H.E.L.P : a Creative Exercise in Feminism and the Buddy Comedy. Bayne M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design Guidelines Manufacturer Guidelines

Congratulations on your participation in the tenth annual Prêt-A-Porter fashion event! Friday May 12th, 7:00 PM EXDO 1399 35th Street Denver, CO 80205 _________________________________________________________________________________________ This document should answer most of your questions about design, materials, and event logistics including: 1. Design Teams 6. Critical Dates 2. Manufacturer Guidelines 7. Model Information 3. Judging Criteria 8. Run-through of the event 4. Prizes 9. Frequently Asked Questions 5. Tickets __________________________________________________________________________________________ ► Design Guidelines Each Design Team will be comprised of up to five members plus a model. We encourage the model to be an integral part of the team and someone with your firm or manufacturer. No hired professional models. The intent of the event is to showcase your manufacturer’s product by using it in a unique and creative way. Look to media coverage of the couture and ready-to-wear fashion shows in New York, Paris, London and Milan for inspiration. Fabrication of the materials into a garment is the responsibility of the design team. We encourage your team to sew and assemble your creation using your own methods. With that said, however, you are allowed to have a seamstress outside of your team help you assemble your garment. This cost would be the responsibility of the design team. However only 10% of the entire garment can be sewn or fabricated by someone outside of your team. ► Manufacturer Guidelines The manufacturer’s only responsibility to the team is to supply the materials for the construction of the garment. The manufacturer is not required to help fabricate the garment; however, with past events, the most successful entries have featured collective collaboration between the design team and the manufacturer and pushed materials to perform in new ways. -

IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Cineteca Del Comune Di Bologna

XXXVII Mostra Internazionale del Cinema Libero IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Cineteca del Comune di Bologna XXII edizione / 22nd Edition Sabato 28 giugno - Sabato 5 luglio / Saturday 28 June - Saturday 5 July Questa edizione del festival è dedicata a Vittorio Martinelli This festival’s edition is dedicated to Vittorio Martinelli IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Via Azzo Gardino, 65 - tel. 051 219 48 14 - fax 051 219 48 21 - cine- XXII edizione [email protected] Segreteria aperta dalle 9 alle 18 dal 28 giugno al 5 luglio / Secretariat Con il contributo di / With the financial support of: open June 28th - July 5th -from 9 am to 6 pm Comune di Bologna - Settore Cultura e Rapporti con l'Università •Cinema Lumière - Via Azzo Gardino, 65 - tel. 051 219 53 11 Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio in Bologna •Cinema Arlecchino - Via Lame, 57 - tel. 051 52 21 75 Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali - Direzione Generale per il Cinema Modalità di traduzione / Translation services: Regione Emilia-Romagna - Assessorato alla Cultura Tutti i film delle serate in Piazza Maggiore e le proiezioni presso il Programma MEDIA+ dell’Unione Europea Cinema Arlecchino hanno sottotitoli elettronici in italiano e inglese Tutte le proiezioni e gli incontri presso il Cinema Lumière sono tradot- Con la collaborazione di / In association with: ti in simultanea in italiano e inglese Fondazione Teatro Comunale di Bologna All evening screenings in Piazza Maggiore, as well as screenings at the L’Immagine Ritrovata Cinema Arlecchino, will be translated into Italian -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000 -

PDF Download Millinery Ebook Free Download

MILLINERY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Estelle Ramousse,Fabienne Gambrelle | 120 pages | 09 Jul 2010 | Search Press Ltd | 9781844485055 | English | Tunbridge Wells, United Kingdom Millinery PDF Book Cart 0. Retrieved 8 November Buckram Crowns The traditional methods of blocking with buckram are detailed in this lesson. This is a partial list of people who have had a significant influence on hat-making and millinery. You will just need access to a computer or mobile device and an internet connection. A provided index helps direct you to resources available in multiple countries to cover the steps you need to take to set up your business. Lace Millinery Deluxe Course. Couture Parisisal Deluxe Course. Signature Feather Flowers Deluxe Course. Manufacture and design of hats and headwear. Love words? Words nearby millinery millimetre , millimicron , millimole , milline , milliner , millinery , milling , milling machine , Millington , million , millionaire. Customers will love this simple couture touch your new linings will add. Namespaces Article Talk. Black Then. Christie Murray is a Milliner based in Australia and has a background in fashion business and education. It is broken in to easy to follow steps and straightforward worksheets that Christie guides you through. A Rendezvous With Hats Course. Search courses. Bridal Headwear Deluxe Course. Make a sturdy base and learn how to keep fabric stable on this foundation. Felt Hats Basics Learn how to shape fabulous felt. I have limited business experience, will this course be too difficult? Millinery is sold to women, men and children, though some definitions limit the term to women's hats. Customise Basic Blocks In this lesson you will learn to maximise the use of your first blocks to create different styles including double blocking methods. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

A Field Guide Not to the Join NWTA Us?

Why A Field Guide not to the join NWTA us? Revolutionary War reenacting is a fun, exciting and educational hobby in which the entire family may participate. If you and your family are interested in joining an NWTA unit, talk to some people around camp, they will be more than happy to answer questions. Check out our website, www.nwta.com for more information about our organization, our units and our event schedule and locations. Or contact the Loyal Irish Volunteer Recruit- ing Coordinator or the Adjutant to find out more about joining our organization. Recruiting: [email protected] Membership: [email protected] A Field Guide to The NWTA © 2014 North West Territory Alliance The North West Territory Alliance No reproduction without prior written permission Contact the Adjutant Recreating the American Revolution [email protected] www.nwta.com 1775-1783 28 18th century warfare is thought by many to be a sluggish, slow-moving affair Welcome to The NWTA where armies moved in great masses and prevailed over each other with enor- mous casualties. In fact, the maneuvers and drills used by 18th century armies The North West Territory Alliance is a non-profit educational organization that were designed to operate at maximum speed of horses and men on the battlefield. studies and recreates the culture and arts of the time of the American Revolution, Maintaining orderly formations was important to allow the most effective use of 1775-1783. We strive to duplicate the uniforms, weapons, battlefield tactics, the main infantry weapons — the musket, bayonet and cannon — for maximum camp life and civilian life of the time as accurately as possible. -

Nømädnêss: the Gospel According to Wanda B

Nømädnêss: The Gospel According to Wanda B. Lazarus A novel by Lynn M. Joffe As part of the requirement for a dissertation for the degree of Master of Arts by Research (Creative Writing) submitted to the Faculty of Arts, School of Literature, Language and Media, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. © Lynn M. Joffe. Johannesburg, 2017. Student # 1305057 - 1 - Contents Book Header Page I ‘Tummel in the Temple’ Jerusalem 33 CE 3 II ‘Zenobia in Chains’ Palmyra 272 CE 38 III ‘The Gopi Bat Mitzvah’ Cochin 666 CE 65 IV ‘To Live or Die in Magao’ Dunguang Caves 1054 CE 84 V ‘Ballad of the Occitan’ Albi 1229 CE 104 VI ‘The Wandering Years’ Europe 1229-1234 CE 121 VII ‘The Odalisque of Swing’ Istanbul 1558 CE 134 VIII ‘Commedia in Cremona’ Italy 1689 CE 152 IX ‘Terpsichore’s Plectrum’ London 1842 CE 177 X ‘Razzie and the Romany Creams’ St. Petersburg 1916 204 XI ‘Made in Manhattan’ New Canaan 1942 226 XII ‘The Land of the Lemba’ Johannesburg 1999 254 XIII ‘Aurora Nights’ Geilo 2016 CE 278 - 2 - Book I: ‘Tummel in the Temple’ Jerusalem 33 CE i If we hadn’t been following Hadassah’s pomegranate all over the known world, we’d never have wound up in Bethany. Carta would still be alive. And I’d be mortal. But that’s not how things panned out. A Painted Lady flaps her wings and all that jazz. The Lembas remember it differently, but they were always going to write their own version anyway. I was there. I saw it all. -

International Airport Codes

Airport Code Airport Name City Code City Name Country Code Country Name AAA Anaa AAA Anaa PF French Polynesia AAB Arrabury QL AAB Arrabury QL AU Australia AAC El Arish AAC El Arish EG Egypt AAE Rabah Bitat AAE Annaba DZ Algeria AAG Arapoti PR AAG Arapoti PR BR Brazil AAH Merzbrueck AAH Aachen DE Germany AAI Arraias TO AAI Arraias TO BR Brazil AAJ Cayana Airstrip AAJ Awaradam SR Suriname AAK Aranuka AAK Aranuka KI Kiribati AAL Aalborg AAL Aalborg DK Denmark AAM Mala Mala AAM Mala Mala ZA South Africa AAN Al Ain AAN Al Ain AE United Arab Emirates AAO Anaco AAO Anaco VE Venezuela AAQ Vityazevo AAQ Anapa RU Russia AAR Aarhus AAR Aarhus DK Denmark AAS Apalapsili AAS Apalapsili ID Indonesia AAT Altay AAT Altay CN China AAU Asau AAU Asau WS Samoa AAV Allah Valley AAV Surallah PH Philippines AAX Araxa MG AAX Araxa MG BR Brazil AAY Al Ghaydah AAY Al Ghaydah YE Yemen AAZ Quetzaltenango AAZ Quetzaltenango GT Guatemala ABA Abakan ABA Abakan RU Russia ABB Asaba ABB Asaba NG Nigeria ABC Albacete ABC Albacete ES Spain ABD Abadan ABD Abadan IR Iran ABF Abaiang ABF Abaiang KI Kiribati ABG Abingdon Downs QL ABG Abingdon Downs QL AU Australia ABH Alpha QL ABH Alpha QL AU Australia ABJ Felix Houphouet-Boigny ABJ Abidjan CI Ivory Coast ABK Kebri Dehar ABK Kebri Dehar ET Ethiopia ABM Northern Peninsula ABM Bamaga QL AU Australia ABN Albina ABN Albina SR Suriname ABO Aboisso ABO Aboisso CI Ivory Coast ABP Atkamba ABP Atkamba PG Papua New Guinea ABS Abu Simbel ABS Abu Simbel EG Egypt ABT Al-Aqiq ABT Al Baha SA Saudi Arabia ABU Haliwen ABU Atambua ID Indonesia ABV Nnamdi Azikiwe Intl ABV Abuja NG Nigeria ABW Abau ABW Abau PG Papua New Guinea ABX Albury NS ABX Albury NS AU Australia ABZ Dyce ABZ Aberdeen GB United Kingdom ACA Juan N. -

The Pipes and Drums of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards (Carabiniers and Greys)

The Pipes and Drums of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards (Carabiniers and Greys) The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards are Scotland`s senior regiment and only regular cavalry regiment. The Regiment was formed in 1971 from the amalgamation of the 3rd Carabiniers (whom were themselves the result of the amalgamation of the 6th Dragoon Guards the Carabiniers and the 3rd the Prince of Wales Dragoon Guards in 1922) and The Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons). The history of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards is therefore the record of three ancient regiments. Through The Royal Scots Greys, whose predecessors were raised by King Charles II in 1678 the Regiment can claim to be the oldest surviving Cavalry of the Line in The British Army. Displayed on the Regimental Standard are just fifty of the numerous battle honours won in wars and campaigns spanning three centuries. The most celebrated of these are Waterloo, Balaklava and Nunshigum. At the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 the Scots Greys took part in the famous Charge of the Union Brigade. It was here that Sergeant Ewart captured the Imperial Eagle, the Standard of Napoleon`s 45th Regiment. This standard is now displayed in the Home Headquarters of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards at Edinburgh Castle and in commemoration the Eagle forms part of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards cap badge. During the Crimean War in 1854 two Victoria Crosses were awarded at the Battle of Balaklava against the Russians in the famous Charge of the Heavy Brigade. In World War II the battle honour Nunshigum was won by B Squadron of the 3rd Carabiniers against the Japanese in Burma. -

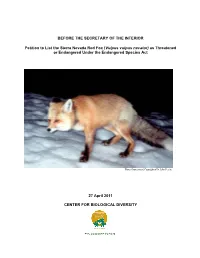

Sierra Nevada Red Fox (Vulpus Vulpus Necator) As Threatened Or Endangered Under the Endangered Species Act

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR Petition to List the Sierra Nevada Red Fox (Vulpus vulpus necator) as Threatened or Endangered Under the Endangered Species Act Photo Courtesy and Copyright of Dr. John Perrine 27 April 2011 CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY - 1 - 27 April 2011 Mr. Ken Salazar Mr. Ren Lohoefener Secretary of the Interior Pacific Southwest Regional Director Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 18th and "C" Street, N.W. 2800 Cottage Way, Room W-2605 Washington, D.C. 20240 Sacramento, CA 95825 RE: PETITION TO LIST SIERRA NEVADA RED FOX (Vulpus vulpus necator) AS A THREATENED OR ENDANGERED SPECIES AND TO DESIGNATE CRITICAL HABITAT CONCURRENT WITH LISTING. Dear Mr. Salazar and Mr. Lohoefener: The Sierra Nevada red fox (Vulpus vulpus necator) is subspecies of red fox that historically ranged from the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains northward through the southern Cascade Mountains of California and Oregon. Despite 31 years of protection as a threatened species under the California Endangered Species Act, Sierra Nevada red fox remains critically endangered and in imminent danger of extinction: it is today restricted to two small California populations; one near Lassen Peak with fewer than 20 known foxes and a second near Sonora Pass with only three known foxes. The total number of remaining foxes is likely less than 50; it could be less than 20. Its perilously small population size makes it inherently vulnerable to extinction, and sharply magnifies the extinction potential of several threats. None of those threats are abated by existing regulatory mechanisms. Therefore, pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. -

Read Book Hats Ebook

HATS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gmc Editors,GMC,Guild of Master Craftsman | 156 pages | 03 Apr 2012 | Guild of Master Craftsman Publications Ltd | 9781861088666 | English | East Sussex, United Kingdom Hats PDF Book However, some dictionaries indicate that the word may be considered offensive in all contexts today. Worn by — and so closely associated with — the character Sherlock Holmes. The quality of these promotions will reflect the quality of your brand! Conical Asian hat. If you find an advertised price lower than ours from a legitimate Internet dealer and meet the eligibility requirements, we will match that price. CST or the next business day 3. Shaped head covering, having a brim and a crown, or one of these. For other uses, see Hat disambiguation and Hats disambiguation. We apologize for any inconvenience. Clear Filters. Archived from the original on January 30, View All Filters by exiting Colors filter. Some exclusions apply, bikes with assembly are not available for curbside pickup Limited Covid Shipping Restrictions Due to Covid many shipping carriers are experiencing delays in specific regions of the country. Find Your Hat Size. Oversized Items A number of items require special shipping and handling due to their larger size. If you need any help exploring our collections or finding the perfect fit, check out our hat guides or reach out to our customer service team now! Many pop stars, among them Lady Gaga , have commissioned hats as publicity stunts. A helmet traditionally worn by British police constables while on foot patrol. Boost your brand with this custom beanie! This is a fluid situation and we will be monitoring and adjusting our operations as needed. -

Corps of Discovery Hats 20 What Did the Explorers Really Wear on Their Heads? by Bob Moore

Chinook Point Decision Columbia Gorge John Ordway White House Ceremony The Official Publication of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. May 2001 Volume 27, No. 2 C ORPS OF DISCOVERY HATS What did Lewis & Clark and their men really wear on their heads? ROW 4/C AD The Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. P.O. Box 3434, Great Falls, Montana 59403 Ph: 406-454-1234 or 1-888-701-3434 Fax: 406-771-9237 www.lewisandclark.org Mission Statement The mission of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. is to stimulate public appreciation of the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s contributions to America’s heritage and to support education, research, development, and preservation of the Lewis and Clark experience. Officers Active Past Presidents Directors at large President David Borlaug Beverly Hinds Cindy Orlando Washburn, North Dakota Sioux City, Iowa 1849 “C” St., N.W. Washington, DC 20240 Robert K. Doerk, Jr. James Holmberg Fort Benton, Montana Louisville, Kentucky President-Elect Barbara Kubik James R. Fazio Ron Laycock 10808 N.E. 27th Court Moscow, Idaho Benson, Minnesota Vancouver, WA 98686 Robert E. Gatten, Jr. Larry Epstein Vice-President Greensboro, North Carolina Cut Bank, Montana Jane Henley 1564 Heathrow Drive H. John Montague Dark Rain Thom Keswick, VA 22947 Portland, Oregon Bloomington, Indiana Secretary Clyde G. “Sid” Huggins Joe Mussulman Ludd Trozpek Covington, Louisiana Lolo, Montana 4141 Via Padova Claremont, CA 91711 Donald F. Nell Robert Shattuck Bozeman, Montana Grass Valley, California Treasurer Jerry Garrett James M. Peterson Jane SchmoyerWeber 10174 Sakura Drive Vermillion, South Dakota Great Falls, Montana St.