, Shackleton was widely lauded for his achievement in almost reaching the pole, though to him such adulation only heightened his frustration. In late 1910 news broke that the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen would now vie with Shackleton’s archrival Robert Falcon Scott in the race to be first at the pole. But rather than risk wearing the ill-fitting and forever constricting suit of the also-ran, Sir Ernest Shackleton then upped the ante, and in March 1911 announced in the London press that the crossing of the entire Antarctic continent via the South Pole would thereafter be the ultimate exploratory prize. The following December Amundsen triumphed, and just three months later, Robert Falcon Scott perished; his own glorious failure neatly tailored for an empire on the brink of war and searching for a propaganda hero. The field was now open for Shackleton to hatch a plan, and in December 1913 the grandiloquently titled Imperial Transantarctic Expedition was announced to the world. -

Navigation on Shackleton's Voyage to Antarctica

Records of the Canterbury Museum, 2019 Vol. 33: 5–22 © Canterbury Museum 2019 5 Navigation on Shackleton’s voyage to Antarctica Lars Bergman1 and Robin G Stuart2 1Saltsjöbaden, Sweden 2Valhalla, New York, USA Email: [email protected] On 19 January 1915, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, under the leadership of Sir Ernest Shackleton, became trapped in their vessel Endurance in the ice pack of the Weddell Sea. The subsequent ordeal and efforts that lead to the successful rescue of all expedition members are the stuff of legend and have been extensively discussed elsewhere. Prior to that time, however, the voyage had proceeded relatively uneventfully and was dutifully recorded in Captain Frank Worsley’s log and work book. This provides a window into the navigational methods used in the day-to- day running of the ship by a master mariner under normal circumstances in the early twentieth century. The conclusions that can be gleaned from a careful inspection of the log book over this period are described here. Keywords: celestial navigation, dead reckoning, double altitudes, Ernest Shackleton, Frank Worsley, Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Mercator sailing, time sight Introduction On 8 August 1914, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic passage in the 22½ foot (6.9 m) James Caird to Expedition under the leadership of Sir Ernest seek rescue from South Georgia. It is ultimately Shackleton set sail aboard their vessel the steam a tribute to Shackleton’s leadership and Worsley’s yacht (S.Y.) Endurance from Plymouth, England, navigational skills that all survived their ordeal. with the goal of traversing the Antarctic Captain Frank Worsley’s original log books continent from the Weddell to Ross Seas. -

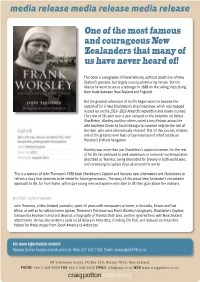

One of the Most Famous and Courageous New Zealanders That Many of Us Have Never Heard Of!

One of the most famous and courageous New Zealanders that many of us have never heard of! This book is a biography of Frank Worsley, without doubt one of New Zealand’s greatest, but largely unsung adventuring heroes. Born in Akaroa he went to sea as a teenager in 1888 on the sailing ships plying their trade between New Zealand and England. But the greatest adventure of his life began when he became the captain of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance, which was trapped in pack ice on the 1914–1916 Antarctic expedition and slowly crushed. The crew of 28 spent over a year camped on the Antarctic ice before Shackleton, Worsley and four others sailed a tiny lifeboat across the wild Southern Ocean to South Georgia to summon help for the rest of the men, who were all eventually rescued. This 17-day journey remains one of the greatest ever feats of seamanship and relied totally on Worsley’s brilliant navigation. Worsley was more than just Shackleton’s captain however. For the rest of his life he continued to seek adventures in a manner contemporaries described as ‘fearless’, being decorated for bravery in both world wars, and continuing to captain ships all around the world. This is a revision of John Thomson’s 1998 book Shackleton’s Captain and features new information and illustrations to refresh a story that deserves to be retold for future generations. The story of this proud New Zealander’s remarkable approach to life, far from home, will inspire young men and women who dare to lift their gaze above the ordinary. -

On Our Doorstep Parts 1 and 2

ON 0UR DOORSTEP I MEMORIAM THE SECOD WORLD WAR 1939 to 1945 HOW THOSE LIVIG I SOME OF THE PARISHES SOUTH OF COLCHESTER, WERE AFFECTED BY WORLD WAR 2 Compiled by E. J. Sparrow Page 1 of 156 ON 0UR DOORSTEP FOREWORD This is a sequel to the book “IF YOU SHED A TEAR” which dealt exclusively with the casualties in World War 1 from a dozen coastal villages on the orth Essex coast between the Colne and Blackwater. The villages involved are~: Abberton, Langenhoe, Fingringhoe, Rowhedge, Peldon: Little and Great Wigborough: Salcott: Tollesbury: Tolleshunt D’Arcy: Tolleshunt Knights and Tolleshunt Major This likewise is a community effort by the families, friends and neighbours of the Fallen so that they may be remembered. In this volume we cover men from the same villages in World War 2, who took up the challenge of this new threat .World War 2 was much closer to home. The German airfields were only 60 miles away and the villages were on the direct flight path to London. As a result our losses include a number of men, who did not serve in uniform but were at sea with the fishing fleet, or the Merchant avy. These men were lost with the vessels operating in what was known as “Bomb Alley” which also took a toll on the Royal avy’s patrol craft, who shepherded convoys up the east coast with its threats from: - mines, dive bombers, e- boats and destroyers. The book is broken into 4 sections dealing with: - The war at sea: the land warfare: the war in the air & on the Home Front THEY WILL OLY DIE IF THEY ARE FORGOTTE. -

Les Îles De La Manche ~ the Channel Islands

ROLL OF HONOUR 1 The Battle of Jutland Bank ~ 31st May 1916 Les Îles de la Manche ~ The Channel Islands In honour of our Thirty Six Channel Islanders of the Royal Navy “Blue Jackets” who gave their lives during the largest naval battle of the Great War 31st May 1916 to 1st June 1916. Supplement: Mark Bougourd ~ The Channel Islands Great War Study Group. Roll of Honour Battle of Jutland Les Îles de la Manche ~ The Channel Islands Charles Henry Bean 176620 (Portsmouth Division) Engine Room Artificer 3rd Class H.M.S. QUEEN MARY. Born at Vale, Guernsey 12 th March 1874 - K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 42) Wilfred Severin Bullimore 229615 (Portsmouth Division) Leading Seaman H.M.S. INVINCIBLE. Born at St. Sampson, Guernsey 30 th November 1887 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 28) Wilfred Douglas Cochrane 194404 (Portsmouth Division) Able Seaman H.M.S. BLACK PRINCE. Born at St. Peter Port, Guernsey 30 th September 1881 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 34) Henry Louis Cotillard K.20827 (Portsmouth Division) Stoker 1 st Class H.M.S. BLACK PRINCE. Born at Jersey, 2 nd April 1893 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 23) John Alexander de Caen 178605 (Portsmouth Division) Petty Officer 1 st Class H.M.S. INDEFATIGABLE. Born at St. Helier, Jersey 7th February 1879 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 37) The Channel Islands Great War Study Group. - 2 - Centenary ~ The Battle of Jutland Bank www.greatwarci.net © 2016 ~ Mark Bougourd Roll of Honour Battle of Jutland Les Îles de la Manche ~ The Channel Islands Stanley Nelson de Quetteville Royal Canadian Navy Lieutenant (Engineer) H.M.S. -

'The Admiralty War Staff and Its Influence on the Conduct of The

‘The Admiralty War Staff and its influence on the conduct of the naval between 1914 and 1918.’ Nicholas Duncan Black University College University of London. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005. UMI Number: U592637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592637 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS Page Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Chapter 1. 23 The Admiralty War Staff, 1912-1918. An analysis of the personnel. Chapter 2. 55 The establishment of the War Staff, and its work before the outbreak of war in August 1914. Chapter 3. 78 The Churchill-Battenberg Regime, August-October 1914. Chapter 4. 103 The Churchill-Fisher Regime, October 1914 - May 1915. Chapter 5. 130 The Balfour-Jackson Regime, May 1915 - November 1916. Figure 5.1: Range of battle outcomes based on differing uses of the 5BS and 3BCS 156 Chapter 6: 167 The Jellicoe Era, November 1916 - December 1917. Chapter 7. 206 The Geddes-Wemyss Regime, December 1917 - November 1918 Conclusion 226 Appendices 236 Appendix A. -

Sir Ernest Shackleton: Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

PRESS RELEASE S/49/05/16 South Georgia - Sir Ernest Shackleton: Centenary of The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, also known as the Endurance Expedition, is considered by some the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. By 1914 both Poles had been reached so Shackleton set his sights on being the first to traverse Antarctica. By the time of the expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton was already experienced in polar exploration. A young Lieutenant Shackleton from the merchant navy was chosen by Captain Scott to join him in his first bid for the South Pole in 1901. Shackleton later led his own attempt on the pole in the Nimrod expedition of 1908: he surpassed Scott’s southern record but took the courageous decision, given deteriorating health and shortage of provisions, to turn back with 100 miles to go. After the pole was claimed by Amundsen in 1911, Shackleton formulated a plan for a third expedition in which proposed to undertake “the largest and most striking of all journeys - the crossing of the Continent”. Having raised sufficient funds, he purchased a 300 tonne wooden barquentine which he named Endurance. He planned to take Endurance into the Weddell Sea, make his way to the South Pole and then to the Ross Sea via the Beardmore Glacier (to pick up supplies laid by a second vessel, Aurora, purchased from Sir Douglas Mawson). Although the expedition failed to accomplish its objective it became recognised instead as an epic feat of endurance. Endurance left Britain on 8 August 1914 heading first for Buenos Aires. -

Maltese Casualties in the Battle of Jutland - May 31- June 1, 1916

., ~ I\ ' ' "" ,, ~ ·r " ' •i · f.;IHJ'¥T\f 1l,.l~-!l1 MAY 26, 2019 I 55 5~ I MAY 26, 2019 THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA LIFE&WELLBEING HISTORY Maltese casualties in the Battle of Jutland - May 31- June 1, 1916 .. PATRICK FARRUGIA .... .. HMS Defence .. HMS lndefatigab!.e sinking HMS Black Prince ... In the afternoon and evening·of .. May 31, 1916, the Battle of Jutland (or Skagerrakschlact as it is krnwn •. to the Germans), was fought between the British Grand Fleet, under the command of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, and the German High Seas Fleet commanded by Admiral Reinhold Scheer. It was to be the largest nava~ bat tle and the only full.-scale clash between battleships of the war. The British Grand Fleet was com posed of 151 warships, among which were 28 bat:leships and nine battle cruisers, wiile the German High Seas Fleet consisted of 99 war ships, including 16 battleships and 54 battle cruisers. Contact between these mighty fleets was made shortly after 2pm, when HMS Galatea reported that she had sighted the enemy. The first British disaster occured at 4pm, when, while engaging SMS Von der Tann, HMS Indefatigable was hit by a salvo onherupperdeck. The amidships. A huge pillar of smoke baden when they soon came under Giovanni Consiglio, Nicolo FOndac Giuseppe Cuomo and Achille the wounded men was Spiro Borg, and 5,769 men killed, among them missiles apparently penetrated her ascended to the sky, and she sank attack of the approaching battle aro, Emmanuele Ligrestischiros, Polizzi, resi1ing in Valletta, also lost son of Lorenzo and Lorenza Borg 72 men with a Malta connection; 25 'X' magazine, for she was sudcenly bow first. -

Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance

9-803-127 REV: DECEMBER 2, 2010 NANCY F. KOEHN Leadership in Crisis: Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance For scientific discovery give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel give me Amundsen; but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton. — Sir Raymond Priestley, Antarctic Explorer and Geologist On January 18, 1915, the ship Endurance, carrying a highly celebrated British polar expedition, froze into the icy waters off the coast of Antarctica. The leader of the expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton, had planned to sail his boat to the coast through the Weddell Sea, which bounded Antarctica to the north, and then march a crew of six men, supported by dogs and sledges, to the Ross Sea on the opposite side of the continent (see Exhibit 1).1 Deep in the southern hemisphere, it was early in the summer, and the Endurance was within sight of land, so Shackleton still had reason to anticipate reaching shore. The ice, however, was unusually thick for the ship’s latitude, and an unexpected southern wind froze it solid around the ship. Within hours the Endurance was completely beset, a wooden island in a sea of ice. More than eight months later, the ice still held the vessel. Instead of melting and allowing the crew to proceed on its mission, the ice, moving with ocean currents, had carried the boat over 670 miles north.2 As it moved, the ice slowly began to soften, and the tremendous force of distant currents alternately broke apart the floes—wide plateaus made of thousands of tons of ice—and pressed them back together, creating rift lines with huge piles of broken ice slabs. -

Examined: Archaeological Investigations of the Wrecks of HMS Indefatigable and SMS V4

The Opening and Closing Sequences of the Battle of Jutland 1916 Re- examined: archaeological investigations of the wrecks of HMS Indefatigable and SMS V4 Innes McCartney Bournemouth University, Department of Archaeology, Anthropology and Forensic Science, Fern Barrow, Talbot Campus, Poole, Dorset BH12 5BB, UK This paper presents the findings from surveys carried out in 2016 of two wrecks sunk during the Battle of Jutland. The remains of HMS Indefatigable had previously only been partially understood. SMS V4, was found and surveyed for the first time. They represent the first and last ships sunk and allow the timings of the opening and closing of the battle to be established. In the case of HMS Indefatigable, the discovery that the ship broke in two, seemingly unnoticed, substantially revises the narrative of the opening minutes of the battle. Key words: nautical archaeology, battlefield archaeology, conflict archaeology, Battle of Jutland, World War One, Royal Navy. On 31 May 1916, the two most powerful battle-fleets in the world clashed off the coast of Denmark, in what in Britain has become known as the Battle of Jutland. In reality the battle was more of a skirmish from which the German High Seas Fleet, having accidentally run into the British Grand Fleet, was able to extricate itself and escape to base, leaving the British in control of the battlefield. However, in the 16 hours during which this drama played out, 25 ships were sunk, claiming more than 8500 lives. The Grand Fleet suffered 14 of the ships sunk and around 6000 of the lost sailors. More than 5000 of the British dead were lost on five ships that exploded, killing nearly every sailor aboard the ships. -

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic 'Endurance' Expedition

THE IMPERIAL TRANS-ANTARCTIC ‘ENDURANCE’ EXPEDITION LIMITED EDITION PLATINUM PRINTS PHOTOGRAPHS BY FRANK HURLEY Official Expedition Photographer (1) ‘ENDURANCE’ IN FULL SAIL Iconic Print FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (2) ‘ENDURANCE’ CRUSHED BY THE ICE PACKS Iconic Print FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (3) “THE SPECTRE SHIP” Iconic Print FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (4) THE ‘ENDURANCE’ BESET BY PACK ICE FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (5) THE NIGHTWATCHMAN’S STORY FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (6) ENTERING THE POLAR SEA FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (7) FRANK WORSLEY AND LIONEL GREENSTREET LOOKING ACROSS SOUTH GEORGIA HARBOUR FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (8) DAWN AFTER WINTER FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (9) THE OBELISK FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (10) ’ENDURANCE’ FROZEN IN THE ICE FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (11) THE RETURNING SUN FURTHER INFORMATION For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] (12) THE ‘ENDURANCE’ KEELED