AL-FUST at Its Foundation & Early Urban Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meter of Classical Arabic Poetry

Pegs, Cords, and Ghuls: Meter of Classical Arabic Poetry Hazel Scott Haverford College Department of Linguistics, Swarthmore College Fall 2009 There are many reasons to read poetry, filled with heroics and folly, sweeping metaphors and engaging rhymes. It can reveal much about a shared cultural history and the depths of the human soul; for linguists, it also provides insights into the nature of language itself. As a particular subset of a language, poetry is one case study for understanding the use of a language and the underlying rules that govern it. This paper explores the metrical system of classical Arabic poetry and its theoretical representations. The prevailing classification is from the 8th century C.E., based on the work of the scholar al-Khaliil, and I evaluate modern attempts to situate the meters within a more universal theory. I analyze the meter of two early Arabic poems, and observe the descriptive accuracy of al-Khaliil’s system, and then provide an analysis of the major alternative accounts. By incorporating linguistic concepts such as binarity and prosodic constraints, the newer models improve on the general accessibility of their theories with greater explanatory potential. The use of this analysis to identify and account for the four most commonly used meters, for example, highlights the significance of these models over al-Khaliil’s basic enumerations. The study is situated within a discussion of cultural history and the modern application of these meters, and a reflection on the oral nature of these poems. The opportunities created for easier cross-linguistic comparisons are crucial for a broader understanding of poetry, enhanced by Arabic’s complex levels of metrical patterns, and with conclusions that can inform wider linguistic study.* Introduction Classical Arabic poetry is traditionally characterized by its use of one of the sixteen * I would like to thank my advisor, Professor K. -

Saleh Poll Tax December 2011

On the Road to Heaven: Poll tax, Religion, and Human Capital in Medieval and Modern Egypt Mohamed Saleh* University of Southern California (Preliminary and Incomplete: December 1, 2011) Abstract In the Middle East, non-Muslims are, on average, better off than the Muslim majority. I trace the origins of the phenomenon in Egypt to the imposition of the poll tax on non- Muslims upon the Islamic Conquest of the then-Coptic Christian Egypt in 640. The tax, which remained until 1855, led to the conversion of poor Copts to Islam to avoid paying the tax, and to the shrinking of Copts to a better off minority. Using new data sources that I digitized, including the 1848 and 1868 census manuscripts, I provide empirical evidence to support the hypothesis. I find that the spatial variation in poll tax enforcement and tax elasticity of conversion, measured by four historical factors, predicts the variation in the Coptic population share in the 19th century, which is, in turn, inversely related to the magnitude of the Coptic-Muslim gap, as predicted by the hypothesis. The four factors are: (i) the 8th and 9th centuries tax revolts, (ii) the Arab immigration waves to Egypt in the 7th to 9th centuries, (iii) the Coptic churches and monasteries in the 12th and 15th centuries, and (iv) the route of the Holy Family in Egypt. I draw on a wide range of qualitative evidence to support these findings. Keywords: Islamic poll tax; Copts, Islamic Conquest; Conversion; Middle East JEL Classification: N35 * The author is a PhD candidate at the Department of Economics, University of Southern California (E- mail: [email protected]). -

On Body, Soul, and Popular Culture: a Study of the Perception of Plague by Muslim and Coptic Communities in Mamluk Egypt

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences On Body, Soul, and Popular Culture: A Study of the Perception of Plague by Muslim and Coptic Communities in Mamluk Egypt A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts By Mohamed S. Maslouh Under the supervision of Dr. Amina Elbendary September / 2013 The American University in Cairo On Body, Soul, and Popular Culture: A Study of the Perception of Plague by Muslim and Coptic Communities in Mamluk Egypt A Thesis Submitted by Mohamed S. Maslouh To the Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations September /2013 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Master of Arts Has been approved by Dr. Amina Elbendary Thesis Committee Advisor____________________________________________ Assistant Professor, Arab and Islamic Civilizations Department. American University in Cairo. Dr. Nelly Hanna Thesis Committee Reader____________________________________________ Distinguished University Professor, Arab and Islamic Civilizations Department. American University in Cairo. Dr. Adam Talib Thesis Committee Reader____________________________________________ Assistant Professor, Arab and Islamic Civilizations Department. American University in Cairo. _________________ __________ __________________ ____________ Dept. Chair Date Dean of HUSS Date ii Abstract The American University in Cairo On Body, Soul, and Popular Culture: A Study of the Perception of Plague by Muslim and Coptic Communities in Mamluk Egypt By: Mohamed S. Maslouh Supervisor: Dr. Amina Elbendary This thesis studies the Muslim and Coptic medical, theological, and philosophical perceptions of plague in Mamluk Egypt (1250-1517). It also details the responses to mass death caused by plagues in both popular culture and mainstream scholarly works. -

When the Moon Split a Biography of Prophet

When the Moon Split A biography of Prophet Muhammad Compiled by Safiur Rahman Mubarakpuri Edited and Translated by Tabassum Siraj - Michael Richardson Badr Azimabadi 1 2 In the Name of Allah The Most Gracious, the Most Merciful And We have sent you (O’ Muhammad) Not but as a mercy for the ‘Alamin (Mankind, jinn and all that exists). (Surat Al ‘Anbya’ 21: 107) 3 CONTENTS Subject Page Contents 4 From the Author 11 Preface 12 The Prophet Muhammad’s Ancestors 14 The Prophets Tribe 14 Lineage 15 Muhammad is born 18 Foster Brothers 19 In the care of Haleemah Sa’diya 20 Haleemah’s house is unexpectedly blessed 20 Haleemah asks to keep Muhammad longer 21 Muhammad’s chest is opened 21 Muhammad’s time with his mother 21 A grandfather’s affection 22 Under his uncle’s care 22 Bahira’s warning 22 The Battle of Fijar 23 Hilf Al-Fudool 24 Choosing a profession 25 Journey to Syria on business for Khadeejah 25 Marriage to Khadeejah 25 Dispute over the Black Stone 26 Muhammad’s character before Prophethood 28 Portents of Prophethood 29 The First Revelation 29 A hiatus 31 The mission begins 33 The first believers 33 Worship and training of the believers 36 Open propagation of Islam 37 A warning from atop Mount Safa 38 The Quraysh warn pilgrims 41 Various strategies against Islam 42 4 Ridicule, contempt and mockery 43 Diversions 44 Propaganda 44 Argument and quibbling 45 Persecution begins 55 Polytheists avoid openly abusing the Prophet 60 Talks between Abu Talib and the Quraysh 60 The Quraysh challenge Abu Talib 61 The Quraysh make Abu Talib a strange proposal -

The Grain Economy of Mamluk Egypt by Ira M. Lapidus

THE GRAIN ECONOMY OF MAMLUK EGYPT BY IRA M. LAPIDUS (University of California, Berkeley) Scholarly studies of the economy of Egypt in the Middle Ages, from the Fatimid through the Mamluk periods, have stressed two seemingly contradictory themes. On the one hand, the extraordinary involvement of the state in economic affairs is manifest. At different times, and in various ways, the ruling regimes of Egypt monopolized or strictly controlled certain primary or strategic products. Wood and metals, both domestic and imported, were strictly controlled to assure the availability of military supplies. Certain export products like natron were sometimes made state monopolies. So too products of unusual commercial importance were exploited, especially by the Mamluk Sultans, to gain monetary advantages. Sugar production, often in the hands of rulers and oflicials, was also, on occasion, a state monopoly. At another level, the state participated in economic activity it did not monopolize. Either the governing bureaus themselves, or elite members of the regime, were responsible for irrigation and other investments essential to agricultural productivity. In the trading sphere, though state-sponsored trading expeditions are unknown, state support for trade by treaty arrangements, by military and diplomatic protection, and direct participation in the form of investments placed with mer- chants were characteristic activities. How much of the capital of trade was "booty" or political capital we shall never know. In other spheres, state participation gave way to state controls for the purposes of taxation. Regulation of the movements of merchants, or the distribution of goods, facilitated taxation. For religious or moral reasons state controls also extended to the supervision, regulation, or prohibition of certain illicit trades. -

Timeline / 600 to 1700 / EGYPT

Timeline / 600 to 1700 / EGYPT Date Country | Description 619 A.D. Egypt Egypt, Jerusalem and Damascus come under the rule of the Persian Emperor Xerxes II. 627 A.D. Egypt Prophet Muhammad sends a letter to Cyrus, the Byzantine Patriarch of Alexandria and ruler of Egypt, inviting him to accept Islam. Cyrus sends gifts to the Prophet in answer, together with two sisters from Upper Egypt. The Prophet married one of them, called Maria the Copt. She bore him his only son, who died in boyhood. 639 A.D. Egypt The first mosque in Egypt is built in Bilbis, east of the Delta, to honour the martyrs and 120 companions of the Prophet who died in battle there during the Arab invasion of Egypt. It followed the ground plan of the Prophet's mosque in Medina. 641 A.D. Egypt Babylon (the Roman settlement south of present-day Cairo) capitulates to the Muslim armies led by Amr ibn al-'As.The first Islamic capital of Egypt, Fustat, is founded. 655 A.D. Egypt Ali ibn Abi Talib, the Prophet's cousin and companion, isappointed wali (ruler) of Egypt by ‘Uthman ibn ‘Affan, the third Righteous Caliph. 750 A.D. Egypt Egypt comes under the control of the Abbasid Caliphate and al-Askar, the second Islamic capital of Egypt, is founded. Marwan ibn Muhammad, the last Umayyad Caliph in the East, is murdered in Abu Seir, Fayyum, west of the Delta. 764 A.D. Egypt A great famine strikes the country due to the low Nile flood, during the rule of Amir Yazid ibn Hakim al-Mahdi, ruler of the Abbasids. -

Non-Technical Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report

Arab Republic of Egypt Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities European Investment Bank L’Agence Française de Développement (AFD) Construction Authority for Potable Water & Wastewater CAPW Helwan Wastewater Collection & Treatment Project Non-Technical Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report Date of issue: May 2020 Consulting Engineering Office Prof. Dr.Moustafa Ashmawy Helwan Wastewater Collection & Treatment Project NTS ESIA Report Non - Technical Summary 1- Introduction In Egypt, the gap between water and sanitation coverage has grown, with access to drinking water reaching 96.6% based on CENSUS 2006 for Egypt overall (99.5% in Greater Cairo and 92.9% in rural areas) and access to sanitation reaching 50.5% (94.7% in Greater Cairo and 24.3% in rural areas) according to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). The main objective of the Project is to contribute to the improvement of the country's wastewater treatment services in one of the major treatment plants in Cairo that has already exceeded its design capacity and to improve the sanitation service level in South of Cairo at Helwan area. The Project for the ‘Expansion and Upgrade of the Arab Abo Sa’ed (Helwan) Wastewater Treatment Plant’ in South Cairo will be implemented in line with the objective of the Egyptian Government to improve the sanitation conditions of Southern Cairo, de-pollute the Al Saff Irrigation Canal and improve the water quality in the canal to suit the agriculture purposes. This project has been identified as a top priority by the Government of Egypt (GoE). The Project will promote efficient and sustainable wastewater treatment in South Cairo and expand the reclaimed agriculture lands by upgrading Helwan Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) from secondary treatment of 550,000 m3/day to advanced treatment as well as expanding the total capacity of the plant to 800,000 m3/day (additional capacity of 250,000 m3/day). -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced firom the microfilm master. UMT films the text directly fi’om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be fi’om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing fi’om left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Ifowell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF ARABIC RHETORICAL THEORY. 500 C £.-1400 CE. DISSERTATION Presented m Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Khaiid Alhelwah, M.A. -

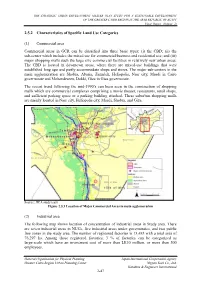

2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) 2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial area Commercial areas in GCR can be classified into three basic types: (i) the CBD; (ii) the sub-center which includes the mixed use for commercial/business and residential use; and (iii) major shopping malls such the large size commercial facilities in relatively new urban areas. The CBD is located in downtown areas, where there are mixed-use buildings that were established long ago and partly accommodate shops and stores. The major sub-centers in the main agglomeration are Shobra, Abasia, Zamalek, Heliopolis, Nasr city, Maadi in Cairo governorate and Mohandeseen, Dokki, Giza in Giza governorate. The recent trend following the mid-1990’s can been seen in the construction of shopping malls which are commercial complexes comprising a movie theater, restaurants, retail shops, and sufficient parking space or a parking building attached. These suburban shopping malls are mainly located in Nasr city, Heliopolis city, Maadi, Shobra, and Giza. Source: JICA study team Figure 2.5.3 Location of Major Commercial Areas in main agglomeration (2) Industrial area The following map shows location of concentration of industrial areas in Study area. There are seven industrial areas in NUCs, five industrial areas under governorates, and two public free zones in the study area. The number of registered factories is 13,483 with a total area of 76,297 ha. Among those registered factories, 3 % of factories can be categorized as large-scale which have an investment cost of more than LE10 million, or more than 500 employees. -

The Archaeology and Heritage of the Sudanese Red Sea Region: Importance, Findings, and Challenges

The Archaeology and Heritage of the Sudanese Red Sea Region: Importance, Findings, and Challenges AHMED ADAM Head Department of Archaeology - University of Khartoum Director of the Red Sea Project for Archaeological Research Abstract This paper seeks to shed a high light on the archaeological sites discovered in the area of Suakin, Arkaweet, and Sinkat as a part of the project of the department of Archaeology ß university of Khartoum, so, the archaeological sites discovered in this region belong to different periods such as Pre-Historic, Medieval, Islamic, and others are unknown, which means that the region used to link the Red Sea Cultures with those on the central Sudan and Egypt far north and Eretria in the east. Through this study I am also seeking to evaluate the field work (Archaeological and Ethnographic) conducted in the area of Arkaweet and Sinkat town, and Suakin port, then to put a plan for the managing and protecting the archaeologi- cal sites and ethnographic materials. Therefore I will follow or apply a number of approaches in this study such as description, survey analysis of the sites and its contents as well a comparison will be made between the results of the present study with the results of the previous studies in the field of archeology and ethnography conducted on other sites in the Sudanese Red Sea Region. The historical sources will also be compared with the study findings. Keywords Red Sea, Archaeology, Heritage, Sudan, Survey, Suakin 188 1. INTRODUCTION The Red Sea lies in an ideal geographical location between eastern and west- ern seas in general, and between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean in particular. -

Indian Trade Cloth in Egypt: the Newberry Collection

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1990 Indian Trade Cloth in Egypt: The Newberry Collection Ruth Barnes Ashmolean Museum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Barnes, Ruth, "Indian Trade Cloth in Egypt: The Newberry Collection" (1990). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 594. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/594 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -179- Indian Trade Cloth in Egypt: holdings are vast by comparison: there is a total of 1225 The Newberry Collection block-printed fragments. The size is matched by quality and variation of design; virtually any pattern known in this kind RUTH BARNES of textile is well represented, and there are pieces which are Ashiaolean Museum probably unique.3 However, the collection is not widely known, Oxford and until very recently (May 1990) it could not be used as research material, as the fragments had not been properly The Department of Eastern Art in the Ashmolean Museum, accessioned into the Department's holdings, hence had no Oxford, holds what is undoubtably one of the largest single number or" other means -of identification which made them collections of block-printed textiles produced in India, but available as a reference. -

All Rights Reserved

ProQuest Number: 10731409 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731409 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES (University of London) MALET STREET, LONDON, WC1 E 7HP DEPARTMENT OF THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Telegrams: SOASUL. LONDON W.C.I Telephone: 01-637 2388 19 March 1985 To whom it may concern Miss Salah's thesis, "A critical edition of al-Muthul 1ala Kitab al-Muqarrab fi al-Nahw by Ibn 'Usfur al-Ishbil-i" , has this month been examined and accepted by the University of London for the degree of Ph.D. It is a well executed piece of text editing, and I consider it worthy of publication. H .T. - Norris Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies in the University of London A CRITICAL EDITION of AL-MUTHUL CALA KITAB AL-MUQARRAB FI AL-NAHW by IBN CUSFUR AL-ISHBILI ^VOIJJMEKT ~ ' 1 v o l C/nUj rcccwed //; /.A /• *.' e^ f EDITED by FATHIEH TAWFIQ SALAH Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1985 DEDICATION to My late father Who, since my childhood, used to encourage me in my studies and who always used to support me by giving me a feeling of trust, confidence and strong hope of success.