2005 Literary Review (No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to 2D-Animation Working Practice

Prelims-K52054.qxd 2/6/07 5:18 PM Page i Character Animation: 2D Skills for Better 3D This page intentionally left blank Prelims-K52054.qxd 2/6/07 5:18 PM Page iii Character Animation: 2D Skills for Better 3D Second edition Steve Roberts AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON • NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Prelims-K52054.qxd 2/6/07 5:18 PM Page iv This eBook does not include ancillary media that was packaged with the printed version of the book. Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA First published 2004 Second edition 2007 Copyright © 2007, Steve Roberts. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved The right of Steve Roberts to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone (ϩ44) (0) 1865 843830; fax (ϩ44) (0) 1865 853333; e-mail: [email protected]. Alternatively you can submit your request online by visiting the Elsevier web site at http://elsevier.com/locate/permissions, and selecting Obtaining permission to use Elsevier material Notice No responsibility is assumed by the publisher for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions or idead contained in the material herein. -

Nielsen Music 2017 Year End Music Report Canada

NIELSEN MUSIC 20I7 YEAR-END MUSIC REPORT CANADA 1 INTRODUCTION The music industry in Canada has never been stronger, with record consumption, growing live music attendance and a new class of emerging artists. Nielsen Music has also had an amazing, transformative year. Technological advancements and new partnerships have allowed us to provide robust, comprehensive data in more accessible, customizable and useful ways in 2017. Over the past year, we received a record number of requests for Nielsen Music research and insight reports. Welcome to the Nielsen Music Year-End Report, which examines the trends that shaped the Paul Shaver Canadian music industry in 2017 with definitive consumption figures and charts. Vice President/ Head of Nielsen Music Canada Overall consumption of albums, songs and On-Demand Audio streaming grew 13.6% year-over- year. On-Demand Audio streaming offset decreases in track and album sales and, on December 3, for the first time in history, it surpassed the 900 million per week mark. Ed Sheeran led all artists in Canada with overall consumption and had the top-selling album of the year. Six Canadians had No. 1 albums on the Billboard Canadian Albums chart in 2017, including The Weeknd’s Starboy, Drake’s More Life, Arcade Fire’s Everything Now, Shania Twain’s Now, Pierre Lapointe’s La Science Du Coeur and Gord Downie’s Introduce Yerself. The passing of Gord Downie captured the nation’s attention. In the week following his death, The Tragically Hip’s overall consumption increased by 1,000% over the previous week. Also, six of the group’s albums re-entered the Billboard Canadian Albums chart. -

Judge Jim Hely of Westfield Transit Village Review CONTINUED from PAGE 1 CONTINUED from PAGE 1 State Officials Are Present, “The Town Them,” Ms

Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus Published Every Thursday Since September 3, 1890 (908) 232-4407 USPS 680020 Thursday, July 23, 2009 OUR 119th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 30-2009 Periodical – Postage Paid at Westfield, N.J. www.goleader.com [email protected] SIXTY CENTS Despite Reports, Westfield Not Pursuing Transit Village Status By MICHAEL J. POLLACK hoods where people can live, shop, very quickly” and noted that a transit Specially Written for The Westfield Leader work and play without relying on village designation is “not front and WESTFIELD – Despite reports to automobiles.” Towns such as center” on the mayor or council’s the contrary, the Town of Westfield is Cranford, Morristown and South Or- agenda. not pursuing a Transit Village desig- ange are considered transit villages. Mayor Andy Skibitsky confirmed nation at present. Though it may study While reports of Downtown that the “impromptu” and “last- the “appropriateness” of such a des- Westfield Corporation (DWC) Ex- minute” meeting took place, but he ignation in the future, town officials ecutive Director Sherry Cronin lead- said there is “no directive to pursue refuted a report that said the town was ing the Transit Village Taskforce on a this…it will never happen without “eyeing” the matter seriously. tour of the town two Fridays ago are mayor and council approval.” According to the New Jersey De- accurate, Frank Arena, the Westfield While the mayor said there was partment of Transportation (DOT) Town Council’s DWC liaison, said it “nothing wrong” with meeting with website, the Transit Village initiative was an “impromptu” meeting. the taskforce, it is not something his creates incentives for municipalities Mr. -

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

Download, and I Was One at Once

A Real Artist in Residence Local family takes their decorations to the next level. by !Jacob Cottingham I In these cynical times, it seems as though abstractions like "the holiday spirit' are merely part of another ad jingle and not something one encounters often in day-to-day life - unless of course your days lead you past Kidd Lane and the beaming colors e'manating 10,000 watts of holiday spirit from the Coons family's yard. With nearly every Christmas decoration known to the Hudson Valley, the Coons have made their house, shed, and lawn into a Christmas spectacular that does more to slow drivers on Kidd lane than the Sheriff. The setup includes brilliantly lit wire frames in all manner of shapes, from bells to Mickey Mouse. The yard also contains a life-size animatron- 1c dancing Santa, changing spotlight projections of Christmas images onto the side of the house: a small train track; and a nativity scene equipped with a programmable LED strip that plays music. For three years I've lived on Montgomery St. and have had the opportunity to see the slow process of setting up and taking down the most impressive light display this side of Pink Floyd . The Coons family includes Joann, Joseph Sr., Joseph Jr., Catherine and Charissa. I baked some. cookies in Christmas shapes, and brought them over to discuss the lights with Joann. who guides each years final display. The tradition of lights began in 1988, with only two pi eces of seasonal decorations. Within the last ten years, the decorations have taken a turn towards a more grand scale. -

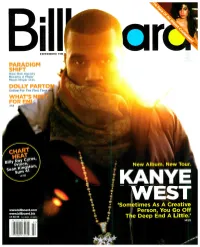

`Sometimes As a Creative

EXPERIENCE THE PARADIGM SHIFT How One Agency Became A Major Music Player >P.25 DOLLY PARTO Online For The First Tim WHAT'S FOR >P.8 New Album. New Tour. KANYE WEST `Sometimes As A Creative www.billboard.com Person, You Go Off www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK E5.50 The Deep End A Little.' >P.22 THE YEAR MARK ROHBON VERSION THE CRITICS AIE IAVIN! "HAVING PRODUCED AMY WINEHOUSE AND LILY ALLEN, MARK RONSON IS ON A REAL ROLL IN 2007. FEATURING GUEST VOCALISTS LIKE ALLEN, IN NOUS AND ROBBIE WILLIAMS, THE WHOLE THING PLAYS LIKE THE ULTIMATE HIPSTER PARTY MIXTAPE. BEST OF ALL? `STOP ME,' THE MOST SOULFUL RAVE SINCE GNARLS BARKLEY'S `CRAZY." PEOPLE MAGAZINE "RONSON JOYOUSLY TWISTS POPULAR TUNES BY EVERYONE FROM RA TO COLDPLAY TO BRITNEY SPEARS, AND - WHAT DO YOU KNOW! - IT TURNS OUT TO BE THE MONSTER JAM OF THE SEASON! REGARDLESS OF WHO'S OH THE MIC, VERSION SUCCEEDS. GRADE A" ENT 431,11:1;14I WEEKLY "THE EMERGING RONSON SOUND IS MOTOWN MEETS HIP -HOP MEETS RETRO BRIT -POP. IN BRITAIN, `STOP ME,' THE COVER OF THE SMITHS' `STOP ME IF YOU THINK YOU'VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE,' IS # 1 AND THE ALBUM SOARED TO #2! COULD THIS ROCK STAR DJ ACTUALLY BECOME A ROCK STAR ?" NEW YORK TIMES "RONSON UNITES TWO ANTITHETICAL WORLDS - RECENT AND CLASSIC BRITPOP WITH VINTAGE AMERICAN R &B. LILY ALLEN, AMY WINEHOUSE, ROBBIE WILLIAMS COVER KAISER CHIEFS, COLDPLAY, AND THE SMITHS OVER BLARING HORNS, AND ORGANIC BEATS. SHARP ARRANGING SKILLS AND SUITABLY ANGULAR PERFORMANCES! * * * *" SPIN THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR SUMMER! THE . -

Two Kinds of Trouble

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2011 Two Kinds Of Trouble Rebecca Minnich CUNY City College of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/507 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Two Kinds Of Trouble A Novel by Rebecca Minnich March 16th, 2011 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the requirements for a degree of Master of Fine Arts of the City College of New York 1 Table of Contents Two Kinds Of Trouble……………………………………………………….1-419 2 August, 10, 1977 – Madison, Wisconsin Chapter One “Does he have to move out? Can’t you make up? Are you sure? Did you try?” These are the questions Patty asked her mother. “Sweetie, yes. And I don’t expect you to understand. It’s just the way it has to be,” said Gloria. Her voice was cracking, her glasses fogging behind the wet dish towel in her hand, wrapped around red knuckles, rubbing a plate dry. “It’s all our fault,” said Patty’s brother, David, who was leaning over the back of a chair with his head in his hands like he was on a soap opera. “If we hadn’t been such rotten kids, this wouldn’t have happened.” Patty looked at David to see if he was serious. God, he was. -

Entire Songlist

APA Mobile Disco 1300 723 555 Songlist - All June 2003 title artist - 06 - It Is A Fire Portishead "family affair." mary j. blige. "Judy"(hooked on coke) ice jupiter groove (05)Fragma - Every Time You Need Me (Pulse Driver Remix) Various Artists (alabama_with_n'sync)-god_myust_have_spent_a_little_more_time_on_you (B.Z. feat Joanne) - Jackie (beatles) twist and shout (brooks_&_dunn)-missing_you artist (dixie_chicks)-ready_to_run artist (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Britney Spears (Kenny Loggins) Foot loose (Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley (toybox)-the Sailor Song (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson (Your Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears ...Bobyahead! Tag team ...Is calling sm trax [Silence] Dixie Chicks [Your Drive Me] Crazy Britney Spears 001 I-O 01 - Across The Night Silverchair 01-50 Cent In The Club Dirty-cms 01-i Saw Her Standing There Beatles 01-ja_rule_feat._cadillac_tah_ aint_that_funny_(main-ego 02 02 - Simple Creed Live 03 03 - MARTINA McBRIDE I LOVE YOU RUNAWAYBRIDE - MUSIC 03 - Somethin stupid Robbie Williams 04 - Homeworld 04 - I Try Macy Gray 041 James - Laid 04-ll Cool J-paradise Ft Amerie 04-ll_cool_j-paradise_ft_ameri 05 05 - Bug A Boo DESTINY'S CHILD 05 - S Club 7-Bring It All Back NOW 43 05 - SMOOTH FEATURING ROB THOMAS SANTANA-SUPERNATURAL 05 Stimulant DJ's - Kickin' da Hard House Anthems 3 06 07 07 - Crush Mandy Moore 08 09 09 Promises My-Albums.com Billie Piper 1 - Korn 1 - Bad Moon Arisen Creedance Clearwater Revival 1 - Hallowed Point 1 - Hell Awaits Slayer 1 - Suzie Q Creedance Clearwater Revival -

Cities Full of Symbols: a Theory of Urban Space and Culture (AUP

Cities ful of Symbols Boek 2_Layout 2 21-10-11 12:10 Pagina 1 Cities Full of Symbols Cities ful of Symbols Boek 2_Layout 2 21-10-11 12:10 Pagina 2 Cities Full of Symbols A Theory of Urban Space and Culture Cities ful of Symbols Boek 2_Layout 2 21-10-11 12:10 Pagina 3 Edited by Peter J.M. Nas Leiden University Press Cities ful of Symbols Boek 2_Layout 2 21-10-11 12:10 Pagina 4 4 Cities Full of Symbols This book is published in print and online through the online OAPEN library (www.oapen.org). OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic research by aggregating peer reviewed Open Access publications from across Europe. Cover design and lay-out: Mulder van Meurs, Amsterdam ISBN 978 90 8964 125 0 e-ISBN 978 94 0060 044 7 NUR 648 / 758 © P.J.M. Nas / Leiden University Press, 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. -

Case 15-10104-LSS Doc 309 Filed 04/08/15 Page 1 of 98

Case 15-10104-LSS Doc 309 Filed 04/08/15 Page 1 of 98 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 HIPCRICKET, INC.,1 Case No. 15-10104 (LSS) Debtor. AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA } } ss.: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES } DARLEEN SAHAGUN, being duly sworn, deposes and says: 1. I am employed by Rust Consulting/Omni Bankruptcy, located at 5955 DeSoto Avenue, Suite 100, Woodland Hills, CA 91367. I am over the age of eighteen years and am not a party to the above-captioned action. 2. On April 3, 2015, I caused to be served the: a) Notice of (I) Conditional Approval of the Amended Disclosure Statement; (II) Hearing to Consider Confirmation of the Plan; (III) Deadline for Filing Objections to Confirmation of the Plan; (IV) Deadline for Voting on the Plan; and (V) Bar Date for Filing Administrative Claims Established by the Plan, (the “Notice”), b) Amended Plan of Reorganization of the Debtor Dated March 31, 2015 [Docket No. 293], c) Amended Disclosure Statement for the Plan of Reorganization of Hipcricket, Inc. [Docket No. 294], d) Committee Plan Support Letter (re: Recommendation of Creditors’ Committee in Favor of Chapter 11 Plan of Reorganization), (2a through 2d collectively referred to as the “Solicitation Package”) e) Class 3 General Unsecured Claims Ballot to Accept or Reject Chapter 11 Plan of Reorganization (the “Class 3 Ballot”), 1 The last four digits of the Debtor’s tax identification number are 2076. The location of the Debtor’s headquarters and the service address for the Debtor is 110 110th Avenue NE. -

26°C—36°C Today D

Community Community Majlis-Frogh- WCM-Q e-Urdu Adab professor P6is going P16 scales the to present its 21st French Alps with seven Aalmi Awards this of his cancer patients to Thursday at Katara’s help them rebuild trust Amphitheatre. in their bodies. Tuesday, October 31, 2017 Safar 11, 1439 AH DOHA 26°C—36°C TODAY LIFESTYLE/HOROSCOPE 11 PUZZLES 12 & 13 To the fore Young journalists COVER bring the reality of STORY favelas to the rest of Brazil. P4-5 HARD LIFE: The back alleys and pathways that wind through the Rocinha favela have stories to tell and these are finding space in the free newspaper Fala Roca. 2 GULF TIMES Tuesday, October 31, 2017 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT Arts Fest WHERE: Schools in Doha WHEN: Nov 9, 10, 11 Frends Cultural Centre is organising its School Arts Fest for Qatar-based Malayalee students. More than 4,000 students are expected to participate in the programme to be held in different schools. Competitions are being organised in five categories: Kids, Sub Junior, Junior, Pre-Senior, and Senior. For further details, please call 6678 7007, 5586 7913, or 5553 6801. EVENTS PRAYER TIME Championship is sure to be an exciting and unpredictable last round. This Cultural Diversity Festival Fajr 4.23am Halloween year the event will be from Thursday to WHEN: Until Nov 11 Shorooq (sunrise) 5.41am WHERE: Fraser Suites West Bay Saturday. WHERE: Katara Zuhr (noon) 11.17am WHEN: Until Today TIME: 7:30 pm - 9:30 pm Asr (afternoon) 2.30pm TIME: All Day ISC Skipping Rope Open Cultural Village Foundation- Maghreb (sunset) 4.57pm Pumpkin season is in the air as the Championship Katara in co-operation with UNESCO Isha (night) 6.26pm ghosts and goblins plan to descend to WHERE: Birla Public School Office in Doha is hosting a Cultural Fraser Suites West Bay, Doha to play WHEN: Nov 3 Diversity Festival on its premises ‘trick or treat’ this Halloween.