The Criminologist Within by Patrick Gerkin1 Grand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alshire Records Discography

Alshire Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Alshire International Records Discography Alshire was located at P.O. Box 7107, Burbank, CA 91505 (Street address: 2818 West Pico Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90006). Founded by Al Sherman in 1964, who bought the Somerset catalog from Dick L. Miller. Arlen, Grit and Oscar were subsidiaries. Alshire was a grocery store rack budget label whose main staple was the “101 Strings Orchestra,” which was several different orchestras over the years, more of a franchise than a single organization. Alshire M/S 3000 Series: M/S 3001 –“Oh Yeah!” A Polka Party – Coal Diggers with Happy Tony [1967] Reissue of Somerset SF 30100. Oh Yeah!/Don't Throw Beer Bottles At The Band/Yak To Na Wojence (Fortunes Of War)/Piwo Polka (Beer Polka)/Wanda And Stash/Moja Marish (My Mary)/Zosia (Sophie)/Ragman Polka/From Ungvara/Disc Jocky Polka/Nie Puki Jashiu (Don't Knock Johnny) Alshire M/ST 5000 Series M/ST 5000 - Stephen Foster - 101 Strings [1964] Beautiful Dreamer/Camptown Races/Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair/Oh Susanna/Old Folks At Home/Steamboat 'Round The Bend/My Old Kentucky Home/Ring Ring De Bango/Come, Where My Love Lies Dreaming/Tribute To Foster Medley/Old Black Joe M/ST 5001 - Victor Herbert - 101 Strings [1964] Ah! Sweet Mystery Of Life/Kiss Me Again/March Of The Toys, Toyland/Indian Summer/Gypsy Love Song/Red Mill Overture/Because You're You/Moonbeams/Every Day Is Ladies' Day To Me/In Old New York/Isle Of Our Dreams M/S 5002 - John Philip Sousa, George M. -

September 15, 1971 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD -HOUSE 31985 "'EFECTUPON OTHER LAW Traveler and the Vacation Traveler, the Forward

September 15, 1971 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD -HOUSE 31985 "'EFECTUPON OTHER LAW traveler and the vacation traveler, the forward. About 700 Negro students will be "SEC. 718. Nothing contained in this Act person who wants the convenience and distributed in other County primary schools shall relieve any Government agency or offi- flexibility of individual, as well as the by busing. This plan is opposed by some cial of its or his primary responsibility to black parents on the grounds that only Negro assure nondiscrimination in employment as person who wants the economic advan- students will be bused. They have proposed required by the Constitution, statutes, and tages of group travel. a plan whereby about 80 percent of the black Executive orders." A balanced air transportation system students are bused out of the Drew area, and SEC. 12. New section 717, added by section is vitally necessary to insure the survival over 1,000 white students from other schools 11 of this Act, shall become effective six of the scheduled carriers who, despite the are bused, many into the Drew area. months after the date of enactment of this increase in air travel, cannot make a It is understandable that the black par- Act. reasonable profit due to the archaic ents of Drew School would resent the fact that the only neighborhood school disrupted Mr. DENT. Mr. Chairman, move that regulations which now prevail. by desegregation is theirs. However, there is the committee do now rise. Basic to the establishment of such a no way to avoid disruption of Drew as a The motion was agreed to. -

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

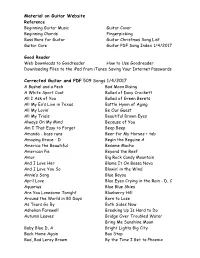

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Memphis Jug Baimi

94, Puller Road, B L U E S Barnet, Herts., EN5 4HD, ~ L I N K U.K. Subscriptions £1.50 for six ( 54 sea mail, 58 air mail). Overseas International Money Orders only please or if by personal cheque please add an extra 50p to cover bank clearance charges. Editorial staff: Mike Black, John Stiff. Frank Sidebottom and Alan Balfour. Issue 2 — October/November 1973. Particular thanks to Valerie Wilmer (photos) and Dave Godby (special artwork). National Giro— 32 733 4002 Cover Photo> Memphis Minnie ( ^ ) Blues-Link 1973 editorial In this short editorial all I have space to mention is that we now have a Giro account and overseas readers may find it easier and cheaper to subscribe this way. Apologies to Kees van Wijngaarden whose name we left off “ The Dutch Blues Scene” in No. 1—red faces all round! Those of you who are still waiting for replies to letters — bear with us as yours truly (Mike) has had a spell in hospital and it’s taking time to get the backlog down. Next issue will be a bumper one for Christmas. CONTENTS PAGE Memphis Shakedown — Chris Smith 4 Leicester Blues Em pire — John Stretton & Bob Fisher 20 Obscure LP’ s— Frank Sidebottom 41 Kokomo Arnold — Leon Terjanian 27 Ragtime In The British Museum — Roger Millington 33 Memphis Minnie Dies in Memphis — Steve LaVere 31 Talkabout — Bob Groom 19 Sidetrackin’ — Frank Sidebottom 26 Book Review 40 Record Reviews 39 Contact Ads 42 £ Memphis Shakedown- The Memphis Jug Band On Record by Chris Smith Much has been written about the members of the Memphis Jug Band, notably by Bengt Olsson in Memphis Blues (Studio Vista 1970); surprisingly little, however has got into print about the music that the band played, beyond general outline. -

Views and Opinions Expressed in This Document Are Those of the Author and Do Not Necessarily

Department of Environmental Studies DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PAGE The undersigned have examined the dissertation entitled: Ramapough/Ford: The Impact and Survival of an Indigenous Community in the Shadow of Ford Motor Company’s Toxic Legacy presented by Chuck Stead candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that it is accepted. Committee Chair Name: Alesia Maltz Title/Affiliation: Antioch University Committee Member Name: Charlene DeFreese Title/Affiliation: Ramapough Lenape Nation Committee Member Name: Michael Edelstein Title/Affiliation: Ramapo College of New Jersey Committee Member Name: Tania Schusler Title/Affiliation: Antioch University Defense Date: August 22, 2014 Ramapough/Ford: The Impact and Survival of an Indigenous Community in the Shadow of Ford Motor Company’s Toxic Legacy By: Chuck Stead A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Environmental Studies at Antioch University New England Committee: Alesia Maltz, Ph.D. (Chair) Tania Schusler, Ph.D. Michael Edelstein, Ph.D. Sub-Chief Charlene DeFreese 2015 The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the reviewers or Antioch University. i This is dedicated to the elders. ii Acknowledgments The author would like to thank Antioch School of Environmental Studies, and the Doctorial Committee, Dr. Michael Edelstein, Dr. Tania Shuster, Charlene Defreese and Dr. Alesia Maltz for their guidance, as well as my cohort colleague Claudia Ford. I would also like to thank the members of the Ramapo Lenape Nation especially Chief Perry, Chief Mann, and Vivian Milligan for their support and guidance. -

Titelname Im Stil Von Künstler

Titelname Im Stil von Künstler Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Back in the night Dr. Feelgood Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Revival Big River Johnny Cash Big Wheel's Roling Merle Haggard Buicks To The Moon Alan Jackson Bye Bye Love - Everly Brothers Everly Brothers Chattahoochee Alan Jackson Cotton Field - P.G.Rider P.G.Ride Country Boy Alan Jackson Cry, Cry, Cry Johnny Cash Daddy Sang Bass Johnny Cash Dail In Country-E-Dur Michael Ballew Dark Haired Boy Roseanne Cash Der Wilde, Wilde Westen Truck Stop Designated Drinker Alan Jackson DixielandDelight-CRAlabama Alabama Doggone Lonesome Johnny Cash Doing My Time Roy & The Rebels Don't Rock The Jukebox Alan Jackson Don't You Wish It Was True - CDur John Fogerty Drivin' My Life Away Eddie Rabbit Folsom Prison Blues Johnny Cash Forever And Ever - P.G.Rider P.G.Rider Freight Train Alan Jackson Seite 1 von 3 Titelname Im Stil von Künstler Give My Love To Rose Johnny Cash Gonna Come Back As A Country Song Alan Jackson Good Hearded Woman Country Rebels Good Time Alan Jackson Green Back Dollar Country Rebels Happy Birthday Country Rebels Have You Ever Seen the Rain (with Alan Jackson) John Fogerty Heading West - P.G.Rider P.G.Rider I Walk The Line Johnny Cash It Must Be Love Alan Jackson It's Alright To Be A Redneck Alan Jackson Jetplane John Denver Johnny B Good-ADur Chuck Berry Kiss An Angel Good Mornin' Jackson, Alan Livin' On Love Alan Jackson Lonesome Me Johnny Cash Mary Lou Ricky Nelson MephisTennessee Johnny Rivers Mercury Blues Alan Jackson MountainMusic-CRVersion Alabama Nineteen -

Unauthorized Use of Popular Music in Presidential Campaigns

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 14 Number 1 Article 5 9-1-1993 Every Little Thing I Do (Incurs Legal Liability): Unauthorized use of Popular Music in Presidential Campaigns Erik Gunderson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Erik Gunderson, Every Little Thing I Do (Incurs Legal Liability): Unauthorized use of Popular Music in Presidential Campaigns, 14 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 137 (1993). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol14/iss1/5 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVERY LITTLE THING I DO (INCURS LEGAL LIABILITY): UNAUTHORIZED USE OF POPULAR MUSIC IN PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGNS I. INTRODUCTION: A COMMON, IF ILLEGAL, PRACTICE In 1984, Ronald Reagan's re-election campaign used the Bruce Springsteen song, "Born in the U.S.A.,"' to convey energy and patriotism to the crowds of Reagan supporters and the ever vigilant media.2 Bruce Springsteen himself did not approve of or authorize the use of the song.3 Following the Reagan campaign's example, the practice of a political cam- has become a feature taken paign using popular music without authorization 4 almost for granted in the contemporary political landscape. This Comment will argue that the common practice of using popular songs without permission in presidential campaigns is illegal. -

Course Description, Class Outline and Syllabus Instructor: Peter Elman

Course description, class outline and syllabus Instructor: Peter Elman Title: “A Round-Trip Road Trip of Country Music, 1950-present: From Nashville to California to Texas--and back.” Course Description: An up close and personal look at the golden era of American country music, this class will explore key movements that contributed to the explosive growth of country music as an industry, art form and subculture. The first half of this course will focus on three major regions: Nashville, California and Texas, and concentrate on the period 1950-1975. The second half will look at the women of country, discuss the making of a country song and record, look at the work of five great songsmiths, visit the country music of the 1980’s, and end with an examination of Americana music. The course will do this through lectures, photographs, recorded music, film clips, question and answer sessions, and the use of live music. The instructor will play piano, guitar and sing, and will choose appropriate examples from each region, period and style. - - - - - - - - - - - Course outline by week, with syllabus; suggested reading, listening and viewing Week one: The rise of “honky-tonk” music, 1940-60: Up from bluegrass—the roots of country music. Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams, Kitty Wells, Lefty Frizzell, Porter Wagoner, Jim Reeves, Webb Pierce, Ray Price, Hank Lochlin, Hank Snow, and the Grand Old Opry. Reading: The Nashville sound: bright lights and country music Paul Hemphill, 1970-- the definitive portrait of the roots of country music. Listening: 20 of Hank Williams Greatest Hits, Mercury, 1997 30 #1 Country Hits of the 1950s, 3-disc set, Direct Source, 1997 Viewing: O Brother Where Art Thou, 2000, by the Coen brothers America's Music: The Roots of Country 1996, three-part, six episode documentary. -

Willie Nelson

LESSON GUIDE • GRADES 3-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Introduction 4 About the Guide 5 Pre and Post-Lesson: Anticipation Guide 6 Lesson 1: Introduction to Outlaws 7 Lesson 1: Worksheet 8 Lyric Sheet: Me and Paul 9 Lesson 2: Who Were The Outlaws? 10 Lesson 3: Worksheet 12 Activities: Jigsaw Texts 14 Lyric Sheet: Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way 15 Lesson 4: T for Texas, T for Tennessee 16 Lesson 5: Literary Lyrics 17 Lyric Sheet: Daddy What If? 18 Lyric Sheet: Act Naturally 19 Complete Tennessee Standards 21 Complete Texas Standards 23 Biographies 3-6 Table of Contents 2 Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s examines how the Outlaw movement greatly enlarged country music’s audience during the 1970s. Led by pacesetters such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Bobby Bare, artists in Nashville and Austin demanded the creative freedom to make their own country music, different from the pop-oriented sound that prevailed at the time. This exhibition also examines the cultures of Nashville and fiercely independent Austin, and the complicated, surprising relationships between the two. Artwork by Sam Yeates, Rising from the Ashes, Willie Takes Flight for Austin (2017) 3-6 Introduction 3 This interdisciplinary lesson guide allows classrooms to explore the exhibition Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s on view at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum® from May 25, 2018 – February 14, 2021. Students will examine the causes and effects of the Outlaw movement through analysis of art, music, video, and nonfiction texts. In doing so, students will gain an understanding of the culture of this movement; who and what influenced it; and how these changes diversified country music’s audience during this time. -

Sweet & Lowdown Repertoire

SWEET & LOWDOWN REPERTOIRE COUNTRY 87 Southbound – Wayne Hancock Johnny Yuma – Johnny Cash Always Late with Your Kisses – Lefty Jolene – Dolly Parton Frizzell Keep on Truckin’ Big River – Johnny Cash Lonesome Town – Ricky Nelson Blistered – Johnny Cash Long Black Veil Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain – E Willie Lost Highway – Hank Williams Nelson Lover's Rock – Johnny Horton Bright Lights and Blonde... – Ray Price Lovesick Blues – Hank Williams Bring It on Down – Bob Wills Mama Tried – Merle Haggard Cannonball Blues – Carter Family Memphis Yodel – Jimmy Rodgers Cannonball Rag – Muleskinner Blues – Jimmie Rodgers Cocaine Blues – Johnny Cash My Bucket's Got a Hole in It – Hank Cowboys Sweetheart – Patsy Montana Williams Crazy – Patsy Cline Nine Pound Hammer – Merle Travis Dark as a Dungeon – Merle Travis One Woman Man – Johnny Horton Delhia – Johnny Cash Orange Blossom Special – Johnny Cash Doin’ My Time – Flatt And Scruggs Pistol Packin Mama – Al Dexter Don't Ever Leave Me Again – Patsy Cline Please Don't Leave Me Again – Patsy Cline Don't Take Your Guns to Town – Johnny Poncho Pony – Patsy Montana Cash Ramblin' Man – Hank Williams Folsom Prison Blues – Johnny Cash Ring of Fire – Johnny Cash Ghost Riders in the Sky – Johnny Cash Sadie Brown – Jimmie Rodgers Hello Darlin – Conway Twitty Setting the Woods on Fire – Hank Williams Hey Good Lookin’ – Hank Williams Sitting on Top of the World Home of the Blues – Johnny Cash Sixteen Tons – Merle Travis Honky Tonk Man – Johnny Horton Steel Guitar Rag Honky Tonkin' – Hank Williams Sunday Morning Coming -

How to Write a "Catchy" Song Title by Vince Corozine (ASCAP)

How To Write a "Catchy" Song Title by Vince Corozine (ASCAP) The song title, "You Can't Take That Away From Me" immediately raises the question, "What can't you take away from me?" It drives the reader to want to investigate further and find out what the lyric says. It peaks our interest and arouses one's curiosity. A "catchy" song title will perk the interest of the listener and lead them to want to pursue more information about what the song is about. When selecting a song title one must ask, "What is the song about?" Is it about winning love, losing love, rival love, unrequited love? The topic of the song must be crystal clear in the mind of the songwriter and this central idea must be conveyed to the listener 1. What makes a good title? The title of a song should summarize the essence of the song and should be used in a prominent place in the song, like the first line of "Night and Day," or at the end of each verse as in "New York State of Mind," or at the very end of the song as in "You'll Never Walk Alone." Some of the strongest and best titles contain language that paints a verbal picture or suggests an image in the mind of the listener "A Boy Named Sue," or one that pertains to a color "Blue Suede Shoes." or one that mentions a place "Chicago," or represents a name "Michelle," or suggests a date "April Showers." 2. Can I use a title that already exists? It is fascinating to know that song titles, book titles, movie titles and so on are not copyrightable and therefore can be used freely by anybody without cost or paying royalties. -

The Big List (My Friends Are Gonna Be) Strangers Merle Haggard 1948 Barry P

THE BIG LIST (MY FRIENDS ARE GONNA BE) STRANGERS MERLE HAGGARD 1948 BARRY P. FOLEY A LIFE THAT'S GOOD LENNIE & MAGGIE A PLACE TO FALL APART MERLE HAGGARD ABILENE GEORGE HAMILITON IV ABOVE AND BEYOND WYNN STEWART-RODNEY CROWELL ACT NATURALLY BUCK OWENS-THE BEATLES ADALIDA GEORGE STRAIT AGAINST THE WIND BOB SEGER-HIGHWAYMAN AIN’T NO GOD IN MEXICO WAYLON JENNINGS AIN'T LIVING LONG LIKE THIS WAYLON JENNINGS AIN'T NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERS AIRPORT LOVE STORY BARRY P. FOLEY ALL ALONG THE WATCHTOWER BOB DYLAN-JIMI HENDRIX ALL I HAVE TO DO IS DREAM EVERLY BROTHERS ALL I HAVE TO OFFER IS ME CHARLIE PRIDE ALL MY EX'S LIVE IN TEXAS GEORGE STRAIT ALL MY LOVING THE BEATLES ALL OF ME WILLIE NELSON ALL SHOOK UP ELVIS PRESLEY ALL THE GOLD IN CALIFORNIA GATLIN BROTHERS ALL YOU DO IS BRING ME DOWN THE MAVERICKS ALMOST PERSUADED DAVID HOUSTON ALWAYS LATE LEFTY FRIZZELL-DWIGHT YOAKAM ALWAYS ON MY MIND ELVIS PRESLEY-WILLIE NELSON ALWAYS WANTING YOU MERLE HAGGARD AMANDA DON WILLIAMS-WAYLON JENNINGS AMARILLO BY MORNING TERRY STAFFORD-GEORGE STRAIT AMAZING GRACE TRADITIONAL AMERICAN PIE DON McLEAN AMERICAN TRILOGY MICKEY NEWBERRY-ELVIS PRESLEY AMIE PURE PRAIRIE LEAGUE ANGEL FLYING TOO CLOSE WILLIE NELSON ANGEL OF LYON TOM RUSSELL-STEVE YOUNG ANGEL OF MONTGOMERY JOHN PRINE-BONNIE RAITT-DAVE MATTHEWS ANGELS LIKE YOU DAN MCCOY ANNIE'S SONG JOHN DENVER ANOTHER SATURDAY NIGHT SAM COOKE-JIMMY BUFFET-CAT STEVENS ARE GOOD TIMES REALLY OVER MERLE HAGGARD ARE YOU SURE HANK DONE IT WAYLON JENNINGS AUSTIN BLAKE SHELTON BABY PLEASE DON'T GO MUDDY WATERS-BIG JOE WILLIAMS BABY PUT ME ON THE WAGON BARRY P.